The story of Putin, as told by those in the room with him

Samuel Lovett speaks to diplomats, political aides, journalists and academics who have all met Putin over the past 22 years and witnessed his evolution

As an autocrat who has kept himself at arm’s length from the west for much of his administration, Vladimir Putin is a difficult man to get close to. Outside of the inner circle of Kremlin officials, oligarchs and Russian strongmen, there are few individuals who have shared a room with him. However, there is a small minority of westerners that can claim to have observed and engaged with the Russian president in close quarters, developing a rare first-hand impression of Putin.

These diplomats, political aides, journalists and academics have all met Putin on numerous occasions over the past 22 years, witnessing the evolution of a man and mind that, through the invasion of Ukraine, has come to reshape the modern world.

Here, The Independent tells their stories:

‘The small, unassuming bureaucrat’

As the British ambassador to Russia between 2000 and 2004, Sir Roderic Lyne was in a front-row seat to witness the rise of Putin and his consolidation of power in the post-Soviet era. He saw the man emerge from relative anonymity to carve out a name for himself and usher in a new period of cooperation for the Russian regime, one that, at first glance, suggested the country was beginning to align itself with the west after years of schismogenesis.

An ex-KGB agent who rose through the political ranks in St Petersburg before later courting favour with Boris Yeltsin, the first president of the Russian federation, Putin arrived on the world stage as an unknown entity – first as prime minister, then as the successor to his boss, who unexpectedly resigned in December 1999.

His ascension came at a time of great transition and turbulence for Russia. Under Yeltsin, the old structures of the Soviet Union had been dismantled, yet the country’s economic, political and international future remained unclear and unstable. War with Chechen separatists in the north Caucasus region had also broken out again, drawing widespread condemnation on account of Russia’s brutal handling of the conflict and the killing of civilians.

One of Lyne’s earliest encounters with Putin took place against this backdrop, in March 2000, when Tony Blair was invited to St Petersburg on an “unofficial state visit” to meet Putin who, despite not yet being formally elected as president, was beginning to personalise relations with the west.

The Blairs, Lyne and other British officials were taken around the grounds and buildings of Peterhof Palace, to the west of the city, shown the famous Hermitage and invited to the premiere of a new production of War and Peace at the Mariinsky Theatre. By all accounts, Putin was on a charm offensive.

“He deliberately chose grandiose settings to impress,” says Lyne. “But he personally was quite nervous at the time, one really sensed that he was the new boy. He wasn't at all sure how to play the leader and he was up against somebody who, by that time, had been prime minister for four years and enormously successful.

“There was a sense he was probing around as to how big political leaders acted and behaved and was almost studying Blair. He was speaking through an interpreter, so it was really his body language. It was the deferential way he spoke to Blair. The sorts of subjects he raised.

“One of the things that struck me during these talks was that he had absolutely no grasp of economics at all. He talked in very old fashioned terms, it was like listening to the old Soviet leaders I used to listen to.

“We got on to Chechnya, too, which was a subject of massive concern in the west. There was a lot of criticism of the way the Russians were conducting it. Putin would become very aggressive and defensive. He would go into a long, very emotional, slightly angry monologue in order to cut off the stuff that he didn't want to answer.

Sometimes when you meet people, you’re magnetised by their presence. Putin had nothing about him. The suit was plain blue. The tie was blue with polka dots. The watch was absolutely plain

“His basic thesis was that the west failed to understand that what Russia was doing in Chechnya was fighting on the frontline against Islamist terrorism trying to get into Europe. He argued that we ought to be much more supportive and not critical of the way they were conducting this war.”

A month later, on a return trip to London, Putin lapsed into another “rambling rant” about Chechnya after a British journalist asked a question about the conflict during a joint press conference with Blair at the Foreign Office.

“That just sets Putin off and he got very angry,” says Lyne. “He gave a very long, highly coloured answer. Blair’s looking very embarrassed. He's just saying how wonderful things are. And then there's this guy ranting and raving about Chechnya. It was that side of Putin coming out.

“I concluded from those early encounters with Putin, and I think this is what I was reporting back to London, that there were two Putins: Putin, the rational pragmatist who was trying to improve Russia. And then the other Putin: very insecure, slightly paranoid, a rough boy from the back streets of St Petersburg, an Ex-KGB officer who had been brought up in and believed in the Soviet Union.”

These flashes of emotion and passion appeared at odds with the unassuming image that Putin had cultivated, whether intentionally, during the early days of his administration. Others who met with him were also taken aback by his lack of charisma, his drab way of dressing, his demeanour and body language.

“There was nothing remarkable about him,” says Lord George Robertson, the former general secretary of Nato from 1999 to 2004. “Sometimes when you meet people, you’re magnetised by their presence. Putin had nothing about him. The suit was plain blue. The tie was blue with polka dots. The watch was absolutely plain. There were no cufflinks. No jewellery. A classical intelligence officer.”

But he, too, remembers the unexpected outbursts, which were more often than not triggered by talk of the old Soviet world that Putin had been forced to turn his back on. “There were moments, which, reflecting now, are more important than maybe we thought at the time,” says Robertson.

“I raised concerns with him about what was going on in Chechnya. Georgia was another topic which had he very strong views on – and Latvia, which has a large Russian-speaking population as well. In these cases, he was much more animated, much more emotional. The calculated demeanour changed. But he was very cool and calm 90 per cent of the time.”

Jonathan Powell, the former chief of staff to Blair, was another figure present during the visit to St Petersburg in March 2000. He similarly remembers a “small, unassuming bureaucrat” who seemed unsure of himself and “insecure”.

“He was certainly quite diffident,” he says. “He didn't talk much. At this stage, he didn’t have complete power. He was prime minister but not president. He was under the umbrella of the Yeltsin family which had chosen to put him into this slot. So I think he was feeling his way.

“But he was more like a clerk than a leader, particularly in comparison with Yeltsin. He was at the opposite end of the spectrum.”

Putin even sold himself in this light, says Mary Dejevsky, an Independent columnist and former foreign correspondent who met the president via the Valdai Discussion Club, a Moscow-based think tank, which, for the past 18 years, has brought together experts from different backgrounds to discuss all things Russia and engage with Putin in a Q&A format.

There is little informality to the annual Valdai conferences, which are held across Russia, but Dejevsky remembers one rare moment of “back chatter” when an American journalist asked Putin: “How do you see yourself as a politician?”

“He shot back immediately, ‘I'm not a politician,’” says Dejevsky. “And so the American came back and said, 'Okay, well, what are you?’ Putin said, 'I'm a technocrat, I'm a manager. That's my job.’”

Despite his solemnity, there was some (attempted) humour in those very early exchanges between Putin and western officials, observers say.

At the Nato-Russia Council’s first meeting, with Robertson as the council’s only chairman, the heads of state and government each had a chance to speak. Then, Robertson recalls: “Putin put his hand up and asked for the floor. I thought if he wants to make another speech, they all will.

“I said ‘President Putin has the floor,’ and he said: ‘Mr Secretary General, you’ve told us that you are the chairman of the council, and you're the chairman of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership council, and you are now the chairman of the Russia-Nato council. Can I suggest that Nato headquarters might be renamed the House of Councils?’

“But the Russian word for councils is ‘Soviet’. The interpreter, who had twigged, said ‘I suppose that you call the headquarters the house of Soviet.’ That caused some consternation, but I declared that President Putin had been joking. And it was a joke, he was clear about that at the lunch following. That was his sense of humour.”

I looked the man in the eye. I found him very straightforward and trustworthy – I was able to get a sense of his soul

In another light moment, Lyne managed to break a “fancy chair” at the Peterhof during the visit to St Petersburg in April 2000, remembers Powell. “Putin threatened to make him pay for it, not entirely as a joke,” he says. “There was slight to menace to what he was saying.”

On the same trip, Putin, not one to forget his roots, also took the British contingency to the back streets of St Petersburg where he grew up as a young boy. “We visited a rather seedy block of flats on the outskirts of the city where he had lived,” says Powell.

“He tells this story, about his time there, which is very illustrative for where he finds himself today. When he was a kid, he hung out on the staircase of these collective flats where you all share a bathroom. The staircases were full of rats and he would go beat them to death with sticks to amuse himself.

“On this one occasion, as he tells it, he’s cornered by a big black rat, and he had it with a stick ready to kill it. The black rat, with no alternative, leapt on to his head, scratched him and ran off. He uses this to say you shouldn't corner people. The trouble now is he's the cornered rat.”

An ‘extraordinary window’ of exploration and co-operation

Between 2000 and 2003, there was growing belief that Putin sought to reform Russia and bring the country in from the cold after years of alienation, distrust and geopolitical instability.

Relations with the UK, in particular, appeared to be improving, as exemplified by the relationship that was deepening between Putin and Blair, who maintained a direct and regular dialogue with one another.

“Because Tony had been the first one to go and see him, he had a very good relationship with Putin,” says Powell. “Putin would on occasion call up and ask for advice and things like that, not on domestic matters, but on international things.”

In one of the early exchanges between the two, Putin told Blair that he had brought in a team of modernisers into the administration with the aim of bringing Russia into the 21st century, remembers Lyne.

“These were very bright people in different government departments, with a remit to modernise the Russian economy. His whole thesis to his own people was that Russia could no longer be a military power and that wasn't the way power worked in the world these days.”

Impressed by Putin’s pitch, Blair agreed to send his own “team of reformers” to Moscow to help deliver on these plans. “I hosted a little visit by David Miliband, who was head of Blair's policy unit, and a couple of others to talk to counterparts in the Kremlin for a couple of days about how you promoted reform within government,” says Lyne.

“We had a lot of these constructive discussions about what you might call his modernisation agenda.”

Even Powell was drafted in to cultivate these blossoming relations and keep the Kremlin sweet. It was agreed he’d have lunch on a regular basis with Putin’s chief of staff, who at the time was Dmitry Medvedev, and, later, the now mayor of Moscow, Sergey Sobyanin.

“So I would go to the Kremlin, and have lunch with him and see other Kremlin officials and talk about foreign policy things and they would come to Number 10. And we would do that in reverse. So the relations with the Kremlin were very good. They were in a completely different place to where they'd ever been before. So there was this opening, that could have led somewhere.

“He appeared to want to reach out to the west. It looked like he wanted to be a reformer.”

Sir David Manning, a foreign adviser to Blair between 2001 and 2003, was present as a note-taker during many of these meetings and conversations with Putin. He describes the period up to the Iraq invasion, in 2003, as a “rather extraordinary window” in which there was “real hope in both London and Washington” that a new “cooperative relationship” could be established.

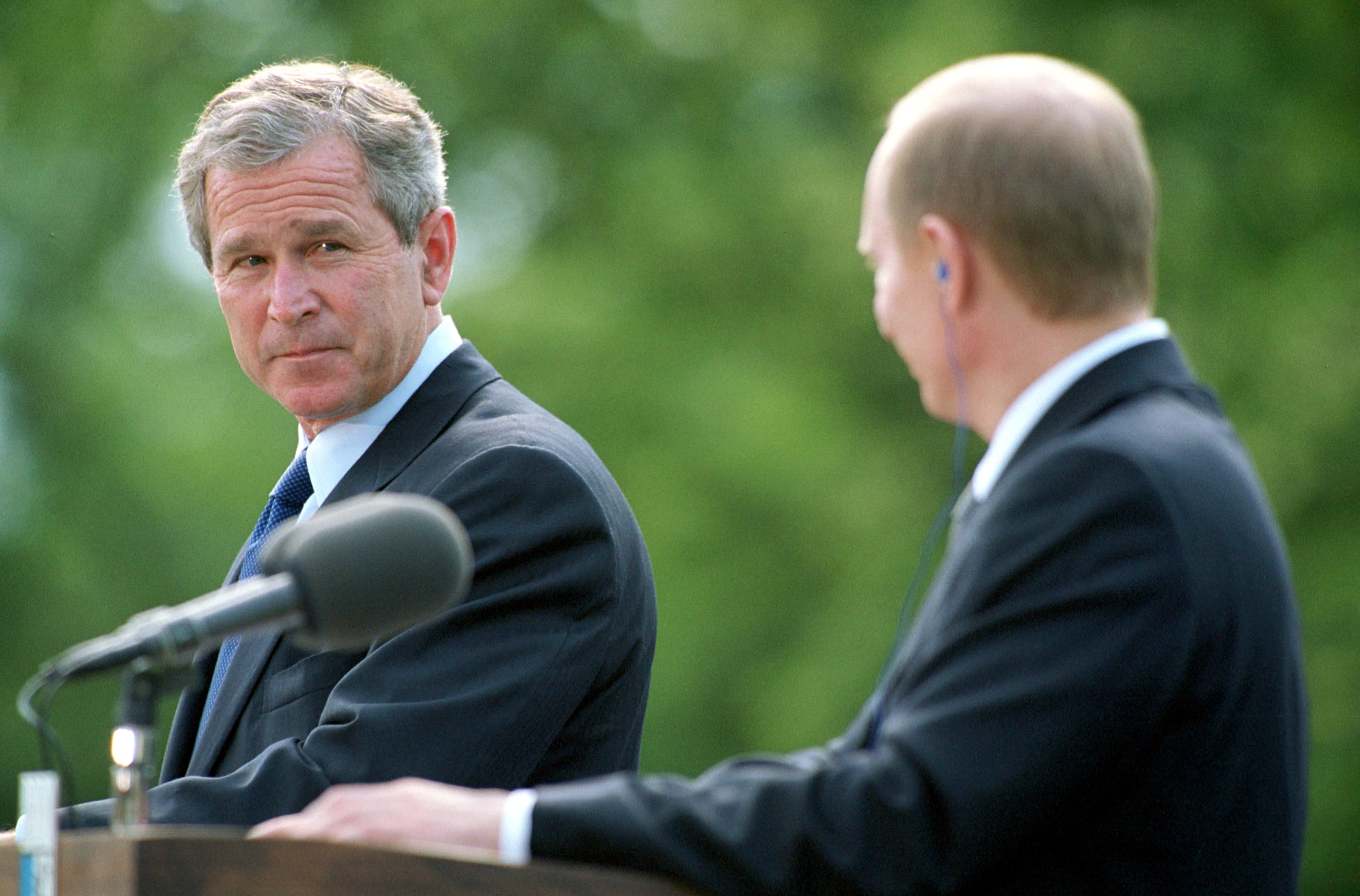

One moment that stands out to him is the summit meeting between the US and Russia in Slovenia, in June 2001 – just months before 9/11. At the closing press conference, in response to a question about whether he could trust Putin, Bush said. “I looked the man in the eye. I found him very straightforward and trustworthy – I was able to get a sense of his soul.”

Condoleezza Rice would later write that, as a result of Bush’s comments, “we were never able to escape the perception that the president had naïvely trusted Putin and then been betrayed” – but such remarks nonetheless captured the emerging amenability of the time.

Between 2001 to 2003 he was becoming more hubristic. On one of the visits, there were more horses, more luxury, more gold toilet fittings, and so on, in his dacha

This period of exploration with Putin “was not just a European thing or a Blair thing,” says Manning. “Rice, Bush and co were very interested in seeing whether some new kind of relationship could be built.”

Two months after the summit in Slovenia, the western world was shaken to its core: 9/11 was a moment that changed the course of history and marked a turning point in global relations. It was also one that briefly brought Russia and west closer together.

“We got a call from Putin on the day of 9/11,” says Powell. “He phoned up and asked what Russia should do. He offered intelligence sharing and help. Shortly after that, Tony went on a world trip to France and Germany, then to New York, DC, back to UK and then Moscow.

“Putin there was very amenable, very helpful, very friendly. He offered basing [for the invasion of Afghanistan]. He tried to encourage Tony to fly down to Tajikistan, which was were the Russians wanted US forces and UK forces to base themselves in attacking Afghanistan.

“During the trip, Putin invited Tony back to his dacha; he was very friendly. They played pool. They had a joint call with Bush. It was all very informal and normal.”

Nato, now the subject of Putin’s ire, was similarly drawing closer to the Russian regime. In October 2001, just weeks after 9/11, as Putin was meeting EU officials in Brussels, Robertson remembers being asked by the president: “‘When are you going to invite Russia to join Nato?’ I said, ‘Well, we don't ask countries to join Nato, they have to apply.’

“And he said, ‘We're not going to stand in line with all the other countries that don't matter.’ I told him, ‘Can we just stop the diplomatic sword dance, just build a relationship and see where it takes us.’

“He just stopped at that point. I don't think he was entirely serious in putting it forward. He knew the answer. But if you're a good politician, you never ask a question unless you already know the answer.”

Despite Putin’s machinations, it remained the case that Russia and Nato were slowly converging, as reflected in the establishment of the Nato-Russia Council in 2001. “The high point” of this relationship, as Manning puts it, came with the first meeting of the council in Rome, in May 2002.

“Almost at that point it felt that some kind of structural cooperation was going to be possible between the Nato heads of government and Russia in an entirely novel way,” says Manning.

But while the “rational Putin was definitely on top” for the first free years, says Powell, there were still low-level warning signs creeping into sight which pointed to what was to come.

“Between 2001 to 2003, what struck me was that he was becoming more hubristic. On one of the visits, there were more horses, more luxury, more gold toilet fittings, and so on, in his dacha. He was living this imperial lifestyle, rather than a normal leader-type lifestyle. And that got worse.”

Manning, too, was harbouring his own doubts of Putin and what the man’s true intentions were. “My sense of the man then was of somebody who was weary, who was feeling his way, who was instinctively suspicious, who would test propositions and people. There was a sense I think, even at the beginning, that relationships were more likely than not to be zero sum in his eyes.”

‘The great betrayal’

John Kampfner has met Putin on three occasions during his career as journalist, author and academic, but it is the encounter from 2004 which stands out in his mind. Kampfner was attending the first annual conference of the Valdai Club, held in Putin’s presidential residence on the outskirts of Moscow.

The meeting coincided with the Beslan school siege, in which 333 people, including 186 children, were killed after Chechen terrorists stormed a secondary school and held students and staff hostage. Russia was widely condemned for its handling of the attack and the excessive force it wielded, including tanks and thermobaric weapons, to bring the siege to an end.

He can be quite combative when people ask him questions and ask him deliberately provocative questions. He comes back like with like

Kampfner, entrusted with asking the first question, used the incident and wider Chechen war to “talk about Russia's borders and instability in the former Soviet countries”. The response he got remains seared into his memory to this very day.

“He answered me for 30 minutes – a 30-minute soliloquy in which I was sitting right opposite and he never once took his eyes off me,” says Kampfner. “There I was looking at him and then looking at my notebook and writing things down, looking back up again and his eyes hadn't moved. It was like a radar that's locked on you. It was quite an unnerving experience.

“He was getting impassioned but there was a coldness to him. It was basically a long cri de coeur of grievance about how he had tried to be friends with the west, he was the first to get in touch, after 9/11 to offer support to the Americans, which was true.

“He said he had given the Americans their bases to attack Afghanistan a couple of months after that, even though he had had misgivings. He had more than misgivings about Iraq, but he didn't stand in the way of the Americans on that. ‘And what have I got in return? All I've got is you, the west, fomenting trouble on my peripheries.’”

Putin believed he was being “incredibly pro-west and daring between 2000 and 2004,” says Kampfner - yet, at the same time, he had closed down the country’s only independent TV station, driven out various oligarchs and imprisoned Mikhail Khodorkovsky. “So he was clamping down domestically, but thought he was being amenable to the west yet felt he was getting nothing in return.”

Dejevsky was also present during that first Valdai conference, and has since attended the majority of annual meetings held by the group. She remembers Putin switching into a “crude and belligerent” register as soon as the topic of the Beslan massacre was raised.

“He was very quick into a sort of barrack-room language. That's a register that coexists alongside his formal register. It's a part of who Putin is, and it probably reflects some of his tough background as a kid, it probably reflects his time in the KGB and all that.

“He can be very he can be quite combative when people ask him questions and people ask him deliberately provocative questions. He comes back like with like.

“But at that first meeting, what was interesting was that he'd been in power maybe three years. He came into the room by himself with an interpreter but had no entourage, nobody was sort of accompanying him. That changed over time, but he’s never deferred to anybody during these meetings. He’s not looking over his shoulders. He’s very well briefed and knows all the facts.”

Fractures in the relationship between Russia and the UK were also beginning to appear during this period. Putin had by no means stepped back, but by the middle of 2004, the two countries were no longer on steady footing.

The falling out over Akhmed Zakayev was a case in point. Deputy prime minister of Chechnya at the time, Zakayev was charged with 13 offences by Russia, including acts of terrorism, torture and the kidnapping of two Orthodox priests. Zakayev had fled Russia and taken refuge in the UK, which, following the intervention of a British court in November 2003, rejected Putin’s calls to extradite the wanted Chechen leader.

“Putin was personally furious at this,” says Lyne. “Putin, who doesn't understand the west, has spent very little time in the west and doesn't understand the rule of law. He simply could not understand these were not political decisions. So I kept being told that Putin was puzzled by this ‘Why has Tony Blair taken the political decision not to send Zakayev back to Russia?’

“We explained to we were blue in the face that we had courts in Britain, the prime minister could not overrule the courts even if you wanted to. Putin took this very personally. Blair had done something bad to him. Therefore, he had to retaliate because that's absolutely in his character. It's the little boy who used to get into fights in the backstreets of Leningrad and learn to knock other boys over, or, as he once said, ‘Get your retaliation in first.’”

The retaliation came in the form of attacks against the British Council in Russia, which was helping to teach English to local citizens and promote education. Thugs in leather jackets, “ordered by Putin,” says Lyne, began bursting into British Council offices in Moscow and removing computers, destroying files and intimidating staff.

“That was characteristic of the Putin of that period,” says Lyne. “And that was the sort of little guy, who's very insecure and who thinks that somebody is putting one over him so he's got to get his own back.

“In 2003, one sort of felt that Putin was swinging. And I do remember that this led to a fair amount of sort of private debate in places like Downing Street, in the White House, as to whether the guy was going off in a different direction.”

Those flashes of emotion which intermittently stripped back the thin veneer of civility he struggled to maintain were becoming more conspicuous, more forceful, more telling

The war in Iraq was another sore point for Putin, who “felt he was not being allowed on the top table or shown the respect that Russia deserved,” says Powell. The west itself was starting to divide and to “split into different camps” over the conflict, making it perhaps “irresistible for the Russians not to play one end off against the other side,” adds Manning.

Fast forward to September 2004, as Kampfner and his fellow Russian specialists emerged at 1am from Putin’s lavish mansion in Novo-Ogaryevo, there was a clear consensus among the group that “Putin had given up on the west”.

“No matter what viewpoint we had, we all sort of agreed that that was the period in which Putin turned,” says Kampfer. “He had basically reverted to Soviet type, having sort of flirted with what he thought was a risky position of being moderately friendly to the west. He then basically went back into his adversarial mindset, on the basis of what he insisted to himself was a great betrayal.”

‘You don't care about us killing dissidents on your streets’

Powell’s final encounter with Putin came in June 2007, at a G8 summit held by Angela Merkel in the north German resort of Heiligendamm.

Relations with Putin were rapidly deteriorating. Months earlier, in February, Putin had delivered his infamous anti-American speech at the Munich Security Conference, where he condemned the US for its “almost uncontained hyper use of force in international relations”.

Before that, in November 2006, Alexander Litvinenko, a former KGB agent and prominent Putin critic, had died after being poisoned with polonium-210. Two Russian spies were implicated, and it was later concluded that Putin himself had given the order to assassinate Litvinenko.

After years of appeasement and pleasantries, Blair, accompanied by Powell, arrived in Heiligendamm with the aim of “telling Putin what he really thought”.

“So it was Putin, a Russian interpreter, Tony and me,” remembers Powell. “Tony was very forthright and saying what he thought about killing Litvinenko in British streets using nuclear material, what he thought about the autocracy.

“Putin just came back with two barrels. ‘You don't care about us killing dissidents on your streets. Your democracy is terrible, look how corrupt you are.’ It was a very, very abrasive and rough conversation.”

Although not as confrontational in tone, a meeting between Gordon Brown and Putin in June 2008 proved similarly frosty. Tony Brenton, who was the British ambassador to Russia from 2004 to 2008, witnessed the exchange take place in Moscow, where G8 finance ministers were meeting at the time.

“They were very well informed on what's going on in politics in other countries around them,” says Brenton. “It was becoming clear that Gordon Brown was going to inherit the prime ministership from Blair, so they got him in to meet with Putin at the summit.

“It was a very interesting encounter because, at that time, paralleling today, in some ways, gas prices had just gone through the roof. We felt that the Russians were responsible for this in some sense, and so Brown went in to persuade Putin that they should release more gas onto the market.

“Putin was quite struck by this. He knows the details of the gas market backwards. His response to Brown was, ‘well, the reason the UK is being hit by gas prices is because you buy all your gas on the spot market, and that's why it’s expensive. If you went over to long-term contracts with Gazprom, it will be much cheaper for you.’

“He knew his brief backwards. The only politician who I've dealt with who has better mastered the material put to them was actually Margaret Thatcher.

“Brown sort of fended it all off in a very diplomatic way, but he lost the encounter, he lost the discussion because Putin's point was perfectly credible.”

It was a very different Putin to the man who had first rubbed shoulders with Blair all those years ago in St Petersburg. The tentative, unassuming and deferential qualities had long since dissipated, replaced by a constant streak of confidence and ruthlessness which was serving to widen the yawning divide between Russia and the west.

The darker side to Putin was beginning to prevail, suppressing the pragmatism of his earlier days in office. Those flashes of emotion which intermittently stripped back the thin veneer of civility he struggled to maintain were becoming more conspicuous, more forceful, more telling.

Lyne’s last meeting with Putin was at the 2008 Valdai meeting – just one month after the Russo-Georgian war. During the conference, one brave British journalist asked about the Litvinenko affair, drawing a “really sharp and rebarbative answer” that reflected Putin’s self-assurance and growing sense on invincibility, says Lyne.

Most are in agreement that there is a quiet but flammable rage lurking beneath the surface – visceral and violent enough to sporadically shatter the controlled persona

“I forget the exact words but essentially he didn't take the opportunity to go through any sort of crocodile tears of regret about the death. He shot back in words that effectively said, ‘He got what he deserved’. That was the hard side of him coming out that he couldn't restrain.”

James Sherr, a senior fellow at the Estonian foreign policy institute, was another to observe Putin’s metamorphosis from reluctant pragmatist to dictator, having attended numerous Valdai meetings as a Russian academic between 2008 and 2017.

At the 2009 conference, Sherr recalls, Putin “very casually” declared that there was “absolutely nothing wrong with Adolf Hitler's foreign policy or anything he did until March 1939,” when the Nazis annexed the Czech parts of Bohemia and Moravia.

“Hitler’s argument was that he was simply re-unifying historical German lands,” says Sherr. “In the same way, Putin was now speaking about the unity of Russia and the Russian world.

“It was becoming clear that the doctrinal basis for Putin's foreign policy was very similar to that earlier period of Hitler's policy, where he said to Chamberlain and others, ‘I'm just taking what is ours historically.’

“This rationale of Putin’s has been around for a long time.”

By the mid-2010s, direct Western contact with Putin had become a rarity. After the annexation of Crimea, there was little desire to recapture the spirit of exploration shared between Russia and the West in the first half of the previous decade. Some western counties, leaders and organisations kept closer to Putin than others, but the zeitgeist of the time was generally fractious and distant.

Angela Stent, a foreign policy expert who has attended the majority of Valdai meetings since 2004, saw this mirrored in the conferences that were held from 2014 onward.

The meetings had swollen in size, losing the intimacy of the earlier meetings and making it harder to hold direct one-to-one conversations with Putin, who was becoming ever isolated within his inner circle. Increasingly, they were becoming a celebration of Russia, the country’s “own version of Davos”, says Stent.

“In the last eight years, Putin has started using the conferences to inveigh against LGBTQ rights, against political correctness, against what he saw as the decadence of the European Union, ‘We are the true Christians, the West is Satanic.’

“I think that came together with this greater sense of triumphalism. ‘We've taken back Crimea and our people are patriotic about this,’ while greatly criticising the Western sanctions but saying that their economy had the means to thrive.

“In one year, they brought out this patriotic hero cheesemaker and said we can make our own Parmesan cheese and mascarpone. It was getting shriller and shriller, more anti-Western and more anti-American. Although we no longer had that face time with Putin, it was reflective of where his head was at.”

Such insights open a window, as small as it may be, into the mind behind the man that is Vladimir Putin. Kept distant and isolated from the glare of Western observers, the Russian strongman remains an enigma, his motives in Ukraine muddled and unclear, but the perceptions built up by those who have spent time in his company share some commonalities.

Most are in agreement that there is always a quiet but flammable rage lurking beneath the surface – visceral and violent enough to sporadically shatter the controlled persona he has cultivated over the years.

It’s this rage which has driven Putin to acts of savage barbarism and the establishment of a totalitarian regime that shows little mercy to its enemies, they say. It’s a rage that has been expressed throughout his administration, in the killing of civilians in Chechnya, the flattening of Grozny, the brutal mishandling of the Beslan school siege, the bombing of Aleppo, the poisoning of dissidents, and the rape, torture and murder of innocent Ukrainians.

Most are also in agreement that they never thought Putin capable of the horrors being wrought in Ukraine today. True, they were always aware of the “two Mr Putins” that co-existed, of the impassioned volatility and combustibility that shaped his world views and actions, but none believed the monster within would come to dominate in the way it has.

In that sense, they are all in agreement that power has proved the ultimate corrupting force, pushing Putin to a state of mind in which his inherent capacity for pure evil has been unleashed and allowed to reach its full potential.

“He’s been there far too long, remote from ordinary people, from challenge, from any real set of political constraints,” says Robertson. “And it’s allowed a lot of the emotional flashes that I saw to become major obsessions and brought us to where we are today.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments