This jobs package shows the Conservatives have learnt a lesson from history – but it still might not be enough

The chancellor signalled that there could be more fiscal support to come for the UK in the Autumn Budget – but by then unemployment could be soaring back up to those dreaded 1980s levels, says Ben Chu

Since the days of Margaret Thatcher, the image of the Conservatives in many parts of the country has been of a party that doesn’t care that much about mass unemployment – or at least cares about other things more.

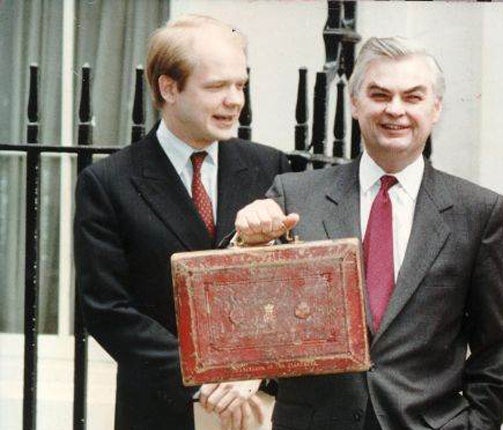

That order of priorities seemed to be summed up by former chancellor Norman Lamont who told the House of Commons in 1991 that high unemployment in a previous recession had been a “price worth paying” for bringing down stubborn inflation.

It’s true that under David Cameron and George Osborne unemployment plunged to its lowest levels since the 1970s, something they frequently hailed as a “jobs miracle”.

In recent years the Conservatives have even taken to promising “full employment”, but this pandemic and the brutal economic impact of the lockdown has put the new Tory enthusiasm for jobs to the test.

Rishi Sunak rose to the occasion in his Summer Statement – rhetorically at least.

The chancellor’s promise that he will “never accept unemployment as an unavoidable outcome” was probably crafted with the words of Lamont and Thatcher-era Conservative ministers in mind.

With forecasts flying around that UK joblessness could soar to the heights last seen in the early 1980s – touching the historically resonant three million mark – that was not only well-judged but necessary.

Yet what of the substance? First, praise where it’s due. The £2bn funding for a “kickstart” scheme of state-funded work placements for young people on benefits is significant.

This is essentially a resurrection of the Future Jobs Fund, introduced in the wake of the financial crisis by Labour. This was cancelled by the Coalition in 2010, with David Cameron claiming it “did not work”.

Studies subsequently showed it had, in fact, been effective. The programme’s comeback is welcome evidence that Conservatives, guided no doubt by those in the Treasury with an institutional memory, are capable of learning from history.

And then there’s £1.6bn for increasing job centre staffing and vocational training. This kind of spending does not tend to capture headlines but is, nevertheless, extremely important in keeping the labour market running through a jobs recession.

The most expensive measure, though, is the £1,000 grant available to firms for every employee they bring back from furlough – something that could cost up to £9bn, depending on take-up.

It seems inevitable that many firms will be claiming this grant for workers who would have come back in any case. It might well have been better to have targeted that support at especially hard-hit sectors, such as hotels and restaurants.

The chancellor did, though, try to focus support on hospitality through a VAT cut (from 20 per cent to 5 per cent) for the hospitality sector and also a “Eat out to Help Out” meal subsidy scheme.

The hope here is that cheaper menu prices and the promise of a discount for diners will get these firms “bustling” with customers again, encouraging them to hire and retain waiting and catering staff.

It could help. Many of the better-off will have saved money in the lockdown and have the ability to spend more. And sensible think tanks such as the Centre for Cities and the Resolution Foundation have proposed time-limited spending vouchers to encourage consumption in these times of rampant uncertainty.

Yet the problem is that even cheaper prices might not lure people out if they remain concerned about the possibility of infection.

The data shows the UK is not as on top of the disease as many other countries. Stimulus could be in vain if the easing of the lockdown was premature, as the Oxford economist Simon Wren-Lewis has pointed out.

The cost of the overall stimulus package – put at up to £30bn by the Treasury – is not negligible, at around 1.5 per cent of GDP. That’s certainly big enough to help support activity – and of course, comes on top of the £160bn or so of support already implemented

Yet the discretionary boost could have been bigger. Germany and Japan have enacted larger fiscal packages relative to the size of their economies. And the United States is considering a new programme worth 15 per cent of GDP.

The chancellor signalled that there might be more fiscal support to come for the UK in the Autumn Budget. But by then many more businesses will already have made their staffing decisions as the furlough scheme is unwound and unemployment could be soaring back up to those dreaded 1980s levels.

Mr Sunak might end up wishing that he had gone all-in with his economic and jobs stimulus package sooner.

Another lesson of history is that, in recessions, the damage done by acting too late is often greater than what’s done by acting too early.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments