The changing nature of offence and why it causes pain

People today aren’t any more sensitive than previous generations. They just takes offence at different things. Andrew Gold on why words hurt us

The team is like musical chairs. Someone gets in for a game, does well but then has a Holocaust.” These are the words Bristol Rovers manager Joey Barton used to describe his team’s poor performance earlier this season. He was being interviewed after losing 3-1 to Newport and, while searching for a word strong enough to convey just how bad his club had played, found on the tip of his tongue a reference to the Shoah.

Despite the furore caused by Barton’s comments, pundit and ex-footballer Carlton Cole did the same thing just a month later. Discussing West Ham’s upcoming games, he said: “You’ve got to give Man City some respect […]. Otherwise it will be a Holocaust and you don’t want that.”

Both former players activated the modern “sorry if I offended anybody” get-out clause, suggesting that either they couldn’t quite remember what they said, or that the feelings of the Jewish people – six million of whom were murdered in said Holocaust – could only be considered in the conditional. The Jewish community might reply in kind with: would that “if” were “that”.

The Holocaust Educational Trust certainly thinks it was offensive: “A bad football match is nothing like the Holocaust and this is clearly inappropriate.” And Bristol councillor Fabian Breckels referred to the comments as “appalling” and went so far as to suggest Barton ought to be “considering his future”.

Should Jews like myself feel aggrieved? Should those who say offensive things have to resign from their jobs? In judging offence, we have to contextualise it within the society of the time. Despite appearances, it’s not that today’s world is necessarily more sensitive than its previous iterations. It’s just that the musical chairs of sacred language shimmy around as much as the make-up of Barton’s football team.

With cancel culture and censorship at the heart of much of today’s culture war debates, there is a clamour from some of the free speech advocates among us to revisit the past, and its maxim of “sticks and stones”. But “words will never hurt us”? Let’s be honest, that has never been the case. In fact, a verbal jab to the gut can be excruciating. Chaucer, Shakespeare and Austen knew this timeless and universal truth.

“I wish I had your balls in my hand… I’d cut them off,” wrote Chaucer in The Canterbury Tales. “Thine face is not worth sunburning,” composed Shakespeare in Henry V. And as I never tire of reminding my step-mum, Brigit, Jane Austen wrote in Love and Friendship: “She was very plain and her name was Bridget. Nothing therefore could be expected from her.”

Words can even end friendships. When magician Houdini described spiritual mediums as “human leeches”, it led to his falling out with Sherlock Holmes writer Arthur Conan Doyle. The latter’s wife, Jean, believed she could communicate with the dead. George Orwell was described by literary critic Cyril Connolly as someone who “could not blow his nose without moralising on the conditions in the handkerchief industry”. And Ernest Hemingway wrote of his own literary rival: “Poor [William] Faulkner. He thinks big emotions come from big words.”

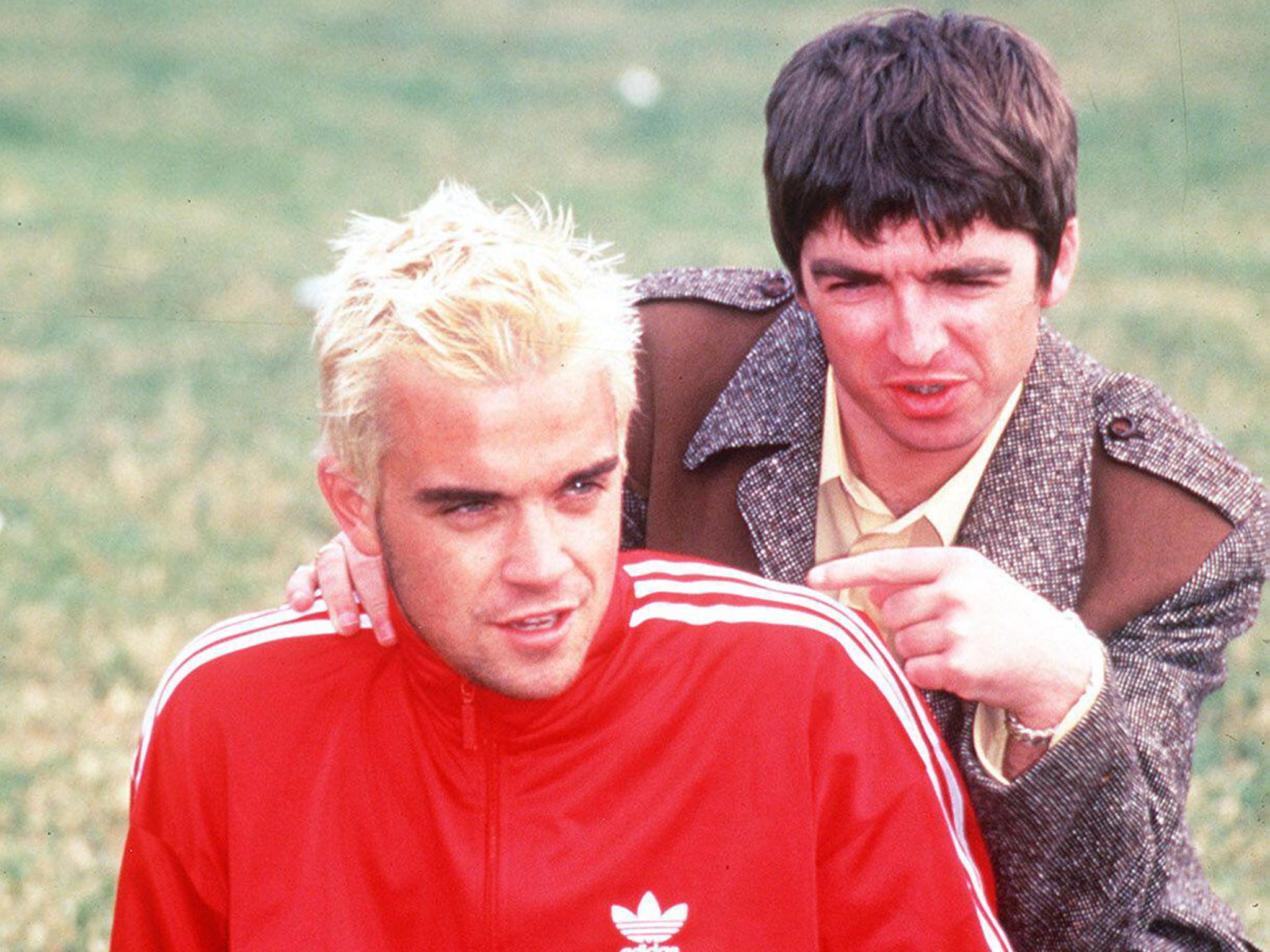

For a more modern show of the sting that words can carry, Robbie Williams recently spoke of having left the country to escape the verbal taunts of the Oasis brothers. He remembers “every single syllable of every single thing they’ve ever said about [him]”. He still despises Noel Gallagher. “Isn’t it interesting,” said Williams, “what a few words can do to your whole life? I’m not healed.” It gives resonance to the lyrics from his hit “Feel”: “I need to feel real love and the love ever after – I cannot get enough.” This is not to mention the reality stars who have taken their own lives in part owing to what was written and said about them in the press.

Words hurt. Those of us harking nostalgically back to an uncensored utopia are actually pointing to something else. It’s not that words didn’t hurt us – it’s just that the ones that did were different.

I recently interviewed linguist Professor John McWhorter. His book, Nine Nasty Words, traces the roots of English swear words and offensive imagery. What fascinated me was that, while the left hemisphere of our brains lights up for language, it is the right side that beeps and bops around swearing.

I suspect that mine – and many of yours – prickled upon hearing Holocaust to describe football. You may have even felt a physical pang. This convulsion comes from the neurons activated on the right side of your brain’s hemisphere, far from the realm of mere language. It indicates that there really is something physical about offensiveness that exists beyond language. Swear words can even subdue pain, allowing test subjects to keep their hands in freezing water for longer.

As for which particular words tickle those sensors, it depends. Our F-word, S-word and C-word might do little to a French person (Frenchman avoided lest it fall foul of identity sensibilities), whereas I’d wager putain and merde will be allowed to stand naked in this English-language publication.

In my twenties, I lived and worked as a journalist in several countries, and learned to speak five languages. And while I did all I could to acclimatise to each new setting – even repeating words over and over in vain to get the accent down – I withdrew from one central tenet of the language: swearing. (That is, apart from my initial mispronunciation of “merci beaucoup” as “merci beau cul”, which veers towards the profane.) I punctuate most of my sentences in English with swears, but it felt wrong to do so in foreign. At the time, I wasn’t sure why this was.

I now believe that it was because the locals in question had more skin in the game. Since the swear words were new to me in French, Spanish, German or Portuguese, they hadn’t yet burrowed their way into the offence-sensitive right hemisphere of my brain. It didn’t feel fair, then, to use words that meant more to them than to me.

This is a great shame, because some foreign curses are wickedly imaginative. But reciting “la concha de la lora” (the parrot’s vagina) in Spanish or “fick die Waldfee” (f*** the forest fairy) in German would probably not have had any effect on the amount of time I could keep my hand submerged in ice water. To use these words in the company of those who did hold these eccentric curses in their right hemisphere felt like an abuse of power.

There is nothing, then, intrinsically offensive about each language’s swear words. It’s just the value each culture and generation apply to them, and how taboo they are in one’s formative years.

Equally, words that offend us now are nothing like those that set off our right-hemisphere sensor decades or centuries ago. Aforementioned linguist McWhorter writes of a shift in offensive words in the last millennium from the theme of religion (darn, heck and hell) to the body (as in the afore-censored swears). In the intermittent period, the two combined. I recently re-watched (and adored) Cinema Paradiso, a movie about that mid-20th-century period of bodily censorship, when kisses were cut from movies by religious zealots. That seems as quaint as it does ridiculous by today’s standards.

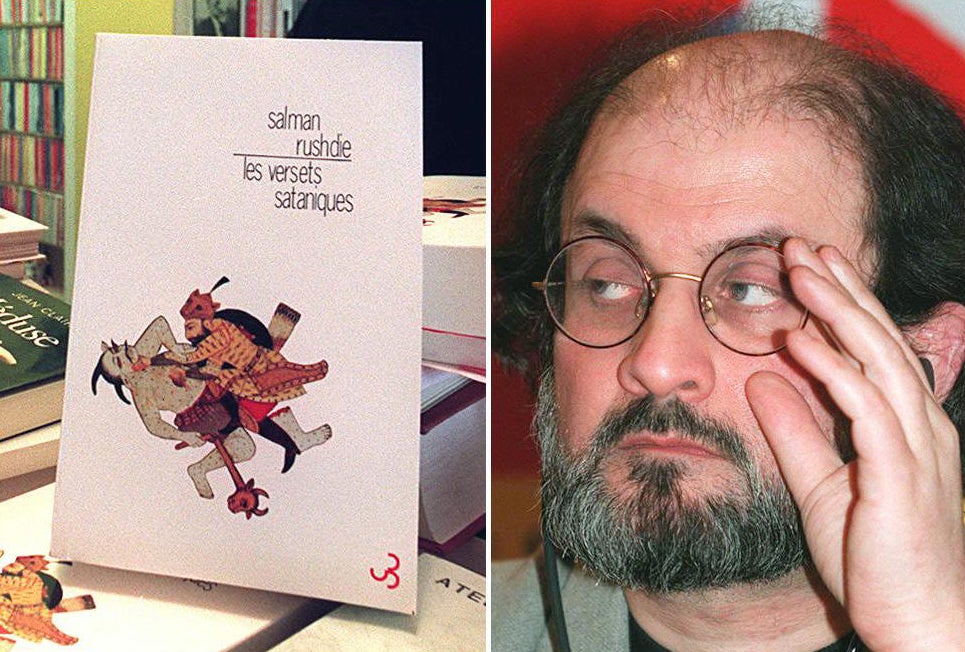

And yet – despite being on the decline for centuries – blasphemy was still an offence punishable by law in the UK until as recently as 2008. Funnily enough, Salman Rushdie’s satire of the Prophet Mohammed in The Satanic Verses wasn’t indictable, because the antiquated law only covered blasphemy against Christianity; not Islam. Still, it can be argued that his transgression did cause offence; he went into hiding for 10 years after a fatwah was declared by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989.

In 1992, secondary school teacher Michael Newman was arrested under said blasphemy law and forced to resign. Near Canterbury Cathedral, he had been caught selling a film called Visions of Ecstasy, the only movie to be refused certification by the British Board of Film Classification due to blasphemy. His punishment, severe though it may seem to us today, is nothing compared to historic indictments of religious transgressions, when blasphemy was considered so offensive as to merit the death penalty.

Thomas Aikenhead was a 20-year-old student in Scotland, in 1697, when he became the last person in Great Britain for whom blasphemy meant execution. He was accused of stating that “theology was a rhapsody of ill-invented nonsense” and that he “admired the stupidity of the world in being so long deluded by [it]”. Sadly, accounts from five of his own friends sealed his fate, and he was sentenced – on Christmas Eve no less – to death by hanging.

There is something physical about offensiveness that exists beyond language. Swear words can subdue pain, allowing test subjects to keep their hands in freezing water for longer

Marking a gradual change in our sensitivity to blasphemy as an offensive theme, Thomas Babington Macauley, a historian born around a century later, wrote of the execution: “The preachers who were the poor boy's murderers crowded round him at the gallows, and ... insulted heaven with prayers more blasphemous than anything he had uttered.” Although Aikenhead was the last to be killed for this sin in Great Britain, it wasn’t abolished as a capital offence in Scotland until 1825.

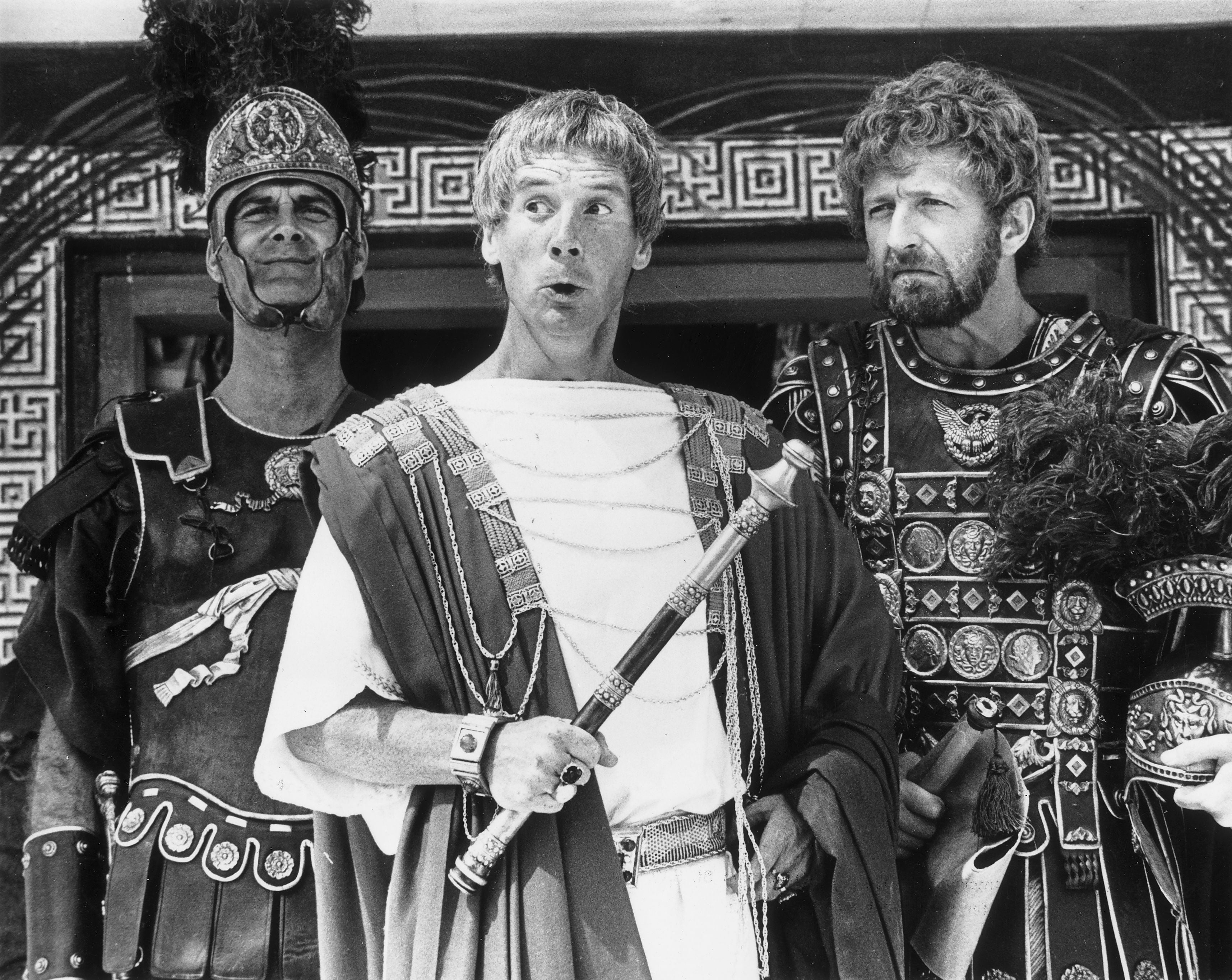

Over time, religious slurs began to lose their power. Monty Python’s Life of Brian movie stoked furore when it came out in 1979. Yet, the actors and writers weren’t cancelled or impeded by the film (nor were they arrested and hanged), but rather lifted to new heights of celebrity. With religion becoming less significant in the realm of offence, they were able to use the controversy to their advantage. Take this marketing slogan in Sweden: “So funny, it was banned in Norway!”

Ireland and Italy also pulled the film, and it was given an X certificate and banned in some British cinemas. For its 2019 re-release, Life of Brian was granted a 12A because of “six uses of strong language”. Religion and blasphemy don’t get a mention in the decision. In the past few decades, sex has also become less offensive, with exposed flesh melting on to our screens, culminating in a splurge of bodily gratuity in the likes of Naked Attraction and Love Island.

We still have fun with those naughty images and words, and continue to censor songs and swears on the radio and TV, presumably lest children be contaminated by such words. And while blasphemy laws have been abolished, you can still be arrested for swearing in the street.

West Yorkshire Police state: “The effect on others and the intention of the person swearing would be some of the factors to consider.” Another is the “annoyance of residents”. Even so, sex swears don’t hold the power they once did, and even the C-word – though I daren’t spell it out – has become a synonym for “mate” in the UK. With sex-related swears losing their authority over the past decade, we brought offence into a new realm: identity.

Today, the most offensive words and images are those that contravene identity lines. It’s why trans issues and BLM are front and centre, while those who transgress, such as JK Rowling, are cast out. As the Harry Potter writer has a new book out, you might argue that cancel culture is a myth or that it only truly works on smaller fish.

In any case, she has caused a level of offence unimaginable for the crossing of identity lines just a decade or two ago, leading to death threats and door-stepping the likes of which was previously reserved for blasphemers (see Rushdie). Even cricket can be catapulted to the front pages by identity. And Barton’s offensive use of a word – Holocaust – related to an identity was enough to suggest he be fired, and to divert some of the attention from his trial for physically assaulting another manager.

He was later found not guilty. But here’s the thing about Barton. This is a man who stubbed out a lit cigar in a youth player’s eye. He broke a pedestrian’s leg while driving through Liverpool at 2am. He picked up £120,000 in fines for various misdemeanours in one season before seeking anger management treatment. And he was arrested for allegedly ripping out the radio of a cabbie who refused to wait for him to get food at a McDonald’s. The list goes on.

So, no one was really surprised that he said or did an offensive thing. His behaviour – insulting to the memory of those who lost their lives in the Holocaust – is hardly unexpected. What did come as a surprise, however, was that Barton showed some acuity in his apology: he blamed the “modern day world we live in” for the furore that followed his insensitive words. This is not to minimise suffering at the hands of identity-motivated harassment, but merely to track the shift in what is deemed sacred, and wonder where it might lead next.

That I’ve used as a jumping-off point for this article a reference to Jewish identity transgressions is no accident. Such is the sensitivity right now to offence around identity that I’m reluctant to express opinions on controversial issues outside of my own. Escorting this move towards identity politics is an emphasis on “lived experience”, and mine only extends as far as “Jewish man” (though I’m an atheist, and not particularly virile).

Lived experience marks a progressive shift in focus, enabling us to amplifying the voices of marginalised groups not previously heard. It also has drawbacks. Lived experience can favour subjectivity and emotionally loaded discourse over reason. It can also be used for nefarious means, as was the case with countless social media accounts during the Corbyn antisemitism scandal who began posts with “as a Jew”… only to then express what could be interpreted as anti-Jewish sentiments. These accounts were often found to be owned by people who were not Jewish, sparking in response (by those who noticed) the satirical hashtag #AsAJew.

Despite the limitations on acceptable discourse with respect to identity right now, it can be argued we live in one of the most liberal times in history

Also, there is a tendency in the progressives among us to only accept lived experience as evidence when it suits us. When Caitlin Jenner stated she didn’t think trans women should compete in women’s sports contests – an unpopular opinion among many liberals – Sarah Silverman, a talented and progressive comedian, put up a video slamming Jenner. But progressive identity rules around lived experience dictate that Jenner – not only the world’s most famous trans person, but also a revered former Olympic athlete – holds the trump card in this debate. The problem is, she also holds a Trump card, in that she’s a Republican, which puts progressives in a bit of a pickle.

Another effect of this focus on identity is an increase in tribalism and staying in one’s lane. Actress Tamsin Greig recently expressed that she regretted playing a Jew in comedy series Friday Night Dinner. I found this incredibly sad, because she did such a wonderful job portraying a particular type of person that I, (#AsAJew), knew well growing up.

In fact, such was my shame around being Jewish as a child that I adored any non-Jewish actor who took the time to get inside the head of a Jew. I recall my admiration for Robert De Niro growing, when I was in the cinema for a re-showing of Once Upon a Time in America. Even after his character committed one of the most violent rapes ever shown on film, I found myself relieved he considered a Jew – even a psychopathic rapist Jew – human enough to inhabit. Looking back, I recognise that this is sad and, perhaps, problematic (a word to describe offensive language whose use has grown by 1,300 per cent since the 1970s according to Google’s etymology programme).

There are also many positives to take from today’s sensitivity around identity. If we must nominate taboos, surely immutable identity is a worthier candidate than religion and sex? From being vastly under-represented, black and minority ethnic (Bame) individuals now make up 23 per cent of onscreen actors and presenters according to the industry-standard Diamond Diversity Report. Bame people make up just 13 per cent of the UK population, so this bodes well; although the prominence of said onscreen roles for minorities is unclear.

Even football stadia – some of which were once targets for BNP leafleteers – are now hubs of inclusivity. Just the other week, I saw Spurs’ stadium lit up in rainbow colours to honour the LGBT+ community. Who’d have seen that coming just a few years ago? Some might say this is worth me missing out on getting to see the likes of Tamsin Greig playing a Jewish mother… even if she did do a truly wonderful job.

Despite the limitations on acceptable discourse with respect to identity right now, it can be argued we live in one of the most liberal times in history. Those of us who wince at identity censorship should rejoice in the sexual and religious/atheistic freedom we experience today. McWhorter believes that this focus on identity too shall pass. When I quizzed him on what could replace identities at the heart of offence, he put forward climate change as a potential challenger. “Perhaps in 50 years,” he half-joked, “you’ll call someone you dislike a windmill.”

The musical chairs of offence will alter the way many of us perceive Joey Barton in the future. In some ways, this was an exercise in PR management. If identity falls from the limelight, Barton might be remembered for a stupid choice of words, rather than stabbing a cigar in his teammate’s eye and allegedly assaulting a taxi driver.

You could even argue that it strikes a positive note that – in a world rife with Holocaust deniers – Barton equated the genocide with something he perceived as bad rather than made up. It’s also promising that he apologised (ifs and buts notwithstanding). Personally, I believe he regretted using the word “Holocaust” the instant it left his lips, swiftly searching for synonyms under which to submerge it: “A nightmare, an absolute disaster.”

That said, such is the sensitivity around identity at the moment that to let these moments pass without taking offence feels like exceptionalism. And Jews are sensitive to rules that exclude them; the offensive word in question is a constant reminder as to why. They have reason to be concerned too. That the word has been used twice so glibly in public suggests a growing trend in private. Its use serves to downgrade the measure of the Holocaust to that of a rubbish football game. And that’s bad news for Jews, the next time they face a tricky fixture list.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments