YouTube conquered the world in the 2010s – where does it go from here?

Ten years ago, YouTubers, vloggers and influencers didn’t exist. Less than a month into the 2020s, these careers are continuing to shape the online entertainment industry. But in the midst of fierce competition, feuds and scandals, what does the future hold for YouTube, asks Sirena Bergman

At the turn of the last decade, YouTube was four years and 10 months old. “YouTuber” wasn’t a word. Neither was “influencer”. There was no such thing as a “beauty guru” or a “daily vlogger”. Viral videos were grainy images of cats play-fighting, cute toddlers whining “Charlie bit me” and Lonely Island parody videos.

When Forbes published a list of the most influential internet celebrities in February 2010, the only YouTuber on it was Shane Dawson, who had been creating videos for around two years. At the time, his channel had 1.2 million subscribers and he was earning $315,000 (£240,000) a year from ad revenue.

He is a perfect illustration of how the platform (and the internet at large) has transformed through the decade. In 2010, Robert J Thompson, founding director of the Bleier Centre for Television and Popular Culture at Syracuse University, told The New York Times that Dawson “is kind of a cross between Ernie Kovacs and the most potty-mouthed kid in the eighth grade”. Now, he’s more likely to be described as the Louis Theroux of YouTube.

In 2010, his content was a mish-mash of dark, problematic, amateur-looking skits, in which he “joked” about murdering the most-subscribed YouTuber of the time, donned blackface and used the N-word, mocked lesbians based on offensive cultural stereotypes and played a vampire drinking menstrual blood. While he was rightfully called out at the time, the criticisms had minimal impact on his career and he continued to win awards (including a Teen Choice gong in 2010) and grow his channel.

Fast forward to the beginning of 2020 and Dawson – who is arguably the only original YouTuber still thriving – has more than 23 million subscribers. He has transformed his brand: self-describing as the “grandfather of YouTube”, he has come out as bisexual, talked about his struggles with eating disorders, pivoted to beauty content and created some of the most viewed videos on the platform. In 2019, he released his most anticipated content yet – an eight-part behind-the-scenes “docu-series” about the creation of an eyeshadow palette with his friend and fellow YouTube heavyweight Jeffree Star. The finale, which was posted on 23 November 2019 and is an hour and 20 minutes long, has been viewed 16.6 million times. The palette itself (without factoring in the additional merch in the line) reportedly earnt him over $10m.

Dawson is but a snapshot of how YouTube has and continues to evolve, and offers an interesting insight into what the future might hold. Without a doubt, YouTube changed the world of entertainment throughout the 2010s. Less than a month into the 2020s, it’s continuing to evolve organically and predicting the trends that other platforms will plan to adopt. Here’s how it happened.

The making of the ‘YouTuber’

The legend goes that YouTube was invented because then-25-year-old Jawed Karim, who worked at PayPal, wanted to re-watch the video of Janet Jackson’s 2004 infamous Superbowl performance in which a “wardrobe malfunction” led to her breast being exposed live on stage. When he couldn’t find the clip online, the idea for a video sharing platform was born, and he recruited two of his PayPal colleagues to create what would eventually become the Google-owned YouTube we know today.

Considering the type of video sharing Karim had in mind, the first post on the platform offers an interesting insight into its consistent ability to either foresee or create trends. The 18-second video is essentially a vlog, in which Karim shows viewers some elephants at the zoo. It was perhaps the earliest instance of a normal person taking a camera and recording an unexceptional snippet of their life. Over the subsequent 15 years, the appetite for this exact type of content would make countless millionaires.

The first YouTuber is believed to be Brooke Brodack. She began posting short comedic skits on the platform in its very early days when she was in her early 20s and gained viral fame. At the time, there was no way for her to make money from her success, but she managed to leverage her popularity to secure a contract to work with Carson Daly on a new project. However, this never materialised, and such opportunities were incredibly few and far between. As a result, there was little financial incentive to post YouTube videos.

In fact, it took YouTube two years to begin allowing people to make money from their videos through their Partner Programme, which meant that YouTube shared a percentage of the ad revenue for videos with affiliated creators.

Their very ordinariness – their relatability – is what makes them so appealing. The ‘girl or boy next door’ who is ‘just like us’ is not an unusual trope in the entertainment world, but on YouTube it’s heightened

But the origin of the YouTuber can be tracked back to the very earliest days of the decade. In 2010, YouTube welcomed two people who would become the biggest household names in this space: Felix Kjellberg and Zoe Sugg, otherwise known as PewDiePie and Zoella respectively. They would go on to lead the charge in the gaming and lifestyle YouTube vlogs over the subsequent decade. That same year, Michelle Phan, who had been posting since 2007, created a “How to Get Lady Gaga’s Eyes” tutorial, which would go viral and turn her into the first ever beauty influencer. Alongside Shane Dawson and Jenna Marbles in the comedy space, these creators would spend the majority of the decade framing what it means to be a YouTuber.

As these personalities began to gain traction, the financial benefit went largely under the radar. Although they were raking in millions collectively in ad money, to their viewers, they were just normal people, and such relatable content had been hitherto nonexistent.

In 2016, Stuart Dredge wrote in The Guardian that: “Their very ordinariness – their relatability – is what makes them so appealing. The ‘girl or boy next door’ who is ‘just like us’ is not an unusual trope in the entertainment world but on YouTube, it’s heightened.”

He went on to highlight the tension this causes as YouTubers increase in popularity: “Staying relatable when you’re earning a high six or even seven-figure annual income is one challenge, albeit hardly unfamiliar from the traditional entertainment world.”

This became particularly apparent as brands began to notice the impact these YouTubers had on consumer habits. As soon as PewDiePie shared an unknown independent video game, or Zoella talked about her favourite concealer, the Oprah effect would lead to a huge boost in sales for the products. As a result, commercial partnerships became a key element in monetising YouTube popularity, and the “influencer” was born.

The year 2010 was pivotal in the creation of YouTuber culture for two other reasons. Firstly, it was the year VidCon, the annual YouTube convention, launched. It played on the fandom that was beginning to emerge, and offered viewers the opportunity to meet their favourite creators in person.

The following year Andrew Wallenstein identified the early signs of influencer culture at VidCon. He wrote for Variety: “These YouTube phenoms aren’t to be confused with viral videos, which are typically one-off sensations. With a sophisticated understanding of the YouTube platform, these talents manage to bring viewers back again and again. And this isn’t the largely passive experience of TV; YouTubers are engaged in an interactive loop grounded in social media.”

These YouTube phenoms aren’t to be confused with viral videos, which are typically one-off sensations. With a sophisticated understanding of the YouTube platform, these talents manage to bring viewers back again and again

He also preempted the trend for young people beginning to see YouTube as a potential career, saying: “They’re not just here for hero worship. Many VidCon attendees split their time between paying homage and paying attention to training sessions and peers who can educate them on everything from proper lighting to balancing their production responsibilities with homework.”

The second crucial factor of 2010 was the launch of Gleam Futures, a UK-based talent agency which spotted the earning potential of YouTubers in the early days and signed Zoella, along with a number of similar YouTubers, who became known as “the Brit Crew” – including Tanya Burr, Alfie Deyes and Niomi Smart. Gleam’s founder Dominic Smales led the charge on negotiating brand partnerships and collaborations for YouTubers, as well as carefully managing their public image.

And for a while, it worked, catapulting the Brit Crew into almost overnight success, fame and wealth. But towards the latter end of the decade, as advertising regulators cracked down on influencers and consumers began to demand more transparency, it became almost impossible for YouTubers to maintain the veneer of relatability and authenticity, and the inevitable backlash began.

As different influencers and online communities have been hit with criticism and controversy, they have responded by pivoting in different directions.

Michelle Phan left YouTube entirely in 2016, returning in 2019 after launching her own makeup brand. Sugg meanwhile, after a two-year stream of drama including an overpriced advent calendar, the resurfacing of unearthed homophobic tweets and the revelation that she used a ghostwriter for her novels, abandoned her Zoella brand and stopped posting entirely on her main channel, focusing instead on vlogging and working on other ventures (in 2019 she launched two photo and video editing apps). PewDiePie, after being blacklisted by advertisers following allegations of racism and white supremacy, now makes commentary videos about the drama going on in the YouTube community – most famously being one of the only people to side with James Charles when his feud with Tati Westbrook first kicked off.

Meanwhile, some YouTube creators have focused on other platforms, such as IGTV, Instagram’s short-form vertical video platform that launched in June 2018 and has become a popular space for beauty and lifestyle influencers (such as Tanya Burr, who no longer posts on YouTube at all) and Amazon-owned Twitch, which is the main space for livestreaming gaming content (and which Google unsuccessfully tried to acquire in 2014).

With this in mind, the future of the YouTuber looks worrying, but some people argue that as more and more platforms emerge, influencers will look back to YouTube for its simplicity and the freedom it offers

Alessandro Bogliari is the CEO of The Influencer Marketing Factory. He says: “YouTubers still have a great tool to talk in front of people for how many minutes they want and almost about everything and create a great connection with their viewers. To be still relatable on YouTube users will look for more quality in terms of storytelling, shooting settings and more transparency in terms of brand deals and their real life to fight the flexing [boasting] mindset that is typical for example on Instagram.”

This desire to return to the roots of YouTubers as “normal people” could pave the way for a different type of influencer to shine.

Megan DeGruttola is the head of global content marketing and communications at Stackla, a social content marketing platform. She recently wrote that: “The influencer industry is undergoing a major shift towards not just micro-influencers, but organic influencers.”

Many VidCon attendees split their time between paying homage and paying attention to training sessions and peers who can educate them on everything from proper lighting to balancing their production responsibilities with homework

“Organic influencers are the real people who already buy your products and services and create content about your brand – they’re your genuine brand advocates. They may have 5,000 Instagram followers, or they may have 50, but the size of their social followings aren’t as important as their passion, authenticity and collective influence.”

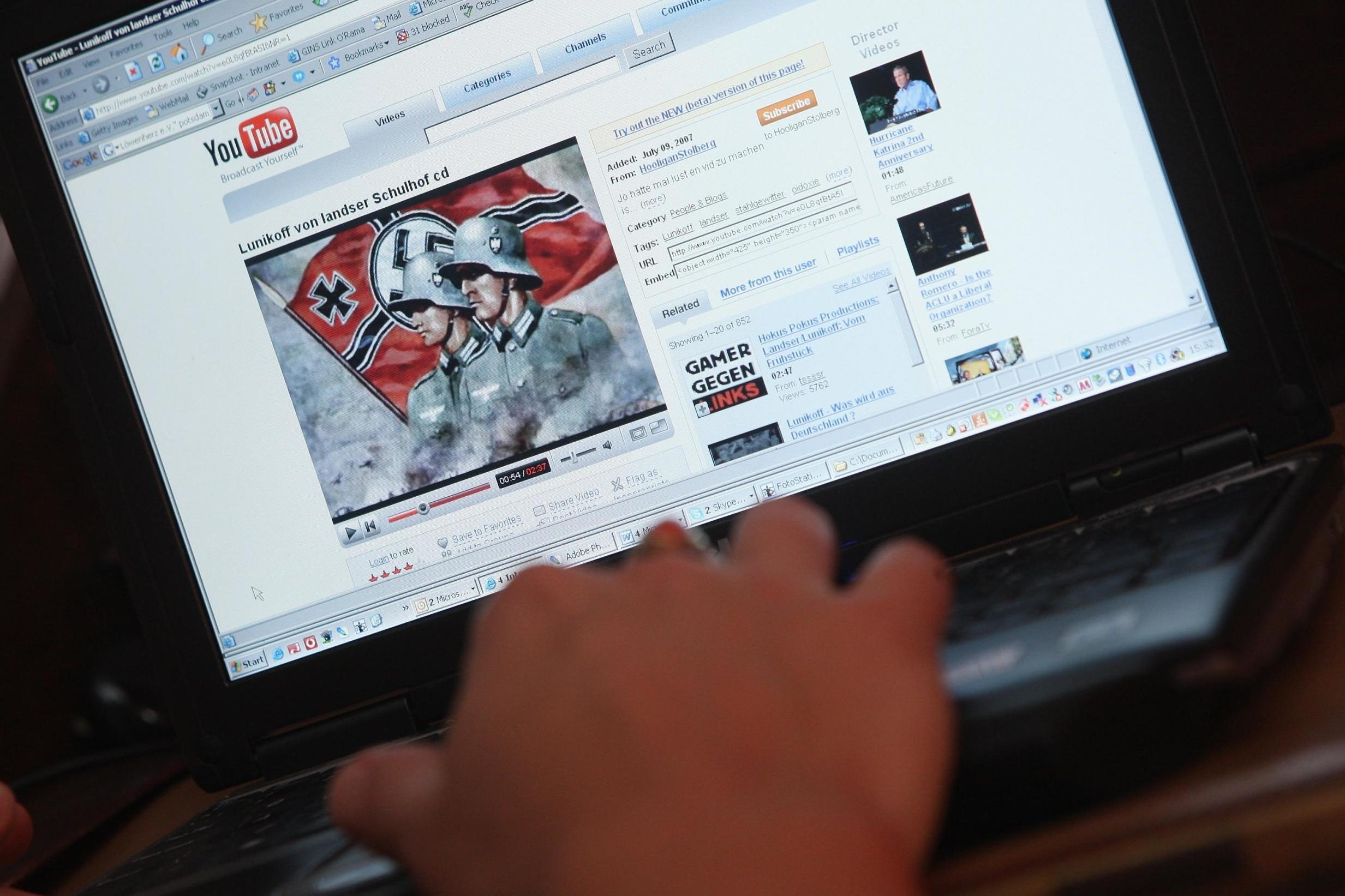

But YouTube has become a lot less democratic than it once was. After an investigation found that hundreds of major brands had ads running alongside videos promoting white nationalists, Nazis, paedophilia, conspiracy theories and North Korean propaganda, the platform quickly began changing the way it assigned ads, leaving many smaller creators “demonetised”. At the same time, the algorithm boosts the most viewed content (although engagements and watch time also factor in), so it’s hard to see how smaller creators will fare. Back when the likes of PewDiePie and Zoella started out, the environment was very different.

Speaking to The New Yorker, co-founder Chen explained that in the early days he would often highlight videos which the algorithm would miss, such as amateur footage of the destruction wrought by Hurricane Katrina, or documentation of a racist attack at a bus stop in Hong Kong.

Now, with so much content out there, YouTube largely relies on algorithms and AI to work out what viewers want to see, which can make it incredibly difficult for an unknown creator to rise to the top.

The quiet successes of YouTube

While influencers tend to dominate the conversation around YouTube, it’s important to bear in mind the platform’s hugely successful streaming services.

Since its launch in 2009, Vevo – which posts official music videos to YouTube – has brought in hundreds of millions of views. Ariana Grande’s “thank u next” video broke records with 59 million views in 24 hours, while Taylor Swift’s “ME!” surpassed it with 65 million last year. It has now had almost 300 million views – figures that blow any influencer out the water. Swift’s Vevo channel alone has over 18 billion views.

Music has always been a big driver in YouTube’s success. In December 2012, “Gangnam Style” became the first YouTube video ever to reach 1 billion views, just five months after it was posted. And last May, T-Series, a Bollywood music label, became the first YouTube channel to hit 100 million subscribers, beating PewDiePie – the biggest YouTuber.

YouTube has offered a TV and movie rental service since 2011, but in 2017 launched YouTube TV, which has been called the “best live TV streaming service”. At $50 a month, it’s pricier than Netflix and Hulu, but has found a market in high-income millennials less likely to own a TV while wanting to watch live entertainment.

While it doesn’t appear to be profitable yet, there is a clear path to its success. Writer Adam Levy explained: “In case you didn’t know, YouTube’s parent company is a pretty big advertising company. YouTube TV is an opportunity for Google to move deeper into television advertising. It might even be able to make deals to manage inventory on some of the smaller networks on its service. Ultimately, the company expects to generate $15 to $16 per subscriber in ad revenue per month, according to The Information’s source. That kind of ad revenue will more than cover YouTube TV’s shortfall on programming expenses from subscriber revenue at $50 per month.”

In the past two years Youtube has also launched YouTube Premium, which is intended to combat the loss of revenue due to ad blockers and offers exclusive ad-free content to subscribers, and YouTube Music to rival Spotify, which had 15 million subscribers in May 2010, just a year after its launch.

By continuing to diversify, YouTube can build on the success of the past decade, which saw it shape the way millennials consume entertainment content, and become a one-stop-shop for all our influencer, TV and music needs. But ultimately, it’s cultural relevance will always lie with the personalities it manages to elevate to celebrity status.

The future of YouTubers

Back in 2011, Kevin Allocca, YouTube’s head of culture and trends, gave a TED talk in which he spoke about what makes a video go viral. At the time, he mentioned viral sensations such as Rebecca Black’s “Friday”, a video of a double rainbow and “Nyan Cat”. However, in 2020, the landscape is very different.

One of the most anticipated drops among viewers is the next Shane Dawson documentary. It has yet to be announced or teased, yet millions of subscribers send comments and tweets on a daily basis begging for any crumb of information about what he might release next. These aren’t the comedy skits of early 2010s Dawson, but long-form deep-dives into the issues YouTube viewers are interested in, such as what’s really going on with Jake Paul, the truth behind the disastrous YouTube convention TanaCon or why YouTuber Eugenia Cooney disappeared from the platform. Similarly Marlena Stell, one of the first beauty YouTubers to leverage her success and turn it into her own brand Makeup Geek, has abandoned tutorials and product reviews in favour of a series of long-form reality-style documentaries called Beauty And The Boss.

As smaller YouTubers focus on relatability and the big players look to more polished, in-depth content, another space which continues to thrive is the drama channel community, which functions as a self-regulator holding YouTubers to account and commenting, gossiping and speculating about the biggest players in the space.

Drama channels began to emerge around four years ago, but have exploded as a content stream in the past year. During the great cancellation of James Charles last year, the drama community thrived like never before, offering a breathless running commentary of the scandal, which became one of the biggest in YouTube’s history. Now, it’s one of the easiest ways to gain traction fast, as viewers hungrily search for all and any content relating to whichever drama is trending that week, from problematic product launches to relationship breakups.

Perhaps more encouragingly, YouTube also continues to be a space for social change. In 2010, activist Dan Savage launched the It Gets Better Project on YouTube, sending messages of hope to LGBT+ teenagers. The campaign was so successful that even then-president Barack Obama participated. YouTube also played an instrumental role in the Arab Spring, with people uploading videos of the protests which went viral and led to their mainstream coverage.

But 2020 has taken this to a new level, with the most talked-about video so far being from NikkieTutorials – a Dutch beauty guru with 13 million subscribers who has been uploading since 2011 – entitled “I’m Coming Out”, in which she revealed that she is transgender. The announcement shook the community, which has never before had a big name come out as trans after years of keeping it private. In fact, this has never really happened in any cultural space. The narrative around her revelation has been hugely positive, and her ability to tell the story to her audience in her own words is inextricably attached to her platform as a YouTuber.

If these trends are anything to go by, the future of influencers in 2020 is a far cry from what it was 10 years ago. Gone are the days of listing your favourite makeup products in your bedroom or making three-minute skits. Now influencers looking to stay relevant will likely need to focus on high quality, long-form creative content, meta-commentary about the platform itself, or identity-focused causes which entice Gen Z-ers who are fast pivoting towards platforms such as TikTok, leaving the millennial spaces behind.

In its 15-year history, YouTube has always been ahead of the curve in creating content people truly want to watch, largely thanks to its lack of gatekeepers and user-driven momentum. If it can continue to allow the space to be democratic, and find a way to let smaller, more innovative creators thrive, the 2020s could be its best decade yet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments