The case against reality: Does what we see exist?

Chris Horrie attempts to answer one of the longest-running unanswered questions in philosophy

Do we see reality as it actually is? Well, unless you are currently in a state of complete mental breakdown or in the midst of an LSD trip (or both), then you are almost certainly going to answer this question with a categorical: “I don’t know. Do I?”

One reason you can respond in this manner is that you are a human being and not an Australian jewel beetle. The males of this benighted outback species have lately been rocketed into the centre of both philosophical speculation and big dollar Californian computer science because they were so certain that they were seeing reality – beetle reality that is – “as it actually is” that it brought them to the point of extinction.

As Franz Kafka once observed it is both dangerous and extremely unpleasant to place yourself inside the mind, let alone the body, of an insect. But as far as we can tell the picture of reality evolved over countless thousands of reproductive cycles by the flying male jewel beetle is centred on finding the flightless shiny, brown, dimpled glass-like females of the species and covering them in beetle sperm until dying from exhaustion. They will then make way for the next generation – some of whom, hopefully, will be mutants. All of this may not seem very edifying. But in evolutionary terms, it’s a living.

Read More:

Then along came humans littering the beetles’ habitat on the edges of campsites with casually discarded brown beer bottles, affectionately known to locals as “stubbies”. These bottles had the same look as the female beetles. But the bottles were much bigger and therefore, in the male beetle’s assumed picture of reality, much sexier. In fieldwork two entomologists from the University of Toronto reported seeing male jewel beetles ignoring females of their species and instead landing on the 375ml brown bottles where they would attempt to copulate furiously until collapsing with heat exhaustion. Weakened in addition by starvation, they would fall off the bottles to be eaten alive by grateful killer ants. In the end the beetles were saved by the brewers who changed the design of their bottles.

But what if the beetles had somehow been able to see the “reality” of the beer bottles, thus recognising the tragic mistake they were making? You or I might be freaked out of an unexplained bump in the night, or the sudden appearance of a creepy and unfathomable obelisk from another dimension in a psychedelic Sixties sci-fi film. But what would beetle make of a bottle? It would surely come as a hell of a shock. And what if we are just like those beetles – possessed of a picture of reality held with equal conviction but being just as flawed. What if right now while you think you are looking at the screen of an electronic device, what is actually there is as different and unimaginable as a beer bottle is to a beetle.

* * *

Most people perverse enough to wonder about these things are reputed to think that reality is “out there” as a series of objects which we examine with our senses – the eyes, in the case of sighted people, functioning like cameras relaying a more or less accurate picture of the world which is then processed by the brain.

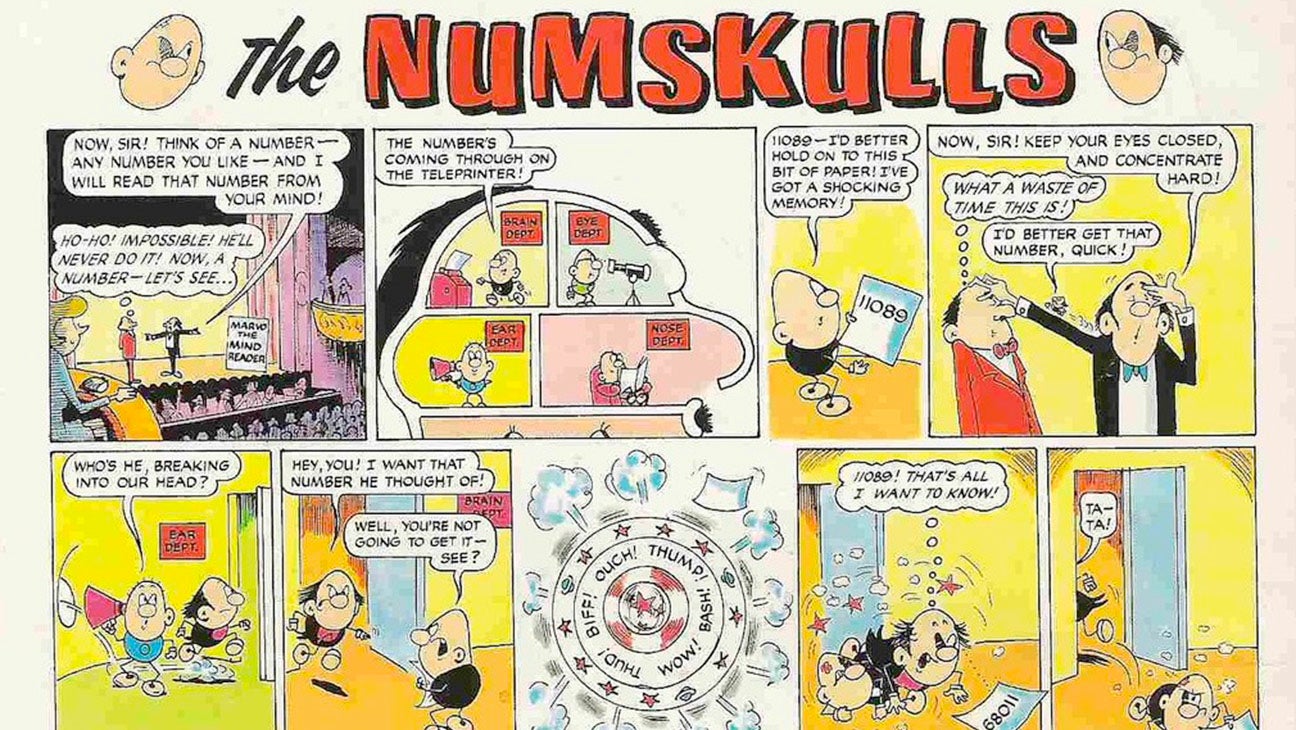

This theory of perception was perhaps best illustrated not by a philosopher but a cartoonist – Malcolm Judge, author and artist of “The Numskulls”, the long-running and unfailingly hilarious cartoon strip in The Beano. In the strip teams of tiny humanoid mechanics live inside the heads of various gormless youths (and once, in a special guest appearance, Ant and Dec), guiding them through a series of potentially embarrassing slap-stick situations. The Numskulls are led by Mr Blinky who sits in the eye sockets of the skull which function as windows. Ironically Mr Blinky is extremely short-sighted. He spends time squinting myopically through his jam-jar specs at the exterior world, periodically feeding misleading reports through to his boss – Mr Brainy – who sits in a windowless office towards the back of the skull operating a computer and looking extremely pleased with himself. In line with philosophical tradition females play no role whatsoever in the processes of either perception or thinking, even in these enlightened times.

The Numskull model is not a bad guide to the way in which philosophers thought the mind worked until comparatively recently. This was a system of philosophical dualism in which a conscious soul inhabited a machine-like body, entering it at birth and departing at death. These days mind-body dualism is well and truly out of fashion, replaced by a system of philosophical monism whereby the mind is seen as part of the body, or as a function or even a consequence of the body’s organic processes. The obvious problem with mind-body dualism was working out how the mind was connected to the body, and how it could cause or direct physical action.

The abandonment of dualism more than a hundred years ago however led to another and, if anything, even more intractable problem: the question of how thoughts and a sense of being can arise from the unconscious grey matter of the brain. This is the so-called “hard problem” of consciousness, and it is as much a mystery as it was at the dawn modern philosophy some 300 years ago.

Where knowledge had greatly increased in recent decades is in the mapping of neural activity in the brain, using scanners and evidence from brain surgery to detect the correlation of electrical impulses around the brain with mental states, moods and emotions.

One surprising finding is that only a relatively small part of the brain is directly involved in processing vision in the sense of stimuli from the outside world. Thus as you read this article about 127 million receptor cells in each of your eyes are being stimulated by the light from the screen. This sounds like a lot, but at the same time billions of neurons and trillions of synapses are firing simultaneously – probably a thousand times more processing capacity than would be needed to record and store any sort picture of the world analogous to a digital camera and computer memory chip.

If I exist only in somebody else’s mind, what happens to me when nobody is looking at me?

The question is what are all these apparently redundant synapses doing? Whatever it is takes up a lot of energy; the average brain burns around 500 calories a day, which is up to a quarter of the total energy consumption of the whole body at rest. It is very unlikely that humans would have evolved in competition with other species if that sort of expenditure of energy were wasted. The answer according to contemporary conventional scientific wisdom is that all this processing power is being used to generate and maintain a complete picture of the world which we use to navigate around it. Fresh information from the eyes and other senses might be used to update or amend this picture or 3D map of the world, but it is not entirely dependent on this information, as in the old Numskull-type model.

Now a multidisciplinary team of mathematicians, brain and computer scientists led by the cognitive psychologist and philosopher Donald Hoffman of the University of California, Irvine, have gone one step further, claiming that the picture of “reality” produced by the brain is not merely semi-independent from reality as perceived by the senses, but is produced to deliberately obscure reality. Instead the mind produces a series of “dumbed down” icons or sensory clichés which are useful for survival and reproduction, but are not any sort of accurate representation of underlying objective reality.

The notion that things only exist in the mind is an old and popular idea, dating back at least to ancient Greece. The theory seems to solve a lot of problems – not least the origins of time and space. No need to worry about those things. They neither were present, so far as you are concerned, before you were born they and will disappear at the moment of your death. It’s a neat theory, but it also raises immediate objections: what happens to objects when nobody is thinking about them? If I exist only in somebody else’s mind, what happens to me when nobody is looking at me? And how come it hurts so much when I stub my toe on an object like a table leg which exists only in my mind?

The philosopher Immanuel Kant came up with an ingenious solution to this problem. Kant speculated that objects have different natures depending on whether they are being observed or not. When an object is being perceived it becomes “a phenomena”, which is to say an object in the mind. When it is not being perceived it exists in a different form. It is a “noumena” or “thing in itself” existing independent of anyone’s mind. Whereas we can examine and measure phenomena in great detail, noumena or “things in themselves” are entirely unknowable and therefore not worth bothering about too much (except by artists, poets, theologians, musicians and other ethereal types).

Kant was so pleased with this argument that he called in the Copernican Revolution in philosophy. Just as the astronomer Copernicus had turned things upside down by showing that the Earth circulated around the sun, and not the other way around, Kant had shown that the physical world arose from ideas, overturning the more intuitive notion that ideas arise from experience.

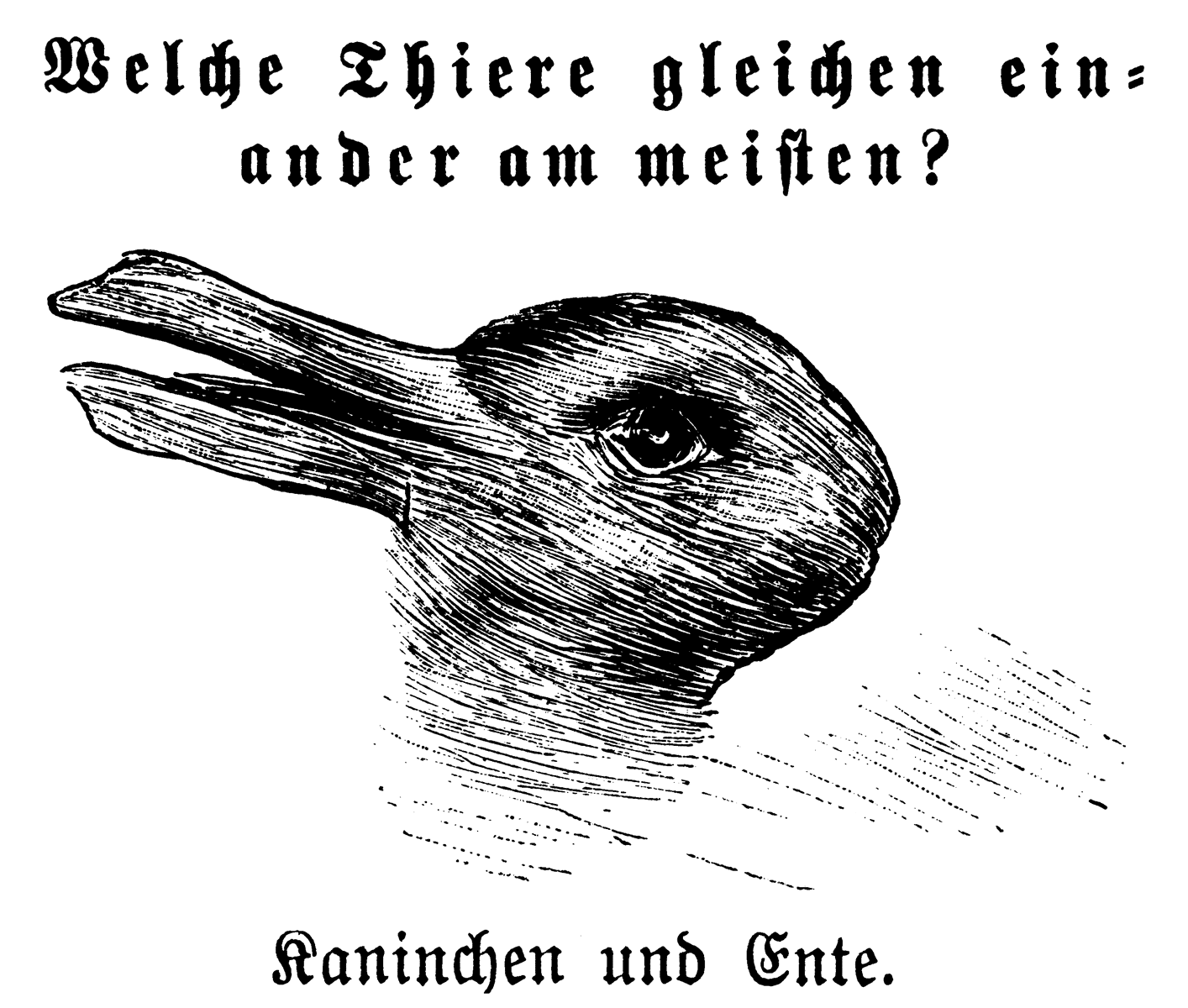

Doubtless Kant was seen by many at the time as barking mad, the same accusation levelled against Copernicus and his loony Earth-goes-round-sun nonsense when anyone with common sense can see that it rises and sets every day. But two centuries of scientific endeavour have shown him to be essentially right. In particular Einstein’s theories of relativity – which show that physical objects change their nature when they are observed by the very act of being observed – added lustre to Kant’s stature as one of the founders of modern science. In more recent decades a mountain of evidence from experimental neuroscience, psychology and brain surgery has given further credence to the notion that what we see is not merely filtered or distorted by the brain from data gathered from the external world, but is created inside those grey coils completely or with minimal input from the senses. Some of the best-known examples include phantom limb syndrome whereby amputees report sensation and action in their missing arms or legs, psychedelic experiences and optical illusions such as the duck-rabbit drawing made famous by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

If you look at the drawing you are likely to see either a rabbit or a duck, but not both, at the same time. Once you have seen the rabbit (or duck) you cannot, however, unsee it and form a stable picture. Your idea of what the object is will switch between the two. Nothing in the external world is changing as you view the drawing. The duck-rabbit is therefore used to show how the nature of things is dependent on how they are perceived, and how they fit into the consciousness structure of the observer, rather than what they are as things in themselves.

Until now neuroscientists and philosophers have been reluctant to throw out the noumenal baby with the phenomenal bathwater entirely. Undergraduates are still taught that things we see or hear are actually “out there” in some form, however distorted and that more accurate microscopes, telescopes and scanners will produce an ever more accurate picture of the world as it is. The conventional proof is that accurate perception through the senses must convey some sort of evolutionary advantage – those of our ancestors who saw more clearly or heard things more clearly and this enabled more of them to survive and pass on their genes to us.

Donald Hoffman is the first major voice in the US west coast computer science/artificial intelligence community to abandon this view entirely, arguing that evolution towards an increasingly accurate picture of reality would produce a disadvantage and not advantage in evolutionary terms.

Hoffman first came to international attention in 2015 with the publication of his book The Case Against Reality, subtitled “How evolution hid reality from our eyes”. Hoffman explained his central idea in an interview at the time of the book’s publication: “An organism that sees reality as it is will never be more fit than an organism of equal complexity that sees none of reality but that is just tuned to fitness.”

Hoffman began his research in the MIT computer science department where he worked across the disciplines of computer science and philosophy, following an interest, from philosophy and psychology, in the nature and origins of consciousness. His expertise in computer science led to an interest in artificial intelligence and the whole issue of whether or not machines could ever become conscious in the same way as humans.

The originality of the argument in The Case Against Reality comes from the application of solid laboratory experimentation and mathematical modelling to the framework of ideas inherited from Kantian philosophy. Hoffman began by modelling the evolution of consciousness not by speculating as a philosopher might do, but by developing mathematical algorithms predicting which factors would be more or less likely to lead to evolutionary success. By the end of 1990s these models were extremely sophisticated.

Space and time, as you perceive them right now, are your desktop. Physical objects are simply icons on that desktop

But as he added detail he came to a shocking conclusion: evolution never led to an increasingly accurate picture of external reality. Hoffman says he was so startled by this conclusion that he had to sit down and compose himself. He then set out to check his theory by running thousands of computer simulations in the lab.

The Case Against Reality summarised 30 years of experimentation in labs running thousands of computer simulation modelling “robots” programmed to compete a sort of computerised version of The Hunger Games, where the aim was to mimic biological organisms of various types and win the resources needed to survive and reproduce. Some of the robots were able to see all of reality, at least as humans think of it, such as space and time. Others were only able to perceive part of reality, and yet others none of reality at all. All however were programmed to perform “fitness behaviours” that would enable them to survive. As result he claims to be able to prove with mathematical precision that the belief that we possess an accurate picture of reality, or essentially a picture which can be improved and perfected by more accurate observation, is not only false, but that it is a positive disadvantage in terms of evolution.

Fortunately humans have evolved an entirely inaccurate picture of reality even though very few of us are aware of this fact. What we think of as reality, he says, can thus best be likened to an “interface” with reality, like the screen you are most likely looking at right now on a digital device of some sort, and not reality itself. The icons and graphics you see on your phone or computer function in exactly the same way as our sense of objects in the real world. Those icons and symbols produce “fitness payoffs” in the form of messages sent, or processed information or experiences received, and not information about the reality underlying that information.

Hoffman gives the example of a pet cat. The fitness pay-off of the cat is the important psychological benefit of stress relief, the sense of purpose or egotism you derive from petting it. The reality of the cat however – if only we had eyes powerful enough to see it – is a terrifying and revolting chaos of parasite-infested exploding protein molecules, surging blood and hormonal fluids and other horrors. At a lower level yet the “cat” consists of bizarre, electrified chains of molecules, atoms, electrons, quarks and god knows what else, separated proportionately by amounts of empty space so vast that you would conclude that your pet is 0.01 per cent sickening biochemical killing zone and 99.09 per cent howling void. And so, we ignore reality and just think of this mess as “my cat”. As Hoffman points out in an interview the computer industry spends billions in covering up the reality of the workings of computers and producing an illusory world of icons and desktops, wastepaper baskets and letterboxes which are nothing of the sort. As Hoffman puts it: “Space and time, as you perceive them right now, are your desktop. Physical objects are simply icons on that desktop.”

Read More:

This part of the argument prompts an obvious objection – if something like a train is not really a train, but merely a mental picture of a train, why not jump in front of it and see what happens. Hoffman’s reply is that an orientation towards reality would lead you to wonder whether or not the train was moving fast enough to reach you, what it was made of, how likely it is that it could harm you. However, we have evolved a “dumbed down” icon of a train that just says, “do not stand in front of this thing, even if it not moving”. The person who relies on the icon will survive to have kids. The person who investigates reality will die.

Last month Hoffman published further analysis of the lab results in peer reviewed journals, further tweaking his algorithms. This work, he says, proves with mathematical precision that the probability of our picture of reality corresponding to any sort of external reality is “exactly zero”. Agents Mulder and Scully of the recently rebooted X-Files TV series might claim that the “The Truth is Out There”.

But Hoffman will reply: “Oh no it isn’t.” And now he has the maths to prove it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments