Migration by numbers: What’s really driving the surge in people coming to the UK?

Despite the government’s focus on students and small boats, they account for a small fraction of net migration. Lizzie Dearden and Holly Bancroft look at what’s behind the rise

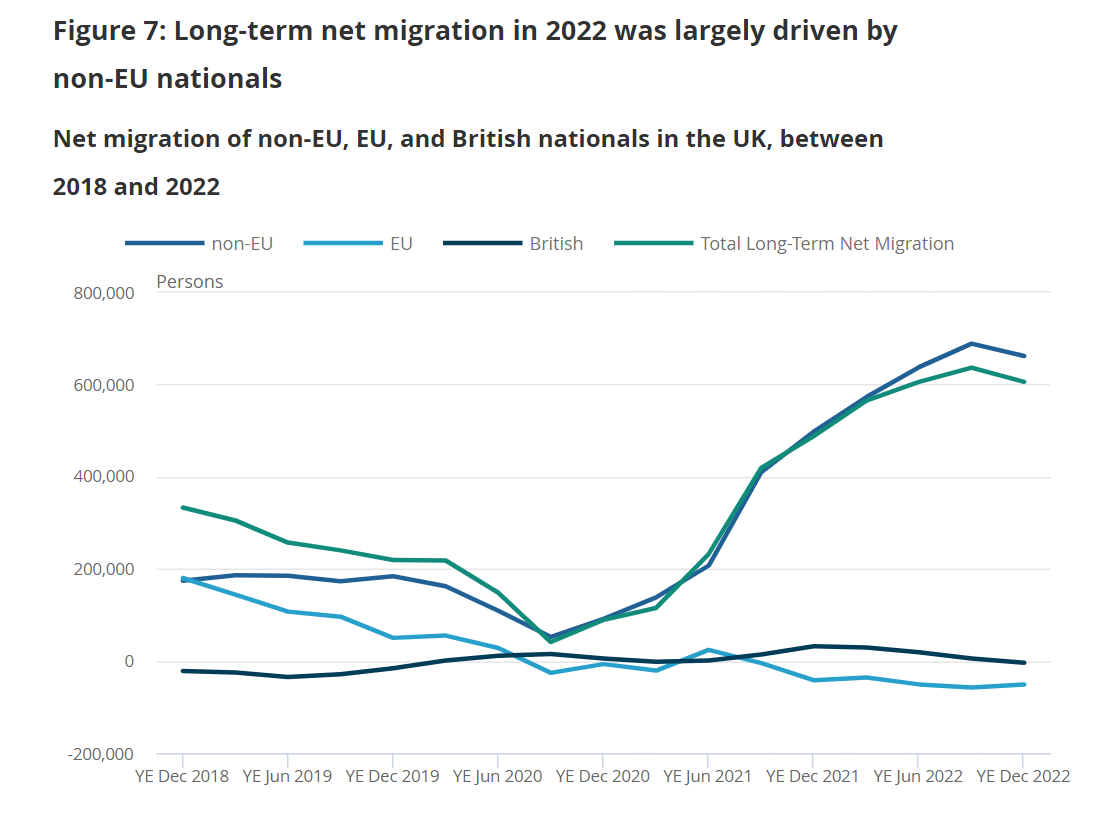

Net migration has hit a new record high, driven by workers from outside the EU moving to the UK, new figures show.

The surge in numbers to 606,000 in 2022 has been driven in part by the effect, in the short term, of government-run humanitarian schemes for people fleeing Ukraine, Afghanistan and Hong Kong, while the number of small-boat crossings in the English Channel has continued to rise.

Suella Braverman has targeted international students with a controversial crackdown on their right to bring family members to Britain while they study, but the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said most students leave when their courses end.

Meanwhile, there is pressure on the government from several industry groups to loosen migration requirements in order to fill labour shortages affecting agriculture, logistics, hospitality and other sectors.

So what are the figures behind the new record?

Net migration

Jay Lindop, director of the ONS’s Centre for International Migration, said: “A series of unprecedented world events throughout 2022, and the lifting of restrictions following the coronavirus pandemic, led to record levels of international immigration to the UK.

“The main drivers of the increase were people coming to the UK from non-EU countries for work, study, and humanitarian purposes, including those arriving from Ukraine and Hong Kong.”

The ONS estimates that in 2022, 1.2 million people arrived to live in the UK long-term – including 925,000 non-EU nationals, 151,000 EU nationals, and 88,000 British people – while 557,000 people emigrated.

Its report said that the number of people coming to the UK from non-EU countries for work, study, and humanitarian purposes had driven high levels of immigration for the past 18 months; that growth was slowing; and that the trends appeared to be “temporary”.

Students

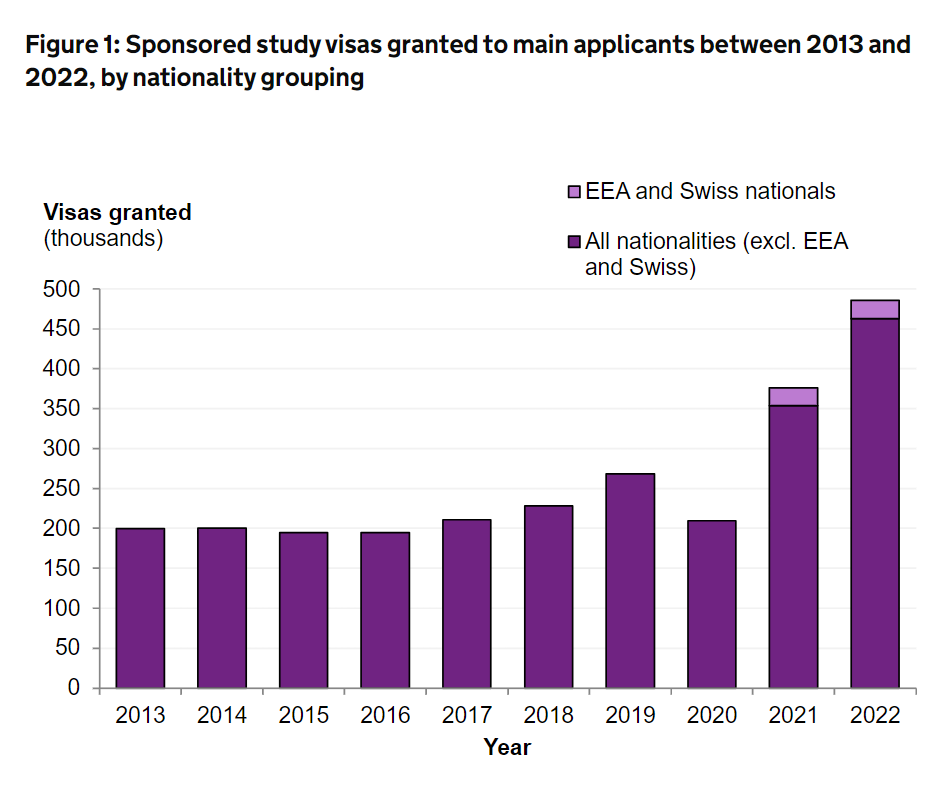

The ONS said the number of student visas issued had risen in 2022, partly because of a new graduate visa allowing students to work in the UK for up to three years after completing their studies.

But days after the home secretary announced controversial restrictions on international students wishing to bring their children and loved ones to live in the UK during their period of study, the ONS said the majority of students still “leave at the end” of their course.

“Those who arrived for study reasons in 2021 are now starting to leave, driving an increase in total emigration from 454,000 in 2021 to 557,000 in 2022,” it added.

The report said a spike in student arrivals in 2021 was a result of the lifting of travel restrictions for those who had previously been studying remotely during the coronavirus pandemic. “Evidence suggests that students typically stay for shorter periods than other migrants and that the majority leave at the end of their study,” it added.

Home Office figures show that, under the current rules on international students bringing their partners and children to the UK, a fifth of visas are granted to students’ dependants rather than to those who are studying.

The highest numbers of student dependants were from Nigeria, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

People coming to the UK for work

When the Brexit withdrawal agreement came into force on 31 January 2020, it ended free movement between the UK and EU states, meaning that EU citizens could no longer work in the UK without a visa.

This has contributed to staff shortages in some sectors, including agriculture, food processing and logistics, as well as leaving gaps in staffing across the NHS.

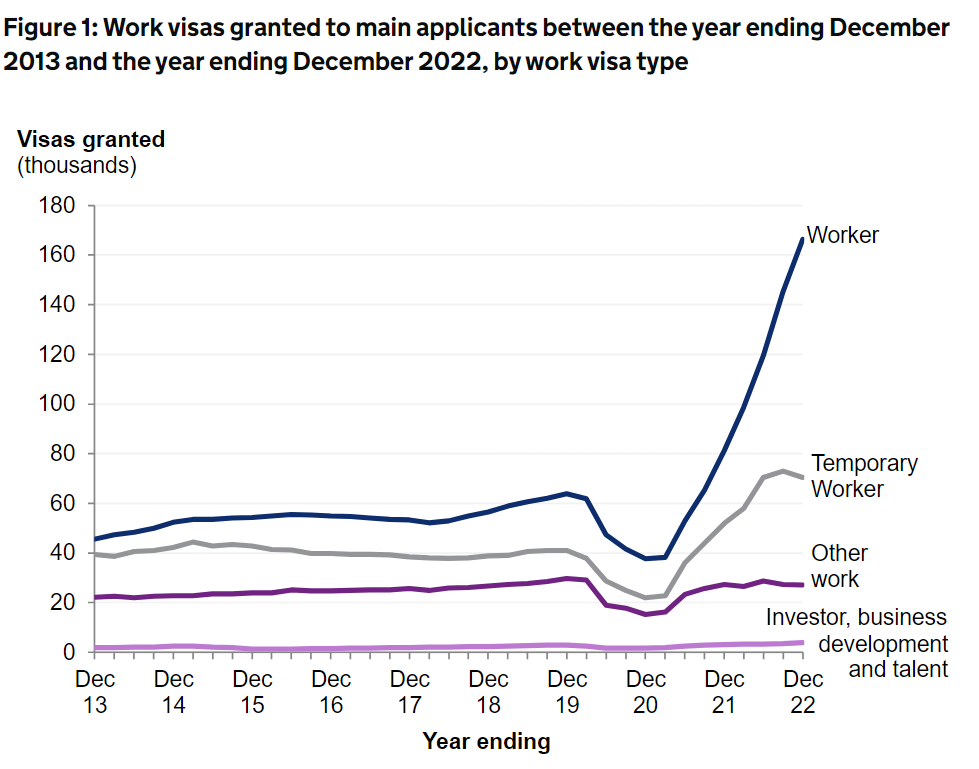

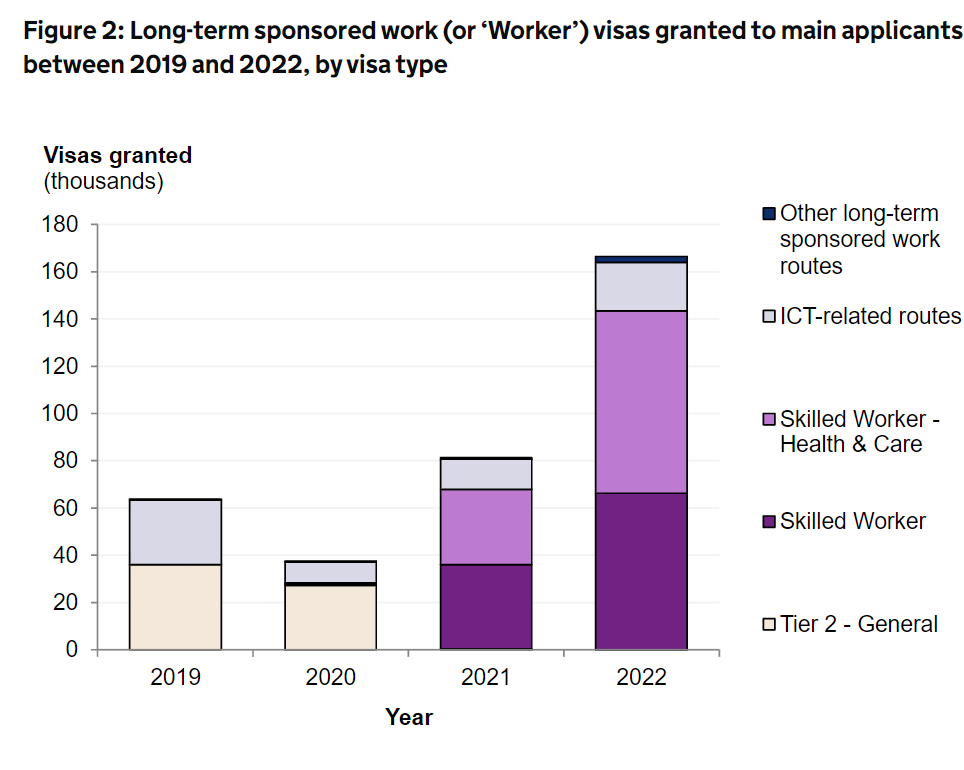

The ONS said that work-related visas accounted for a quarter of non-EU long-term immigration in 2022, being the basis for an estimated 235,000 arrivals compared with 137,000 in 2021.

There has been particular growth in new skilled worker and “health and care” visas, in part due to the expansion of schemes targeting nurses and carers.

More than 70,000 temporary worker visas were granted in 2022, according to Home Office statistics, and more than half of those were for seasonal workers – including those taking on jobs in agriculture and poultry farming.

Only 2,493 such visas were granted in 2019, before the Brexit agreement took effect, and the figure soared to almost 35,000 in 2022.

A Home Office report said grants of temporary worker visas had risen by 72 per cent in that period, adding: “The increase in temporary worker visas has been largely driven by the ‘seasonal worker’ visa, which allows a person to do seasonal horticulture work or poultry production work.

“Visas granted to seasonal workers have risen from 2,493 in 2019 to 34,532, reflecting the increase in this route’s quota from 2,500 in 2019 to 40,000 in 2022.”

Despite the rise, several sectors are still reporting staff shortages, which are driving up wages as businesses attempt to recruit and maintain staff, and increasing costs to consumers.

Ms Braverman has claimed that the British people must “do things for ourselves”, saying that “there is no good reason why we can't train up enough truck drivers, butchers, fruit pickers, builders, and welders”.

But industry groups have hit back and said that years of efforts to attract more applicants, including government-sponsored recruitment campaigns, have proved that migrant workers are necessary.

Asylum and small boats

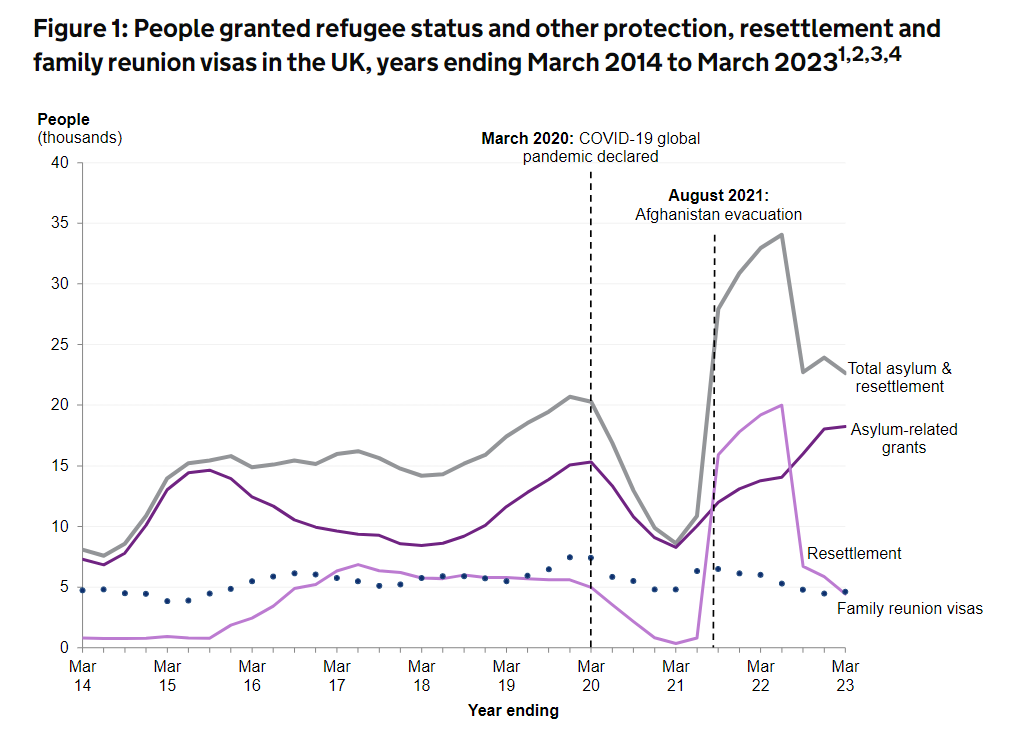

Figures released by the Home Office show that a new record of almost 45,000 people crossed the English Channel on small boats in the year to March 2023, with Afghans remaining the top nationality.

But the arrivals account for less than half (44 per cent) of the total number of people claiming asylum in the UK.

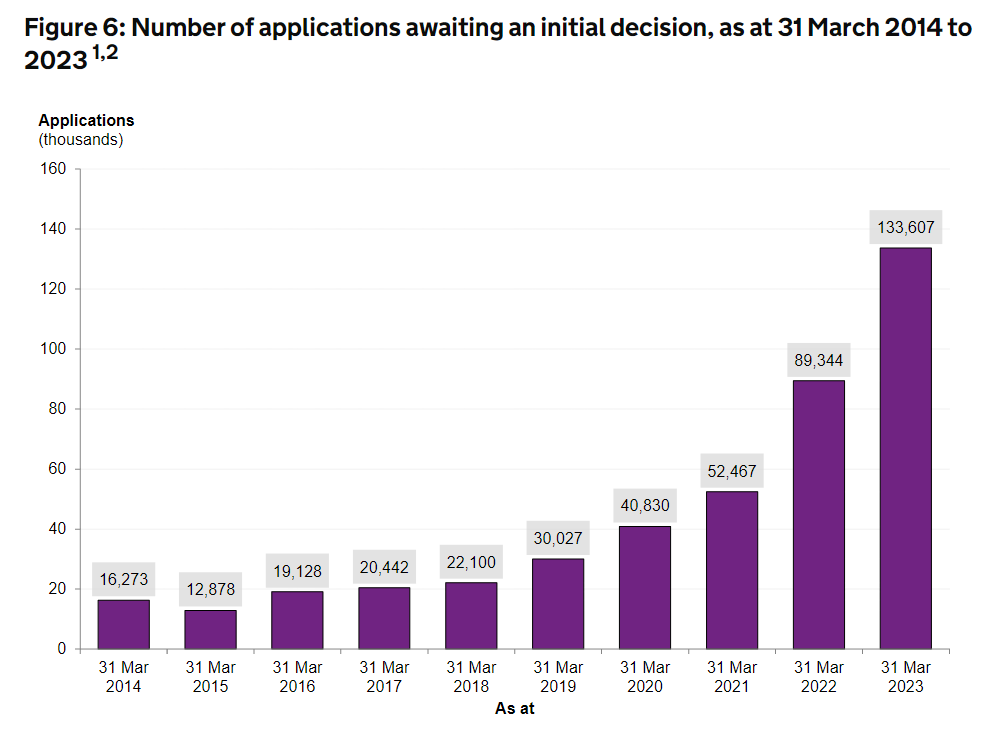

The asylum backlog has hit a new record high, with almost 173,000 people awaiting an initial decision in March – passing a previous all-time peak in 1999.

A Home Office report said that just 1 per cent of small-boat migrants who applied for asylum in the past year had received an initial decision on their claim.

Because the Home Office is legally required to support destitute asylum seekers while it considers their claims, the backlog is driving up the cost of hotel accommodation, and triggering controversial plans to house thousands of people on former military bases and barges.

The government has created the power to ban people from being considered for asylum if they passed through safe countries such as France on their way to the UK, but it has failed to replace the EU returns agreements lost during Brexit, meaning there are few places they can be deported to.

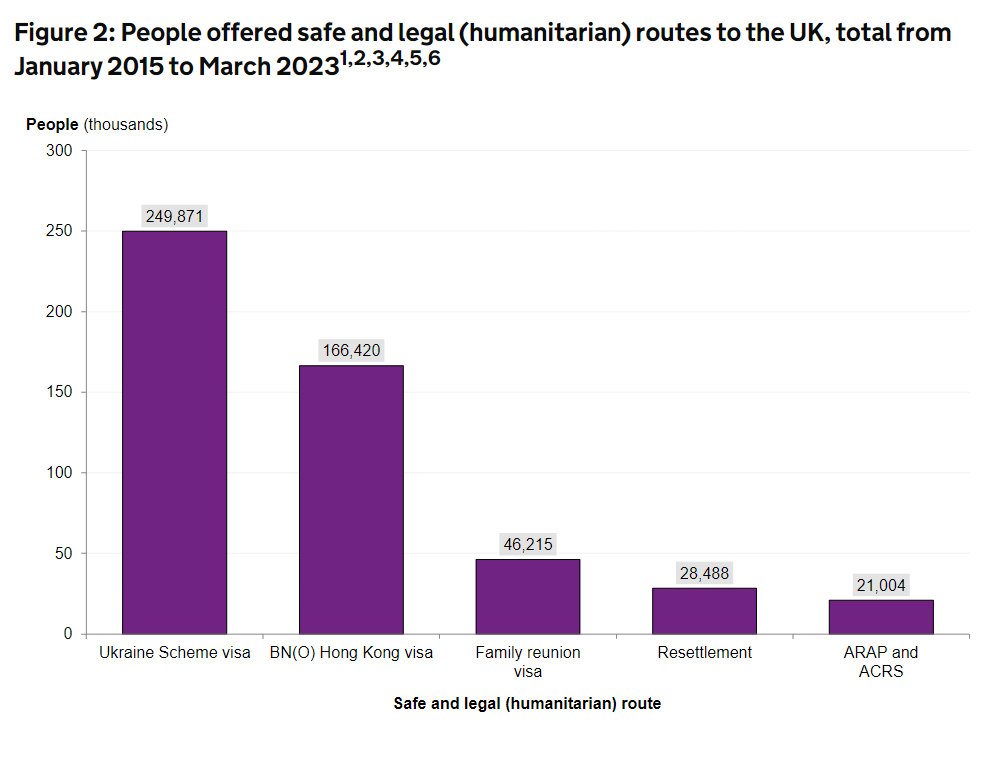

Home Office figures show that between January 2021 and the end of March this year, 55,500 asylum seekers were considered ineligible to stay. Some 24,000 “notices of intent”, including threats of deportation to Rwanda, were sent out – but only 23 people were deported because they were considered ineligible, and “27,644 individuals were subsequently admitted into the UK asylum process for substantive consideration of their asylum claim”.

Tim Naor Hilton, chief executive of Refugee Action, said: “The human cost of the failure to process asylum claims is staggering. Many people wait years for a decision, in which time they’re forced to live in poverty, banned from work, segregated from communities and detained in run-down hotels.

“The government’s Illegal Migration Bill is going to make things much worse. People will still have to make the deadly Channel crossing, because this bill creates no new routes for people to safely reach the UK, while our refugee resettlement schemes are failing.”

Afghan and Ukrainian humanitarian routes

An estimated 172,000 people arrived in the UK via humanitarian routes, such as the schemes designed for those leaving Hong Kong, Ukraine and Afghanistan, in 2022. This was an increase from 57,000 in 2021.

The ONS said 114,000 Ukrainians were estimated to have come to the UK last year, and 52,000 came under the British National (Overseas) visa scheme, which is mainly for Hongkongers. This scheme does not involve making an asylum claim, nor does it grant people refugee status.

The ONS revised down the numbers of Ukrainians they believe will settle in the UK long-term, with unpublished “internal Home Office analysis” showing that some were leaving the country within a year.

Approximately 6,000 people came via other resettlement schemes in 2022, compared with 18,000 in 2021. They mainly arrived through the Afghan citizens resettlement scheme (ACRS) and the Afghan relocations and assistance policy (Arap).

Since the fall of Kabul, a total of 40 people have now come to the UK under the general scheme for at-risk Afghans – ACRS pathway 2 – and only 14 people have been resettled through a dedicated scheme for GardaWorld contractors, British Council workers and Chevening scholars.

Under the Ministry of Defence’s Arap scheme, 4,161 people were relocated to the UK in 2022, and 55 were also brought to safety in the first quarter of 2023.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments