The forgotten women who ended slavery in Britain

Forbidden to enter parliament, own property or vote, women’s political influence in the 1800s was severely curtailed. No wonder, then, that the names of abolition’s heroines have been all but wiped from memory, writes Mathis Clément

Last summer, the killing of George Floyd precipitated the biggest anti-racism protests in US history, with between 15 and 26 million people estimated to have taken part. The rest of the world quickly followed. By November, more than 4,000 towns and cities on every continent bar Antarctica had been thronged with demonstrators. The rallying cry proclaimed through loudspeakers and brandished on placards was simple: Black Lives Matter.

One of the most distinctive aspects of Black Lives Matter in contrast to earlier movements like Anti-Apartheid and Civil Rights is its lack of a charismatic figurehead. Instead, it is loosely structured as “a collective of liberators who believe in an inclusive and spacious movement”. An unfortunate effect of this philosophy is that the movement’s pioneers remain largely unrecognised – most readers will never have heard of its founders Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tometi and Alicia Garza.

The contrast between Cullors, Tometi and Garza’s pioneering importance and their public obscurity echoes the position of women who fought for the abolition of slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries. Ask any Briton what they know about abolition and you’re almost certain to hear the name William Wilberforce. And while it’s true that Wilberforce was crucial to the passage of the 1807 Slave Trade Act, it would have been impossible without the decades of pressure exerted by activists working outside parliament. Moreover the 1807 act only outlawed the trade in slaves – if you were already a slave in one of Britain’s Caribbean colonies, your status remained the same. Only after a further 26 years was slavery itself outlawed once and for all. Crucial were the efforts of women activists. Forbidden to enter parliament, to own property if married, and to vote, women’s political influence was severely curtailed. Nevertheless, they played an enormous role in abolitionist campaigns. Whereas Britain’s leading group was in favour of gradual abolition right up until 1831, women’s societies were united in arguing for an immediate end to slavery, employing disruptive tactics such as the 1820s sugar boycott. They faced opposition from male leaders, including Wilberforce himself, who instructed his colleagues not to speak at women’s events: “For ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions. These appear to me unsuited to the female character as delineated in scripture.”

Read More:

Elizabeth Heyrick was one of those most implacably set on immediate abolition. Born in Leicester in 1769, she was just 22 when the first sugar boycott spread throughout the country, in some places causing sales to drop by over a third. At this stage of her life, Elizabeth was not yet strongly engaged with politics. Only after the death of her husband of eight years and her subsequent conversion to Quakerism did she develop a fixation with the most pressing political and social injustices of the day. Surviving on an allowance from her father and the proceeds of a school she ran from her parents’ home, Elizabeth became a prolific author of political pamphlets. Her first was published in 1805 and condemned people’s tendency to rush into supporting wars. This was an especially unpopular opinion at the time – Britain was fighting Napoleon, whom propaganda portrayed as a bloodthirsty tyrant and an existential threat to the entire continent. But Elizabeth never allowed popular opposition to sway her from advocating what she believed was right. For instance, she vigorously opposed the widespread blood sport of bull-baiting (and is said to have rescued one bull on the eve of combat by buying it from its captors then hiding it in a nearby cottage until irate spectators had dispersed). In addition, she advocated for prison reform and supported striking weavers in Leicester, despite the fact that her brother was an employer in the industry.

However, in Elizabeth’s mind the worst of all social evils was slavery. Despite the passage of the 1807 Act, slavery itself still persisted throughout Britain’s colonies, and while a few campaigners were spurred on by this success to the next goal of full abolition, the movement as a whole lost momentum. The country’s biggest abolitionist group, the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, ceased its work. Foremost now in the public’s mind was the war against Napoleon for which taxes paid by Caribbean plantations provided crucial financial support.

Only in 1823, eight years after the Battle of Waterloo, did a nationwide successor to the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade emerge: the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the British Dominions. “Gradual” abolition was the mainstream view and was supported by Wilberforce himself. Far from being the idealistic radical of popular imagination, he was a conservative who believed that black people had “uninformed” minds and “extremely rude” notions of morality and that it was therefore “dangerous to the man himself and to all around him” to grant freedom straight away. The society’s timeline was for an end to slavery within 30 years.

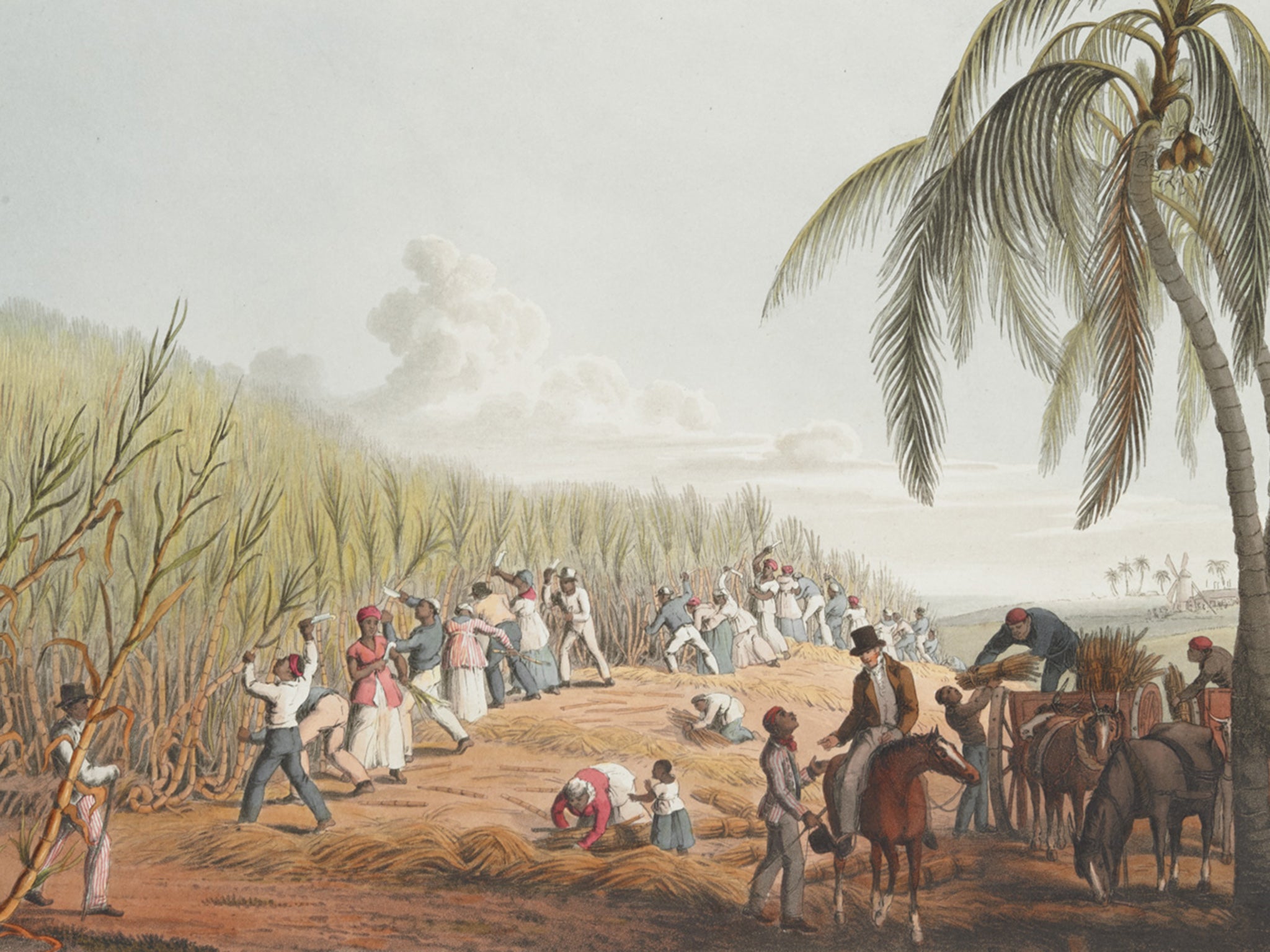

One reason it proved so difficult to pass the Abolition Act was the challenge of accurately conveying the cruelties of slavery, which had not been practiced in Britain itself since around 1800

Elizabeth’s best-known contribution to abolitionism came in opposition to this argument. In 1824 she published her pamphlet Immediate not Gradual Abolition, which very quickly became a bestseller, shifting hundreds of thousands of copies and in its first year alone going into three editions. The tone of her writing is uncompromising and fiercely moral – the idea of gradual abolition was “a very masterpiece of satanic policy”; even if eventually successful, “who can calculate the tears and groans, the anguish and despair … which may be added during the term of that protracted interval?” She called for people to take the issue into their own hands: “Why petition parliament at all, to do that for us, which … we can do more speedily and more effectually ourselves?” She would soon put this policy of direct action into effect.

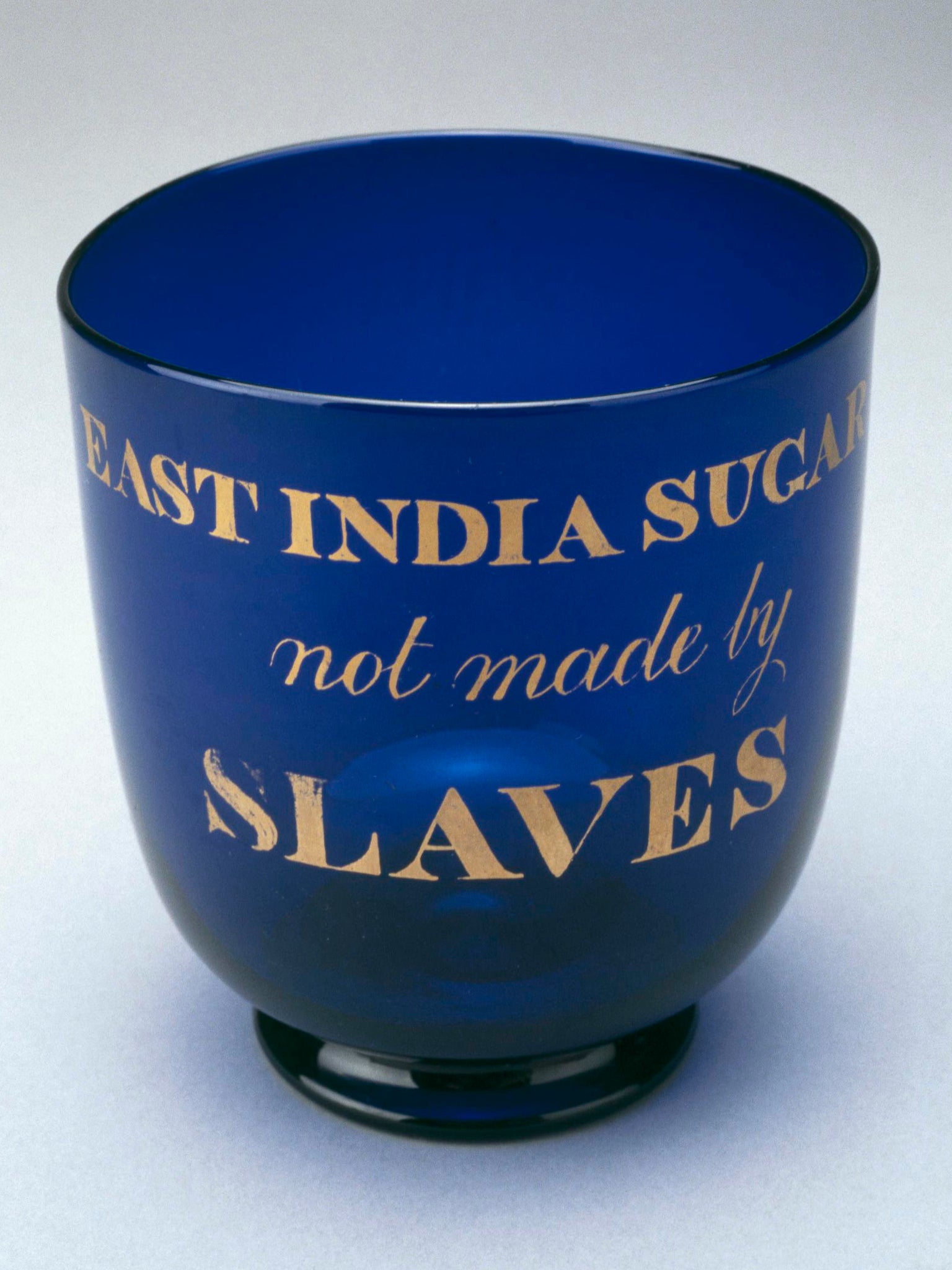

Within the year she had joined forces with four other women to establish the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves, which became a hub for women’s groups all over the country. Elizabeth drove the group to promote a second sugar boycott. As she put it, “Abstinence from one single item of luxury would annihilate the West Indian slavery!” Persuading local grocers’ shops not to stock sugar from the West Indies and encouraging total boycotts of businesses that did, Heyrick and her allies gradually tightened the screw on plantation owners. She also put pressure on the gradualists: in 1830, she persuaded the Birmingham Society to refuse its annual donation to the national society unless it dropped the word “gradual” from its title. Thanks to the financial clout of the Ladies Society, they agreed not only to drop the word, but also to support the women’s plan for a new campaign for immediate abolition.

Her goal now appeared imminent. But as the months rolled on, parliament made no moves towards enshrining total abolition in law and Elizabeth fell into a deep depression. She wrote to Lucy Townsend, a cofounder of the Birmingham Society, that “Nothing human can dispel that despairing torpor into which I have been plunging deeper and deeper for many months past.” On 18 October 1831, she died, two years before the Slavery Abolition Act passed into law.

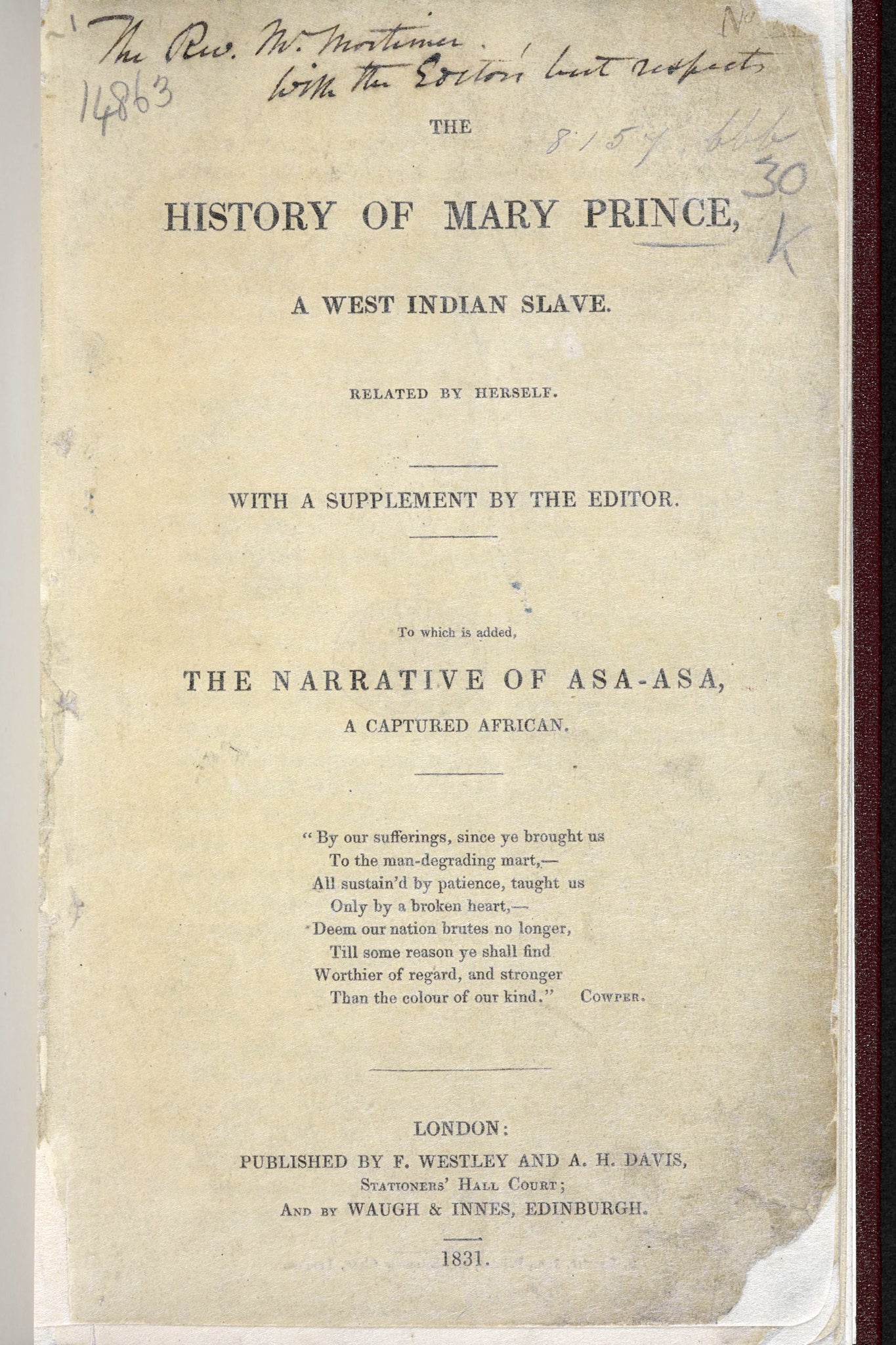

One reason it proved so difficult to pass the Abolition Act was the challenge of accurately conveying the cruelties of slavery, which had not been practiced in Britain itself since around 1800. Without streamlined foreign travel or modern media, the average Briton was cushioned from the real conditions that underlay so many of the products in their home. For this reason, the testimony of former slaves proved critical. One of the most important such testimonies is The History of Mary Prince. Published in 1831, it is the autobiography of a woman born into slavery in Bermuda who eventually escaped from her owners during a visit to London.

She arrived there in 1828, aged 40. Her master John Adams Wood had convinced her she would get treated for rheumatism, which she had developed during a decade’s hard labour in the salt evaporation fields on Grand Turk Island. This was a lie – in fact, the cold weather exacerbated her illness and Mrs Wood did not allow her any time to rest and recover. After one or two unbearable months, Mary decided she could not endure any more: she made the momentous decision to walk out on her owners. With only a little money and a few clothes, she made her way to the Moravian church, which found her lodgings with a shoe-cleaner and his wife. In November, she visited the Anti-Slavery Society, which tried in vain to persuade Wood to free her, writing him multiple letters and in 1829 presenting a petition to parliament arguing her case. It was rejected and shortly after, the Woods returned to Antigua. If Mary were to follow, she would be returned to slavery – she decided to remain in exile in Britain.

After a period of unemployment, she was hired as a domestic servant by Thomas Pringle, secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society. It was Pringle who encouraged Mary to go public with her story. Autobiographies by former slaves, including Quobna Ottobah Cugoano and Olaudah Equiano, had helped influence public opinion prior to the 1807 act, and Pringle was hoping that the publication of the very first slave narrative by a woman would cause enough of a stir to induce parliament to move towards total abolition. Since Mary was illiterate, Pringle hired his friend and fellow abolitionist Susanna Strickland to transcribe her story. Strickland spent weeks with Mary shaping her narrative. She acted not only as an amanuensis, but also as an editor, emphasising ideas she thought would be popular – such as Mary’s conversion to Christianity and her industrious attitude – and cutting passages that could endanger the project, above all those focusing on sexuality.

This decision was a taken in spite of the fact that part of what made women’s experience of slavery distinct from men’s was the extent of sexual violence they experienced. Public mores forbade the discussion of the subject in detail and both Pringle and Strickland knew that if they included the full range of her abuses, Mary would have been slandered as a harlot and her narrative thrown into doubt. Nevertheless, there are allusions to this particularly brutal aspect of slavery at several points in the book. She recounts that one of her masters, Robert Darrell “had an ugly fashion of stripping himself quite naked and ordering me then to wash him”. Strikingly Mary says that “this was worse to me than all the licks [of the whip]. Sometimes when he called me … I would not come, my eyes were so full of shame. He would then come to beat me.” She tells Darrell he is “a very indecent man” with “no shame for his servants, no shame for his own flesh”. The vehemence of her reaction, her willingness to be beaten rather than bathe him, and the way she openly brands him an “indecent man” imply more than just unwanted exposure – very likely these “bathing sessions” were opportunities for repeated rape.

We know Cécile sacrificed a pig, whose blood was consumed by the conspirators, binding them to a vow of secrecy. Yet other than that, very little else about her life is known

As well as deleting or eliding uncomfortable aspects of Mary’s story, Strickland emphasised ideas likely to win public support, especially Mary’s conversion and her self-reliant character. Her 1817 baptism and subsequent membership of the Moravian church are represented as turning points in her life, which set her on the path to redemption. Such tropes are typical of slave narratives. Though successful in terms of appealing to the reading public, Christianising slaves is morally dubious: its implication is that freedom has to be earned.

The book accedes to this idea too in its praise of hard-work – the Woods frequently left their property on business trips, giving Mary brief periods of time to herself, in which she sold provisions to ships’ captains, bought hogs at the docks to resell onshore, and ran a laundry service. She saved her earnings with the goal of accumulating sufficient funds to buy her freedom. This is depicted as a noble aim – she describes a former slave who achieved it, Daniel James, as “honest, hard-working, decent” and stresses that he continued working subsequently as a carpenter and a cooper. She later married Daniel and together they borrowed money to buy her freedom, but the Woods refused. The book does not highlight the irony of its emphasis on self-reliance with the fact that self-reliance proved useless as soon as it came into contact with her masters’ privileges. In fact, the conclusion doubles down on the earlier view, stating: “We [slaves] don’t mind hard work, if we had the proper treatment.” But, although this whole line of thinking seems repugnant today, when freedom from slavery is considered a basic human right and not a reward, at the time it was tactically effective: not only did it manufacture empathy among British Christians for faraway slaves, it also stressed their agency instead of just their victimhood.

Strickland’s influence proved astute. When The History of Mary Prince was published in 1831 it was an immediate bestseller, going into three editions that year alone. Pringle and the Anti-Slavery Society made sure to link Mary’s story to the wider abolitionist cause: every edition included a demand that parliament introduce a bill granting freedom to any slave who had been brought to Britain. The Birmingham Ladies Society put up money towards printings and encouraged members to read it. Mary even briefly worked for Lucy Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick’s confidante in her last days.

Despite the fact that she reads as a far less radical abolitionist than Heyrick, Mary’s apparent conservatism was a canny example of political realism, which manipulated the expectations of the reading public in order to advance abolition. Both her actions and words indicate a steely character, determined not to become a victim and uninterested in self-promotion. Once the 1833 act passed, Prince disappears from the history books. We do not know whether she remained in Britain or returned to live with Daniel in Antigua.

Focusing on figures like Heyrick and Prince risks presenting abolition solely as a process of peaceful campaigning and parliamentary law-making, confined to British soil. Ignoring the history of black resistance in the West Indies would obscure a major reason why the 1807 and 1833 acts passed when they did. Both laws were preceded by massive slave uprisings – in 1803 the Haitian Revolution ended in victory for the rebel slaves and the founding of an independent state, after more than a decade of intermittent conflict against several European powers; to this day it remains the only successful slave revolt in history. And in 1831, in Britain’s most profitable slave-colony, Jamaica, 60,000 slaves rose up against the planters, destroying over 40 sugar works and incinerating 100 houses. Adjusted for inflation, the damage amounts to over £100m today. The effects in Britain are expressed in a letter from Lord Howick, under-secretary for the colonies, to the governor of Jamaica: “It is quite clear that the present state of things cannot go on much longer, and that every hour that it does so is full of the most appalling danger … my own conviction is that emancipation alone will effectively avert the danger”. Without the material threat to colonial interests posed by rebellion and revolution, it is unlikely that any amount of activism at home would have achieved the abolition of so profitable an industry.

For over 100 years, this dynamic was for the most part ignored by historians of the period. CLR James’s The Black Jacobins, published in 1938, put the Haitian rebellion on the map as a crucial event not only in Caribbean history, but as part of the Napoleonic wars and the longer history of imperialism in North America. James’ insights have only recently started to filter into the mainstream – Sudhir Hazareesingh’s Black Spartacus about Toussaint Louverture, the leader of the Haitian rebels, was last year nominated for the Baillie Gifford Prize and Akala’s Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire, which has a chapter about the influence of Caribbean rebellions on abolitionism, was a 2018 Sunday Times bestseller.

But as with the memory of the abolitionist movement in Britain, the role of women in these revolts is still, to a large extent, buried. Toussaint and his successor Jean-Jacques Dessalines, remain the romanticised heroes of slave resistance. That they played leading roles is undeniable – however, their fame is also a result of the fact that there is far more documentation about both of their lives than for any other figure involved in the revolution. We know the names of many of the women involved, but little more. Take Cécile Fatiman, a vodou priestess who in August 1791 led a ceremony in Boïs Caiman which is commonly taken as the starting date of the revolution. In terms of Haitian national identity, the importance of this ceremony is equivalent to the adoption of the Declaration of Independence for the United States. We know Cécile sacrificed a pig, whose blood was consumed by the conspirators, binding them to a vow of secrecy. Yet other than that, very little else about her life is known – even her birth and death dates are unconfirmed. It is as if all we knew about Thomas Jefferson were confined to two months’ writing and redrafting in 1776.

There is more documentation – though still very little compared to Heyrick and Prince – about Suzanne “Sanité” Belair. Sanité was born an affranchi – a freedman, in around 1781. Many affranchis were of mixed race, which put them in an ambiguous position in Saint-Domingue’s (as Haiti was known by its French colonisers) strict racial hierarchy. The white population was divided into grands blancs (landowners, wealthy merchants and aristocrats), petits blancs (overseers and craftsmen) and blancs menants (workers and peasants). Below them were the affranchis and at the bottom, the slaves. Many affranchis identified with the French: they were educated in French and attended French entertainments – some served in the French military. They were also able to own land and slaves. But they lived under numerous restrictions: they were not allowed to vote or administer the colony; professions in law and medicine were forbidden and even wearing clothes in the style of colonists was not permitted. One of the main causes of the revolution was the affranchis’ ambition for legal equality with whites. When it became clear this would never be achieved peacefully, they joined the slaves plotting to revolt.

Sanité began armed resistance as a sergeant and over the course of the war earned herself a ferocious reputation – Jean-Jacques Dessalines described her as a ‘tigress’

Other than her status, we know nothing else about Sanité’s early life. In 1796, she married Charles Belair, Toussiant Louverture’s nephew and later his aide-de-camp. We do not know whether Sanité was a convinced rebel by this point, but in any case, Charles gave her access to the military leaders of the revolution, access that she used to become a fearsome soldier. By this point, the revolution had gone through several convulsive stages. The French had been beaten back; in response, the new revolutionary government, formed after the fall of the French monarchy in 1789, abolished slavery, hoping to keep control of the richest colony in the entire Caribbean; this prompted outrage from the United States and European colonial powers, who feared slave revolts in their own territories, so the British and Spanish attacked Haiti in 1793; Spanish forces were beaten back the next year, while the British were decimated by yellow fever; prime minister William Pitt (who would later sign the 1807 act) did not give up and in 1795 organised the biggest expedition in British military history at that point to conquer the entire French West Indies. The mission resulted in catastrophe, with over 50,000 dead and a cost of £4m (over half a billion today) to the Treasury. Had it succeeded, Britain would have controlled the two wealthiest Caribbean colonies – Haiti and Jamaica – making them the undisputed economic superpower: hard to imagine, under such circumstances, that the 1807 act would have been signed.

The defeat of the British marked three years of relative peace in Haiti. France was again in control, though reliant on Toussaint to maintain order. In 1801 however, he decided to break decisively away, proclaiming himself governor-for-life and calling for an independent Black state. Napoleon, now First Consul, sent a large force under his brother-in-law, Charles Leclerc, to reinstate French control. It is Sanité’s actions during this expedition that have earned her a place in history.

When the French landed in early 1802, the Haitian population was split in its support of Toussaint. Charles Belair, considered Toussaint’s heir-apparent, initially served Leclerc, but as the brutality of the French campaign increased and after Napoleon issued a decree reinstating slavery on the island, decided to switch sides. Sanité is often given credit for this change in allegiance, with multiple accounts attesting to her hatred for whites. The pair joined guerrilla rebels in the mountains of Verrettes, having rallied the population of L’Artibonite to their cause.

Sanité began armed resistance as a sergeant and over the course of the war earned herself a ferocious reputation – Jean-Jacques Dessalines described her as a “tigress” – which led to her promotion to lieutenant. Although women took part in the fighting from 1791, very few became officers. Sanité must have shown great leadership abilities to have overcome entrenched sexism and attain a commanding rank. Unfortunately, the actions that won her such prestige lie unrecorded and her next appearance in the history books is also her last.

There are conflicting accounts of her capture. In one, she was taken prisoner in a surprise French attack on Corail-Mirrault, after a portion of rebel troops had departed in search of ammunition and reinforcements. The soldier who captured her wrote that he “found her hidden behind a patch of high grass” and that once she had surrendered he went looking for Charles, who was “entrenched with some brigands, but seeing his wife prisoner he gave himself away”. Dessalines, who at this stage was in the service of the French, then wrote to Leclerc that he had proof Charles was “the leader of the latest insurrection” and that both he and his wife had to be punished.

CLR James presents a different account, in which Dessalines arranged a meeting between the couple and himself with the ambition of combining their forces, only to have them arrested and sent to Leclerc. By this point Toussaint was a prisoner in France and Dessalines, though temporarily in French service, had ambitions to turn on his masters and become Haiti’s sole leader. It is likely he saw Charles Belair as a threat for the crown.

Read More:

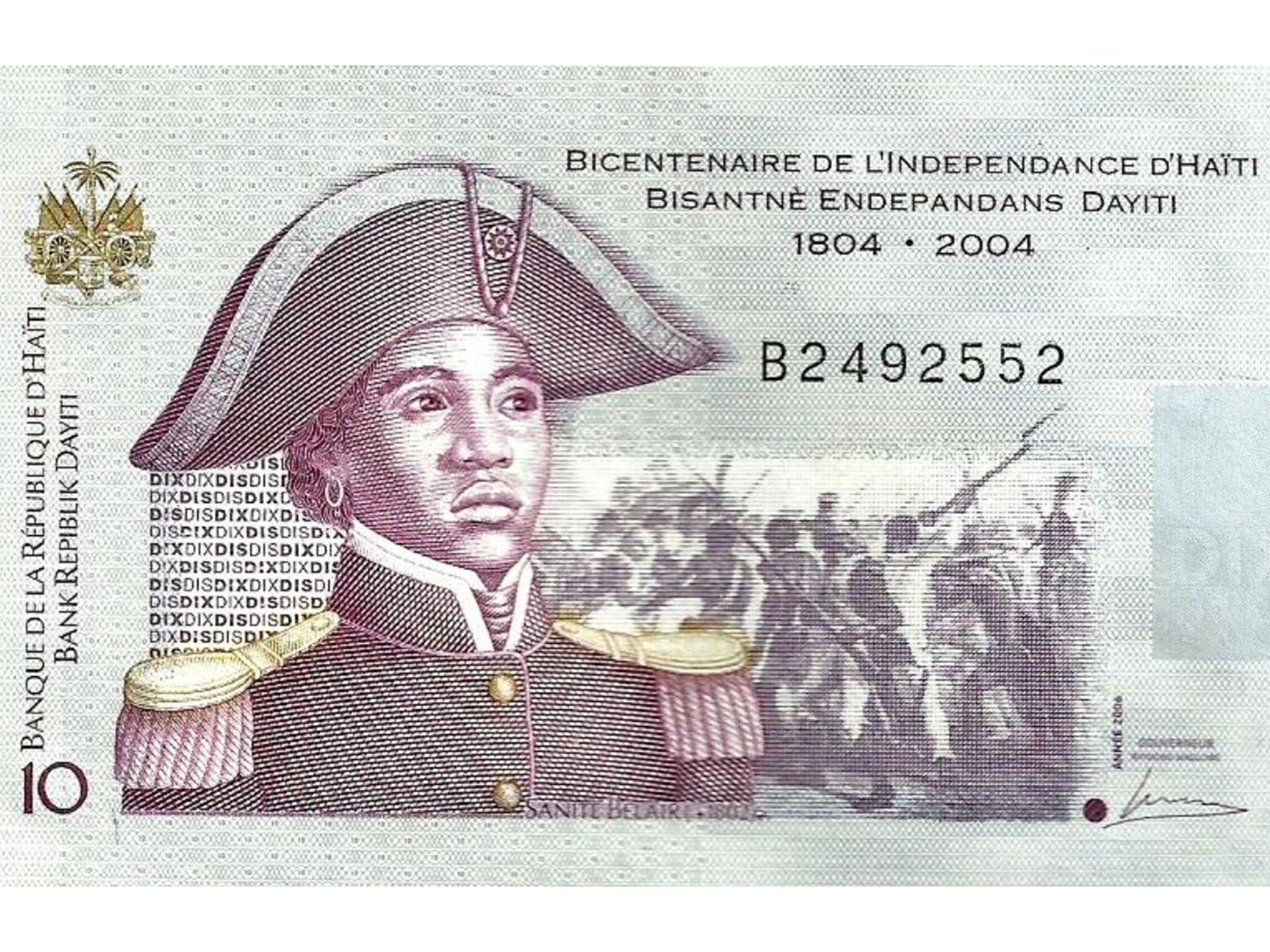

As traitors Charles and Sanité were to be executed, but the law differed for men and women – Charles would be killed by firing squad, whereas his wife would be decapitated. She refused. As a soldier, she argued it was her right to die like her husband. The executioner tried but could not force her to lay her neck on the block, so the commanding officer relented and agreed to her request. Charles went first, his wife exhorting him to die bravely. Sanité followed. She declined to wear a blindfold and is said to have died just after exclaiming “Viv Libète, anba esklavaj!” (“Long live liberty, down with slavery!”) She did not die in vain. Two years later, the freedom she craved was won and Dessalines selected as the governor-general of an independent Haiti. In 2004, she became the second woman ever to appear on a Haitian banknote: dressed in her military uniform, staring determinedly ahead, she makes a commanding figure.

The point of Women’s History Month is not to inflate or distort history, but to recognise that a great deal of received knowledge is distorted before it reaches us. It is an invitation to return to primary sources and unearth what has been hidden, played down and dismissed about women’s contributions to the past. The idea that abolition resulted from the heroic struggle of one man and the enlightened consciences of wealthy landowners in parliament is a convenient myth, which crumbles at the first contact with evidence. Were it not for the slave uprisings that threatened planters’ profits; the testimony of slaves like Mary Prince – cannily presented to appease the prejudices of the British public; and the radicalism of women’s societies, the 1807 and 1833 acts would never have come into force when they did. Toppling statues is a striking gesture, which should prompt deeper reflections on our past. This is an opportunity to engage in such reflections. I hope history teachers seize it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments