Marcus Aurelius: a philosopher-king, or a king that dabbled in philosophy?

Our series continues with the philosophically inclined Roman emperor, the Stoic who examined free will and what we can control and what we cannot

In his masterpiece, the Republic, Plato argues that the just state is ruled by the ones who know the Good, and at the top is the philosopher-king, a man born and quite literally bred to rule.

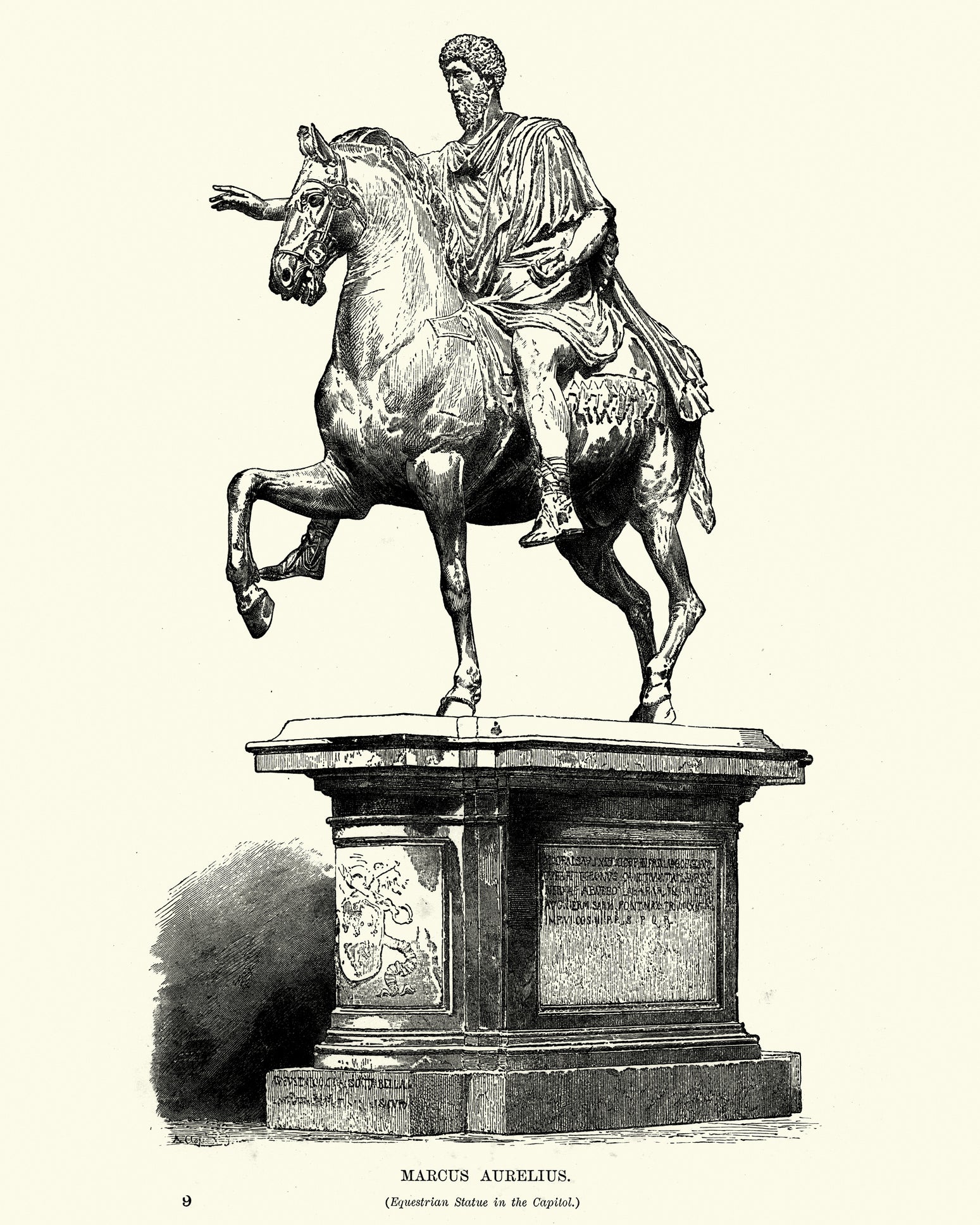

While it might be tempting to think of Marcus Aurelius (AD121-80) as a philosopher-king, it would be a mistake. Marcus was a philosophically inclined Roman emperor, but not a philosopher-king in Plato’s sense. Among other things, he did not undertake the rigorous programme of study required by Plato, and anyway, the philosophy Marcus espouses, though Platonic in places, is clearly generally Stoic in nature. However, it would also be a mistake to overlook Marcus, to take him for a second-rate thinker who happened to be an emperor. We have, in his writings, nothing less than a kind of distillation of Stoic philosophy that is filtered through the practical demands of someone in possession of monumental political power.

His route to power was unusual. Marcus was adopted and brought up well by his uncle, Emperor Antonius Pius (himself adopted by Emperor Hadrian). By all surviving accounts, Marcus was an excellent student of rhetoric, poetry and law, but he seems to have taken an early and very keen interest in philosophy, particularly the writings of the Stoic Epictetus. At a precocious age, perhaps as young as 11, he began to dress plainly and follow what he took to be a Stoic’s severe regime of study, frugality and self-denial. Perhaps he went too far, because there are reports that his health suffered.

On the death of Antonius, both Marcus and his worthless brother Lucius, also adopted by Antonius, ascended to the throne. It is clear that Marcus could have ruled alone, but remarkably he chose to offer Lucius a joint rule. They shared power until Lucius’s death in AD169. Marcus then ruled alone, and by all accounts generally well, until his death, possibly of plague, while conducting a campaign near the upper Danube.

If his death sounds unpleasant, it is nothing compared to Rome’s troubles during his reign. He was almost constantly at war with Parthia; barbarians threatened at the northern borders of Italy; he spent years fighting German tribes along the Danube; he suppressed two revolts by recalcitrant lieutenants; his possibly faithless wife, Faustina, died suddenly; Rome suffered at least one major plague during his rule, as well as famine, floods, fires and earthquakes; and all but one of his children died young. His surviving child, Commodus, was vile and would not have been much comfort.

Writing the meditations

In the midst of such strife, probably towards the end of his life, he wrote what has come down to us, rather miraculously, as the Meditations, which seems like his private diary. The work is manifestly not a standard philosophical treatise, with sustained argument for some well-articulated position. Instead we have a journal of disconnected musings, aphorisms and personal remonstration. The standard, probably excessively romantic view of the work is that Marcus wrote a few lines each night, at the end of a day’s campaigning, during lonely vigils by a moonlit Danube. It may well be true.

Although Marcus was influenced by Plato, Heraclitus, the Cynics and others, it would be impossible to understand the Meditations without seeing it in the light of Stoicism, and in particular the writings of Epictetus. The Stoics were named for the stoa poikile, the painted porch or colonnade on the north side of the Agora where they met in ancient Athens. The modern expressions “being philosophical” or “stoical” about misfortune come from their views.

Stoic philosophy

The Stoics regard nature as itself divine and cyclical – the thinking is clearly pantheistic – consisting in cycles of life and cataclysmic conflagration, eternally repeated. The later Stoics concerned themselves more with ethics than metaphysics, and certainly the practical Roman mind of Marcus is preoccupied almost entirely with how one ought to live. Nevertheless, the view that nature is somehow both divine and heading in a certain direction, despite our choices, partially explains the Stoic’s view that a life led in harmony with nature is the best life, the virtuous life. It also explains the Stoic’s famously steadfast indifference to fortune and misfortune alike. Anything that happens to us is a part of the unfolding of a divine plan that is both beyond our power to influence and, itself, ultimately good.

A Stoic image which makes the point is of a dog tied to the back of a wagon. When the wagon moves, the dog can either be dragged yelping and barking and strangling itself by pulling in the opposite direction, or it can calmly go along with it. The dog heads off in the same direction no matter what it chooses to do; its only real choice being how it copes with its settled fate. As Marcus continually reminds himself, a Stoic must make a distinction between what is up to us and what is not up to us.

In this he echoes Epictetus: “Up to us are opinion, impulse, desire, aversion… Not up to us are body, property, reputation, office.” If you make the mistake of supposing, for example, that your social standing is up to you, within your sphere of control, you will be unhappy; you will take yourself to be harmed by those who overlook you for promotion and lament your failures. The failures, though, are not yours. You only have control over your opinions and attitudes, and here alone is virtue possible for the Stoic.

Our reactive attitudes to what goes on are up to us, but what actually happens in the universe is the unfolding of providence, itself good, but not up to us. One might rationally regard health, wealth and power as preferable to their opposites – the Stoic would consider them “preferable indifferents” – but disappointment at failing to acquire such things as well as satisfaction upon their acquisition is pointless and irrational. Attaining such things is not up to us.

Thus Marcus: “Try living as a good man and see how you fare as one who is well pleased with what is allotted to him from the whole and finds his contentment in his own just conduct and kindly disposition.” A good or virtuous man accepts his lot, whatever it might be, and this follows from the recognition that whatever life the universe extends to us, it could not have been otherwise. The universe unfolds, and this itself is good, regardless of our myopic view of it. A good man is therefore someone who recognises this, is pleased with whatever he has, and looks only to what is in his control: his reactions and his disposition. The good man harmonises his inner life with providence.

The problem of free will

Marcus lists one’s conduct as something that is within one’s control, and here there is a tension in Stoic philosophy, which Marcus seems to gloss over. If things transpire according to the universe’s own plan, to what extent is our conduct up to us? A thorough-going determinist might press the point further: to what extent are even our opinions, impulses, desires and aversions up to us? The problem of free will emerges, and the Stoic philosopher Chrysippus, for one, argues that our actions are determined, but nevertheless they are our responsibility. Others dilute determinism, supposing that the broad strokes of fate will be drawn regardless, and our own inconsequential actions, though ours to choose, can make no difference to the big picture.

Whatever our view on free will, Marcus joins the Stoics in insisting that our reactions to things are what matter most. Pleasure and pain, health and wealth, power, glory and reputation are all nothing in themselves. Such things only take on a moral flavour when we judge them, when we take it that wealth is good and desirable, something to strive after. So Marcus urges himself to recognise that “opinion is everything”, and by saying this, of course, he means that opinion is nothing out there in the world. It is only our view on the world, and unless we are persuaded by Stoic principles, we can mistake our view of things for the things themselves. We can confuse our perception of harm, for example, when we are passed over for a pay rise, for actual harm. It is seeing an event as harmful rather than as an act of providence beyond our control that makes an event harmful. In reality, Marcus counsels, it is nothing to you. Nothing, in truth, can harm you but your perception of harm.

This is all very well, you might think, but the extra pay would have made a real difference to you: it would have made your life a little better. Maybe you could have afforded some more food and a new pair of shoes. It is clearly something more than “nothing to you”. What is the difference between perceived harm and harm? Whether you perceive it as harmful or not, you are still walking around in uncomfortable shoes. Is the recognition that you have no control over the shoes you can afford, that your shoes are part of a divine plan, really much help when your feet hurt? You can press the point home to yourself by thinking not just of your uncomfortable shoes, but your death.

Marcus and Christianity

Marcus is aware of these lingering worries, particularly the problem presented by death. Part of the attraction of the Meditations is the opportunity it affords to witness someone working through the usual doubts which might trouble a person trying to live by Stoic principles. Marcus is nothing if not an honest thinker.

The Meditations has also been attractive to later Christian scholars, who see in Marcus a pagan struggling towards a view of life which finds full expression in Christian doctrine. Marcus’s conception of providence, his modesty and temperance, his critical attitude towards his own imperfect virtue, his focus on the control of attitudes and desires: all these things are amenable to the “Christian” point of view. Ironically, it is clear that Marcus was no friend of Christianity, and he seems to have had a hand in the persecution and execution of Christians during his rule.

Major works

Meditations is the only work of a philosophical nature written by Marcus Aurelius. It is not entirely clear when the work was undertaken, though references to German campaigns and talk of his approaching death indicate to some that it was written late in his life.

Discourses, transcribed by his student Arrian, is a series of lectures by Epictetus, the Stoic who most influenced Marcus.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments