Are public sector workers getting a pay rise or not?

The government has heralded a pay rise for public sector workers, but unions warn more cuts are on the way. What’s really going on? Ben Chu looks at the numbers

The government announced on Monday night that some 900,000 public sector workers will receive a pay rise this year.

The Chancellor Rishi Sunak suggested this was a recognition of the immensely valuable job these workers had done in the pandemic.

“These past months have underlined what we always knew – that our public sector workers make a vital contribution to our country and that we can rely on them when we need them,” he said.

Yet it soon emerged that the new pay increases were not being accompanied with more money from the Treasury to government departments to enable them to pay them.

And Labour pointed out that the pay rise would still leave the average pay of many public sector workers below where it was a decade ago when adjusted for inflation.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday morning, the chancellor wrote a letter in which he spoke of the need for “restraint in future public sector pay awards”.

So what’s really going on? Is the pay of public sector workers actually going up or not?

What determines pay in the public sector?

The government appoints independent Pay Review Bodies to cover various public sector professions, such as teachers, police, nurses and members of the armed services and so on. These bodies are made up of civil servants and experts, some with direct knowledge of the profession.

Their job is to gauge labour market conditions, talk to unions and department officials, and to make a recommendation over how much pay should increase by for workers in that sector.

This is supposed to be based on the need to fairly compensate employees and also to facilitate recruitment and retention.

Ministers then decide whether or not to accept those recommendations.

This week’s announcement is essentially that the government has accepted the headline recommended rise for each workforce from their respective pay review bodies for 2020-21 and pledged to enact them.

So the pay of teachers will rise by 3.1 per cent, doctors’ by 2.8 per cent, prison officers’ by 2.5 per cent and so on.

This would be more than the expected rate of inflation for this year and next year, meaning this will be a real terms increase in pay.

However, the new pay announcements do not cover all of the 5.5 million public sector workers.

Nurses’ pay, for instance, is being determined by a three-year deal agreed with unions in 2018.

Where will the money come from?

The government said that the money will come from existing departmental budgets.

This means these departments will not receive fresh funds from the Treasury to cover the increased staffing bill.

This has concerned some because, with the wage bill such a dominant part of departmental expenditure, it suggests other services could end up being curtailed in order to afford it.

This could make the work of those public sector employees harder. Think, hypothetically, of a prison officer required to look after more inmates, or a teacher given fewer resources to educate the same number of children.

But a pay rise surely still makes workers better off?

In the austerity programme introduced by the Coalition in 2010 and extended by the Conservative after 2015 public sector pay was frozen in cash terms. That meant it fell after adjusting for inflation. After 2013 pay increases were capped at 1 per cent a year, still often below the rate of inflation, meaning real terms cuts.

Labour and the unions point out that, due to these cuts, the pay of most public workers will remain lower in real terms than it was a decade ago even after this latest rise.

The Trade Union Congress calculates that nurses are more than £3,000 worse off today than they were in 2010 and ambulance drivers have £1,600 less.

By this benchmark public sector workers will be only a little less worse off, rather than better off, because of these pay rises.

But hasn’t everyone’s pay suffered in recent years?

There are 5.5 million public sector workers and 27.5 million in the private sector.

Average public sector pay in the first quarter of this year was £552 a week, down 3 per cent in real terms from its peak in the first quarter of 2010

Meanwhile, private sector pay at £534 a week is around 5 per cent down on its earlier peak back in 2008.

Private sector pay fell more steeply after the 2008-09 financial crisis than public sector pay.

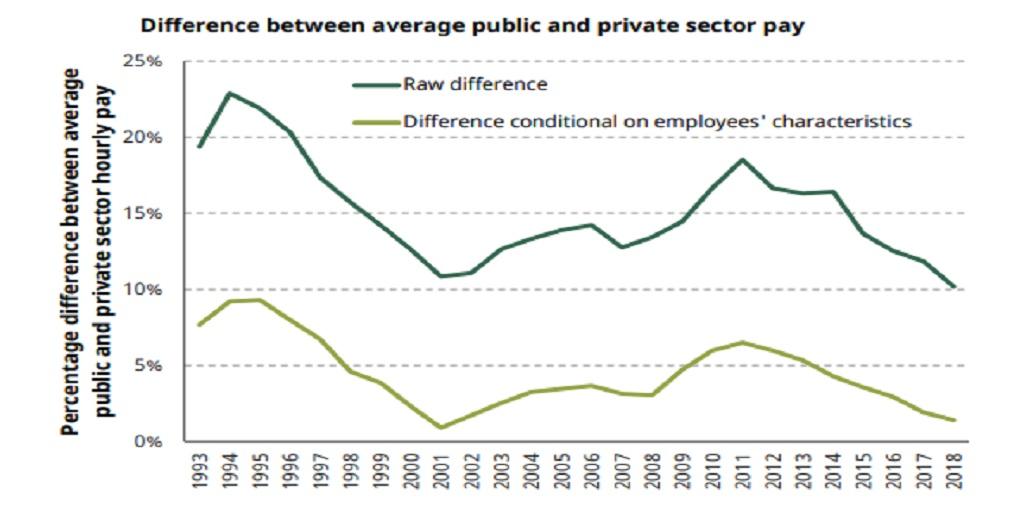

But since 2015 private sector pay has been increasing more rapidly. The differential between the two has considerably reduced.

Some analysts see that in itself as a justification for higher public sector pay. Because public sector workers, on average, have higher educational qualifications, skills and experience than private sector workers there should be a pay premium to reflect that. Otherwise retention and recruitment to public sector jobs will suffer.

What about future public sector pay settlements?

In his letter to Government departments on Tuesday setting up this Autumn’s three-year Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR), which will determine their budgets up to 2023-24, the Chancellor strongly hinted that, despite this year’s pay increase, there won’t be such increases in future years.

Mr Sunak noted that in May 2020 public sector pay was up by 3.7 per cent on the year before, compared to a fall of 1.2 per cent in the private sector, which he suggested means the divergence between average public and private sector pay is rising again. He also noted that the Office for Budget Responsibility is projecting a fall in average wages next year.

“For reasons of fairness, we must exercise restraint in future public sector pay awards, ensuring that across this year and the CSR period, public sector pay levels retain parity with the private sector,” he wrote.

This is a clear signal to departments not to budget for rising real public sector wages in the coming years.

“It’s hard to see how public sector workers can trust ministers after this cynical ploy to disguise plans for more pay restraint,” said Frances O’Grady of the TUC.

What does all this mean for public sector pay?

The wages of many public sector workers will indeed rise in real terms this year.

But, despite the rhetoric of the Chancellor about valuing public sector workers and the promises from the Prime Minister that the Government will not return to austerity, it’s also clear that they want to avoid giving the signal that there will be a sustained period of real terms public sector pay rises in the coming years.

And one cannot rule out more real terms cuts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments