How ministers’ panic over terror could make the situation worse

The government says keeping terrorists in jail will make the public safer, but the evidence calls that claim into question, Lizzie Dearden writes

Next week, MPs are to consider “emergency legislation” that aims to keep terror offenders who were due to be automatically released in prison for longer.

The proposals – which lawyers say may violate the European Convention on Human Rights – were announced a day after the Streatham terror attack.

It was the third knife rampage in just over two months to be launched by a convicted terror offender, following the Fishmongers’ Hall attack and a stabbing by two inmates inside a high-security jail.

The three incidents have come in rapid succession, after more than two years of relative peace after the spate of atrocities that hit the UK in 2017.

Those attacks were largely perpetrated by terrorists who were either completely unknown to the security services, or judged to be a far lesser risk than they were because of intelligence gaps.

This time, the government has no such excuse. These three attacks have been committed by men convicted of previous terror offences.

While Usman Khan apparently gave the appearance of reform, Brusthom Ziamani was known for his rampant extremism when he allegedly attacked prison officers while wearing a fake suicide vest in HMP Whitemoor.

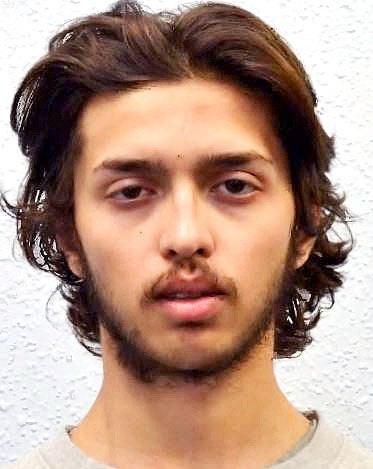

Sudesh Amman was being followed by undercover police – because of intelligence he wanted to conduct an attack – but was able to launch one anyway.

It is not a reassuring picture, and the government has reacted quickly with a deluge of policy proposals.

The first, reacting to the Fishmongers’ Hall attack, came in January. Lie detector tests and laws to end the automatic early release of future terror convicts were proposed.

After the Streatham attack, the “emergency legislation” was announced that would go further by ending the early release of offenders who were sentenced under the old regime.

The change affects around 50 current prisoners, whose lawyers are already threatening legal challenges.

According to calculations by the Henry Jackson Society, the next terrorist – Isis supporter Mohammed Zahir Khan – is due to be released from prison on 28 February.

The deadline has provoked headlines describing a “race against time” for the government to pass its proposed law before he can be freed.

The sense of urgency is convenient for ministers wanting to push their plans through parliament at high speed.

It can be difficult for MPs to question any terror laws without being accused of disregarding public safety or even favouring extremists.

Proper scrutiny becomes even more difficult in an atmosphere of panic over a succession of terror attacks, and the forthcoming release of more potentially dangerous extremists.

But that should not stop vital questions being asked. For example, why is the legislation being introduced as an “emergency law”.

The issue was not deemed an emergency a fortnight ago when the government announced a raft of other terror laws, or indeed last year when it created other new powers in the controversial Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Act.

And all signs point to the real emergency not being the timing of terrorists’ release, but what is happening to them in prison

Sudesh Amman is not known to have undergone deradicalisation work, and Usman Khan appears to have deceived his mentors and probation officers.

Concerns over Islamist radicalisation inside British jails has been mounting for years, to the point that judges are now sentencing terror offenders on the basis that jailing them could actually make them more of a threat.

The Parole Board itself has warned that jailing low-level extremists can “result in them becoming more likely to commit terrorist acts when they are released”.

A government-commissioned review in 2015 prompted the creation of three separation centres for terrorists who radicalise other prisoners, but only one is in use.

There has been no attempt to prove that keeping terrorists in jail for longer will reduce the chance of attacks, and that jihadis like Amman would not simply enact their desires at the later point of release.

But in its myriad proposals, Boris Johnson’s government has not proposed any assessment of radicalisation or rehabilitation work inside prisons.

Instead, it is blindly pushing to keep terrorists inside for longer without any evidence that they will emerge as less of a threat to the public.

The government clearly feels it needs to be seen doing something. We must all hope that it’s not the wrong thing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments