How Crossrail delays risk holding up other vital infrastructure

Besides the short-term detriment the delay has caused, a bigger danger is that future projects will be scuppered by scepticism, writes Simon Calder

In the European league table of vast and really bungled infrastructure projects in a capital city, London lags way behind Amsterdam and Berlin.

To build an underground railway in what is basically a large marsh, you would probably call in the Dutch. But perhaps not the same bunch of engineers who were put to work on the North-South Metro line at the tail end of the 20th century.

The trains finally started rumbling beneath Amsterdam last year, 11 years late and after more than twice the original budget had been spent – working out at £3,000 per citizen.

Across in the German capital, the whispers are that the grandly titled Willy Brandt Airport Berlin Brandenburg will not, after all, open as promised in 2020 – and, like London’s Crossrail, may be delayed until 2021.

But Berlin’s cunning plan to consolidate the city’s air traffic in a single site in the old East Germany is a scheme that was due to open in 2011 – making it a full decade behind schedule.

By comparison, London’s Crossrail is a model project. It will probably be no more than three years late and one-third over budget.

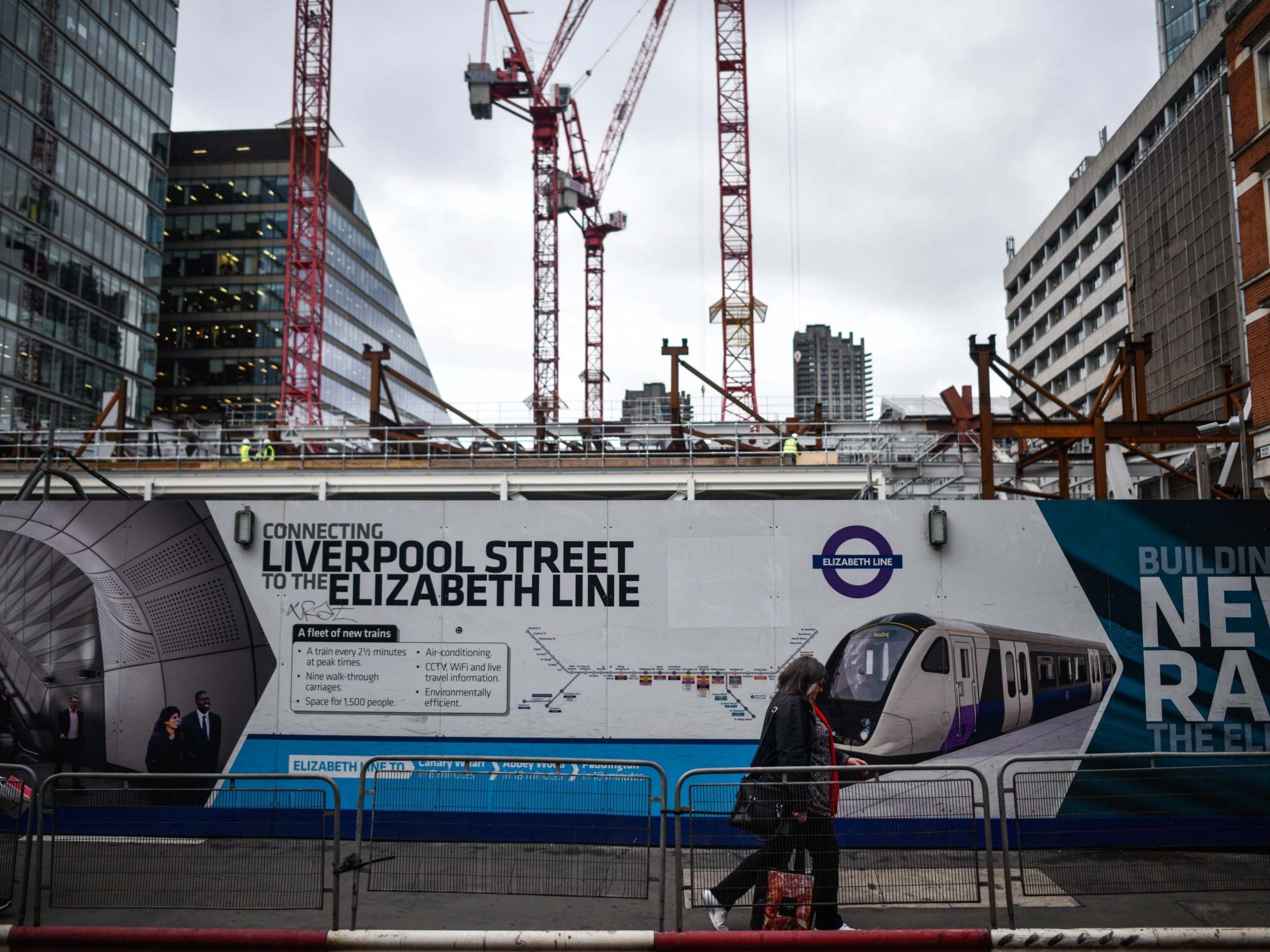

Yet taxpayers and travellers are rightly cross about Crossrail. The Elizabeth line, as it was prematurely named, is a desperately needed piece of infrastructure to drag London’s transport system into the 21st century.

The people who are paying for it, and the commuters destined to suffer two more years of excessive crowds and journey times, have the right to be kept informed about the progress of the project every painful step of the way.

The public was assured in July 2018 that within five months it would be possible to travel from Paddington to Canary Wharf in 15 minutes. In November 2019, it became clear that even another two years will not be enough for “software development for the signalling and train systems, and the complex assurance and handover process for the railway”.

Passengers and taxpayers understand that ambitious projects go wrong, and many of us, from experience, will mentally factor in an extra 50 per cent of time and money to whatever the politicians promise.

Crossrail will transform the capital when it finally opens. But besides the short-term detriment the delay has caused, a bigger danger is that future projects will be scuppered by scepticism.

The first casualty of lousy project management is usually the next big idea. High Speed 2, the desperately needed north-south link, is already looking extremely vulnerable to short-term political expediency. The line will have to be built one of these decades to ease the inter-city capacity crunch.

If it opens in 2040 or 2050 rather than 2030, the Crossrail bunglers will bear a share of the blame. For it to survive, we need to know the truth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments