‘I will never be able to forget what I saw’: The young Afghans fighting for their country’s soul

Peace talks between the government and the Taliban started in September, giving Afghans hope that an end to the violence is in sight. Natasha Phillips speaks to the young people on the front lines of the movement

Sitting in a quiet, softly lit kitchen in Chicago, Safia, who turned 18 in September, is describing the first time she saw a man being decapitated.

“Seeing a person dying in front of you that you can’t help was the most difficult part for me. You could see in his eyes he had lost any hope that someone would stop the attack,” she says, letting her shoulders drop.

The beheading happened last summer in Afghanistan, and though it is fresh in Safia’s mind, she is recalling the gruesome event with a hard-fought numbness found only in children exposed to routine violence and loss.

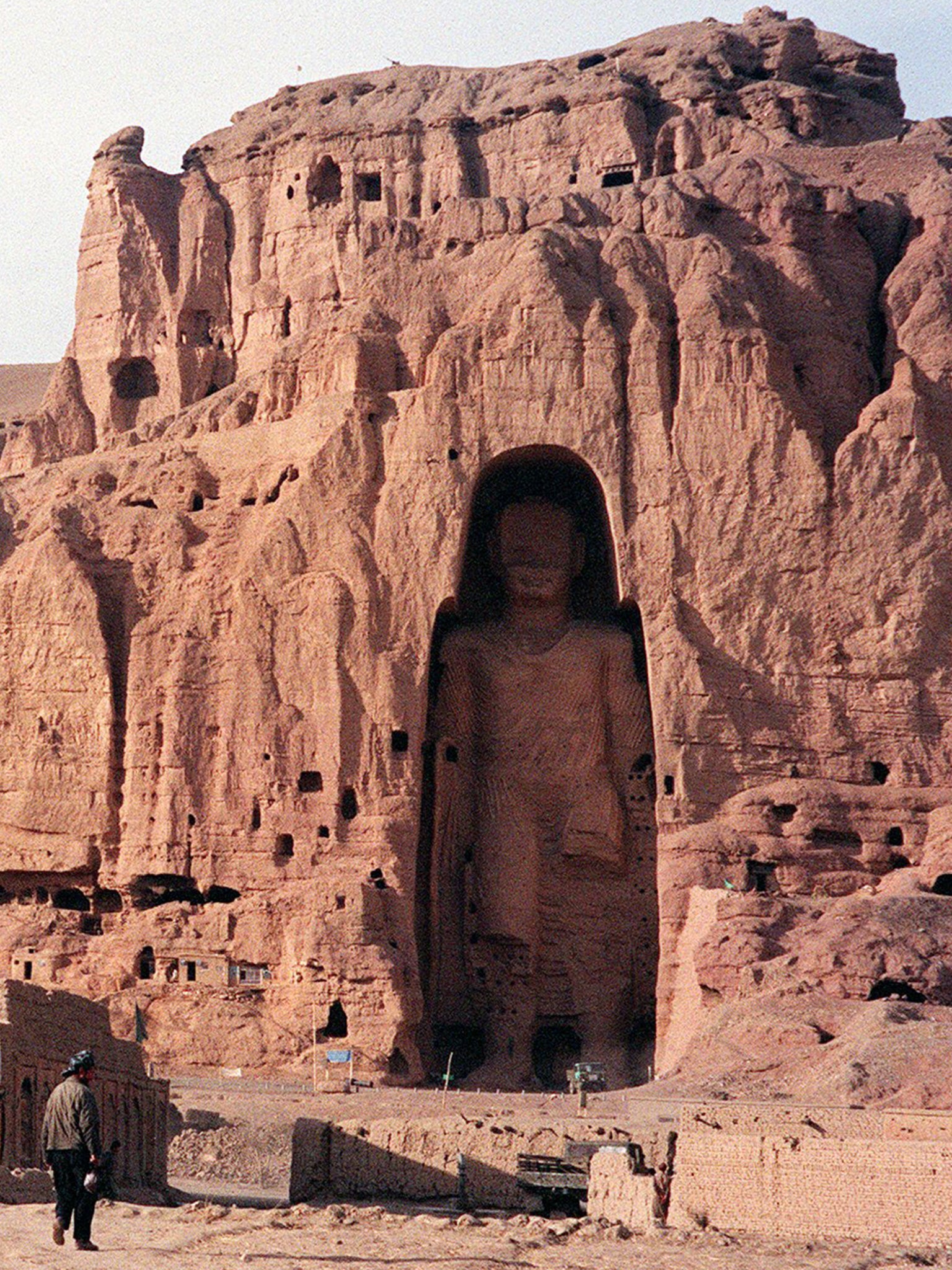

The man had been travelling with her in a cohort of minibuses on their way to Bamiyan, an area of otherworldly beauty in Afghanistan home to two giant buddhas carved into the mountains before being destroyed by the Taliban during the Afghan war.

Safia had asked her mother if they could visit the province after hearing stories from friends about scented valleys holding Buddhist sanctuaries and gravity-defying Islamic structures. She had convinced her mother by telling her she was anxious about her United States visa being approved. If the application was successful, it would enable her to leave Afghanistan and take up the scholarship she had been offered at the Woodlands Academy of the Sacred Heart in Chicago. The trip, Safia said, would soothe her nerves.

As the minibuses came round a bend, Safia could see a Taliban checkpoint ahead, and the buses were asked to stop. Her bus jolted alive with the low chatter of people on board who seemed to know why they were being checked.

The Taliban were looking for a man who had been a member of the Afghan army, one passenger said, and they had received information he was travelling today, as well as details about the man’s physical appearance and clothing.

As Safia looked on from inside her minibus, she could see the man being dragged from a separate coach by a member of the Taliban and made to stand at the side of the road, which was a long dirt track dotted with shops. Then his head was cut off.

“I will never be able to forget what I saw,” Safia says. “I’m more afraid of the gunmen than I am of death.”

Afghanistan’s government and the Taliban have been locked in a violent standoff for almost two decades, fighting over territory, political ideals and religious rule.

The Taliban, a Sunni Islamic political movement led by Mullah Baradar Akhund, wants Afghanistan to be governed under Islamic law, which the group says would not discriminate against non-Muslims. The current government, led by president Ashraf Ghani, wants an Islamic democracy that represents the five or more different religious denominations and 14 ethnic groups living inside the country.

In a breakthrough for the conflict, the first ever peace talks between the government and the Taliban were launched in September in Doha, giving people in Afghanistan hope that an end to the suicide bombings and mass shootings was in sight.

But despite a call for an immediate ceasefire from the head of Afghanistan's Peace Council, Abdullah Abdullah, which he said was needed before any meaningful talks could take place, attacks in Afghanistan continue to scar the country.

A suicide bomb which detonated near an education centre in a Shia neighbourhood in Afghanistan’s capital city, Kabul, on 24 October left at least 18 people dead and 57 injured, including children, while an attack on Kabul University on 2 November left 22 dead, 16 of whom were students, and injured a further 22 caught in the blast.

In October alone, an additional 27 attacks in the country were reported by TOLO News, Afghanistan’s 24-hour media network, killing a total of 243 people and leaving 339 injured.

Islamic State-affiliated gunmen and the Taliban have claimed responsibility for individual attacks, although the Taliban has been quick to deny any involvement with the terror attacks taking place during the peace talks.

Separating the actions of the Taliban and Islamic State though, may not be so straightforward. According to Dr Sajjan Gohel, the international security director at the Asia-Pacific Foundation in Vancouver, there is evidence which suggests both groups are working together to carry out these attacks, often through the subdivisions which exist in each faction.

During meetings with law enforcement officers, security agents and military officials stationed outside Afghanistan in May, Dr Gohel and his team concluded that the Taliban had admitted several of the largest terror attacks had involved cooperation between a branch of Islamic State based in Pakistan, and the Taliban’s own Haqqani network.

There is no strategy from our government or the international community for the protection of the youth, specifically young peace builders and community leaders

While the extent of these collaborations is unknown, what is clear is that the conflict has taken the lives of tens of thousands of Afghans, many of them children and young people.

Making up more than two-thirds of Afghanistan’s population, children and young people in the country are disproportionately affected by the violence. Afghanistan is second only to the African content for having the world’s youngest population, with approximately 48 per cent of Afghans under the age of 15, and almost 75 per cent of the population under 29.

Data collected by Afghanistan’s government estimates that more than 12,500 children (those 18 and under), were killed or injured in the violence between 2015 and 2018, while 274 children were recruited for combat or “fight support” roles in the country. Further research found that one-third of children in Afghanistan had experienced psychological distress related to the loss of a family member and the constant risk of death or injury from terror attacks in schools.

Frustrated by the violence and the painfully slow progress of the peace talks in Doha between the government and the Taliban, young people in Afghanistan are taking the business of peace into their own hands.

The National Youth Consensus for Peace (NYCP), launched in June by its founder Yahya Qanie, 26, is a growing movement sprawling across Afghanistan. The organisation incorporates 244 youth-led organisations, and has more than 2,000 young people from 34 provinces around the country working to secure a stake in the peace talks, and bring an end to the conflict.

Yahya began peace building in 2014, first working as a volunteer with a movement to empower youth and women. He went on to found Kabul’s Model United Nations General Assembly, and then became president of the United Nations Association of Afghanistan, before establishing the National Youth Consensus for Peace, a movement which he says is truly egalitarian because it has no one leader.

Furthermore, the members of the NYCP are all volunteers, paying for peace building work they undertake out of their own pockets. Yahya says young people are fundamental to the peace process in Afghanistan because they are going to inherit the legacy of any peace deal made. As such, he believes their voices are a fundamental part of the peace process, which should be heard and protected.

“There is no strategy from our government or the international community for the protection of the youth, specifically young peace builders and community leaders,” he explains, adding, “about 10,000 people are affected by attacks every year, and of those 8,000 are young people including Taliban youth, all being wounded and killed from gunfire by Taliban and security forces.”

Yahya sees a disconnect in the engagement of young people aged 18 to 35 inside the country, who he says make up around 90 per cent of Afghanistan’s security forces, and the government’s willingness to consider their vision for a peaceful and prosperous Afghanistan. “If the youth are being killed while fighting for peace, why is there no space for us to talk about peace and share our opinions?” He says.

Similarly dissatisfied with the government’s proposals for peace, the NYCP created its own manifesto, which it launched on 12 August to coincide with the United Nations’ International Youth Day at the movement’s first ever event, in Kabul.

The resolution outlines the NYCP’s concerns about the current peace process – which it alleges is not impartial – and offers recommendations for lasting peace in Afghanistan. The document also urges the government to acknowledge that youth engagement in the peace process at all levels is a fundamental right which young people should be granted.

In addition to the requests aimed at the current government, the resolution asks the Taliban to uphold the second chapter in Afghanistan’s Constitution, which contains a list of rights and freedoms Afghan citizens are entitled to. Those rights include freedom from discrimination and persecution, freedom of expression, gender equality and the peoples’ right to elect their own government.

Hopeful and innovative, the resolution is also cautious, authored as it is by a demographic familiar with the fragile nature of peace in Afghanistan. Addressing the international community, the document asks world states to act as watchdogs during the peace talks, and to continue providing support and protection to Afghanistan’s people after a deal has been reached.

Since its publication, the NYCP has shared the resolution with the UK embassy, the US embassy, the German embassy, Nato and the EU.

And in an effort to engage the Taliban, a soft version of the resolution was sent to Taliban spokesperson Suhail Shaheen on 19 August, via WhatsApp. The texts, and the resolution, elicited a response from Shaheen, who offered to speak with the NYCP. That meeting fell through after an NYCP member contacted Shaheen to launch the online conference. Shaheen said an emergency had come up and he would no longer be able to speak.

Peace building in Afghanistan is a treacherous calling, and one that frequently causes Yahya’s family to plead with him to stop.

“What we are doing is very dangerous, because young people have no protection. Whenever I leave the house, my parents ask me whether I really have to do this peace building work, and they advise me to leave all these things behind. On one occasion I went to Europe, and 25 of my relatives called me and begged me to stay and not come back to Afghanistan, but I didn’t listen,” he says.

Yahya is part of a wider collective of young people who have chosen to stay in Afghanistan after being offered opportunities abroad. They see their engagement in the peace process and their physical presence inside the country as a duty they owe to Afghanistan, and its future.

Breshna Musazai, 31, known as “Afghanistan’s Malala” after being shot three times by the Taliban in 2016 and then going on to graduate with honours from the American University in Kabul, is part of this group who have chosen to stay in Afghanistan and work on the peace process.

“I had been attending evening prayers at the mosque with a friend, when we heard gunshots followed by an explosion,” Breshna says.

Breshna, who has polio in her right leg, was unable to run, and decided to go through a nearby building with several floors, thinking it would be safer than crossing the exposed garden and outside areas of the mosque.

The first bullet went into her left leg. Thinking fast, she dropped to the ground and played dead. The gunman shot her again

As she approached the entrance to the building, she noticed broken glass on the floor. The attack had left her without any time to put her shoes back on after prayers, giving her no choice but to walk across the glass in her bare feet. The slow journey across the jagged shards was excruciating. Entering the building, she recognised several of the girls hiding inside. They had all been with her in the mosque.

One girl was trying to help another make her way into the room through an elevated window, which was partially broken. As she tried to pull the girl into the room, the window frame dislocated completely and fell, hitting the girl below, slicing her nose and cheek. The cuts were deep, and Breshna reached into her bag to give the girl a tissue. Then Breshna heard someone behind her.

As she turned around, she saw a man with a gun wearing a security guard’s uniform. Breshna breathed a sigh of relief, and the man shot her. The Taliban had dressed as security guards that evening, to avoid being detected by local law enforcement.

The first bullet went into her left leg. Thinking fast, she dropped to the ground and played dead. The gunman shot her again, and she felt the second bullet hit her left foot.

The girls in the room ran as fast as they could, away from the shooter, while Breshna lay motionless on the floor. Too scared to scream, or move, she wondered whether the gunman would shoot her in the head to make sure she was dead, but he disappeared, and left her alone.

As night drew in, she could see her phone pulsing with light as family members called one by one to reach her. Breshna had switched her phone onto silent in the mosque and had forgotten to turn the sound back on, an oversight she was grateful for as she tried to plan her escape. She heard the sound of whispering in the corridor.

Rounds of bullets made their way over her head, increasing in intensity from either side of the room, as the Taliban and Afghan police opened fire on each other. The bullets flew over her in waves, and it was at that moment Breshna thought she would die.

A third bullet hit her left leg, and the gunfire began to ease, eventually trickling to a standstill. She picked up her phone and texted her parents. They told her the police had arrived and would come to get her. As she approached the ambulance waiting for her outside, slumped over the shoulder of a policeman, she moaned as her broken leg bumped against his back. The policeman told her to stop making a noise — the Taliban would hear her and they would both be killed.

Breshna’s ordeal lasted six hours, and took a toll not just on her body but on her mental health as well, leaving her fearful for months after the attack. She also wished she had known about the Taliban’s strategy when they carried out a terror attack.

“After the attack, my father told me that when terrorists decide to target a place, they look for the tallest buildings to enter, so they can go to the top of it and get the best view for fighting. I wish I had known that before, I would never have gone into this building, I would have chosen a much smaller building with fewer floors instead,” she says.

Despite her experience, like Yahya and Safia, Breshna feels compelled to secure a peaceful future for Afghanistan. She is also a member of the NYCP and is critical of the power base at the talks.

For Breshna, and the NYCP, the negotiations between the Taliban and the government appear to be more about political control than delivering long-lasting peace.

“They started the war in the name of religion, but this is a political war, it is not about Islam. Peace will never come if they keep fighting,” Breshna says.

Terrorists want media coverage, but today an attack can’t compete with things like the presidential election, so they launch bigger and bigger attacks

Beyond concerns about a power struggle between the government and the Taliban, the NYCP has been left with the feeling that the government may not be interested in genuine dialogue with Afghanistan’s youth.

“Our goal and purpose at the consensus is to have someone at the peace talks who is independent of the government, but I don’t think the government is interested in that goal. From the meetings we had with government officials, they were not supportive,” she says.

The government’s stance on youth inclusion, and the peace talks, contrast with the criticisms levelled at it by the NYCP and its members. President Ghani has talked about the role of youth in the peace talks, reiterating the need to include young people as a peace deal would have a far-reaching impact on their futures.

In line with this policy, Ghani’s government selected two young men to represent the youth in Afghanistan, Khalid Noor and Batur Dostum, who are now part of the negotiation team in Doha.

The NYCP says it is concerned about the selection because Khalid and Batur are sons of prominent warlords who hold powerful positions.

Khalid’s father, Atta Mohammad Noor, is the chief executive of Jamaat-E-Islami, a Muslim political party in Afghanistan. Batur’s father, Abdul Rashid Dostum, served as vice president of Afghanistan from 2014 to 2020, and has since been promoted to marshal by the president as part of a series of concessions made by Ghani to secure a power-sharing deal with his political opponent Abdullah Abdullah.

Yahya feels strongly about Khalid and Batur representing young people in Afghanistan at the peace talks.

“The youth representatives in the negotiating team in Doha are not representative of the youth, but of political parties, sons of war lords. They have never lived in Afghanistan, they don’t know what is happening on the ground and they don’t know what to discuss at these meetings because they haven’t been in touch with Afghanistan’s youth,” he says.

Others are more optimistic about the negotiations.

Farid Haqiar has worked for President Ghani for more than three years, and has held several different positions in government, including a stretch from June 2018 to June 2020 as the general director of complaints at Arg, the Presidential Palace.

Farid now works at the government-owned energy company Da Afghanistan Breshna Sherkat, where he is the director of monitoring and evaluation. “In my opinion, the peace process is developing. We have hope, as long as this very slow process leads to peace,” he says.

Describing his time as general director of the complaints department, Farid is explaining that members of the public and young people never lodged grievances with the palace. Instead, he found himself processing complaints from government officials. He says officials would call up regularly to lodge objections about the Taliban and ask him to shut off the electricity to their villages, a request which Farid says he would always decline.

While there have been several peace agreements in the last few years, they have all failed because they did not include the community

Discussing the recent focus by opposition groups to target schools and other venues which attract children, Farid says the choice may be down to publicity.

“I think it’s related to their goal to get media attention. Terrorists want media coverage, but today an attack can’t compete with things like the presidential election, so they launch bigger and bigger attacks,” he says.

“Even the latest attack at Kabul University didn’t get any airtime through our national media outlets, which chose to cover the terror attack in Austria this month instead. It’s as if one Austrian life is worth more than the lives of 80 young Afghans,” he says.

The attack, which took place in the Austrian capital Vienna on 2 November, left four people dead, including a young man, and 22 people injured. The gunman was identified as a 20-year-old Islamist, who had spent time in prison for terror-related offences.

Though terror attacks rage on in Afghanistan, Farid believes that the peace talks will bring an end to the conflict. “I know the president’s main concern is that the voice of the 37 million Afghans in the country are heard, at least as much as the voice of all other stakeholders,” he says.

For now, the NYCP remains unconvinced that the government wants to give young people in Afghanistan a legitimate place at the negotiation table. “The government is just telling the world that they are engaging with the voices of the youth but in reality it’s just for show, they’re not really listening to us,” Breshna says.

Safia shares Breshna’s concerns, adding that the peace talks are unlikely to end any time soon. “The peace talks are a waste of time because the government already knows the Taliban is not going to give up until they get what they want, which is that Afghanistan should be their country, and under their control,” she says.

For young Afghans invested in the peace process, education and political change go hand in hand. It is customary for families across the country to invest heavily in their children’s education, often going without to ensure their sons and daughters can attend school, and university.

“I come from a family which before me did not have access to education, but my parents were determined that I should go to school so that I could defend myself. Being able to read and write has given me power,” Safia says.

That power is often harnessed through international scholarships to elite colleges. Breshna, whose parents had been struggling to fund her education, went on to win a scholarship to study law at the American University in Kabul.

And after winning a scholarship to the Woodlands Academy of the Sacred Heart in Chicago, Safia is now a finalist for the Fulbright scholarship programme.

Tom Valenti, a Chicago-based lawyer and mediator specialising in conflict resolution, who co-founded the Global Youth Development Initiative (GYDI), a project which connects Afghan students with professional mentors around the world, helped Safia apply for her scholarships through the project. He also worked with the GYDI’s two other founders, Gharsanay Ibnul-Ameen and Sana Ahmadi, to help them secure Fulbright scholarships, which both women have since completed.

As part of the GYDI’s work, Tom arranges online sessions for young people to talk about their experiences of terror attacks, which allows students to explore their feelings in a safe space, with other young people who understand the pain and trauma of a life lived in violence.

By the time Afghan children reach their teens, Tom says, they become immune to the devastation they’ve seen and find their own ways to process the grief.

“Their experiences all include witnessing violence at close range, so this is their reality. In Afghanistan, apart from deaths due to violence, when a person dies, people go to the tomb to see the body, and pictures are shared. With regard to violence the culture persists, and young people have taken to posting photos of friends and family killed in attacks, online. It doesn’t matter that the pictures are graphic, young people need these images to document the deaths,” he says.

From making sense of their grief to powering peace talks, young people in Afghanistan are not letting anything stand in the way of their vision for a conflict-free homeland.

“Youth by definition embraces hope, innovation and energy, and while there have been several peace agreements in the last few years, they have all failed because they did not include the community, women, children and the older youth,” Yahya says.

Breshna agrees that inclusion is the key to any lasting peace in Afghanistan, and can only see that happening once the violence stops, saying: “A ceasefire should be the first priority for these parties if they want peace. It’s incredibly important. Without it, there is no evidence that the Taliban is committed to peace in Afghanistan.”

Safia thinks the government should focus on integrating the Taliban into the wider community as a first step.

“I don’t believe the conflict is the Taliban’s fault, because every member starts out life in a Taliban family and there is no violence between them. And so children watch their parents hurting other families, and they think this is how life should be. They grow up in a world where they are told you should kill, that instead of praying you should carry a gun, instead of respecting women, you should hurt women. I don’t think Islam condones hurting others.”

For now, Safia is content setting her sights on further education, and jumping out of aeroplanes at her local skydiving centre as she contemplates her future. Excusing herself from the table, she explains she has agreed to meet a friend for ice cream, on what is an unusually warm November afternoon in Illinois.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments