Why has £50m funding failed to help grammar schools attract poor children?

Analysis: Schemes to diversify did not see meaningful changes in applications this year, writes Eleanor Busby

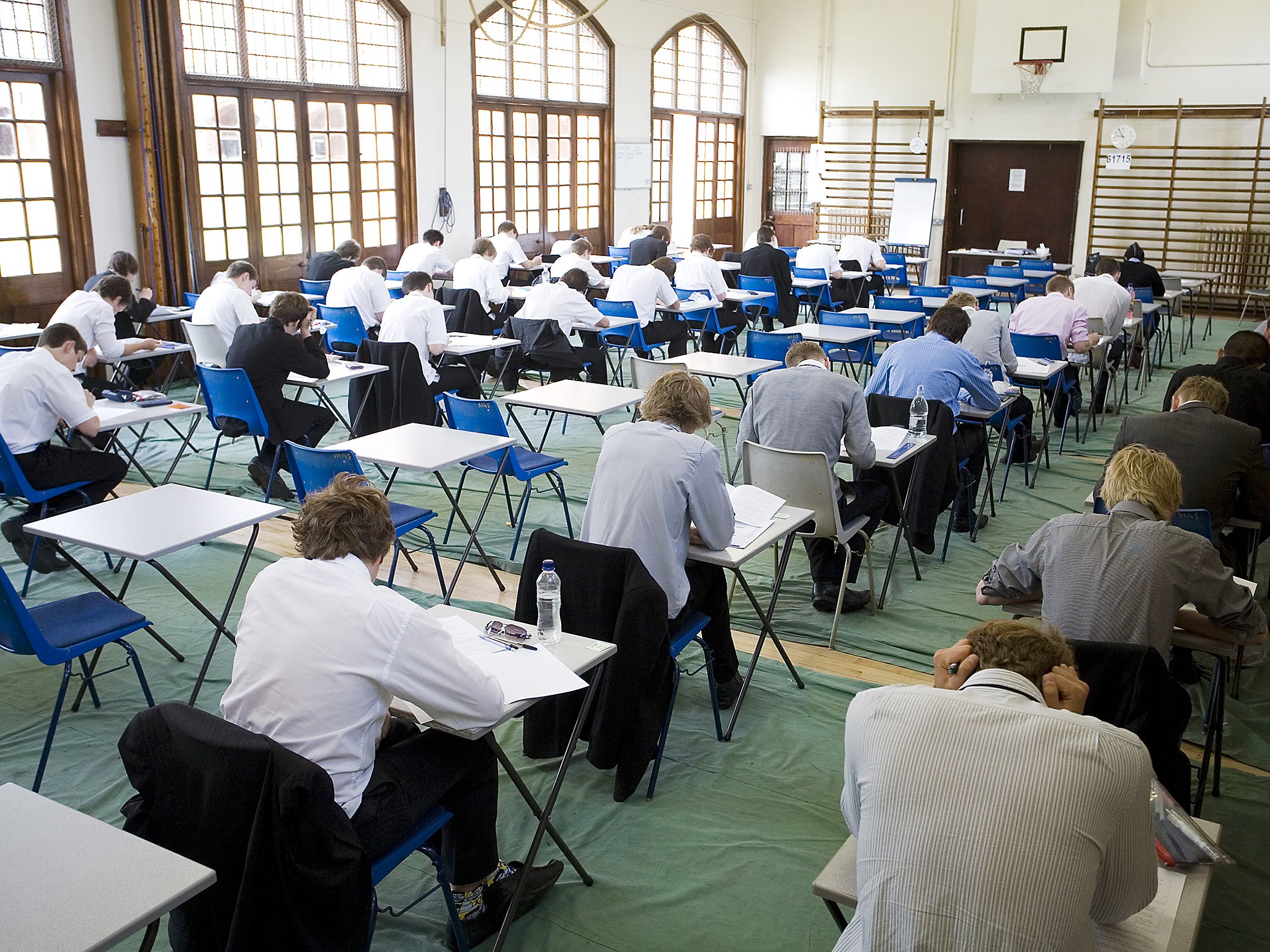

The grammar schools that remain in England have been widely viewed as bastions of privilege. These selective schools predominantly serve middle-class families who can afford tutoring, critics say.

A row about academic selection and social mobility has dominated education ever since Theresa May announced plans to open more grammar schools when she became prime minister in 2016.

Despite evidence to suggest the existing 163 selective state schools lack diverse intakes – around 2.6 per cent of grammar school pupils are on free school meals, compared to 14.1 per cent across all school types – the government still controversially awarded £50m to these schools to widen access.

Now figures obtained by The Independent reveal only 22 more pupils from poorer backgrounds sat the 11-plus exam in these schools in September, compared to the year before, despite extra funding.

The 16 selective state schools awarded a share of the expansion fund were all chosen based on their plans to diversify intakes through altered admission policies and increased outreach work.

However, they are still struggling to attract large numbers of pupil premium children – those who have received free schools meals – to apply to grammar schools. So why could this be?

Successful outreach work by selective schools often relies on good partnerships with primary schools that serve disadvantaged pupils. Poorer families are unlikely to apply to a grammar school if they do not think it is an option for their child.

The application process for grammar schools is also much earlier on in the school calendar so families who have not been made aware of these deadlines could miss out on the admission tests.

Less affluent families are also more likely to be put off by the private tutoring industry linked to the 11-plus exam for grammar schools, as they simply cannot afford the extra preparation.

And for some parents, the strict uniforms and old-fashioned buildings associated with many historic grammar schools, where pupils travel epic distances daily to get there, can be too alien to them.

Headteachers also say children on free school meals are less likely to achieve top results in Sats exams at primary school, which narrows the pool of candidates to target with outreach work.

The latest figures do not suggest a promising start to the government’s flagship policy to boost social mobility, but it may well be too early to judge whether it has been a complete failure. The funding only became available to the schools halfway through the last academic year.

For many years, grammar schools have been dominated by affluent families and that is not going to change overnight. But the spotlight must remain on existing grammar schools and their efforts to widen access – especially if the £50m a year expansion fund continues.

It will take more than a “pledge” to diversify intakes to overhaul a system that favours privilege.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments