Could local lockdowns end up making left behind places even poorer?

Are the localised Covid restrictions exacerbating the gaping regional inequalities and making the ‘levelling up’ ambitions of the government harder still? Ben Chu investigates

Is the coronavirus actually levelling Britain down?

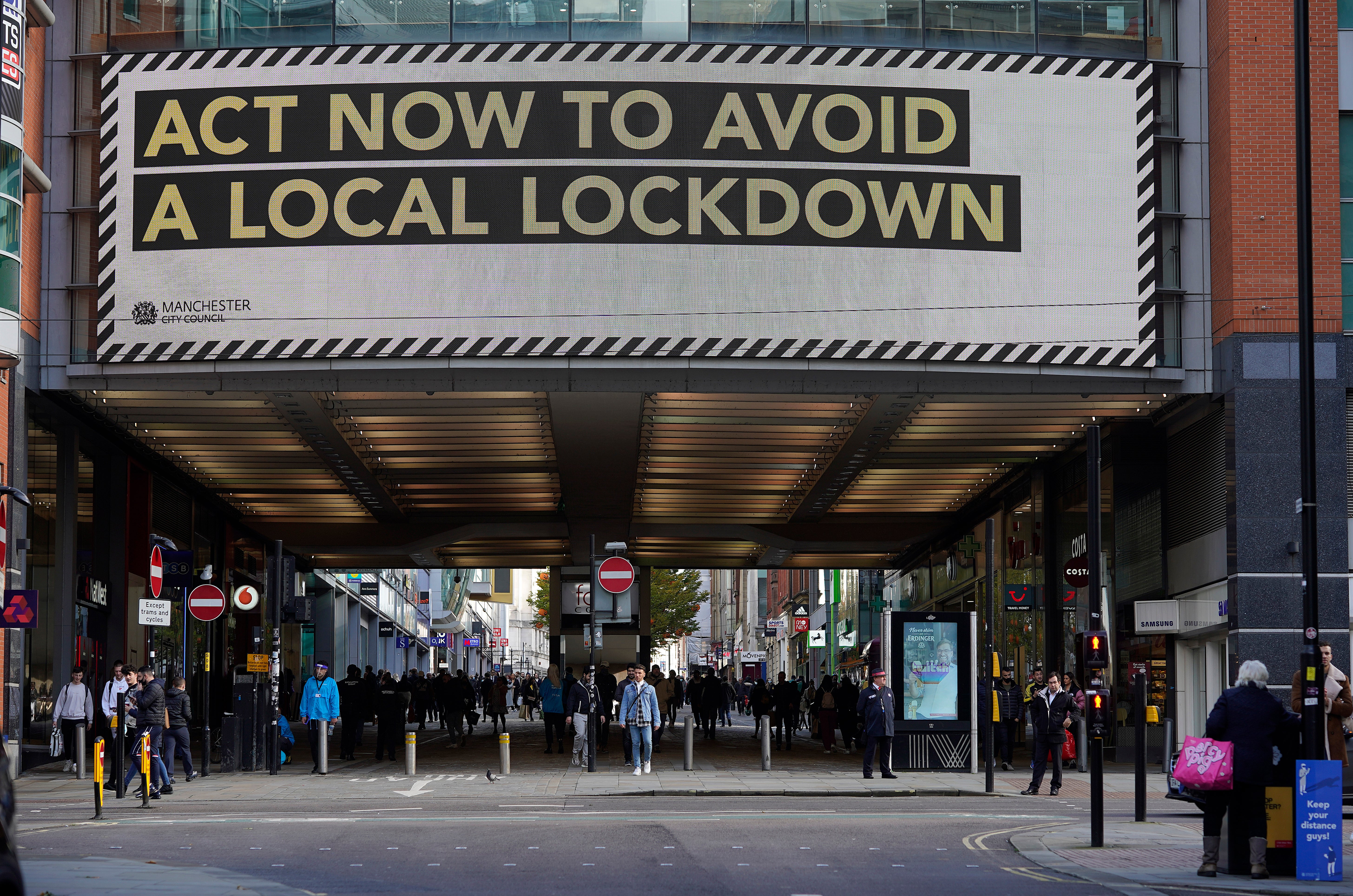

Different parts of the UK have been subject to different levels of restrictions in this pandemic. On the face of it this discrepancy is justified by the varying rates at which the infection is spreading around the country.

In England, parts of the northwest are currently registering around 80 new daily cases per 100,000 people – which means the epidemic is spreading around eight times faster there than it is in the southeast.

Yet these unequal health restrictions are, some argue, bringing dangerously unequal economic impacts as well.

Political leaders in Leeds, Manchester and Liverpool have pointed to the devastating economic impact of the tighter restrictions in their areas, particularly on hospitality. Liverpool’s mayor, Joe Anderson, says that many of these businesses in his city are “teetering on the brink”.

And now these regional leaders are warning that they would not support any of the further local restrictions being mooted by central government, such as closing non-essential shops as well as pubs and restaurants.

“Our response should consider broader local impacts than absolute numbers of infections [such as] impacts on jobs and business [and] effects on poverty and deprivation,” they have told national ministers.

There are rather toxic suspicions too of political bias in the way these restrictions are being imposed, with some pointing out that certain of the localities slapped with new restrictions have had lower numbers of new infections than others which have been spared them.

“Are you more likely to have social lockdowns earlier and for longer and at a lower confirmed case rate if you are a northern, less wealthy, non-Conservative voting local government area?” asks Professor Dominic Harrison, the director of public health for Blackburn with Darwen.

Some have pointed out that Richmondshire, which includes the Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s relatively well-heeled constituency, has not faced additional restrictions despite registering a relatively high number of new cases.

Professor Harrison argues that some of the more “economically challenged boroughs” are being restricted more rapidly, saying that “this has the effect of exacerbating the economic inequality impacts of the virus in those areas”.

All this raises the troubling question of whether the Covid restrictions could end up exacerbating the gaping regional inequalities that the UK suffered from going into this crisis – and making the “levelling up” ambitions of the government harder still.

New analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) finds that many of the traditionally “left behind” areas of the UK – former industrial towns in the north and midlands – have not, in fact, been particularly hard hit by the short-term economic impact of the pandemic.

Yet the think tank notes that long-struggling coastal communities such as Blackpool, Great Yarmouth and the Isle of Wight, which rely on tourism and hospitality, have.

It also says that the centres of some relatively deprived northern cities that have been hit hard by the pandemic, such as Liverpool and Glasgow, can also reasonably be considered “left behind” in terms of their levels of deprivation.

Such places face what the IFS describes as a “double whammy” from the pandemic.

That supports the case for the kind of remedial financial support from national government demanded by regional leaders if they are being forced to obey stricter restrictions. And ministers seem to be moving in this direction.

However, Paul Swinney of the Centre for Cities argues that when considering the long-term impact of local lockdowns and the pandemic more broadly it’s vital to think about the kind of businesses that drive an area’s productivity – its exporters and high-value added business services and knowledge-economy firms.

“The challenge of levelling up in the first place is that these places haven’t got very many high-productive, exporting industries,” he says.

If lockdown restrictions don’t affect [high productivity] parts of the economy then you wouldn’t think that it would compound the levelling up challenge

“If lockdown restrictions don’t affect that part of the economy then you wouldn’t think that it would compound the levelling up challenge.”

The damage to hospitality in these areas is more of a short-term economic problem.

“Pubs, bars and restaurants are the kinds of business that feed off a strong economy. They’re not really the engines of an economy,” says Mr Swinney.

That’s not a reason, though, to be unconcerned about the existential challenges they are facing in more deprived parts of the country.

“If you do see [these sectors] having to lay people off because of the restrictions clearly there’s an impact there. How quickly will they get a job again? Will there be any scarring effects? That’s where the concern should be.”

Regarding those suspicions of political bias in lockdown policy it’s not entirely clear that the government would have much to gain by sparing certain areas heavier restrictions. If the virus gets out of hand those restrictions will come sooner or later.

The problem lies more with the lack of transparency about the lockdown decision-making process and the question of under what criteria new restrictions are imposed.

“You would have thought that politicians would have learnt by now that if you don’t have clear guidance as to why you’re doing things it’s always going to open up debate over bias,” observes Mr Swinney.

Local mayors and political leaders in the north are calling to be given control over any new health restrictions. Allowing local leaders the final say on when and whether to close pubs or universities might prove unrealistic given the regional and national spill-over effects of such decisions. In the end national government is always going to be heavily involved.

Yet experts generally agree that local leaders should be a much bigger part of the decision-making process. The centre should also hand down more responsibility over infrastructure such as testing and tracing, where local knowledge is crucial to making it effective.

A crucial long-term policy lever for bringing left-behind areas back into the caravan of national prosperity has long been recognised as handing down authority over areas such as skills, investment and transport.

Devolution now seems vital for both levelling up and for beating the pandemic.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments