Long before the Ouija board the Victorians loved a seance

William Rossetti’s seance diary records in meticulous detail every moment from 20 sessions, and every famous participant is also noted down, reports Barrie Bullen

Death and disease are no strangers to the streets of Britain. By the late 19th century, tens of thousands of people had contracted fatal infections, such as cholera, smallpox and scarlatina, beginning with the first cholera epidemic of 1832, when detailed records first started being kept.

Wave after wave of typhoid also swept over the population where cause, diagnosis and cure were all equally uncertain – and social class provided no protection. In his novel Bleak House, Charles Dickens recorded fever deaths in the slums of London. But the most prominent flesh-and-bone victim was Queen Victoria’s own husband, Prince Albert. He was diagnosed with typhoid and died in December 1861.

Meanwhile, a bizarre form of comfort was at hand. In 1848 in Rochester, New York, two sisters claimed to have received messages from the spirit of a long-dead inhabitant of their house, and their conversation with him fired the imagination of America. “Table-rapping” swept across the American continent and modern spiritualism was born; and in the early 1850s it crossed the Atlantic. Seances began to take place in the parlours and dining rooms of France, Germany, Italy and Britain. All communication with the spirits was done through letters of the alphabet, similar to ouija boards.

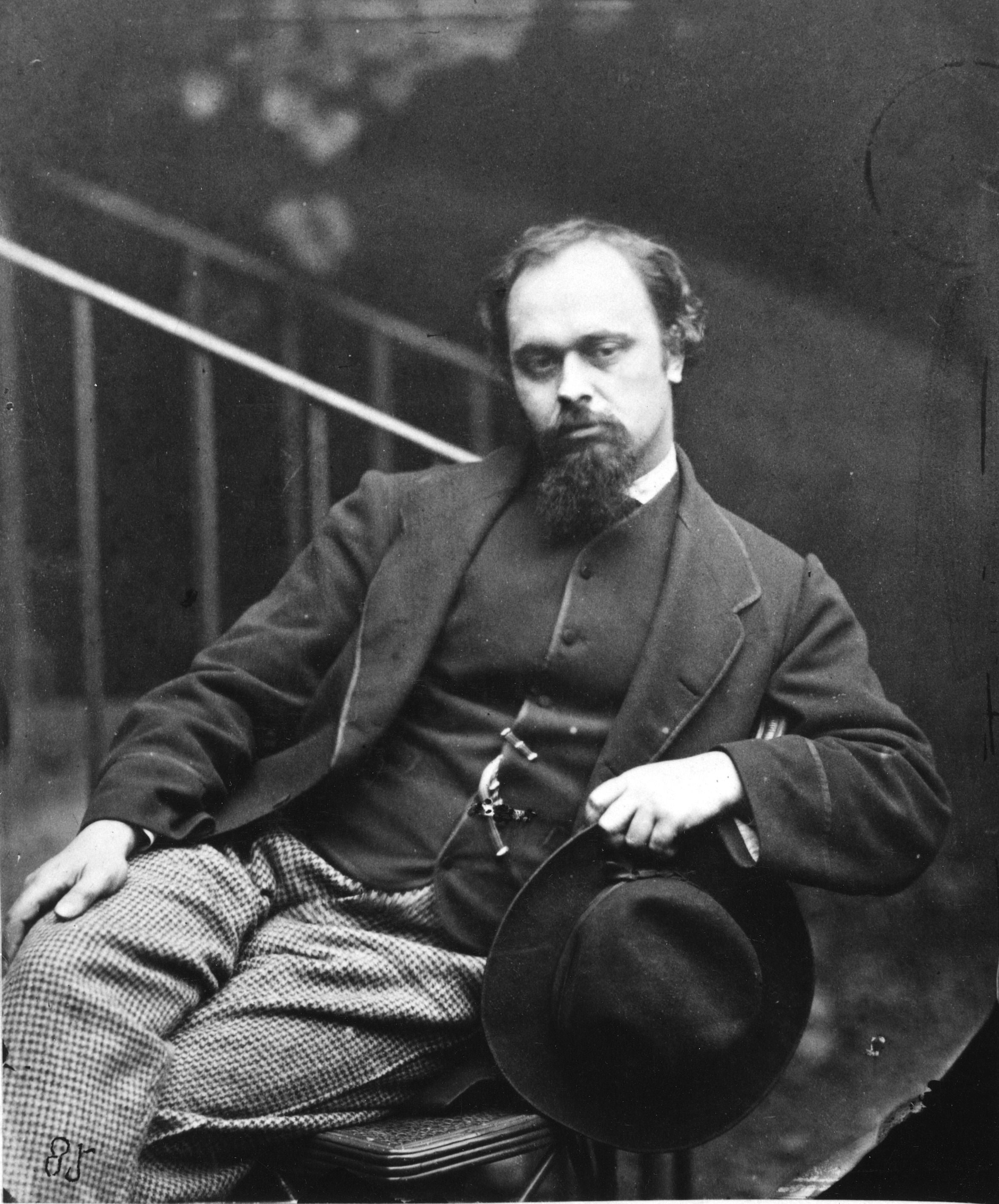

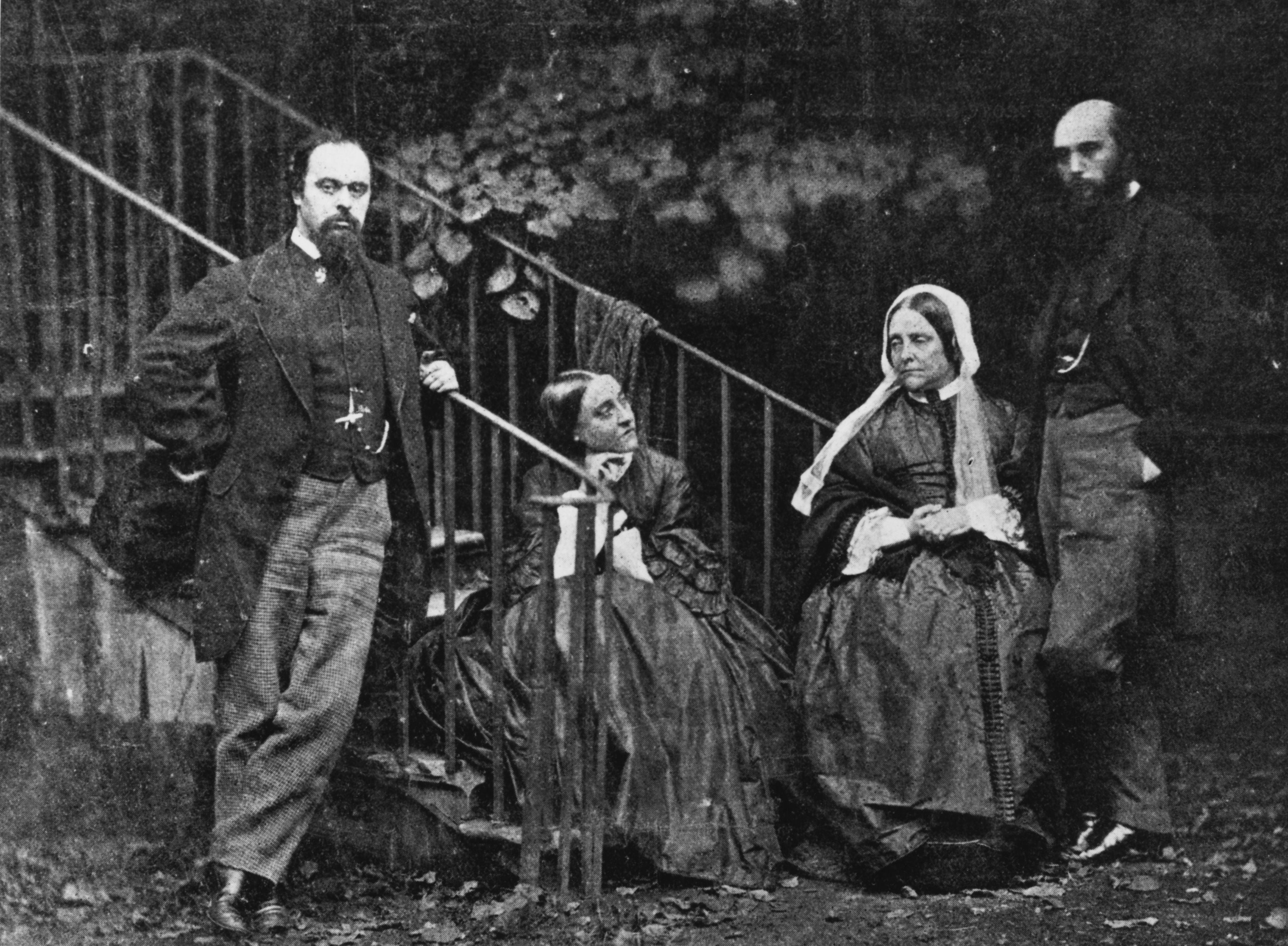

The fashion for spiritualist seances was fuelled by those who longed for communication with long-lost loved ones or friends. The pre-Raphaelite poet, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, for example, started holding spiritualist seances after the death of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal, in 1862. Many of these took place at his home in Chelsea, attended by friends and acquaintances. The most regular participant was his brother, William Michael Rossetti.

Pursuing William’s stray memories led me and my colleagues, Rosalind White and Lenore Beaky, to the special collection of the library of the University of British Columbia where a small notebook by William (labelled “Seance Diary”) is kept. We have co-edited this meticulous record of 20 seances that William attended between 1865 and 1868, published for the first time this year as a volume titled Pre-Raphaelites in the Spirit World – The Seance Diary of William Michael Rossetti.

Many of the seances feature conversations he and his brother had with Elizabeth Siddal, whose presence punctuates the three recorded years. Many others feature dead friends and relatives. According to William, on one occasion their uncle, Gaetano Polidori, once Lord Byron’s doctor, correctly confessed that he had died by suicide. On another, their Italian father, Gabriele Rossetti, was reportedly summoned and addressed the brothers in his native Italian.

Many of the spirits that William said rose from the dark were artists, often responding accurately to being asked about when, where and how their deaths had occurred. Some of the most remarkable manifestations involve figures of whom there is no evidence yet whose accounts have been confirmed recently through the archival research of the editors of this volume. And so, like many people curious about spiritualism, we remain mystified by the bizarre accuracy of some of the messages coming from the spirit world through these diaries.

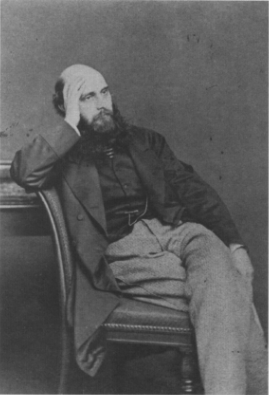

William Rossetti was a diligent civil servant with a strong sense of probity and an eye for detail, and what he gave us in this little notebook was an unparalleled insight into the Victorian spirit world.

Victorian seances

The Rossettis were by no means the only Victorians committed to a belief in the occult. The poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, the social reformer Robert Owen, the evolutionary biologist Alfred Russel Wallace and the novelist Arthur Conan Doyle were just a few more passionate believers in the power of seances. William Ewart Gladstone, Alfred Tennyson, John Ruskin and the painter GF Watts were all members of the Society for Psychical Research, a badge of belief in spirit activity, and it was even rumoured that Queen Victoria received messages from Prince Albert via a psychic teenage boy named Robert James Lees.

He claimed not only communication with angels and demons, but spoke of how he had been admitted into the spirit world and how he had returned to the terrestrial sphere to tell the story

Mediums became celebrities. The most famous, DD Home, came to Britain from America in 1855. In 1853 the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray met him in America and, convinced of his authenticity, used the pages of his journal, The Cornhill Magazine, to promote Home’s career. In Britain, one of the most famous mediums was Mary Marshall, who had risen to prominence in the late 1850s and who presided over a number of seances recorded by William Rossetti.

But dealing with the dead created as many sceptics as it did fans. The novelist George Eliot and her partner GH Lewis turned to the press to denounce spiritualism as a sham. Meanwhile the journal, Once A Week, described the aforementioned Mary Marshall as “poor”, “vulgar” but hugely eminent as the “washerwoman medium”, describing “the abominable profanity and wickedness” of her seances.

The satirical journal, Punch, was quick to seize on the comic potential of the new vogue. Weekly cartoons depicting humorous dialogues with the dead appeared. Like this piece of doggerel in which Mr Punch:

Wanted to know what on earth are the merits

That make Mrs Marshall affected by ‘sperrits!

Wanted to know why respectable dead

Come back to life at five shillings a head.

The most consistent war on spiritualism, however, was waged by the powerful voice of Dickens. He was outraged by DD Home. In 1860, he denounced Home’s autobiography as odious, written by a ruffian and a scoundrel and agreed with George Eliot that Home was “an object of moral disgust”. As for Mary Marshall and her daughter, he said they possessed the “duplicity and legerdemain of… two illiterate conjurors” playing on “the holiest and deepest feelings of their audience”.

While the debate about authenticity raged, seances – in public and in private – took place throughout the country. Some were spectacular displays of showmanship involving large audiences; some were intimate, devout gatherings, while others took the form of after-dinner entertainment.

The social, anthropological and religious role of spiritualism in Victorian culture has been much debated, but one important factor drove people to the darkened room of the medium: the need to contact a dead loved one. It was this motive that lay behind Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s desire to communicate with her brothers, both of whom died in 1840: in February Samuel died of a fever in Jamaica and shortly afterwards her favourite brother, Edward, was drowned in a sailing accident in Torquay in July.

Biologist Alfred Russel Wallace started a career of his own in spiritualism after the death of his brother in 1845. And the death of Conan Doyle’s son, Kingsley, strengthened the crime writer’s lifelong belief in the occult. Death also lay behind the seances in William Rossetti’s diary, since many of them were driven by his brother’s desire to reach out to the spirit of his dead wife.

Though there are many records of spiritualist experiences in the 19th century, what makes William’s diary so valuable is its detail. Every moment in the 20 seances is meticulously recorded, every participant and his or her reaction to the events is noted down, and the presence of so many prominent artists from the Pre-Raphaelite movement casts each of their personal beliefs and prejudices in a new light.

The spirit world

The lights are dimmed. The candles flicker. William asks some questions of the spirit of Elizabeth Siddal, Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s wife. His questions involve a picture that he has just sent to a wealthy patron in Birkenhead called George Rae. The questions are strange, the responses reported by the diary monosyllabic but accurate.

William: Did you consider that picture which Gabriel sent away the other day one of his very best?

Elizabeth: Yes.

William: Do you know to whom it has gone?

Elizabeth: Yes.

William: Give initial of surname?

Elizabeth: R [correct for Rae]

William: Do you know in what room of Rae’s house that picture is now placed?

Elizabeth: Yes.

William: Dining room?

Elizabeth: No.

William: Drawing room?

Elizabeth: Yes.

William: How many in the whole house?

At this point, a pause of some 15 minutes ensues, within which no answers are reported.

William: During that pause were you absent looking into Rae’s house?

Elizabeth: Yes.

William: Can you give me any idea of the process by which you pass from one place to another?

Elizabeth: No.

Dante’s fascination with the occult went back to his early experiences of the poetry of Dante Alighieri in the scholarly work of his father Gabriele. In the course of his work, Gabriele frequently invoked the authority of the Swedish mystic, Emmanuel Swedenborg who, around 1744, began to have visionary experiences of the afterlife. He had become a seer, he said, by God’s command to explain the correspondences between life on earth and life in heaven.

He claimed not only communication with angels and demons, but spoke of how he had been admitted into the spirit world and how he had returned to the terrestrial sphere to tell the story. Consequently, Dante Rossetti’s poems and pictures are filled with spiritual experiences; with stories of hauntings and uncanny events. In the late 1850s he began to participate in seances, but it was the death of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal, that lent his participation a new urgency.

Prior to her death, Siddal had been suffering from postnatal depression caused by a stillbirth. Driven to despair by Dante’s long-term infidelity and neglect of her, she took an overdose of laudanum. Dante was consumed by guilt and filled with remorse and, as some kind of compensation, he buried the whole manuscript of his unpublished poems in her coffin. But no sooner had she been placed in the earth than he began to have nightly visions of her in his bedroom. At that point he decided to try and look for her in the afterlife.

In October 1862, abandoning the house which they had shared, he took up residence beside the River Thames, where he began holding seances with his new friend, the American painter James McNeill Whistler. Many years later, Whistler spoke of the “strange things that happened when he went to seances at Rossetti’s” since, according to William’s daughter, Dante was “anxious to get some message” from Elizabeth.

William Rossetti’s seance diary

By the time William began his seance diary in 1865, he was already a firm believer in spiritualist communications. Some of the seances he recorded came under the auspices of amateur mediums.

The richest and most dynamic ones took place under the mediumship of two professionals, Mary Marshall and Elizabeth Guppy, and the very first one he recorded took place in Marshall’s house. William was accompanied by his artist friend, William Bell Scott. The two men, who were certain that the Marshalls had no personal knowledge of them, wanted to make contact with the recently deceased brother of Scott’s mistress, Spencer Boyd.

The spirit was asked about the Rossettis’ father Gabriele in the afterlife, about the nature of Christ, and about the nature of the manifestations that they had recently witnessed at another seance

The information that emerged from this seance was striking. The spirit of Spencer Boyd was reportedly summoned and stated, correctly, that he had died in Scott’s home, providing the address together with the date on which he had passed away. He is also reported as correctly telling the group that he had heard of, but never met, Scott in person.

More startlingly, however, was a communication with people of whom there is no evidence that anyone present had any knowledge – yet whose accounts have been subsequently confirmed by our own archival research. In February 1866, for example, a New Zealand Maori chief calling himself “Hemi” is reported to have appeared out of the dark. Sources show that he claimed to have met William three years previously in Newcastle, when the chief was touring Britain exhibiting Maori dances.

Information gathered from historians in New Zealand, and our own research in the archives of local newspaper the Newcastle Chronicle, confirmed that in the week beginning 14 September 1863, a group of “Maori chiefs” had indeed performed to audiences in Newcastle. On that same day, Dante wrote a letter to a friend saying, in passing, that his brother was about to leave on a visit to Newcastle.

On other occasions, what were called “aports” were allegedly materialised. Eau de Cologne and water were described showering out of nowhere, books thrown from the bookcases and, in one incident, the medium asked the participants if they would like to receive flowers. In response, roses, ferns and jonquils were requested and, to their amazement, appear to have dropped out of the darkness on to the table in front of them or on to their laps. Dante invited Jane Morris, the wife of William Morris, to two of these seances, where she claimed to have seen unexpected lights and felt cold draughts of air pass over her hands.

The most moving and dramatic seances, however, are those that featured the spirit of Elizabeth Siddal. In the second seance recorded by William, his brother spoke to her with clear reference to the past. “You used to give me clear [and] significant answers,” he said, “but of late the reverse: can you tell me why?” He writes that she had no answer. In a later seance, the spirit reportedly confessed that she knew William Bell Scott, and thought that William had been a very affectionate brother to Dante. Later, at the home of Thomas Keightley, historian and folklorist, the diary describes her telling the participants that she knew William Morris, and correctly told them his London address.

The most intensive cross-questioning of Elizabeth’s spirit took place in the very last seance at 2am on Friday 14 August 1868. In this, the spirit was asked about the Rossettis’ father Gabriele in the afterlife, about the nature of Christ, and about the nature of the manifestations that they had recently witnessed at another seance. The most touching exchange is described as occurring between Dante and Elizabeth.

Dante: Are you my wife?

Elizabeth: Yes

Dante: Are you now happy?

Elizabeth: Yes

Dante: Happier than on earth?

Elizabeth: Yes

Dante: If I were now to join you, should I be happy?

Elizabeth: Yes

Dante: Should I see you at once?

Elizabeth: No

Dante: Quite soon?

Elizabeth: No

“Bogie pictures”

Though they are not usually linked, during this period, both Dante and Whistler created pictures with an occult significance. Dante’s drawing How They Met Themselves (1860-64) is a ghostly double in a dense wood. It was completed in its first version during his honeymoon in 1860, and reworked as a coloured version in 1864. Dante called it his “bogie picture”.

William said of it: “To meet one’s wraith is ominous of death, and to figure Elizabeth as meeting her wraith might well have struck her bridegroom as uncanny in a high degree. In less than two years the weird was woefully fulfilled.” Then, in 1863, both Whistler and Dante embarked on paintings with links to other spiritualist experiences.

Whistler’s Symphony in White No 2: The Little White Girl (1864) has a contemporary setting and, like Dante’s drawing How They Met Themselves, it is also a doppelganger work: in it, Jo Hiffernan, Whistler’s mistress, and her reflected image gaze down towards a lacquered Japanese box that Whistler employed in seances. Attached to the frame are Swinburne’s lines:

Art thou the ghost, my sister,

White sister there,

Am I the ghost, who knows?

Dante Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix (1864-79) was begun at about the same time. Its original title was “Beatrice in a Death Trance”, a Dantean image that linked the death of Beatrice Portinari, the woman believed to be the muse for Dante Alighieri’s Vita Nuova, beside the Arno with Elizabeth Siddal’s death beside the Thames. The painting was based on an unfinished portrait of Elizabeth and depicts the moment of her passage from life into death. The picture came to the notice of the prominent spiritualists William and Georgina Cowper-Temple.

William Cowper-Temple was president of the Board of Trade, and he and Georgina presided over seances in their family home with the most famous mediums of the day. In September 1865 they began to take an interest in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s work. They frequently visited his studio where he was working on the painting and offered to buy it as a genuine spiritualist work. It was beneath this picture and in the same studio that Dante was trying to conjure up the spirit of Elizabeth Siddal.

The Rossetti brothers have long been known for their contribution to writing and painting in the 19th century, but the record of their seances connects them to the widespread Victorian preoccupation with the occult.

The huge mortality rate in Victorian Britain encouraged large numbers to seek the support of mediums. Similarly, around 1918 the carnage of the first world war and the waves of influenza created a new interest in spiritualism. Perhaps in this context, it’s unsurprising that the Covid-19 pandemic is reportedly driving a revival of the ouija board.

Though spiritualism is still surrounded with an air of suspicion and mystery, William Rossetti’s diary shows that believing one has made contact with the next world is usually a source of consolation and reassurance. For some, spiritualism was as precious as fiction: a place to go to when needing to step away from too harsh a reality.

Barrie Bullen is a visiting professor at Kellogg College, University of Oxford. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments