How Yom Kippur highlights the masochistic nature of Jewish tradition

Zoe Ettinger reflects on finding a sense of community in the repentant traditions of her least favourite holiday

As a young Jew, I never looked forward to Yom Kippur. Known cheerily as the Day of Atonement, it’s one of the High Holy Days and is considered the most important day of the year in the Jewish calendar.

Famously, American baseball legend Sandy Koufax made headlines when he refused to pitch in the first game of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur. He was replaced by Don Drysdale, who, when taken out of the game for poor performance, told the Dodger’s manager, “I bet you wish I was Jewish, too.”

Yet a lot of non-Jews mistakenly think that Hanukah is the most significant Jewish holiday, since it falls around the same time as Christmas. I discovered as a child that all the gift-giving at Hanukah was really just a ploy to keep up with Christmas, a fruitless endeavour.

While Christians are feasting on roast beast and tearing open presents from Father Christmas on their most important holiday, we Jews have a day of fasting and admitting everything bad we’ve done throughout the year, celebrating the great Jewish tradition of masochism.

The whole Yom Kippur holiday lasts for a 25-hour period, in which we attend five prayer services: Kol Nidre (the evening service that marks the beginning of the holiday) Shacharit (early morning service with the Torah reading); Musaf (second morning service with a torah reading); Mincha (afternoon service with the Torah reading); and Ne’ilah (final service).

With our history of persecution, you’d think we’d suffered enough, but every Yom Kippur, as I spend hours contemplating a year’s worth of sins, I’m reminded that we’re not done yet.

Growing up, my parents would drag my brothers and me to our temple in upstate New York, where we’d spend what felt like years listening to our rabbi recount the Hebrew prayers, sitting on the red velvet seats in a starvation-induced stupor.

The only “fun” part I remembered about the service was when the rabbi would blow the shofar, a large ram horn, as hard as he could, which would produce a noise like a broken tuba. The final blowing of the shofar also signals the end of the fast, so I liked it for that reason too.

The majority of the service is spent listening to the prayers and singing along with the rest of the congregation, recounting our sins. I don’t want to hear my own sins out loud, much less those of others. It’s like watching people regurgitate – their life experience, that is, not their lunch.

If you’ve ever heard of the self-deprecating nature of Jews, know that we have been trained by this week of repentance. It is in this masochistic tradition of fasting and headache-inducing prayer that we somehow grow closer to God

My family and I are Reform Jews, so for us, this is a temple marathon. Reform Jews are the least devout, after Conservative and then Orthodox, considered the most devout.

Some Orthodox Jews have an interesting Yom Kippur tradition known as Kapparot. On the afternoon before Yom Kippur, they wave a chicken over their heads and ask for forgiveness. For men, a rooster, and women, a hen. The chicken symbolises their atonement, and it is slaughtered afterwards. Whether the chicken or the Jew came first, no one knows.

Reform Jews are not exactly respected by the Orthodox community. In 2017, the former chief rabbi of Israel called Reform Jews worse than Holocaust deniers. This interreligious prejudice can best be expressed through a classic Jewish joke:

(A mezuzah, for all gentiles out there, is a piece of the Torah we place in all doorways.)

A man seeking religious advice walks into an Orthodox rabbis office.

Man: “Rabbi, I recently purchased a Maserati, and I was wondering if I could place a Mezuzah on its door.”

Orthodox rabbi: “What’s a Maserati?”

Man: “An Italian sports car.”

Rabbi: “Hmmm, I would ask a Conservative rabbi, he may know better…”

Man with Conservative rabbi:

Man: “I was wondering if I could place a Mezuzah on my Maserati.”

Rabbi: “What’s a Maserati?”

Man: “An Italian sports car.”

Conservative rabbi: “Ask a Reformed rabbi, he should know.”

Man with Reformed rabbi:

Man: “I was wondering if I could place a mezuzah on my Maserati.”

While Christians are feasting on roast beast and tearing open presents from Father Christmas on their most important holiday, we Jews have a day of fasting and admitting everything bad we’ve done throughout the year, celebrating the great Jewish tradition of masochism

Reformed rabbi: “I don’t see why not… but what’s a Mezuzah?”

So you can see that we Reformed Jews are not considered to be particularly knowledgeable about our religion. But for the High Holy Days, which includes Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, every Jew who’s any Jew attends temple.

However, it should be noted that you can’t just walk into a temple off the street on High Holy Days. You need tickets, which are sometimes sold months in advance. Why buy tickets for sporting events or gigs when you can buy one to atone?

There’s even an episode of Larry David’s Curb Your Enthusiasm about getting tickets for Yom Kippur. Larry forgets to buy tickets, and so he attempts to buy scalped ones for the service. Mid-service, a police officer comes into the aisle to check his tickets and, finding them fake, kicks him out. If you’ve ever been to a High Holy Day service, you know this is just another day at temple.

I remember at one such service, attendance was so high they had to fill the basement with seats, where there was a screen projecting the service upstairs. If you didn’t feel like a sinner before, spending a day sitting in a damp room that smelt of stale apple juice certainly did the trick.

The first High Holy Day we attend, Rosh Hashanah, precedes Yom Kippur by nine days. On Rosh Hashanah, God inscribes each person’s fate for the coming year into the Book of Life, and on Yom Kippur, that fate is sealed.

It is in these nine days between the two holidays that you are meant to amend your behaviour and seek forgiveness, performing “teshuvah” or repentance. Basically, you have about a week to get your affairs in order to get into God’s good graces.

If you’ve ever heard of the self-deprecating nature of Jews, know that we have been trained by this week of repentance. It is in this masochistic tradition of fasting and headache-inducing prayer that we somehow grow closer to God.

Ever since Abraham, we Jews have been masochists. In the Torah, Abraham pleads with God to save the evil city of Sodom. He asks how many righteous citizens he would need to find for God to spare the city. God responds, asking him to sacrifice his own son, Isaac, and Abraham does so without question. God winds up sparing his son, but not because Abraham asked him to. He was willing to suffer in the name of his religion.

It was only through this extended period of suffering that I was able to learn something new about myself. It made me realise why people want to be Jewish. There’s a powerful sense of togetherness that comes from communal suffering

Another famous Jewish masochist was none other than Moses.

We all know the story. But after Moses and his followers cross the Red Sea and the pharaoh and his Egyptians drown chasing them (as if that wasn’t enough suffering), they spend 40 years wandering the desert, trying to reach the promised land. He ends up dying within sight of it, and you’ve got to wonder what killed him: dehydration or listening to 40 years’ worth of complaints from disgruntled Jews.

I’ve spent ages wondering why we as Jews must suffer for our faith. Though I never had to consider killing a family member for God or wander through a desert for decades, I did go through a religious trial of my own.

To become a woman in the Jewish tradition, you must have a Bat Mitzvah, (“bat” meaning daughter, the male version is “bar”, meaning son). When I turned 13, like many others in my age group, at my most spotty and socially awkward, with a mouth full of painful braces, I was to have my Bat Mitzvah.

I was going to have to sing a Torah portion in front of my extended family and peers. I spent months preparing, learning the Hebrew words with my tutor, Havah. I would spend two hours each week with her in her basement, which also housed her two stinky ferrets, painstakingly reading the Torah.

The sessions lasted for six months, and it was during this time that I started to question my religion. Why did I have to go through all this just to “become a woman”, which I was fairly sure was going to happen either way? It seemed that I was doing all this work just to follow a tradition I wasn’t sure I even wanted to be a part of.

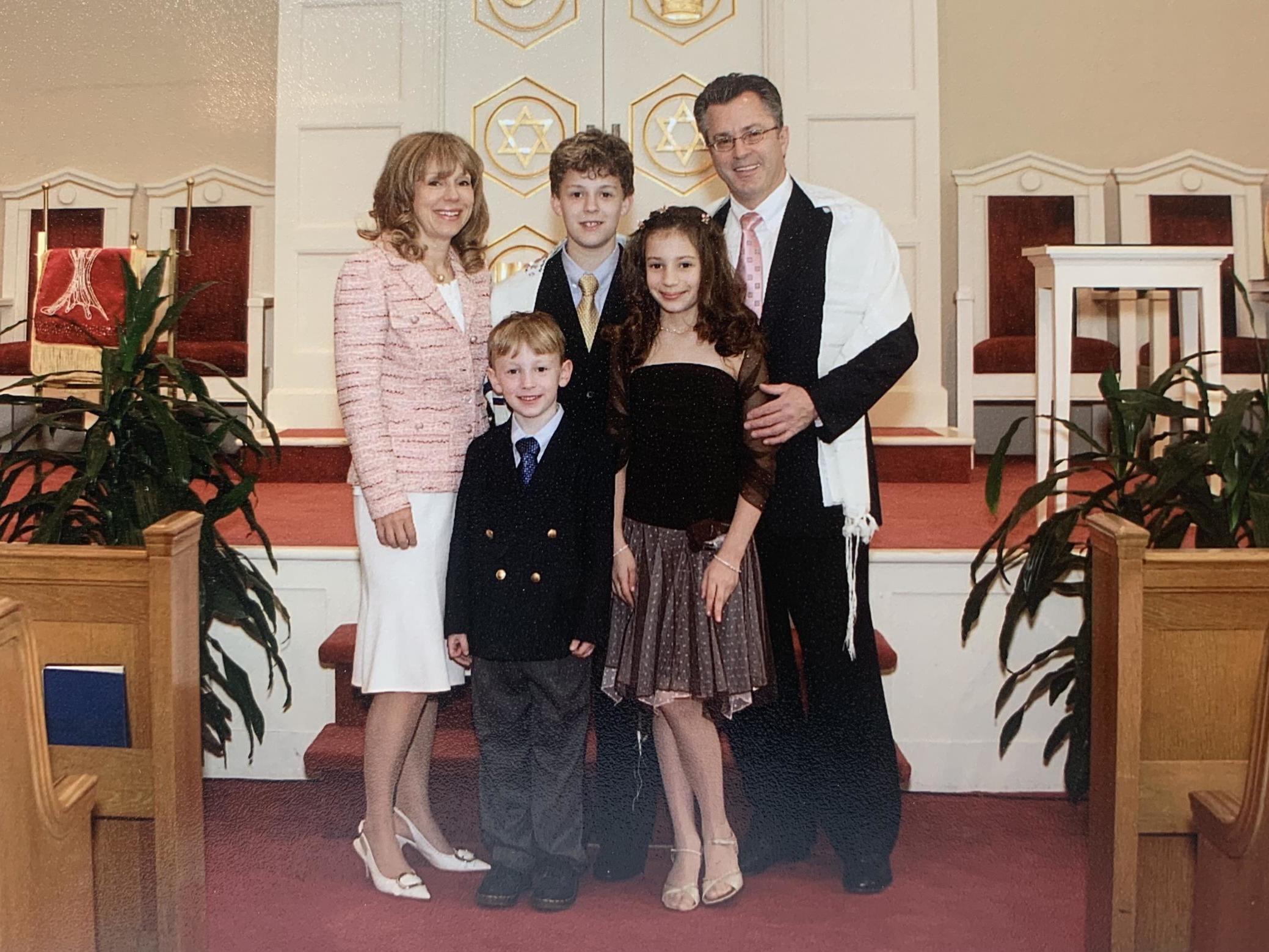

Yet on the day of my Bat Mitzvah, singing in Hebrew in front of all my family and friends, I had an unexpected feeling: pride. I was proud that I was able to read the words that had once been so foreign to me, and I had a sense of accomplishment that not many young people experience.

It was only through this extended period of suffering that I was able to learn something new about myself. It made me realise why people want to be Jewish. There’s a powerful sense of togetherness that comes from communal suffering. Suddenly, I had gone through the same test that all other Jews had, and now I was one of them.

It was through this experience that I was finally able to understand the point of Yom Kippur. The days spent without food, in deep contemplation, bring you closer not only to God, but to those around you. It’s through this togetherness that Jews have survived persecution through millennia.

So for all the kvetching I may do about Judaism, I’m glad I have other Jews that I can do it with.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments