How lethal could a prolonged lockdown be for people on low incomes?

Are there reasons to fear that the longer the lockdown continues, the more the poorest among us will suffer? Ben Chu investigates

We know that the extension of the UK’s lockdown beyond the initial planned period of three weeks will have severe economic consequences.

Some estimates suggest that every month of hardline restrictions on our movements will reduce our annual GDP by 2 percentage points.

That’s significant. Falling GDP translates into lower incomes, jobs lost and livelihoods damaged.

Yet money is not the only metric. There’s education disrupted, families separated, life chances missed, the possibility of a rise in domestic violence. And then there’s health.

“Anything that has an impact on the socioeconomic status, particularly of people who are more deprived, will have a long-term health impact [and] we have to, in our exit strategy, balance all of these different elements which to some extent can be in tension,” said the UK’s chief medical officer Chris Whitty at the government’s daily Covid-19 briefing earlier this week.

So are there reasons to fear that, if the lockdown continues, the poorest among us will suffer the most? Could a prolonged lockdown even be lethal for some?

Here, The Independent surveys the evidence.

Life expectancy

One might assume that economic slumps would be associated with shorter lives but much evidence suggests the opposite, that recessions are, counterintuitively, associated with faster periods of life expectancy increases.

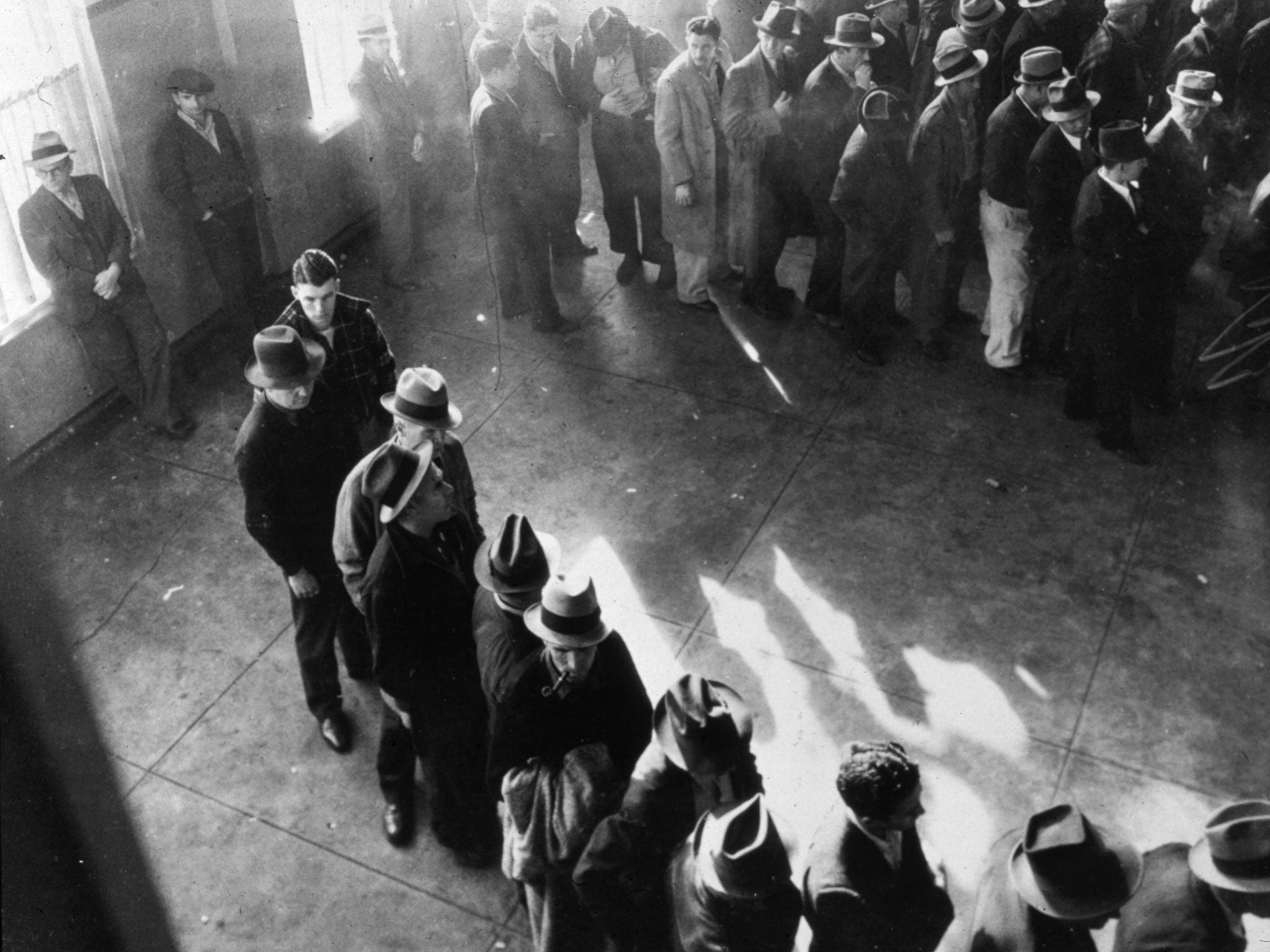

Researchers found that mortality fell and life expectancy increased for almost all demographic groups in the US during the four years of the 1930s Great Depression. This was a period in which the US economy fell by 20 per cent and US unemployment hit 26 per cent.

Another US study found similar results for the impact of postwar American recessions.

Nor is this merely an American phenomenon. Evidence from the 2008-09 global financial crisis suggests that the mortality rate declined faster in European countries, including the UK, that had a larger slump than in those that had a smaller hit to their economy.

Why might this be? Researchers hypothesise that a period of recession, and falling incomes, might result in less risky and health-damaging behaviour such as heavy drinking. Less driving, for economic reasons, might result in fewer road traffic accidents.

However, evidence from Latin America does suggest an overall increase in mortality in recessions.

“There does not appear to be a ‘typical’ mortality response to recession,” say researchers at University College London’s Institute of Health Equity.

“While some causes of mortality will increase, others will fall, and the impacts these will have on overall mortality will differ between populations.”

Suicide

Those US studies of the Great Depression might have shown a positive impact on mortality but they also showed a spike in suicides.

Further, a study of European countries and the US found 10,000 “additional economic suicides” between 2008 and 2010 as a result of the global financial crisis – although other work suggests the scale of the increase is also affected by the scope of the existing welfare safety net.

There was a major spike in suicides in Greece during that country’s recent exceptionally severe economic and financial crisis

Researchers attribute this to job losses, indebtedness and people losing their homes because of mortgage defaults.

Health

Research on the health impacts of recessions is much more clear cut than the research on longevity: it is negative and significant.

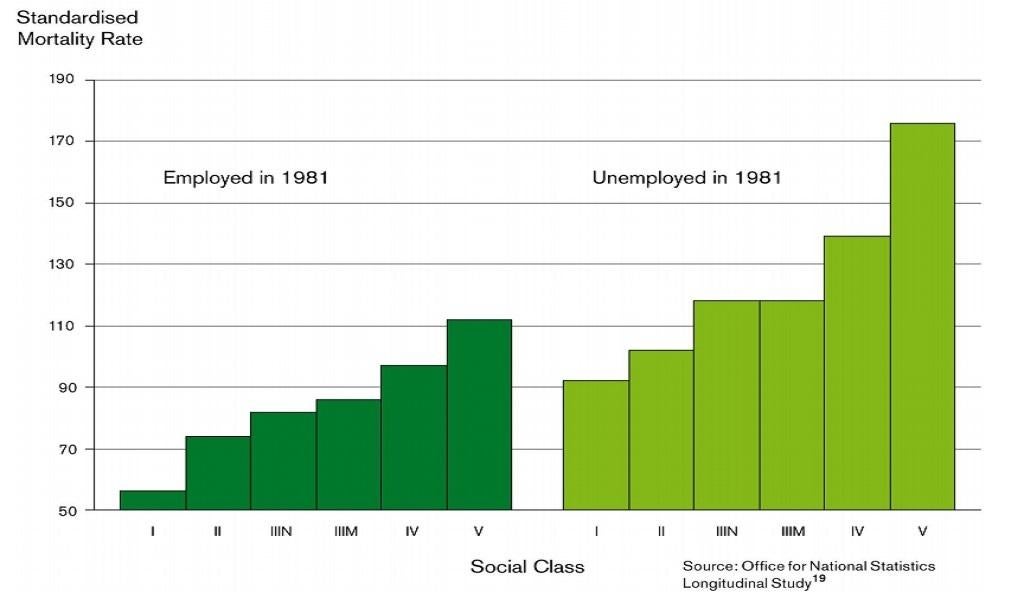

And health inequalities tend to rise too, with those on low incomes hit harder, probably because they are more at risk losing their jobs. There is a well-established link between joblessness and worse health.

Evidence from the 1981 recession in the UK suggests the death rate of those who were unemployed in that slump was higher than that of those who were employed.

And for those from the most deprived socioeconomic communities, the gap was very large indeed.

Researchers at the Institute for Fiscal Studies say evidence is already emerging that low-income families are being disproportionately affected by the lockdown because they are less likely to be able to work from home like white collar professionals.

The IFS estimates that if UK employment were to fall as it did during the 2008 recession an additional 900,000 people of working age would be expected to suffer from a chronic health condition.

Researchers also warn that a population’s mental health suffers in recessions.

Unemployed workers are twice as likely as their employed counterparts to experience depression, according to one US study.

The UK mental health charity Mind reported a doubling of calls to its helplines during the last recession. There’s also evidence that these problems are especially concentrated in more deprived areas.

The trade-off

It’s important to note that we have never experienced a lockdown like this before so it’s impossible to look directly to the historical record to judge what the short and long-term health effects will be.

The circumstances of mass job losses, combined with personal confinement and a closure of the entire leisure industry, are entirely new.

Yet we do have evidence of the health impact of previous recessions which might serve as a guide.

And that evidence does strongly suggest that it will be the least well-off who suffer the most, the longer this shutdown of economic activity continues.

One has to weigh, against this, the fact that the health of the less well-off would suffer too in the event of the lockdown being lifted before the pandemic was contained.

Data from New York shows that poorer people are being disproportionately hospitalised by Covid-19.

Claims that these economic and social restrictions, and accompanying recession, are likely to kill more people than Covid-19 are not well grounded – much will also depend on the policies enacted after the slump.

Nevertheless, the UK’s chief medical officer is certainly justified in saying this trade-off is one of the key judgements that ministers will confront in deciding whether to lift the lockdown.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments