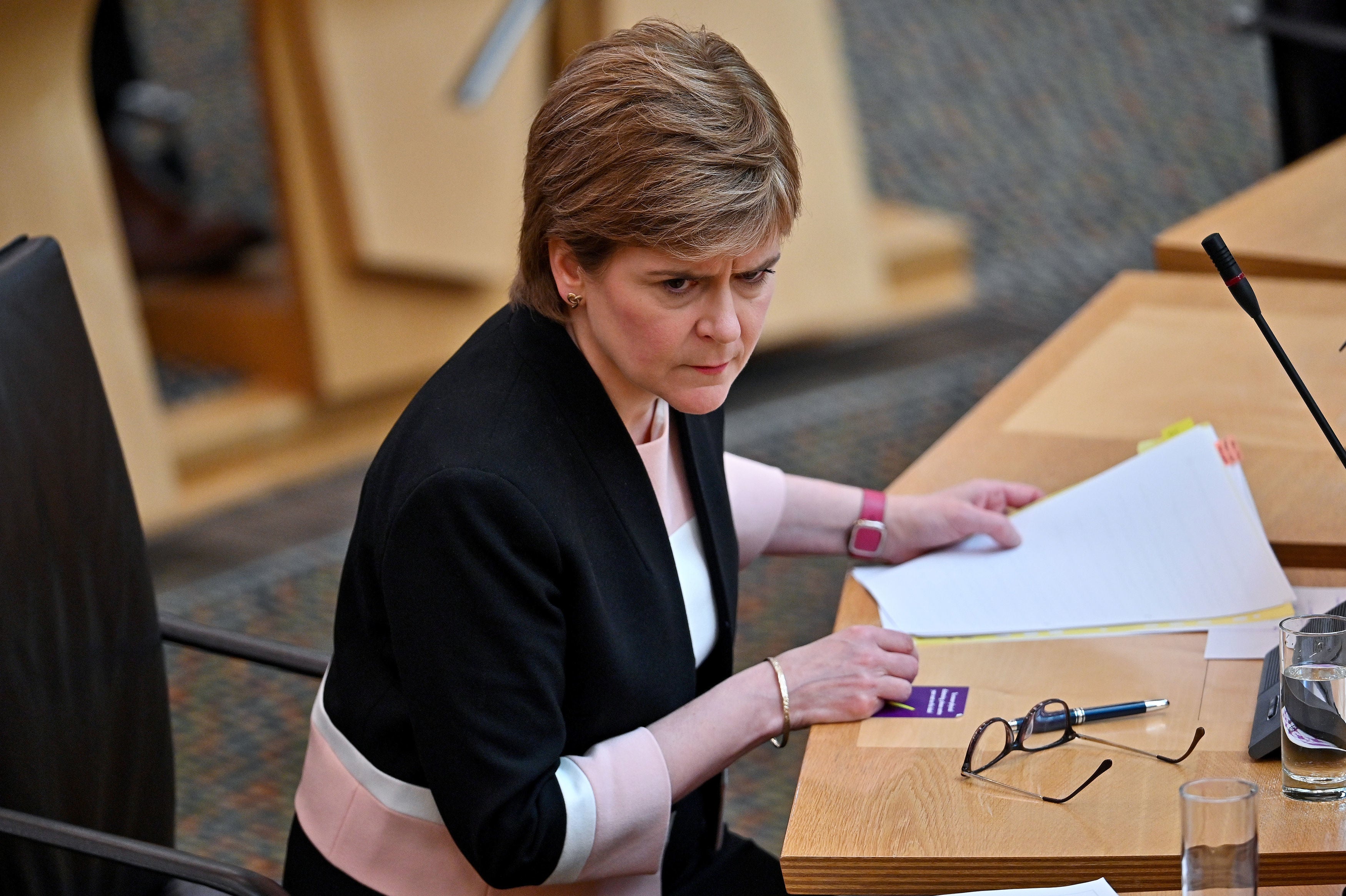

Where is Nicola Sturgeon? The first minister’s absence raises questions about Scottish independence

What a difference a year makes. Twelve months ago, the Scottish National Party was riding high, writes Mary Dejevsky

It stands to reason that to be “newsworthy”, something has to happen. But there are times when something not happening may be at least as significant – if not more so.

I offer you the current nigh-invisibility of Scotland’s first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, and the near-silence of those advocating Scottish independence. What a difference a year makes. Twelve months ago, the Scottish National Party was riding high. The result of the EU referendum was still fuelling calls for independence, given extra force by Boris Johnson having “got Brexit done”. If Scotland wanted a future in the EU, it would have to leave the UK.

This, in turn, lent additional import to the 2021 Scottish parliamentary elections. This time last year, Sturgeon was already eyeing an overall SNP majority as a mandate for a new independence referendum. That Johnson took a dim view of such a referendum only made the cause more attractive to rebellious Scots.

And then there was the pandemic. Nicola Sturgeon was making daily appearances at her own coronavirus briefings, looking and sounding very much in charge. Her instructions to Scots seemed precise and assured, especially when viewed south of the border. They were also often ahead of measures announced for England, making the Scottish government look at once more competent and more farsighted.

It was already too late to ask how sensible it had actually been to make health a devolved responsibility, given the propensity of infections to cross borders. But the pluses of devolution for the Scottish first minister – at that time, at least – were clear.

Scotland’s Covid deaths per capita were running behind those for the rest of the UK, and some of that was put down to the decisiveness shown by Sturgeon. She became an example to follow. What is more, Scotland’s record – seen as superior to England’s – could also be seen, and not just by those who were already inclined to do so, as a vindication of Scotland’s independence aspirations. It was behaving as a country in its own right, using the powers at its disposal, and demonstrating that independence could be more than a romantic dream; it could work.

And maybe it could, and still can. But between then and now a lot has changed, including, crucially, the balance of advantage. Wisely, no one is boasting about it in Westminster, but the fact is that a lot of the dynamism seems to have gone out of the independence cause. The tide of Scottish nationalism seems for the first time in a long while to be in quite serious retreat. As a force with the capacity to destroy the union, it looks spent.

Some evidence comes from opinion polls. A poll last month (for The Sunday Times) showed support for independence at 45 per cent, down 4 per cent from April, with support for the union at 48 per cent, and 7 per cent “don’t knows”. This contrasts with polls through last summer and winter, which showed support for independence consistently ahead of support for the union and at times passing 50 per cent. The decline set in last spring, extended through the May elections, when the SNP fell just short of an overall majority, and has continued since.

Further evidence comes from The Scotsman – alright, a pro-union newspaper – which confirmed, via a Freedom of Information request, that the Scottish government has done no work whatever on a new independence referendum since the pandemic hit. Now this may indeed be, as SNP officials responded, that there had never been any intention to address the referendum issue until the pandemic was over. But to have done absolutely nothing to advance what was the central proposition of the SNP’s election campaign suggests at very least that the new government has felt under no pressure even to keep up appearances on this score.

But the most compelling evidence of all is the current low profile assumed by Nicola Sturgeon – to the point where there have been rumours that she might leave Scottish politics altogether and seek a new position in the EU.

Now, it could be that, post-pandemic, the constitutional issue bounces back. Whether support for independence will also bounce back to last year’s levels, however, is a separate question. For all Sturgeon’s insistence that she wants a new referendum by the end of 2023, it would not make a lot of sense for her to press for another vote if the polls point unambiguously to defeat – as well they might, because the tables as between Scotland and the UK, between Sturgeon and Boris Johnson, have been turning.

The question is why. One obvious reason is that Scotland’s Covid record has been losing its gloss, and given that success in the early stages of the pandemic was associated so closely with the first minister, failures are bound to rub off on her too. That includes the death rate in Scotland’s care homes, for instance, which now exceeds that in England, and Scotland’s failure to meet its targets for vaccination. Westminster has been notably cooperative in ensuring vaccine supplies to the devolved nations, making it even harder for Scotland to pass the blame on to London.

A second reason, seen not only with vaccine supplies, is that London has become savvier in handling the devolved nations. In flags and in “branding” the union now has a more marked presence in Scotland than it did even a year ago. London now seems to have decided that too much – in symbolism at least – was ceded to Edinburgh, leaving the impression, perhaps, that it had given up on the union without a fight. That is no longer so.

A third reason – and how far London’s hand may be discerned behind some of this may never be known – is that Sturgeon’s Scotland and the SNP’s record is suddenly being subject to more critical scrutiny south of the border, with the result that it no longer seems the superior model it might once have done. Drug deaths in Scottish cities? Higher than Newcastle or Liverpool. Deaths among homeless people? Same dismal record, and rising. Homelessness overall? Not so good. The much-vaunted welcome for migrants, well, not so fast.

And a fourth reason reflects Nicola Sturgeon’s own political difficulties at the head of what has become, as the years have gone by, an increasingly incestuous political clan. The result so far is a schism between Sturgeon and the “big beast” of Scottish nationalsm, Alex Salmond; a nasty internal party dispute aired at public hearings; a court triumph for Salmond over sexual harassment charges, and the SNP facing an upstart Alba party that could yet gather just enough support to nip at the SNP’s dominance.

All these SNP problems may have come about by themselves – a product of too little challenge over the years. They may also, and I only hazard this, have received a little push from London. But the longer-term consequence could well be that Boris Johnson, with his vaunted luck, and Michael Gove, with his understanding of Scotland, have together seen off Scottish separatism and be ready to countenance a more genuinely federal arrangement that could also benefit Wales.

Northern Ireland, on the other hand, may be another story. While independence for Scotland always threatened huge complications, from a new land border to the transfer of naval and nuclear facilities, any move towards a united Ireland could simplify things, leaving the equation as between separation and the union more finely balanced. If more efforts than meet the eye are being made by London to keep Scotland in the union, it would be no surprise to learn that with Northern Ireland, fine words far outnumber the deeds.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments