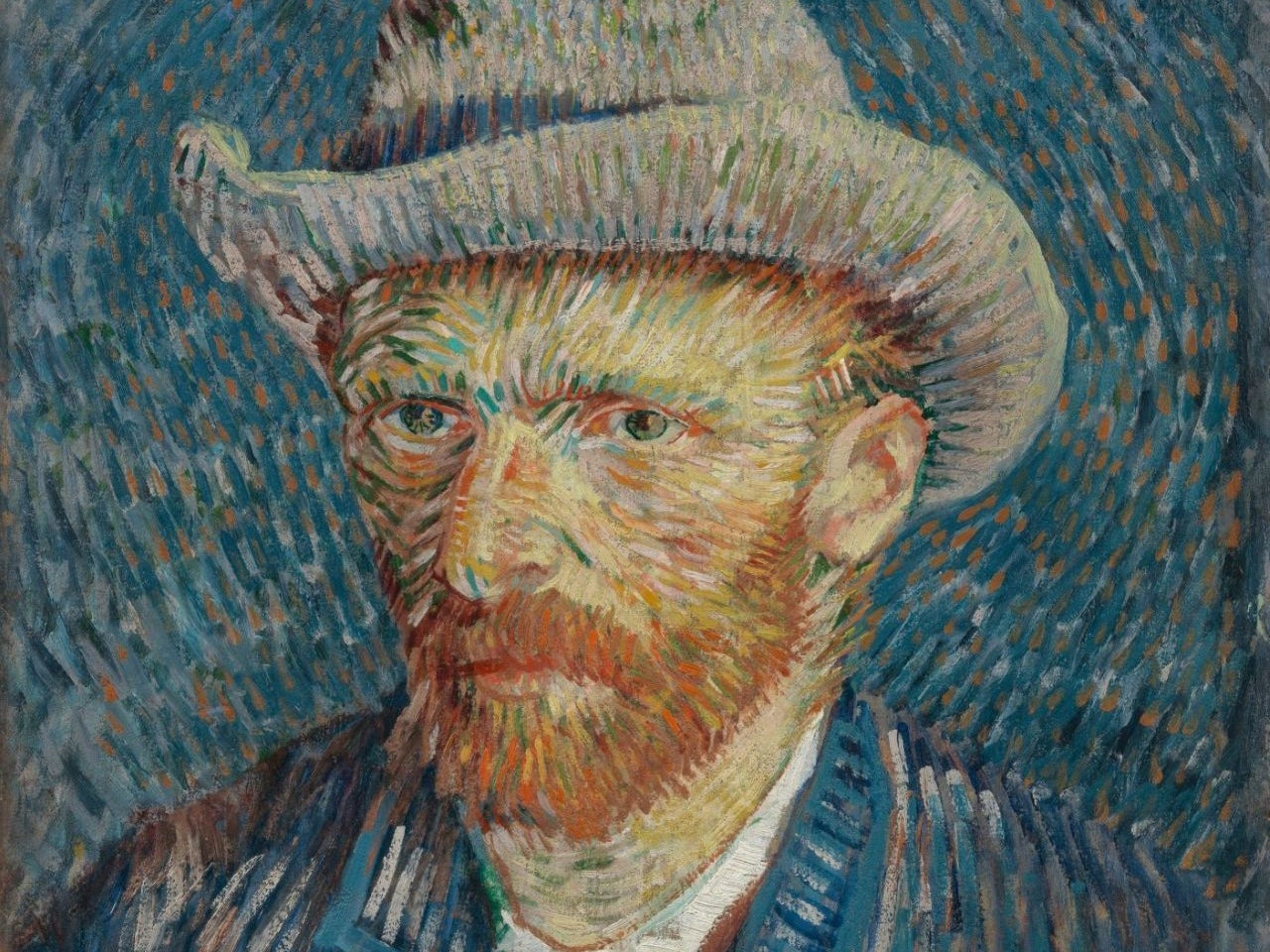

Montmartre put the colour in Van Gogh’s life and art

When he arrived in Paris in 1886 Vincent van Gogh was just another wannabe. When he left in 1888 he was ready to change the world. William Cook reports

I’m standing on a busy boulevard in Montmartre, staring up at a third-floor apartment that changed the course of modern art. This apartment block doesn’t look like much. Indeed, it looks much the same as countless other apartment blocks all over Paris. However, its significance in art history is immense, for it was here that Van Gogh became a great artist.

When Vincent van Gogh arrived in Paris, in February 1886, he had less than five years left to live, yet he still only had a handful of notable paintings to his name. He’d been trying to make it as an artist since 1880, but he hadn’t sold a single picture. Yet during the two years he spent here, everything came together – the difference is plain to see. By the time he left Paris, in February 1888, he was painting masterpiece after masterpiece. So what took place in Paris during those two years? What happened here in Montmartre that transformed this anonymous oddball into an artistic genius?

Vincent was in his late twenties when he decided to become an artist, already rather old to be starting from scratch. When he arrived in Paris, shortly before his 33rd birthday, he’d been painting obsessively for six years, yet he had precious little to show for it. His paintings were powerful, but his style was clumsy and his subject matter was unremittingly austere.

Most of his pictures depicted shabby peasants, toiling away against a bleak backdrop of muddy fields and stormy skies – hardly the sort of thing you’d want to hang above your mantelpiece. Many of these pictures, like The Potato Eaters, are now acknowledged masterpieces, but no one thought so at the time. They looked so dour and gloomy, no wonder they didn’t sell.

The only reason Vincent could carry on painting these unsellable pictures was because his younger brother Theo paid him a modest monthly stipend, leaving him free to paint full time. Theo never doubted Vincent’s talent, or his dedication, but he doubted whether his elder brother would ever make a living as an artist. Theo knew what he was talking about. He worked in the Paris office of the prestigious art dealers, Goupil – the firm Vincent had worked for, briefly and unsuccessfully, 10 years before.

Unlike Vincent, Theo was a proficient art dealer. His personal tastes were progressive, but he also understood what sold - and the fact that he had no illusions about Vincent’s commercial potential (or rather, the lack of it) made his tireless generosity even more remarkable. Theo was not a wealthy man (he had a steady job at Goupil, but he was merely a salaried employee) yet he supported Vincent throughout his artistic career. Throughout those ten years, that monthly stipend was Vincent’s only source of income.

Vincent and Theo were very close, but for most of that momentous decade they saw each other relatively rarely. Vincent was living in Belgium and the Netherlands, and latterly in the French countryside. Theo was living in Paris, so their relationship was mainly conducted by mail. Theo would write to Vincent and enclose some money. Vincent would write back, but his letters weren’t just thank you notes. He wrote regularly, prolifically – he opened up his heart. Sadly, few of Theo’s letters survive, but Theo kept hundreds of Vincent’s letters, which add up to a kind of autobiography – a uniquely intimate account of an artist on the brink of greatness.

Vincent’s letters were full of heartfelt pleas, saying how much he missed Theo and how he longed to see him, but although these sentiments were sincere, this long-distance relationship suited both men rather well. Even at the best of times, Vincent was demanding, exhausting company, fluctuating wildly between manic enthusiasm and abject despair. His correspondence was no less intense, but in his letters Theo saw the best of him. Here, his intensity was controlled and channelled, as it would be, eventually, in his painting. That all changed when Vincent came to Paris. It was the best two years of Vincent’s life, and the worst two years of Theo’s.

The first Theo heard of it was in January 1886, when Vincent wrote to him from Antwerp, saying he planned to come to Paris and rent a garret, where he would live and work. However, Theo knew Vincent far too well to simply take him at his word. He wrote back and suggested that Vincent put off his arrival until June, to give him and his wife Johanna time to find a bigger flat. He knew if Vincent came to Paris, they’d have to put him up.

Theo was quite right, of course. A month later, without warning, he received a short note saying that Vincent was waiting for him at the Louvre. Sure enough, Vincent had nowhere to stay (he’d left his lodgings in Antwerp in a hurry, leaving behind most of his belongings, including several of his paintings, which were never seen again).

For the first time, Vincent was now part of a community, something he’d been searching for throughout his lonely adult life

A tougher man than Theo would have told him to get lost. Fortunately for Vincent, Theo had the patience of a saint. He took Vincent back to his compact apartment in Montmartre, and then set about finding somewhere big enough to accommodate his brother, as well as his wife. As Johanna remarked: “The old love and friendship which bound them together since childhood did not fail them even now.” A few weeks later, the three of them moved into the apartment I’m standing outside today.

Living with Theo and Johanna did Vincent the world of good. “You would not recognise him – he is in much better spirits than before,” wrote Theo, to their mother, back in the Netherlands. “He makes great progress with his work and has begun to have some success.” The progress was clear to see, but the success was fairly finite: a few exhibitions in local bars and cafes, which garnered praise from other painters but no sales. Nevertheless, compared with his previous work, which had been greeted with indifference or incomprehension, this was a step in the right direction. Theo told their mother: “I think the most difficult period is passed.”

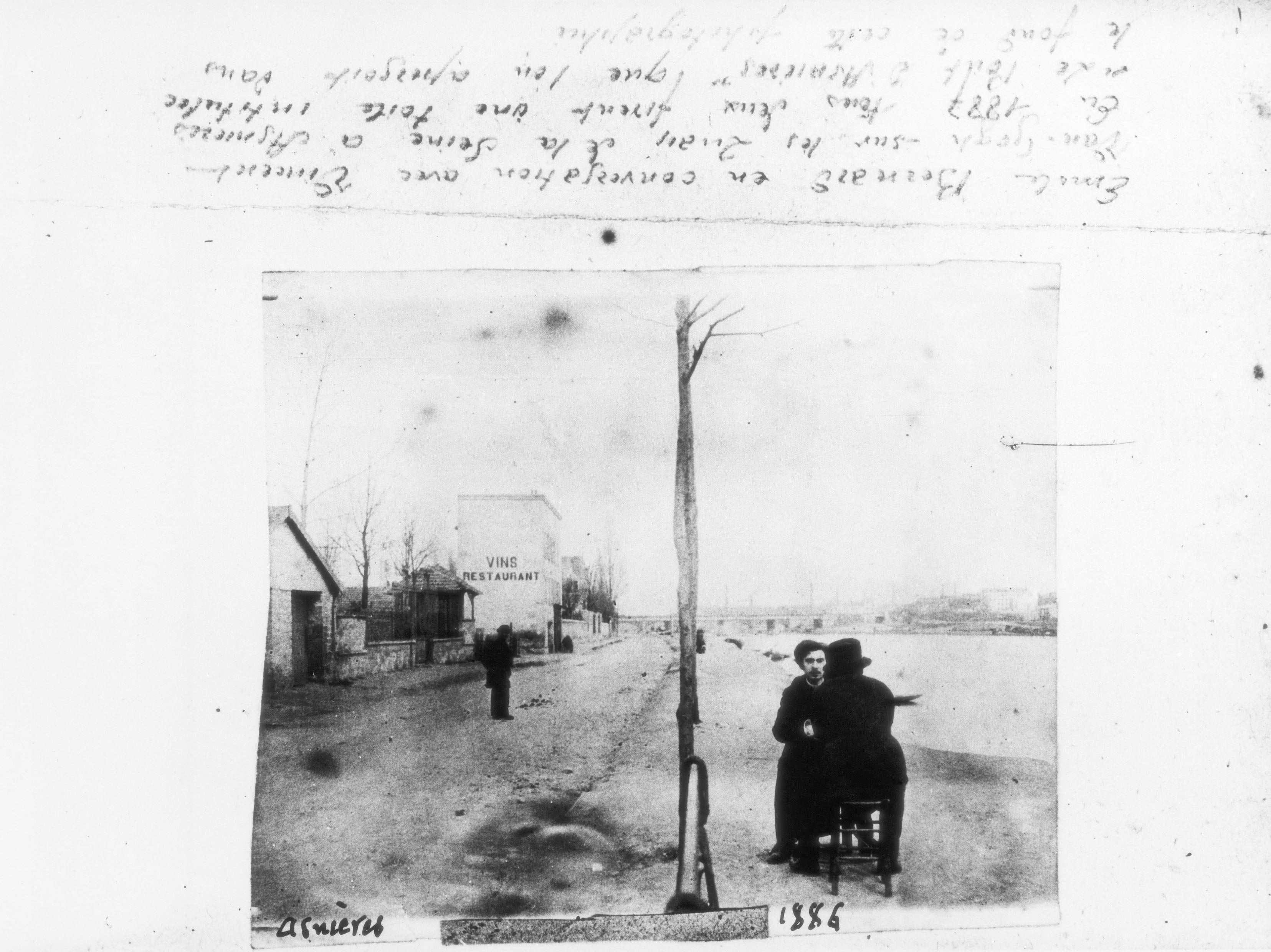

For the first time, Vincent was now part of a community, something he’d been searching for throughout his lonely adult life. Here in Montmartre, he encountered a group of like-minded artists who shared his interests and were fairly forgiving of his eccentricities. Toulouse-Lautrec became a close friend. He also befriended Paul Signac and Georges Seurat, whose Pointillist paintings had a significant impact on his emerging style.

The biggest influence on Vincent’s painting was his close encounter with the Impressionists, those groundbreaking French painters who focused on the effect of light, a radical departure from realism which laid the foundation for modern art. Theo was an early champion of these innovative artists, and gave them wall space at Goupil, the gallery where he worked.

For Vincent, this was a revelation. “In Antwerp, I did not even know who the Impressionists were,” he confessed (studying paintings by Delacroix and Millet in the Louvre was more his style). Suitably impressed, he painted several pictures in an Impressionist manner, and though he eventually moved away from this form of painting, considering it somewhat superficial, it was an important stage in his development, which informed his own aesthetic. The Impressionists returned the compliment. Their admiration for his work spurred him on and gave his confidence a welcome boost.

“When he came to Paris from Antwerp, he was searching for the real avant-garde,” says Edwin Becker, head of exhibitions at the Van Gogh Museum, when I catch up with him in Montmartre, on a walking tour of Van Gogh’s Paris. “He hadn’t grasped the essence of those modern painters.” Coming to Paris and moving in with Theo really brought him up to speed. Living here, he felt emboldened to experiment with all sorts of different techniques. “He’s almost like a sponge, absorbing all the influences he’s seen.”

“He really learnt to appreciate the Impressionists – he was painting in a very dark palette before,” says Mariska Hammerstein, the creator of this walking tour. “Here, he learnt something different – he really changed his colours and his style of painting.” The explosion of colour in Vincent’s later paintings is usually attributed to his subsequent exodus to the sunny south of France, but in fact it started here, in Paris. The climate here was no better than it was in his native Netherlands. It was his vision which had changed.

Paris was also the place where Vincent’s interest in Japanese art blossomed: he’d picked up a few Japanese prints in Antwerp, but Paris was full of them. He dated one of Degas’ models. He had his portrait painted by Pissarro. It was here that he befriended Paul Gaugin, who inspired his iconic Sunflower paintings, and prompted his pilgrimage to Arles, where he painted his greatest works. “Everything which he does later already has its roots here in Paris,” says Becker. “He was constantly going to exhibitions.”

However, Vincent’s greatest stimulus was Montmartre itself. Perched on a hill high above the rest of Paris, Montmartre is still a place apart, a virtual village within the city, and back then it was even more so. It was outside the city limits, with wide open countryside beyond. Then as now, it was also a place where people came to drink and dance and let their hair down. For Vincent, it was this contrast between rural and urban life which was so invigorating. He drew the street life and the night life, he painted the allotments and the market gardens. It was a creative enclave and a red-light district – all of human life was here.

Vincent couldn’t have stayed in Paris any longer. He was driving Theo and Johanna crazy, and the stimulation of Montmartre threw his fragile psyche into overdrive

Vincent had no trouble making friends, but he had a lot of trouble keeping them. After a short while, his volatile personality began to grate. “Of all the things that Theo did for his brother, perhaps nothing proved a greater sacrifice than living with him for two years,” declared Johanna. “When the first excitement of all the attractions of Paris had passed, Vincent fell back into his old irritability – that winter his temper was worse than ever, and it made life very hard for Theo.”

Vincent refused to let him rest. When Theo arrived home at night, exhausted after a hard day at the office, Vincent would insist on engaging him in fierce debates about art. “My home life is almost unbearable – no one wants to come and see me anymore because it always ends in quarrels,” confided Theo, in an anguished letter to their sister. “I wish he would go and live by himself. He sometimes mentions it but if I were to tell him to go away, it would just give him a reason to stay.”

Vincent was fundamentally goodhearted, but he had no filter. He was outspoken and argumentative, incapable of compromise, and his sudden, violent mood swings made him hell to live with. “It seems as if he were two people – one marvellously gifted, tender and refined, the other egotistical and hard-hearted,” concluded Theo. “I have often asked myself if I have been wrong to help him continually. I have often been on the point of leaving him to his own devices.” Yet despite countless provocations, he never did.

When Vincent left Paris in February 1888, Theo was relieved to see him go, but his relief was tinged with sadness. “It still seems strange that he is gone,” he reflected. “He was so much to me.” Vincent travelled south, to Arles, where he painted the priceless pictures that Theo always knew he had in him. He cut off one of his ears with a cut-throat razor and spent some time in an insane asylum. Less than three years later he was dead, killed by a bullet through the chest. Suicide was the official verdict. He took a long time to die. The doctor could do nothing for him. He was 37 years old.

Theo outlived Vincent by only six months. He died aged 33, from the side-effects of syphilis. He left a year-old son, Vincent Willem, named after his beloved elder brother. Over the 10 years that he’d supported him, Theo had accumulated a vast collection of Vincent’s unsold paintings. He left them to Johanna, and when she died, in 1925, she left them to Vincent Willem. In 1973, Vincent Willem gave the bulk of this collection to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, the biggest Van Gogh collection in the world.

Vincent Van Gogh has become a national icon in the Netherlands, but French art-lovers regard him as one of their own, and you can see their point of view. Vincent was born and raised in the Netherlands, but almost all of his great paintings were painted here in France – in Paris, then in Arles and finally in Auvers. His defining inspiration was the French countryside, and French artists like Millet and Delacroix. “He’s a Dutch painter,” says Becker, “but if he hadn’t gone to Paris, he wouldn’t be the painter he is.”

It’s here in Montmartre that his ghost lives on, not only in the old landmarks, but above all in the creative culture of the place. Montmartre is no longer cheap (in fact nowadays it’s pretty pricey) and as Paris has grown it’s drifted from the edge of town towards the city centre. But the old joie de vivre is still there, the feeling you could come here and fall in love or form a band or write a novel. You probably won’t do any of these things, but if you were going to do just one of them, you feel you might do it here.

Vincent couldn’t have stayed in Paris any longer. He was driving Theo and Johanna crazy, and the stimulation of Montmartre threw his fragile psyche into overdrive. He had to get away, if only to preserve his sanity for a little longer, but the time he spent here was crucial, the final chapter in his long apprenticeship. As his nephew Vincent Willem van Gogh observed: “Having found his own way, his paintings at the end of his stay in Paris are almost as full of colour and expression as the famous ones done in the South.”

When he arrived in Paris, in 1886, Vincent van Gogh was just another wannabe. When he left, in 1888, he was ready to change the world.

The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam (www.vangoghmuseum.nl) houses the world’s largest Van Gogh collection. The Museé d’Orsay (www.musee-orsay.fr) in Paris boasts one of the best Van Gogh collections outside the Netherlands. For more information about Vincent Van Gogh in Montmartre, visit www.dutchheritageworldtours.nl

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments