As UK faces its worst slump since the Great Frost of 1709, history shows our economy is no match for nature

The likely global recession triggered by the novel coronavirus is part of a much older tradition

When the Office for Budget Responsibility predicts national income will fall by some 35 per cent over just a few months, that is a truly historic slump. It is useful to place it in some perspective.

Assuming that the economy “bounces back” fairly robustly afterward the lockdown and growth returns – far from guaranteed – it would leave the British economy in 2020 overall about 13 per cent smaller than it was in 2019. That would still be the biggest annual fall in economic activity in centuries – since 1709 in fact.

That of course begs the question: What on Earth happened in 1709 to spiral the economy into dropping by about 15 per cent (though the further back you go, the hazier GDP estimates get). Well, it wasn’t a war or one of the many pandemics – or plagues, as they were known then – that hit the world periodically.

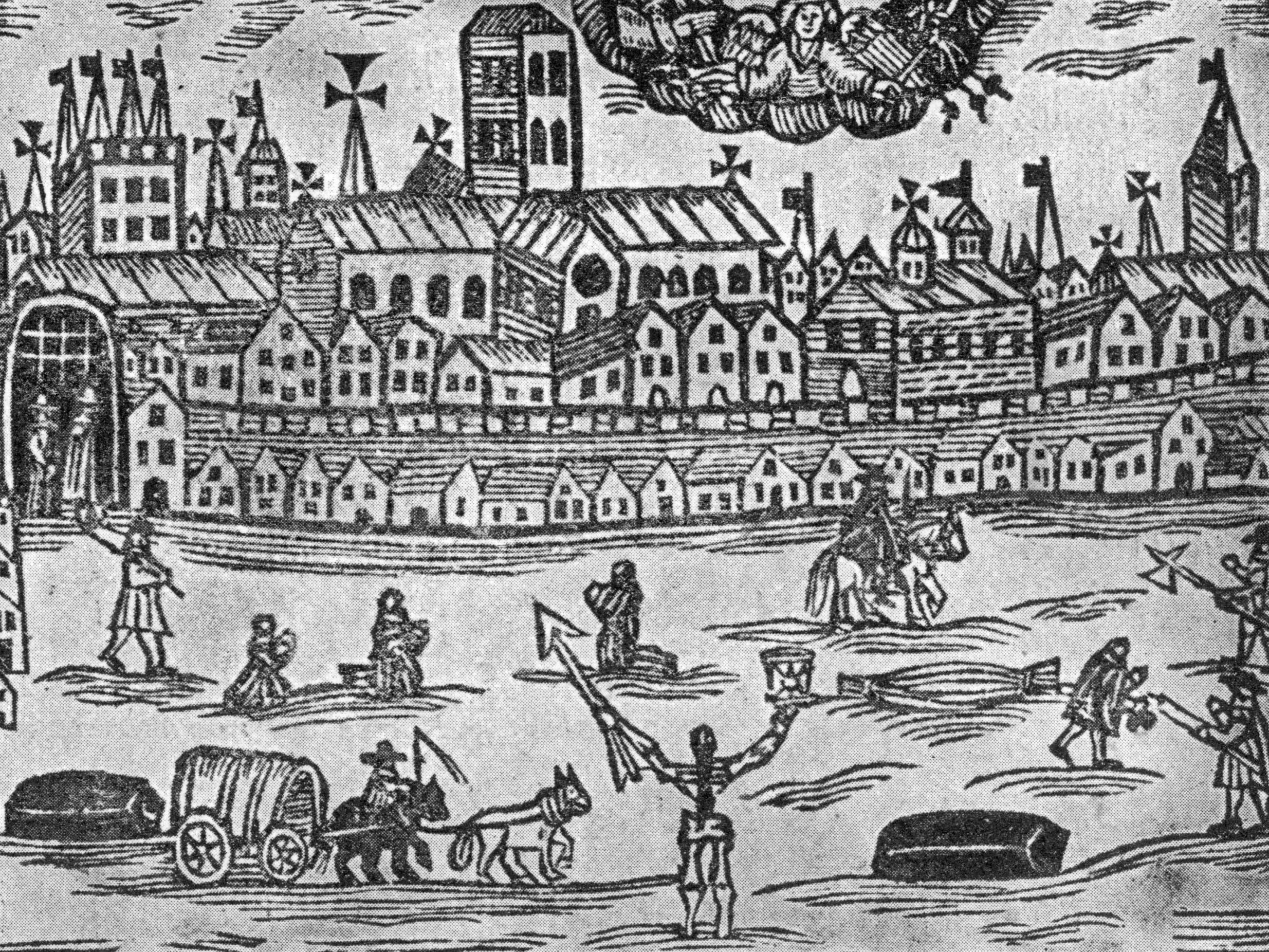

It was, though, a natural disaster: the Great Frost or Great Winter of 1708-09. This was simply a prolonged and inexplicable burst of cold weather that so affected crops it wiped out much of the subsequent harvests. The Baltic froze, crops failed, thousands starved. It is said to have been the coldest winter in the past 500 years, and an extreme episode in a long era of global cooler weather. To this day the “Little Ice Age” of 1450 to 1800 is the subject of scientific interest, the more so because of what it might tell us about climate change.

However, the Britain of 1700 was a very different place. The reason why the Great Winter had such a drastic economic impact is that most of the British population of 6.2 million or so relied on agriculture and allied occupations for their livelihood. No crops meant nothing to eat or sell, and no income to buy anything, let alone save or invest. It was, of course, long before the welfare state or modern economics. There were no business support schemes and the starving unemployed, if they were lucky, would go to the local parish guardians to receive some dole, or “poor relief” - the universal credit of its day.

Even if they had the funds and the prudent instincts, stockpiling food was difficult when the only preservatives were sugar, salt and smoking. There was international trade and imports of food and drink, but these tended to be expensive. Tea, for example, was a luxury novelty, locked away by aristocrats in ornate silver caddies. Gin, on the other hand, was notoriously cheap and it was perfectly easy to get blind drunk for £3 (in today’s money).

Earlier natural disasters – including pandemics – also hit the small farming-based economy hard. By the time of the “Year Without a Summer” (1816) the economy has diversified into industry and exports of manufactures. So the eruption of an volcano in what’s now Indonesia that expelled so much dust it blotted out the sun across much of the world was less damaging than it might have been, with disaster confined to farming.

There are other horror stories behind the economic stats. The Black Death after 1347, with its 50 per cent plus mortality rates, and subsequent plagues of the 1360s had a commensurate and longer lasting and depressing effect on economic output (though wage rates for the surviving peasants boomed).

The Great Plague of 1665, centred then as now on London, finished off around 750,000 Britons, but the main impact was from closure of businesses during the confinement – early self-isolation and social distancing. The economic effects were severe, but not long-lasting. Much the same goes for the flu pandemic of 1918-19, which was ameliorated by a short sharp boom after the Great War as pent up demand was released. The slump of 1920-21 – about 10 per cent of UK GDP came at the end of that brief upturn.

Every other recession or depression up to now has been effectively man-made, either through wars, financial and banking crashes, government mismanagement or spikes in commodity prices caused by wars or cartels. The brief deep depression of 2020 is part of a much older tradition, and, like the bush fires and of the freak climate events of recent years, a reminder that the force of nature can be greater than even the most sophisticated of societies.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments