The fate of the language: How Wales found its voice again

In the 20th century, Wales struggled for its identity, but soon the decline of the Welsh language halted and the country began to assert itself once more, writes social historian Richard King

During the final four decades of the 20th century Wales witnessed the simultaneous effects of deindustrialisation and a struggle for its language and identity. The country’s voice fought to be heard outside its frequently tempestuous borders and was argued over within them, as the people of Wales underwent some of the nation’s most traumatic and volatile episodes: the disaster at Aberfan; the inundation of Capel Celyn in the Tryweryn valley to create a reservoir for Liverpool; the rise of the Welsh-language movement and its policy of direct action; the Miners’ Strike and its aftermath; and the vote in favour of partial but significant devolution.

This history of Wales begins in 1962, with a radio speech delivered as a warning that Cymraeg (the Welsh language), and the identity and way of life it represented, faced extinction. Titled ‘Tynged yr Iaith’ (‘The Fate of the Language’), the speech was given in the form of a radio broadcast by its author, Saunders Lewis, the former leader of Plaid Cymru. The impact and influence of the speech have long been debated; what is certain is that Lewis’ polemic contributed to a renewed sense of purpose among those resistant to the language’s increasing marginalisation.

Over the subsequent three decades the case for Cymraeg would be campaigned and argued for with an applied fervour. In 1990, Welsh became a compulsory subject for all pupils in state schools in Wales up to the age of 14. Three years later the Westminster government passed a Welsh Language Act, which formally recognised that “in the course of public business and the administration of justice, so far as is reasonably practicable, the Welsh and English languages are to be treated on the basis of equality”.

As the decline in the language was gradually halted, the industrial centre of South Wales – the area in which over half of the country’s population lived and worked and where the Welsh language was heard less frequently than English – entered into a moderate then accelerated decline of its own. The heavy industries of steel, oil and mining were all significant employers in the region; the centre of the last of these was the South Wales Coalfield, home to the historic communitarian radicalism fathered by the Miners’ Federation and its welfare institutes and libraries. The libraries, the Manic Street Preachers would sing, “gave us power”. In the year of Lewis’ radio lecture, a job in heavy industry offered above-average terms and wages in a form of employment that had strong links with the area in which the work was based. As well as payment in exchange for labour, the work provided social capital. In these close-knit communities, employment was ingrained with identity, an attribute that grew in significance during the increasing secularisation of Wales that had gained momentum by the 1960s.

Wales consequently experienced a period lasting almost 40 years in which two distinct energies animated the country. The first derived from an often youthful, determined movement dedicated to the survival and revival of Cymraeg; the second energy came out of a crisis, one not limited in this period to Wales nor any of its regions, but one the country, due to its reliance on heavy and light industry, experienced acutely: an initially gradual then substantial reduction in remunerative long-term employment opportunities.

The country’s political and legislative authority, such as it was, was held in the Labour stronghold of the south, a part of Wales that often considered itself to be as British as it was Welsh. Here, in the offices of MPs and powerful, usually male-dominated council chambers, concerns for the fate of the language and the ideas of Welsh independence proposed by Plaid Cymru in the west and north-west of the country were marginal issues. Such concerns were at best dismissed as student politics. For much of this period, in the eyes of South Wales Labourism, a self-governing Wales was a cause proposed by dangerous nationalists, or “Nats”. The country was accordingly often forced to navigate its way through a period of great change in a state of internal contradiction and frequent animosity. This history concludes with the vote for Welsh devolution in September 1997, held five months after the Labour Party had been returned to government in the UK for the first time in 18 years.

The new Cardiff government had created an opportunity, to say nothing of the challenge, to formally embed environmentalism and community resilience into Welsh society

The vote was carried by a majority of 6,721, or 50.3 per cent of the vote, among the narrowest of margins in British electoral history. The country nevertheless voted for the limited form of self-determination represented by the creation of a National Assembly for Wales.

The National Assembly for Wales was established at great speed with little preparation. Despite the narrowness of the “yes” vote victory, the losing side accepted the outcome with good grace, to such an extent that leading members of the “no” campaign were happy to stand for election and duly took up positions as assembly members.

In 1999 the inaugural assembly administration was a Labour-led minority government which focused its energies on greater accountability of the delivery of public services; in 2000 the Labour Party entered coalition with the Liberal Democrats. For any unreformed devolution sceptic, the argument that the assembly would be little more than an enhanced version of a managerialist mid-Glamorgan Labour council seemed irrefutable. The assembly was a form of government that struggled to assert itself in the popular consciousness.

Despite such perceptions, the assembly demonstrated a willingness to assert a bold vision of Wales. It was an outlook that befitted an administration that was taking power on the cusp of a new millennium; in 2000 the assembly passed a policy into statute entitled “Learning to Live Differently”. It was a radical piece of legislation. It stated:

The assembly takes the view that our current way of living is unsustainable, and that real progress can no longer be gauged by standard measures of economic growth alone. We believe that economic growth can and must be pursue in ways that are conducive to a sustainable Wales . . . to fulfil its legal obligations, the principles of sustainable development must be mainstreamed into the way the assembly operates.

The new Cardiff government had created an opportunity, to say nothing of the challenge, to formally embed environmentalism and community resilience into Welsh society. The means by which this legislation could be transposed from the statute book into people’s everyday lives remained unclear. Most of the country’s population regrettably remained unaware of the assembly’s aspirations. The prospect of Wales “learning to live differently”, beyond its new, Richard Rogers-designed assembly buildings in Cardiff Bay, was remote. The assembly’s failure to communicate these principles was an early example of the institution’s inability to explain its function or to engage with its constituency. It was a failure that inevitably bred cynicism and disaffection.

The National Assembly for Wales was inaugurated at a time of substantial investment at the hands of the New Labour government, now in its second term, during which the public sector witnessed a rapid growth in job creation. As a result, within five years of being operational, the assembly could point to an unemployment rate in Wales that was lower than the national UK average.

In 2004, two decades after the start of the miners’ strike, Wales had finally staged a form of economic recovery, although levels of economic inactivity in parts of its former coalfields remained high. These areas received substantial expenditure from European Union funds. That their benefits, such as new building and road programmes, skills development and support for business, were rarely appreciated was further evidence of communication failures by the assembly and its civil service, which was regularly accused of taking too piecemeal an approach to distributing funding that might tangibly impact people’s lives.

The Government of Wales Act of 2006 granted the assembly lawmaking powers and oversight of the foundational policies of economic development, health and education. It also strengthened the assembly as an administration, with statutory control of local government, culture, highways, town and country planning and other essential functions of a legislature. These were issues that had to compete with the twin policy responses that followed the financial crisis of 2008 enacted by the Conservative-led government that took office in 2010: austerity and quantitative easing.

At the time of the crisis, Wales’s economy had grown reliant on public spending and the cuts administered from Westminster were felt deeply in communities that had experienced intergenerational poverty. One of the principal functions of austerity was the lowering of expectations about what was achievable in society and of normalising the use of emergency measures such as food banks. Throughout the ensuing decade, numerous reports estimated that up to 30 per cent of children in Wales were living in poverty, the highest levels in Britain.

The growing reputation of Wales as a country with a dynamic and rigorous commitment to environmentalism needed to be reconciled with its continuing, endemic poverty and the speculative, property led economy of South Wales and Cardiff in particular, a city that saw its position in the film and television production industries flourish internationally, even as its relative wealth led to a sense of the capital city decoupling from the rest of Wales. Although property prices in the country remained lower than the national average, the asset inflation that followed the Great Recession as elsewhere further accelerated inequality within Wales. The country became an increasingly popular destination for retirees and for second homes. As the century’s second decade was under way, the tourism industry was, for the first time in Wales’s history, of greater value than agriculture to its economy.

The sector relied on a precarious local workforce employed to clean and prepare rental properties on an ad hoc basis for often absent property owners. These were workers who were mostly unable to purchase homes of their own, in the place of their birth and of their family and communities. Such problems were not unique to Wales, but the enduring impression of a language and culture under threat from aggressive market forces continued to obtain.

For the generations under the age of forty, the battles over Cymraeg that raged in Wales at the end of the 20th century are largely irrelevant

By 2015 Labour had been in power for a decade and a half in a series of coalition administrations, a situation that ensured less continuity in government than the party’s apparent grip on power suggested. Even as its ability to drive through policy was constantly questioned, the assembly continued to create bold and imaginative proposals. That year it published the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act, a law that set out to “improve social, economic, environmental and cultural wellbeing” in Wales.

The Act was designated the lead legislative guide to which Welsh ministers and local authorities were accountable for delivery across the country’s public sphere, including local health boards. Its statutes proposed seven wellbeing goals: a prosperous Wales, a resilient Wales, a more equal Wales, a healthier Wales, a Wales of cohesive communities, a Wales of vibrant culture & thriving Welsh language and a globally responsible Wales. “The past”, Eric Hobsbawm said, “is the raw material for nationalism.” In an increasingly ageing society, one in which substantial assets are held mostly by people over 65, to govern in the name of future generations represented a radical idea.

The Wellbeing of Future Generations Act provided – and provides – Wales with a unique means of constructing a unitary sense of belonging. The ultimate idealised version of Wales, the community of communities that had once existed both in the South Wales Coalfield and Y Fro Gymraeg, was now legislated for as a desirable political destiny. The question of how such a policy might be delivered and such a transformation effected remained unanswered and in practice appeared to be circumvented, or ignored, by many organisations bound by the legislation.

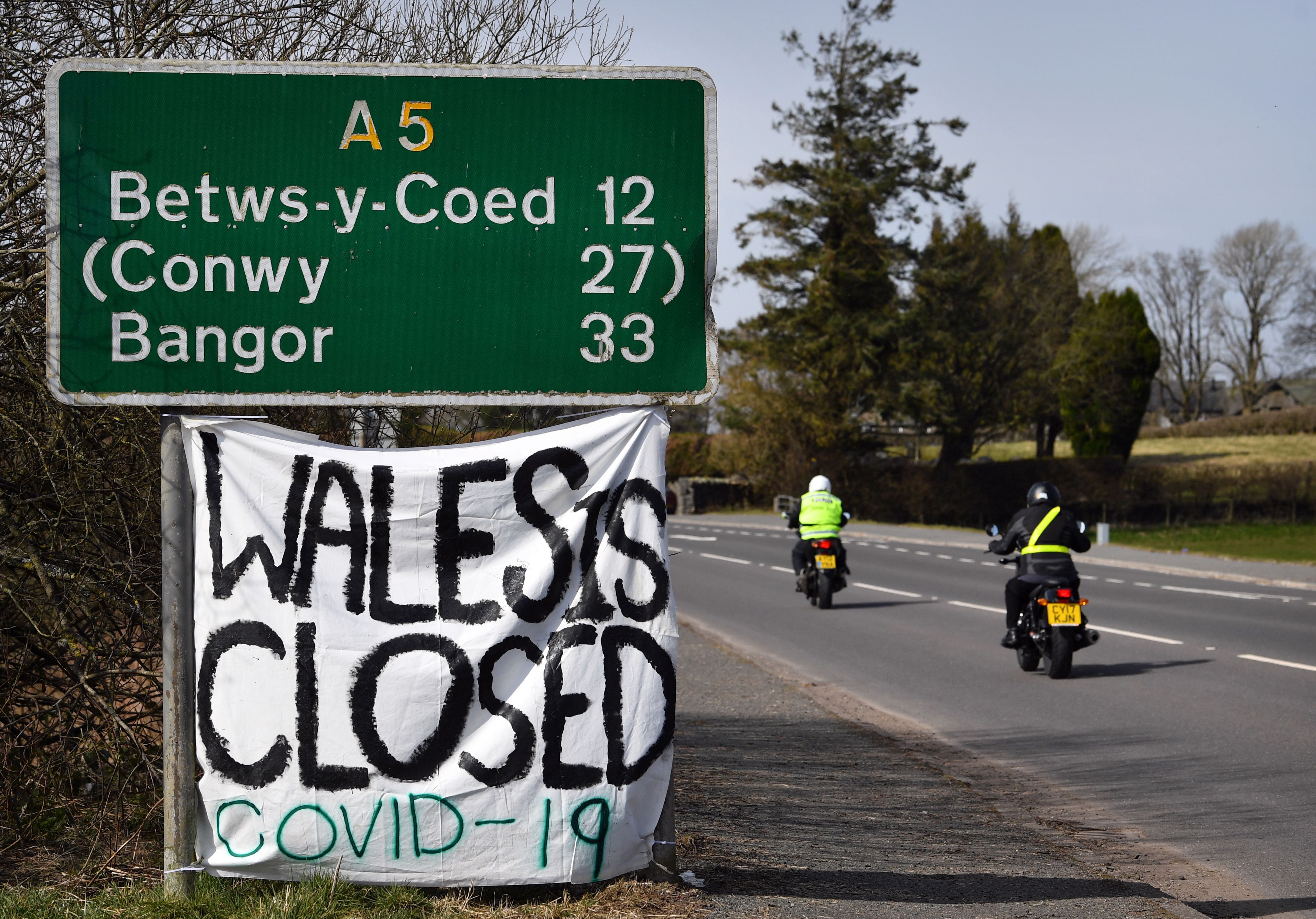

An unexpected opportunity for Wales and the Welsh Government, led since 2018 by First Minister Mark Drakeford, to assert itself and act with a renewed sense of purpose arrived during the global pandemic of 2020. The crisis was the first occasion when many in Wales, and certainly many outside the country, including, it was rumoured, members of the recently elected Westminster government, realised that health and education were devolved matters that fell outside the jurisdiction of London. That Wales could operate independently of Westminster was noted both by its own population and a London government animated by patriotism and the attendant manufacturing of divisive grievances. In the Senedd election held in 2021 Labour, whose manifesto included a commitment to radical federalism, were returned to power with their joint largest vote share.

Wales is a nation that continually discovers ways in which to assimilate its own language into its identity. Today it is common to hear Cymraeg spoken when walking through Cardiff, the capital city that previous generations had to travel across in order to receive a Welsh-medium education. In January 2020 the assembly became officially known as “Senedd Cymru” or the “Welsh Parliament”. Its guidance states that the institution will be commonly known as the Senedd in both languages. A Welsh government now has a Welsh name.

For the generations under the age of 40, the battles over Cymraeg that raged in Wales at the end of the 20th century are largely irrelevant, especially as Welsh history is a subject that features only rarely on any curriculum. A romantic, possibly even sentimental strand of Welsh identity is readily invoked by listing the radical nineteenth century epiphanies of the Chartist Uprising, the Rebecca Riots and the Merthyr Rising. These moments of social insurrection feel more familiar than the miners’ strike, the Aberfan disaster, the drowning of Tryweryn or the campaign attributed to Meibion Glyndŵr, though it was in the shadows of these disputes and crises of the recent past that our future as a nation was decided.

The growth in confidence in the language includes an increased popularity in the use of Cymraeg words that cannot be accurately translated into English. It is a vocabulary that provides a sense of national identity, a quality that has proved to be one of the defining, if accidental features of the Senedd’s first 20 years of existence.

One of the most popular Cymraeg words is the near-ubiquitous “hiraeth”. Its over-familiarity has weakened the charm of its approximate meaning, that of a love of place, or an emotional attachment to a location that defies articulation. It is a word now defined in the Collins English Dictionary and suitable for appropriation by the many indigenous food and drink companies that have been a hallmark of Welsh success and Welsh confidence in the 21st century. Another word in this untranslatable lexicon is “hwyl”. A prosaic definition would locate the word as a Cymraeg equivalent to the Irish “craic”, or the French “joie de vivre”. A richer interpretation might include words such as “passion”, “fervour” or “spirit”. Certainly, the cadences of many nonconformist preachers and those whose oratorial style they influenced, such as Nye Bevan, could be described as communicating with great hwyl.

The origins of the word lie in a much older sense: “hwyl” is the sail of a ship, the means of steering a course. Even in the face of objections to devolution from Westminster, Wales has rarely been better placed to chart a route through any turbulence that threatens the country’s stability. It remains, however, a nation that appears continually to require a renewed sense of self-confidence and self-knowledge from the representatives charged with its governance, to say nothing of the need for a deeper sense of empathy for the population in whose name those elected seek to govern. The ideal of a community of communities is more simply expressed in one word: “people”. And it is the people of Wales who not only understand but define the true meaning of the word “hwyl”.

The following article is an extract from ‘Brittle With Relics, A History of Wales 1962-1997’ by Richard King and is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments