‘She was a proven winner’: Michèle Mouton and the history of women in motorsport

Michèle Mouton competed in World Rally Championships 40 years ago, yet she remains the last woman to have competed at the highest level of the sport – and the only one to win. Mick O’Hare tells her story

Forty years ago a woman signed to drive for Audi in the World Rally Championship (WRC). She would take part in 50 events and repay Audi’s faith by finishing runner-up in the competition in 1982. Yet despite sporadic privateer entries at the lower reaches of the WRC field, Michèle Mouton remains the last woman to have competed at the highest level of the sport, the only woman to have been signed by a leading team and the only woman ever to have won a world championship rally. Why? Well, why indeed?

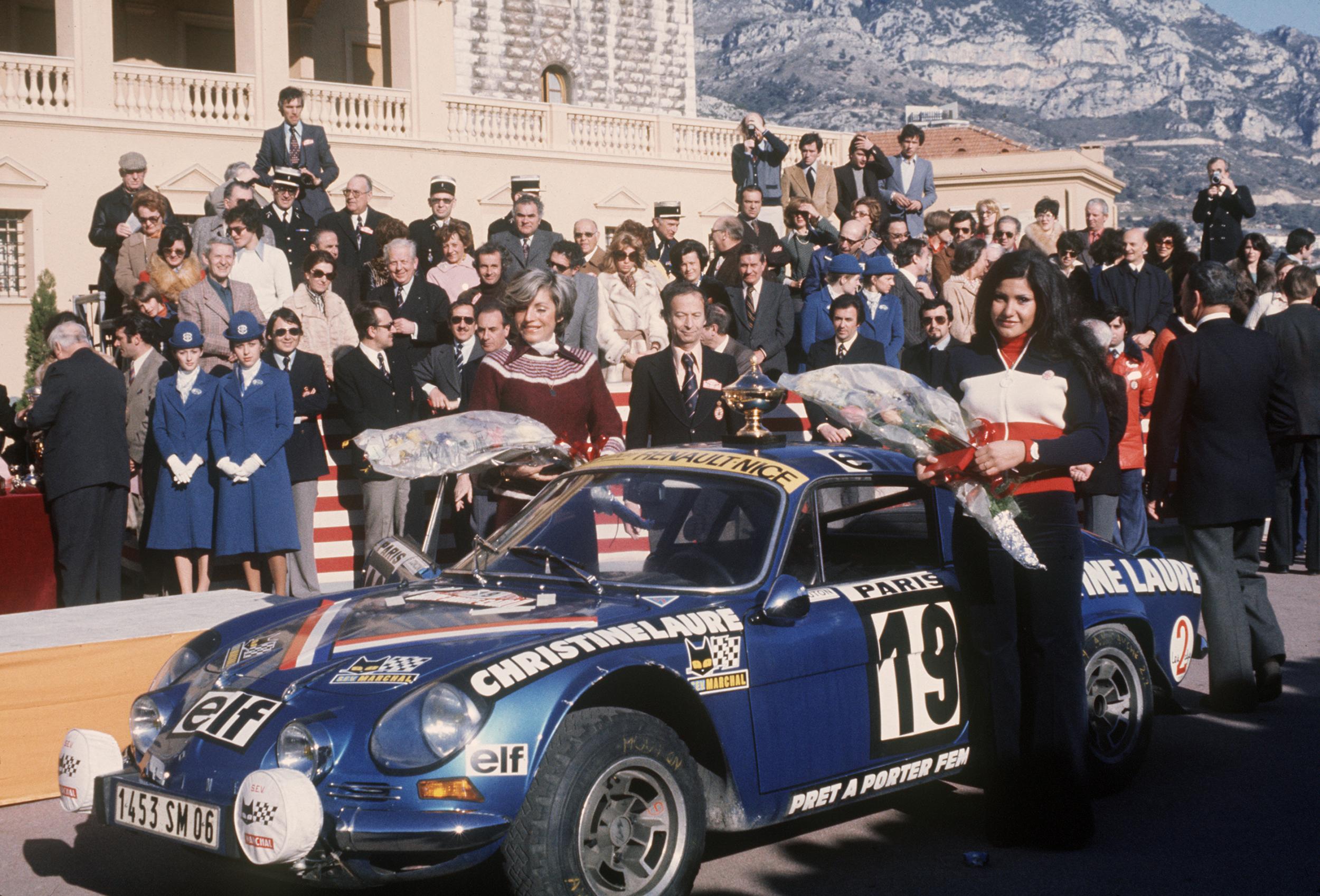

Based purely on officially sanctioned Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) world motorsport championships, Mouton is emphatically the greatest woman driver ever. In addition to four WRC wins, the Frenchwoman also raced in the annual 24 Hours of Le Mans and, as part of an all-female team, won her class in 1975. She was runner-up in the European Rally Championship in 1977 before Audi came calling. She then narrowly missed out on the 1982 world title to double champion German Walter Röhrl, losing by a mere 12 points but, along with teammate Hannu Mikkola, delivered Audi’s first world manufacturers’ crown.

Later in her career, she would win the notorious Pikes Peak International Hill Climb in the US and the 1986 German Rally Championship, the first woman to win a major rally title. At the time, it seemed she would be a trailblazer for females in motorsport, as the role and dynamic of women in general was changing rapidly. Feminism was driving emancipation and society was witnessing a wholesale transformation in attitudes to women in both the working environment and sport. Yet here we are in 2020 and, incredibly, Michèle Mouton remains an outlier, an exception.

Mouton, now 68, is currently the FIA’s World Rally Championship manager as well as its Women In Motorsport Commission president. She believes the lack of women in top-level motorsport is down to opportunity. “It’s obviously not ability,” she says. “It’s because women are so rarely offered the chance. Once I had the same equipment as the best men, it was down to me. I was, I suppose, lucky. Not because I wasn’t good enough, but because I was the woman who was given that chance. There are many women capable of doing what I did, but they aren’t considered.” Motorsport journalist Rachel Harris-Gardiner concurs: “At the time she wasn’t a total anomaly, the irony was there were other women emerging such as Carole Vergnaud, another French driver, who was winning minor rallies, or German Rena Blome. And they could have been competitive, but no major team picked them up, they have been somewhat edited out of history.” What might have been a golden era for women in rallying was missed.

Hence Mouton remains the only woman to have succeeded – or perhaps more pertinently – been given the chance to succeed at the highest level in rallying. And, unsurprisingly, it’s not just rallying. Motorsport in general has traditionally been unreceptive to female participation. Formula 1’s record is even more dismal. Only one woman, Lella Lombardi, has ever scored a world championship point (and a half point at that in the curtailed 1975 Spanish Grand Prix), let alone win a race. And Lombardi remains the last woman to start a Formula 1 race – in 1976. That’s 44 years ago.

Even today, motorsport remains at best an unconsciously hostile environment for women. As late as 2016 ex-Formula 1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone was saying women could not be taken seriously in Grand Prix racing. Women, traditionally and perhaps exasperatingly in these more enlightened times, have often been present on racetracks as a decorative adjunct. While only two women have actually sat in cars on a Formula 1 starting grid a rough guessitimate suggests that, over the 70 years of the Formula 1 World Championship, probably 10,000 women have stood on the same piece of tarmac acting as grid girls – models with placards marking the starting position of each car. Hundreds more act as the outward face of sponsors. Motorsport should be embarrassed, if not ashamed, of that statistic.

Formula 1 may have moved on by following the lead of its electric-racing counterpart Formula E in replacing grid girls with young fans, but on track, women are still marginalised. After comments like Ecclestone’s, it’s not hard to see why. Of course, it’s something Mouton had first-hand experience of as she made her way through rallying’s ranks. Early in her career, as she started beating her male rivals, she recalls that “there were all kinds of rumours. Maybe I had a different engine to help me win. After the Tour de Corse rally in 1975 my engine was taken by the scrutineers and stripped down to check it over. Obviously it was OK. After that their excuses had to stop.”

At the San Remo Rally in 1981 Ari Vatanen, the Finn who would win the world championship that year, announced: “Never can nor will I lose to a woman”. His assertion was badly timed. Mouton went on to win her first world championship rally that weekend, Vatanen struggled home seventh. Mouton’s Italian female co-driver Fabrizia Pons says: “Everybody, the men especially but also our team Audi to a certain extent, were surprised. Some didn’t like it at all.”

There was possibly an element of media value to Audi hiring her, but at the same time she was a proven winner. She wasn’t randomly selected as a woman driver

Mouton had an unconventional arrival into the sport. “I was planning to go into law,” she says, “but got friendly with a man who entered rallies.” He needed a co-driver – effectively the passenger navigator. “I didn’t even know what rallying was,” says Mouton, “although it sounded fun. But for some reason my dad, who also knew nothing about rallying, decided it was more dangerous to be a co-driver than the actual driver and said that if I insisted on entering he’d buy me a car to compete in.” She was successful beyond both their expectations.

When the call came from Audi in Germany after her European Championship performances it came as “a complete shock”, she recalls. “They spoke English which I didn’t speak so well and at first I didn’t understand that they wanted me to drive in the world championship. I just couldn’t believe it.”

She was petite and feminine and it’s oft been suggested that Audi thought she could add glamour to the team’s promotional efforts, alongside Finnish future champion driver Hannu Mikkola, who they expected would head up their push for the world title. Harris-Gardiner suggests that “there was possibly an element of media value to Audi hiring her, but at the same time, she was a proven winner. She wasn’t randomly selected as a woman driver. Audi had a good idea that she’d get the job done, but perhaps her being female made her stand out in terms of popular appeal.”

Whether the “glamour” story is true or sexist reinterpretation, her teammate treated her with respect. At one of their earlier press conferences, Mikkola told reporters that it wasn’t going to be easy with Mouton in his team. They laughed, he didn’t. He knew she was good. “Hannu helped me enormously, he taught me so much,” she remembers. So much in fact that in 1982 she was beating him and challenging for the world title. At the penultimate round on the Ivory Coast she was just a few points behind Röhrl but only minutes before the start news came through that her father had died. His last wish, however, was for her to race on.

At one point she had a huge lead but cruelly, after mechanical problems, she rolled her car on the final day of the rally. Röhrl won and became champion for the second time. Disappointingly, the German declared that he thought defeat to a woman would have devalued his performances. Mouton was still not receiving the credit she deserved from some quarters at least. But she was pragmatic: “It’s not so important, losing a sports title, compared to losing your father,” she said. “So I never dwelt on it.” She was, however, recognised with International Rally Driver of the Year at the annual Autosport Awards.

I would hate it when a photographer would come up to me and say, ‘Can you smile?’ I would say, go and find Mikkola or Röhrl and ask them to smile too

She was winding down her career by the time she won the famed Pikes Peak International Hill Climb in Colorado in 1985 (although she was still active enough to become German Rally Champion the following year), but her performance in the challenging and dangerous hill climb made her as famous in the US as elsewhere. Known as the “Race to the Clouds”, drivers attempt to set the fastest time over the 20-kilometre course’s 157 unguarded bends as it rises to the finish at 4,301 metres. Still, the carping continued as she broke the course record on her way to victory which appeared to inconvenience Bobby Unser of the famous American racing family who had set multiple records at the event. He was disagreeably verbose upon learning he had been beaten by a woman. Apparently Mouton smiled and offered to race him back down the mountain “if he had the balls”.

But having established such a legacy is there any sense of disappointment or even concern from her that instead of being a pioneer, ripping up gender stereotypes for others to follow, she remains the exception? “Yes,” she says. “But we are where we are. We can’t regret, we can only change the future.” Motorsport and feminism have often been uneasy bedfellows. Even years after Mouton’s retirement, when women have been successful, discord and contradiction have never been far away. In 2008 American Danica Patrick became the only woman to win an Indycar race (North America’s Formula 1 equivalent) and came third in the 2009 Indianapolis 500, the world’s richest motor race. She is arguably circuit racing’s most successful female.

Despite this, Patrick courted controversy by appearing as a cover model on men’s lifestyle magazine FHM, appearing in lingerie shoots and being voted “sexiest sportswoman” in a Victoria’s Secret poll. Susie Wolff, now a team principal in Formula E and the last woman to drive at a Formula 1 meeting (in practice only), has said she would be prepared to do similar if it advanced her career or brought in sponsorship.

Some campaigners believed that Patrick could have afforded a more positive role model for girls looking to succeed in sport – one where they shouldn’t have to trade on their looks. Others have argued that she was a pioneer for women in motor racing; what she did elsewhere was her own choice. Patrick herself said the money she earned allowed her to carry on racing and it was up to her how she earned it. It’s the kind of contradiction Mouton pointed out years ago when she said: “I would hate it when a photographer would come up to me and say: ‘Can you smile?’ I would say go and find Mikkola or Röhrl and ask them to smile too.” Mouton’s nickname “the devil with the face of an angel” was always a backhanded compliment (and one, again, that deemed it necessary to refer to her appearance).

It’s obviously not ability. It’s because women are so rarely offered the chance. Once I had the same equipment as the best men, it was down to me. I was, I suppose, lucky. Not because I wasn’t good enough, but because I was the woman who was given that chance

It’s ironic too that motor racing is one of the few sports where both sexes should be able to compete equally. Last year saw a new single-seater, circuit-racing competition for women drivers only – the W Series (this year’s is currently suspended during the coronavirus crisis). Again controversy was close at hand. Some questioned whether a single-sex competition would eliminate the apparent prejudice whereby impressive female drivers are often overlooked in favour of mediocre males. Its CEO Catherine Bond Muir argued at its launch that “there are simply too few women racing. The W Series unleashes their potential.” “Surely it’s better than not racing at all,” said Alfa Romeo’s Formula 1 test driver Tatiana Calderon. And the W Series’s first champion, Briton Jamie Chadwick, argues: “On balance, right now I think it’s necessary. Women aren’t being given chances elsewhere.”

Others are less sure, seeing W Series as potentially patronising and pointing the finger of blame for women’s lack of progress instead at sexist attitudes found in motorsport generally. German Formula 3 driver Sophia Flörsch (who competes against men), said: “I agree with the arguments, but I totally disagree with the solution.” Harris-Gardiner is not overwhelmed by W Series either. “I think it may do some good in terms of role modelling for young girls, but I’m not convinced that keeping female drivers in a controlled W Series bubble instead of letting them form relationships with other good teams will help their careers long-term.”

Mouton’s opinion is equivocal and necessarily diplomatic. “W Series is a good platform,” she says. “And it gets women racing. But anybody who wants to succeed must show they are the best, not just the best woman. At some point, they will have to beat the men too.”

So if Mouton, chair of the Women in Motorsport Commission, has reservations, what solutions does she propose? How will more women be attracted to and succeed in motorsport considering it seems to have inbuilt male hegemony? If not W Series, then what? “It’s a matter of providing opportunities,” she says. “There’s simple mathematics at work. Right now few girls go into motorsport because they look at the top echelons and it’s all men, which means it stays that way. So we need to convince people motorsport is inclusive. Quite often the issue is cost. Add in the lack of equal opportunities and women suffer disproportionately. We must focus on the grassroots, educate girls about motorsport and make sure more try it out at an affordable level.” Mouton believes by doing this, girls will be competing at the cheaper, lower levels directly against boys and, when they start to win, will consequently get the same opportunities.

If you level the playing field at the start, where it’s affordable to do so and money and sponsorship are less of an issue, then the best girls will be picked up by the driver programmes of professional teams, alongside the best boys. Mouton and Women in Motorsport backed this approach with the Girls on Track karting challenge. “We have already worked with more than 1000 girls giving them a chance to race in a kart. And it’s not just drivers, we want team managers, mechanics, designers,” she adds.

Harris-Gardiner agrees with Mouton that “we need to play the long game. Girls on Track is part of that.” And she too sees it coming down to the maths. “The percentage of successful male drivers in comparison to the total number of racing drivers is tiny. The number of female racing drivers is much, much smaller so if the percentage of really good ones is the same, we can only expect a minuscule number to succeed. We need to get more girls and young women involved early and working with the best teams and engineers, and in the best cars. That’s a big project, especially keeping girls involved during their teen years when many drop out of sports.” As an alternative to female-only racing series, Harris-Gardiner would prefer to see more initiatives like the forthcoming Extreme E series which will see electric off-road racing in places such as Greenland and Nepal. “It’s environment-led,” she says, “with projects to help and bring awareness to areas already damaged by climate change. Crucially each car will have a male and a female driver, each sharing equally the driving and co-driving roles. So it means women are guaranteed spots in the major teams.”

Doubtless the success or otherwise of Mouton’s presidency of the commission will become clear in the coming years, but her personal legacy as a driver will remain intact whatever the outcome. “I wasn’t actually motivated by a desire to beat men,” she says. “I just wanted to prove I could be at their level.” She certainly was. Rallying historian Graham Robson has described her as “the driver by whom all other females measure their skills and achievements”. Back in 1981 Motor Sport magazine wrote that she “is never shown quarter by her male rivals, nor does she ask any, for she is a rally driver among rally drivers, and her skill puts her up among the world’s best”. Mouton, a member of the Rally Hall of Fame and a recipient of France’s Légion d’honneur, effectively moved the goalposts for women in motorsport, it’s just a pity that those goalposts often appeared to be hidden behind a brick wall of implacable preconception.

And at this point it’s maybe worth reminding ourselves of a slogan from the W Series: “Talent does not have a gender.” Michèle Mouton proved that four decades ago. Unfortunately, we are still waiting for her successor.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments