‘Birdgirl’ Mya-Rose Craig: ‘I never used to see anyone who looked like me in the countryside’

Young star of the environmental activism scene speaks to Emma Snaith about birding, Cop26 and her fight for more access to nature for all

“I was nine-days-old the first time I went bird watching,” Mya-Rose Craig says.

Her dad couldn’t pass up the opportunity to see a very rare lesser kestrel visiting from Europe. So her family went to the Isles of Scilly to see the bird just over a week after she was born.

Now 19 years old, Craig is thought to be the youngest person to have seen half of the world’s bird species. Also known as “Birdgirl”, she has seen more than 5,410 of the world’s 10,738 species after trips to 38 countries.

And last year, she became the youngest person from Britain to receive an honorary doctorate – a doctor of science degree awarded by the University of Bristol for her conservation work and her advocacy.

Craig says that “everything comes back to birds for me.” She adds: “That’s where all of my race and climate activism came from.”

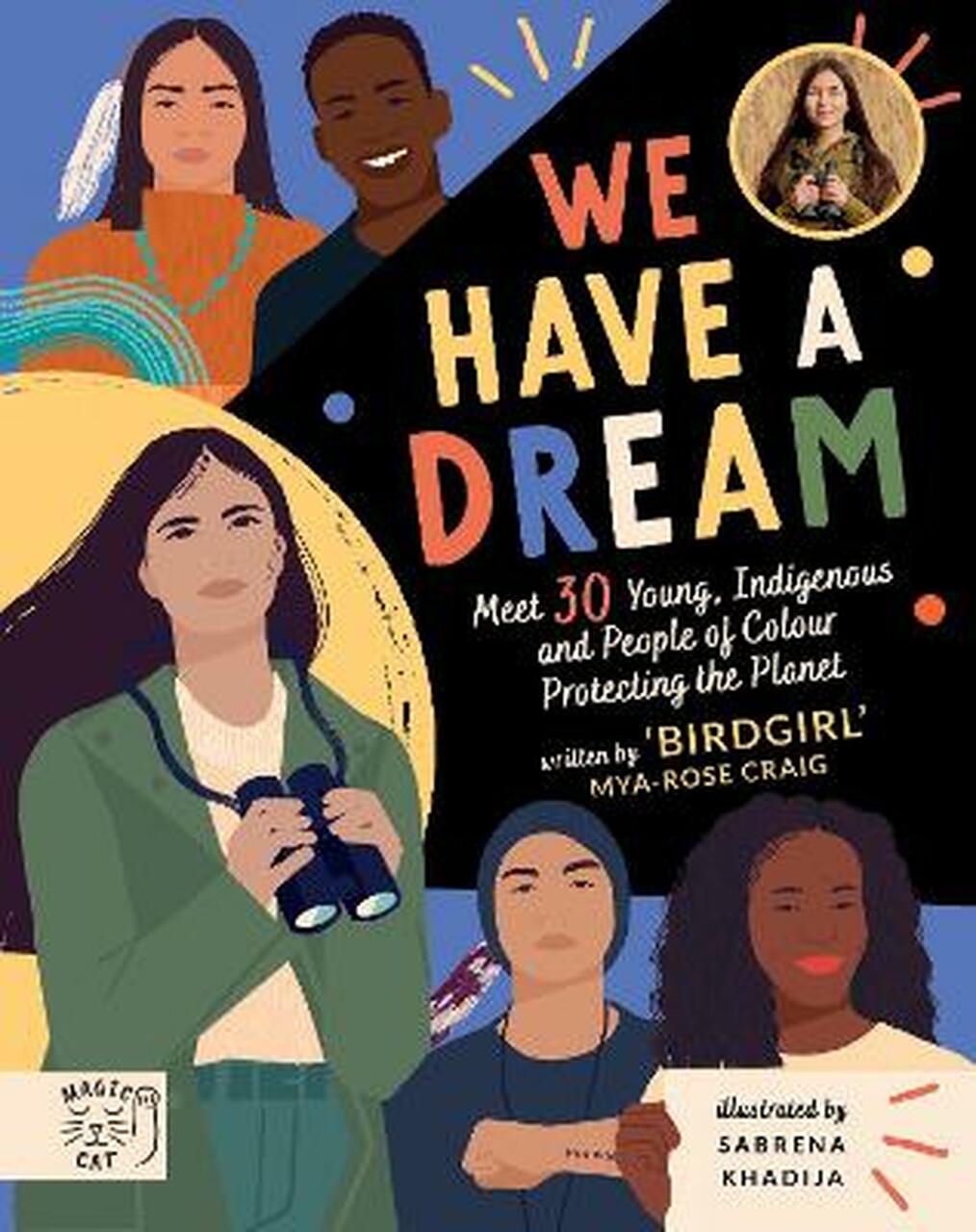

Indeed, Craig is not just a birdwatcher, she’s also an activist for global climate justice and diversity in environmentalism. Last week, she released her book We Have a Dream, which tells the stories of 30 young indigenous people and people of colour striving to protect the environment. From Autumn Peltier, an indigenous clean water advocate in Canada, to Scarlett Westbrook, a British-Kashmiri activist fighting for climate education, the book spotlights the young activists who often are not heard in global conversations.

Craig, who is of British-Bangladeshi heritage, has herself campaigned since the age of 13 to improve diversity in conservation work. She says her experience spending a childhood outdoors made her realise how few opportunities there are for people of colour to explore nature, let alone get involved in the environmental movement.

“I was very aware that I never used to see anyone who looked like me out in the countryside,” she says, while recounting her upbringing in the Chew Valley near Bristol. “I found it really sad that other kids weren’t getting the same opportunities that I had.”

A recent independent review commissioned by the government found that many British people of all ethnicities saw the countryside as a “white environment”.

So, in 2016 Craig set up her charity Black2Nature to campaign for equal access to nature for all. She began organising a series of nature camps to allow young people, particularly from ethnic minorities, to leave the inner city and explore the countryside.

“For a lot of the kids we worked with, it was a totally alien experience,” Craig explains. “Many had never seen a cow or a sheep before – they were frightened of nature.” But over the course of a weekend at the camps, the children would get the opportunity to go mothing (finding and recording moths), make nest boxes, take photos of nature and, of course, go birding.

Yet Craig says that some of the most important moments of the camps actually came during the discussions they had – from the childrens’ experiences of racism at school to the impact of the climate crisis on communities around the world. Once, when a participant spoke about her family in Sudan dealing with drought, “We looked at how that might be linked to the climate crisis.”

When coverage of climate activism exploded in 2019 following a wave of school strikes and Extinction Rebellion protests, Craig became increasingly aware that the lack of diversity in the environment movement was a worldwide problem.

“I started to realise that it was just the same small group of people – mainly white, mainly from the West – who were getting the opportunity to get interviewed all the time,” Craig says.

She adds that even when the spotlight falls on non-Western activists, they are not considered in their own right. “Almost every non-Western young environmental activist is presented as, say, ‘the Greta Thunberg of China’ when they might not be anything like Greta,” she says.

She adds that no one really knows why Greta Thunberg was made the leader of the climate movement: “Probably including Greta, but it happened.”

Like many young people, Craig stresses the importance of intersectionality in the environmental movement. “To combat climate change, you have to combat racism, sexism and classism,” she says. “All these issues are totally interconnected.”

Craig credits the Black Lives Matter protests last summer with amplifying calls to put racial justice at the heart of the environmental movement. As she points out, “the concept of intersectionality originally came from black feminism in the first place”.

And in the lead up to the Cop26 climate summit this November, the importance of ensuring “climate justice” for developing nations is even more compelling.

“It really annoys me when people talk about climate change being a great equaliser,” Craig says. “Because it’s totally not. Some people are left to suffer and some people hardly feel the impact at all.”

She explains that many of the young environmental activists featured in her book began campaigning from as young as six years old because “they had no choice”. This was especially the case with activists from indigenous communities: “They really are on the front lines of environmental issues and very conscious of them from a young age,” Craig says.

The recent publication of the stark IPCC climate report has added even more impetus to the struggle for climate justice. The report, from the world’s leading authority on climate science, found that the international goal of limiting global temperatures to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels risks slipping beyond reach without urgent and immediate action.

Activists warn that leaders must listen to communities on the front line of the crisis in the wake of the “code red warning”, as they are the people that will be most affected if global temperatures rise above the 1.5C threshold.

In response to the IPCC report, Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate told The Independent: “Even at 1.2C, communities like mine, across Africa and the global south – on the front lines of the climate crisis – are already facing impacts that are destroying livelihoods, dreams and hopes.”

But Craig is “increasingly cynical” about how much progress will actually be made towards lowering global emissions at Cop26 this year.

“Talks and politics are really important. But what I want to see from governments is action. And not in a way that is greenwashing or trying to appease people, but actually fixing the problem.”

Indeed, Craig has seen some of the severe effects the climate crisis is already having on the planet first-hand. Last year she took a ride on Greenpeace’s ship Arctic Sunrise to stage the world’s most northern climate strike on an ice floe in the Arctic circle. And since she began birdwatching as a child, she has noticed ever more species being threatened by a loss of biodiversity and the changing climate.

Despite her cynicism, Craig still plans to go to Cop26 in Glasgow later this year to lobby world leaders to cut emissions faster. “I think you have to be quite optimistic to be an environmental activist,” she says. “It gets really miserable really quickly otherwise.” By the time the climate summit begins she will have started studying for a degree in human, social, and political sciences at the University of Cambridge.

Will she slow down now she’s starting university? “Probably a bit,” Craig admits. But she’s keen to do more grassroots work with Black2Nature and continue to help run nature camps for children.

And while she is now more conscious of the climate impact of international travel, Craig says she is “always going to be birding”, wherever that might be, and especially when things begin to feel overwhelming.

“My favourite things to look out for at this time of the year, until the autumn, are all the swifts, swallows, house martins and sand martins swooping around. There’s a whole bunch of house martins nesting in a house in my village at the moment.”

“Everything is so big a lot of the time,” she says. “Sometimes I just need to get back into nature.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments