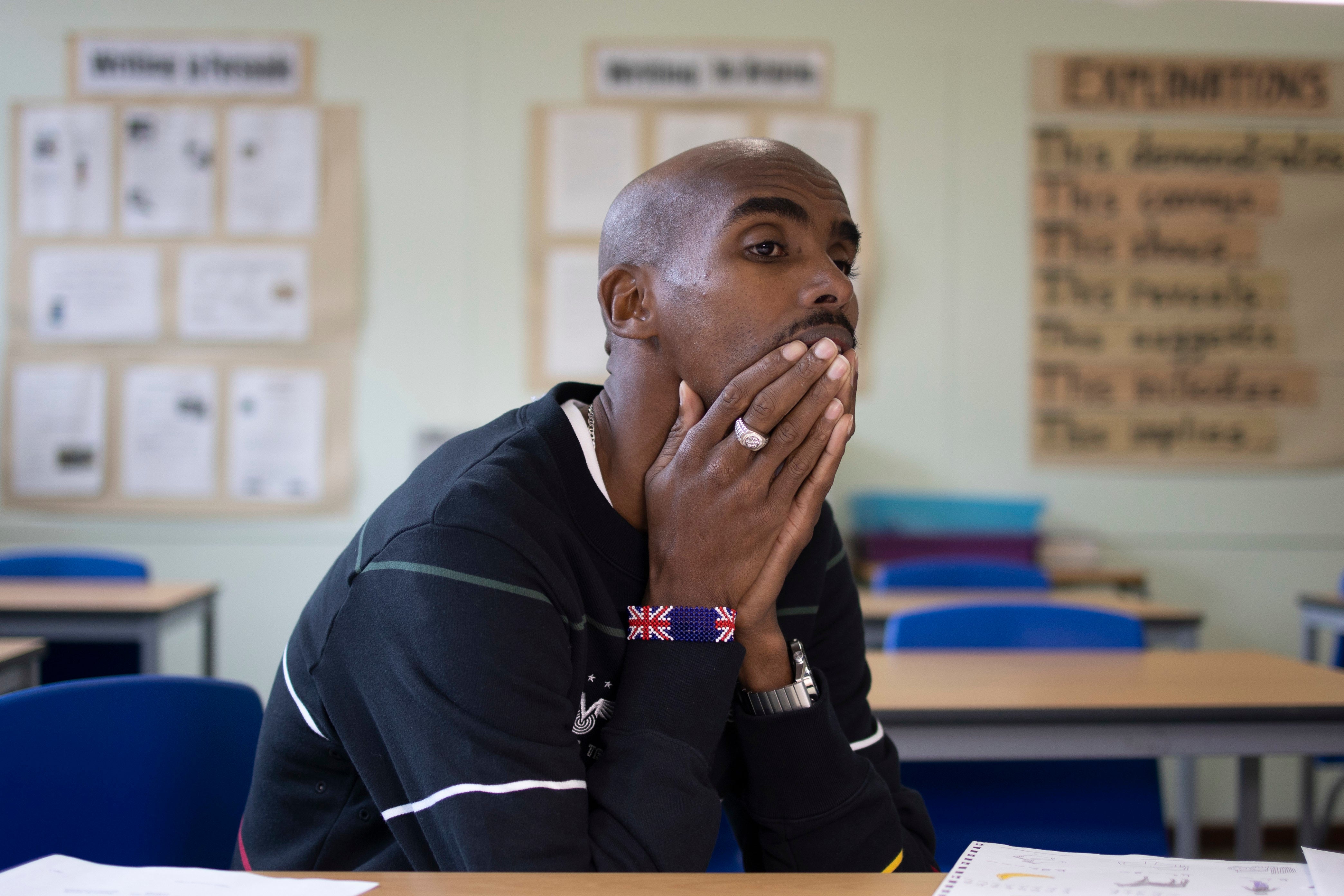

Mo Farah: What would happen to a trafficked child in the UK today?

Experts say there is a ‘state of precariousness’ for child victims navigating complicated immigration procedures, writes Lizzie Dearden

Sir Mo Farah’s decision to reveal that he was a victim of human trafficking as a child has sparked questions over how he would be treated if he arrived in the UK today.

The decorated Olympic athlete disclosed his experience as part of a BBC documentary, The Real Mo Farah, saying he had decided to tell his story “whatever the cost”.

The father of four, now 39, told how he was born in the unrecognised breakaway state of Somaliland as Hussein Abdi Kahin.

Sir Mo had previously said his parents brought him to the UK as a child, but revealed that his father was in fact killed in the civil war and he was separated from his mother.

At the age of nine, he was told he was going to Europe to live with relatives, and was initially excited.

But a woman he had never met then told him to say his name was Mohammed, and gave him fake travel documents showing his photo next to the name “Mohamed Farah”.

Sir Mo recalled going through a passport check in the UK using the fake documents, before being taken to a home in Hounslow, west London.

A piece of paper the child had carried with him with the details of a relative in Britain was ripped up and he was forced to work in domestic labour, caring for the family’s children.

Sir Mo was initially not allowed to attend school, but enrolled at a secondary school at the age of 12.

Teachers were told he was a refugee from Somalia but he eventually told his PE teacher, Alan Watkinson, the truth and moved to live with a friend’s mother.

Mr Watkinson applied for Sir Mo’s British citizenship, which he described as a “long process”, and in July 2000 he was recognised as a British citizen.

A Home Office spokesperson said it would be taking “no action whatsoever” against Sir Mo and that its guidance states that children are not considered complicit in “gaining citizenship by deception”.

The department denies treating Sir Mo differently because of his status, and says the same decision would be made for anyone in the same circumstances.

What has changed?

Immigration laws have undergone numerous changes in the three decades since Sir Mo arrived in Britain.

The current government has brought in a significant package of hardline laws in the Nationality and Borders Act, which seeks to make it easier to criminalise people reaching the UK irregularly and make it harder for them to stay in Britain.

Those laws are separate from the agreement to send asylum seekers deemed “inadmissible” to the British system because they have travelled through safe third countries to Rwanda.

The act puts new time limits on trafficking victims to provide the government with information supporting any claim for the protection needed to stay in the UK.

The Home Office believes that it grants most trafficked children leave to remain in the UK under a procedure designed for child asylum seekers.

UASC (unaccompanied asylum-seeking child) leave, which normally applies to under-18s who have been refused refugee status, grants leave to remain in the UK for 30 months or until they turn 17 and a half, whichever is shorter.

They must then apply for either an extension or, if they have legally become adults, another type of permission to stay in the UK.

Mary Atkinson, of the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, said: “If Sir Mo had been trafficked here today, it would likely take him months, if not years, longer to get the support he needed.

“Our government’s cold-hearted approach to immigration, including their new anti-refugee laws, also mean people are more likely to be exploited for years without speaking out. And when survivors do speak out, we know this government fails them again.

“Over the past few years our politicians have taken a wrecking ball to the ‘National Referral Mechanism’ – the pathway to protection for victims of trafficking – and many survivors now wait over a year in limbo before they get the protection they so desperately need.”

A Home Office spokesperson said: “We have clear systems for dealing with vulnerable children and since 2019 have helped thousands to rebuild their lives. In 2021 alone, 90 per cent of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children were granted leave at the initial decision stage.

“Any child identified as a potential victim of modern slavery or who seeks protection in the UK will have their case carefully considered and will be given the support they need.”

Would a child in Sir Mo’s position be sent to Rwanda?

No, a child at the age Sir Mo was when he arrived in the UK would not be considered for the scheme.

The main criterion is “inadmissibility” for consideration by Britain’s asylum system, but he did not apply for asylum.

If a trafficked child like Sir Mo did apply for asylum, they would still not be removed to Rwanda.

Because the policy targets Channel small boat crossings, one of the key grounds for inadmissibility is travelling through “safe third countries” like France, but Sir Mo flew directly from Djibouti during an ongoing conflict.

Laura Duran, a senior policy and research officer at anti-child trafficking network ECPAT, said: “If he was accepted as a child he wouldn’t be served an inadmissibility notice and he wouldn’t be liable for removal to Rwanda.

“The only children right now who would be liable for removal to Rwanda are those whose age is disputed. If his age is accepted as under 18 he wouldn’t be served that.”

What does happen to trafficked children?

Their treatment depends significantly on when they are recognised as victims of trafficking, and what proof they have.

Zoe Bantleman, legal director of the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association (ILPA), explained that many victims of trafficking – especially children – are not apprehended at the point they are brought into the UK and can “remain hidden” for years.

“Many victims of trafficking are undocumented in society and subjected to hostile environment measures,” she added.

“If he had been apprehended before obtaining British citizenship, and it was realised that he had not been granted legal status in the UK, he would need to navigate the UK’s complex asylum, humanitarian protection, modern slavery and immigration laws.

“Many people in such circumstances have no access to legal advice to help them leave their exploitative situation.”

The government plans to grant free legal advice to potential trafficking victims but several conditions must be met for access to that scheme.

“Crucially, to be recognised as a victim of trafficking, he would have been required to realise and process that he was a victim of trafficking, and be able to disclose traumatic events,” Ms Bantleman said.

“The Nationality and Borders Act will punish delayed disclosure, by requiring victims to disclose their trafficking experiences within a prescribed time frame or risk having their credibility damaged.

“It can take many years for victims of trafficking to be comfortable enough to disclose memories they are trying to forget. Even if he were recognised as a victim of trafficking, victims are often granted discretionary leave to remain for only short periods such as 12 or 30 months. Therefore, he could have remained in a state of precariousness.”

Can citizenship be removed from people using false documents?

Government guidance states that a person’s British nationality can be removed if they have given false information on their identity, “for example by using a false name”, or taking someone else’s identity – as Sir Mo was forced to.

But it adds: “If the person was a child at the time the fraud, false representation or concealment of material fact was perpetrated, the caseworker should assume that they were not complicit in any deception by their parent or guardian.”

Sir Mo was around the age of nine when he arrived in the country, and under the age of 18 when his application for British citizenship was granted.

But some experts claim that an adult in Sir Mo’s position could still find their citizenship at risk if they are “disbelieved” over their age or trafficking complaints.

What about modern slavery processes?

The National Referral Mechanism (NRM) is a framework for identifying and referring potential victims of modern slavery.

It is intended to protect people who are victims of human trafficking, slavery, servitude and forced or compulsory labour.

If the NRM confirms that someone is a victim of slavery – which it does in the vast majority of referrals for children – the government can choose to grant them discretionary leave to remain in the UK.

“Where the case involves a child the best interest of the child should always be factored into the consideration,” Home Office guidance states.

“In most cases, a standard period of up to 30 months discretionary leave will be appropriate.”

Ms Duran said that many children recognised as modern slavery victims are “siphoned into asylum procedures by local authorities”, which have a completely different legal threshold to succeed.

“They’re really complicated cases arguing they’re likely at risk of harm by being trafficked or abused, have to be fought in the tribunals, they can be 24, 25 and still in the appeal procedure,” she added.

“It deprives children of the opportunity for being normal teenagers.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments