Rediscovering our cities: warts and all stories of invisible city dwellers

After a year of empty streets, life is slowly returning to our cities. James Moore on a new film series at the Barbican, which explores the grimy underbelly of our urban existence

I was driving from LA though the desert. You come up to the top of a hill and you look out into black desert and there in front of you are the glittering lights of Vegas. I thought, this is such an incredible metaphor. This glittering, profit-eating, capitalist centre in the middle of the desert, this alienated elegance. Then I started walking around and I found it was nothing like that vision at all. There were all these horrible buffets with bad food at $4.99 for all you can eat. It was tacky. That’s what I thought was so interesting.”

So says Nina Menkes, the maker of the remarkable Queen of Diamonds, a film which offers a unique vision of the city of sin. Astonishingly made for just $65,000, at least half of which covered the cost of the 35mm film, it is one of the centrepieces of the Barbican’s Return to the City season. The event is well timed as some of the west’s Covid-wracked cities start to emerge blinking into vaccinated sunlight. Commerce and culture, largely on life support, have started to move again. The streets are no longer deserted. But they're changing. The gleaming glass and concrete towers that people commuted into daily have been hollowed out with remote working taking over for millions of employees.

Much of a city’s allure is lost if only bankers and businessmen can live there. Perhaps the office space they are vacating could be converted into affordable housing

One in 10 UK restaurants have closed. More will follow, particularly the sandwich shops and cafes, which relied on commuters for their custom. The most recent figures from property website Zoopla say rental values in London have fallen by nearly 10 per cent. Smaller, but still significant falls, were recorded in Edinburgh, Manchester and Leeds. New York has experienced something similar.

That may be a positive development at least if it’s sustained; especially if the flight from urban centres encouraged by remote working helps facilitate the return of people previously priced out. Much of a city’s allure is lost if only bankers and businessmen can live there. Perhaps the office space they are vacating could be converted into affordable housing. New York is looking at it.

On the other hand, the lifting of eviction moratoria is poised to deliver a savage blow to people who are already struggling. “Things must change,” is a cry regularly heard in the wake of the pandemic. But will it be heeded. That’s the backdrop against which the Barbican’s season kicks off.

“We’ve been looking to do it for a while and this seemed like the right moment,” the event’s curator Alex Davidson tells me. “We’ve all been denied access to city spaces. It’s been eerily haunting and surreal to walk around them. It’s unnerving and disquieting for those of us that love being here because we thrive on the community, the diversity, the bustle and buzz of being around people.”

Davidson wasn’t short of options when he was compiling his selections. The world’s great cities are regularly at the top of casting directors’ lists. New York, Paris, Vegas, and LA are often leading characters in their own right, even if, say, Vancouver is frequently called upon to sub in and play their non-specific urban spaces (for tax purposes, you see).

However, he deliberately chose not to take the easy route. “Return to the City doesn’t offer an easy celebration,” he tells me. “It offers a warts and all view that invites us to consider what we want from these spaces in the future, how we might do things differently. We wanted to avoid the picture-postcard Hollywood films such as Roman Holiday,” he says, referring to the classic romantic comedy that netted three Oscars, including a best actress nod for Audrey Hepburn, who starred alongside Gregory Peck.

“I’m in no way criticising that film. It’s great. The stars are fantastic in it but we wanted to focus on the stories that aren’t told. Those of women, people of colour, working-class people. We wanted those stories to be given an airing.”

Menkes’ vision of Vegas fits into that. The city’s cinematic myth is absent. There are no mobsters, no high rollers, no MIT-trained card counters, no hustlers, no showgirls. There’s no glamour, no grandiose tragedy. Instead, Queen gives us a view of one of the workers without the rivers of money that flow into the corporate pockets of giant entertainment corporations and billionaires.

“I wanted to base the film on the people who work behind the table. They live on their tips. It’s low paid. Minimum wage. I was aware of the way Vegas was portrayed. I knew that it always focused on the gamblers and the babes, and I was like, what about the people who work there. What about the people behind the table?”

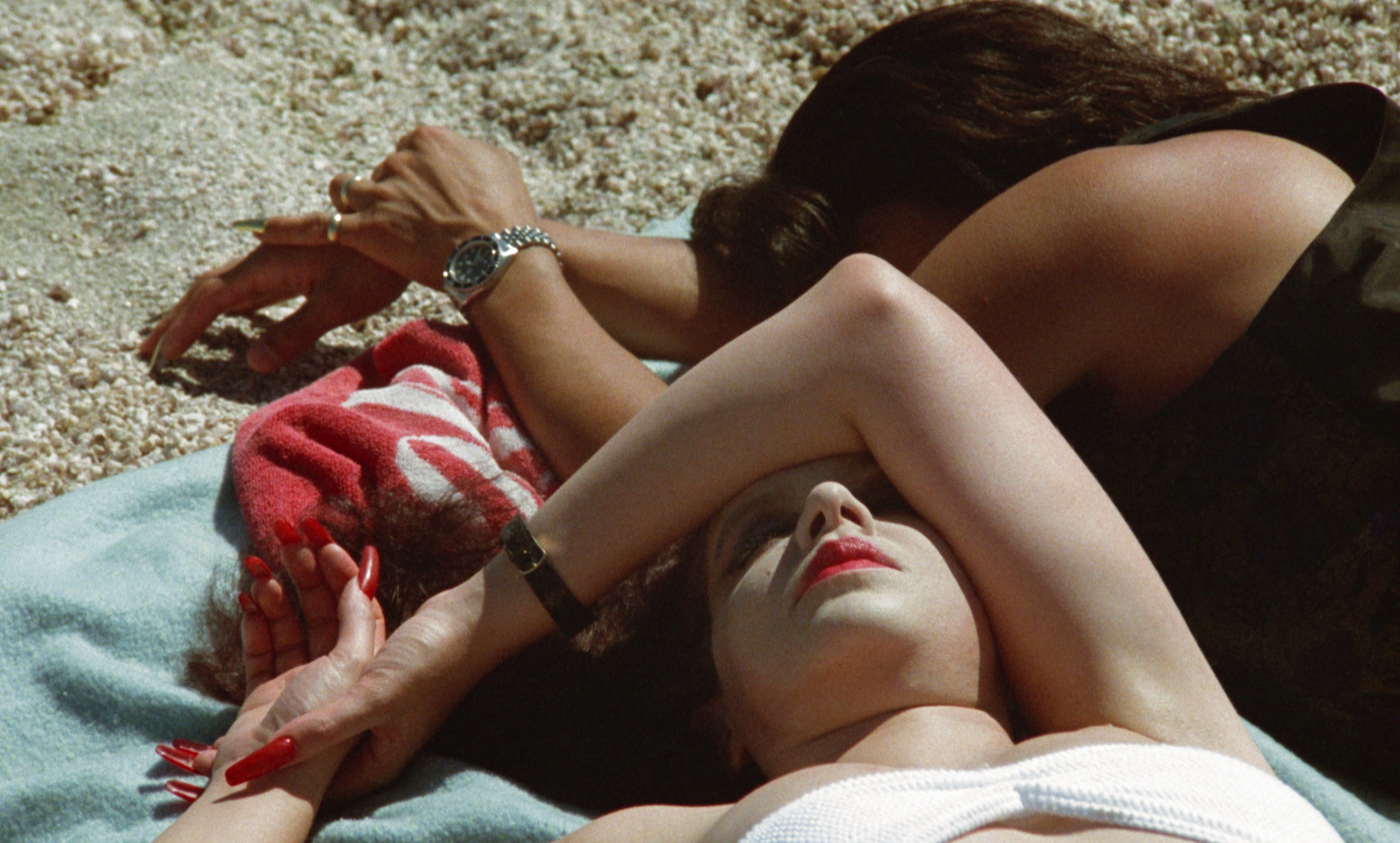

Tinka Menkes, her sister cast in the lead role, represents them. She lives in a cheap apartment with paper thin walls that do nothing to shield her from the sound of the guy down the hall beating his fiancee. The streets away from the famous strip are dusty and sandblasted, anonymous, uncomfortable, even vaguely threatening.

The most striking part of the film shows her at work, dealing cards for 17 and a half minutes, against a backdrop of flashing lights with a soundtrack of the bleeps and hoots of one-armed bandits and the ticking of a clock added later (clocks aren’t allowed on the casino floor). It shouldn’t work. And yet it does. It’s hypnotic. It draws in the viewer and disorients in the same way Vegas casinos disorient; they’re set up to snatch the patron’s sense of time and place with the aim of keeping them gambling.

There are different groups of players at the table, it cycles between five different takes, but at the centre is Tinka, utterly detached from the action around her, dealing hands in whose outcome she has no interest.

We tried to capture the alternative music scene, the freedom. If I see our film, I get the sensation of something nostalgic. We want life to go back to what it was before, to normality

“It was Tinka that persuaded me to put it together like that,” says Menkes. “I wanted to make her the centre of the film but at the same time express that she’s background. She’s in the centre of her own consciousness but she’s on the edge of what’s going on.

“All my friends said they’ll never let you shoot. You’ll have to create a casino. But I went up there and pitched the idea that I would make a film to commemorate Bob Stupak’s Vegas World, which is no longer there, and he gave me two weeks for free. We had a sign up saying anyone who wanted to play agreed to be filmed and no one noticed, even though we had this huge dolly.

“At one point I was thinking, where's my gaffer, and there she was on the slot machine pulling the arm. I had to drag her off it.”

Vegas, baby.

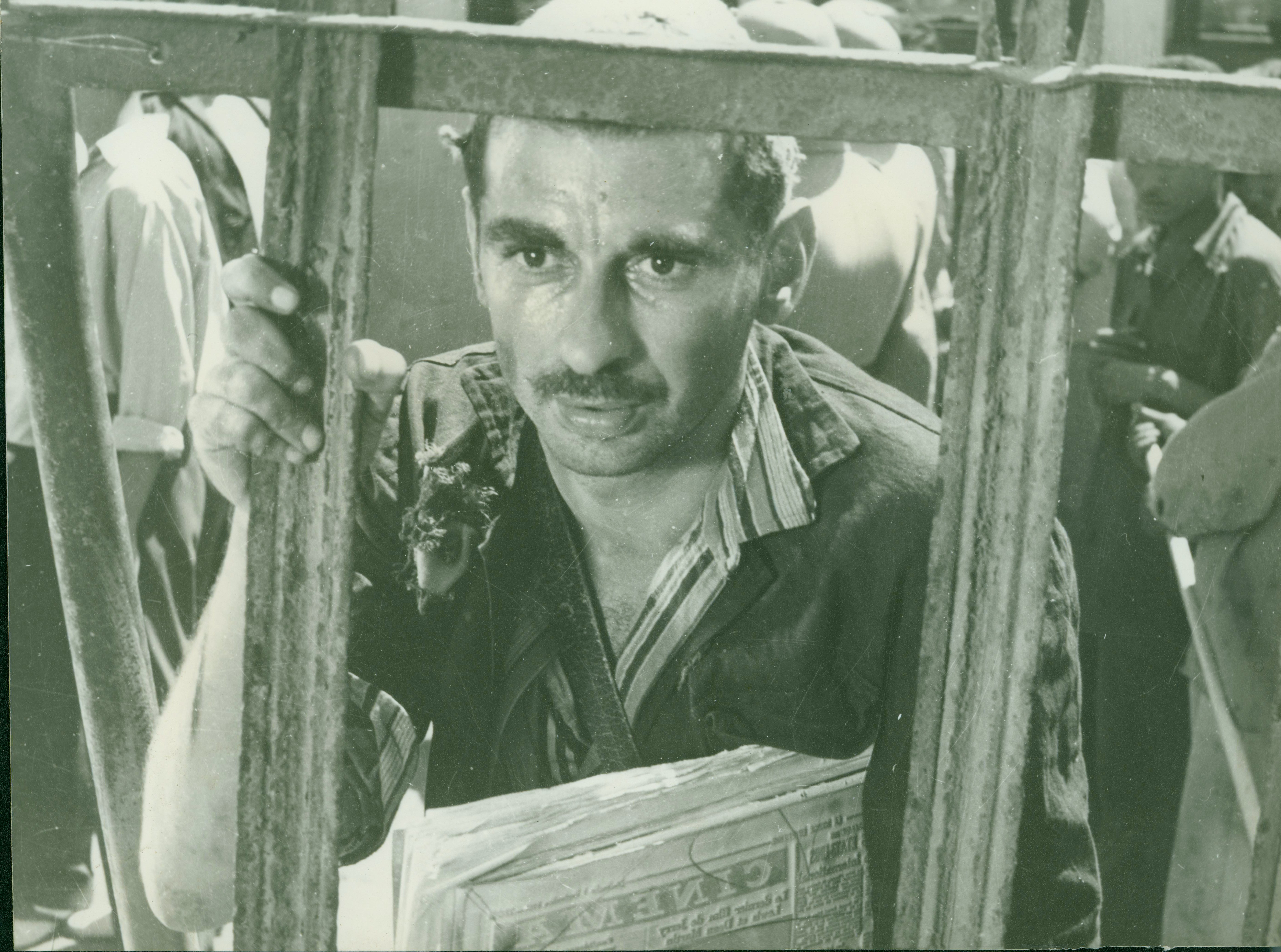

Another warts and all story of the unseen lives of a city’s workers featured in the season is the remarkable Cairo Station, which combines social realism with elements of film noir in its tale of Qinawi, a newspaper seller shunned because of his limp, and the obsession he develops for Hannuma. She is the beautiful and vivacious soft-drink seller, hopping on and off trains with her bucket full of bottles, engaged to be married to the porter Abu Siri, who is seeking to unionise his co-workers.

The film encompasses themes of sexual repression, gender-based violence and misogyny, the struggles of the urban working class, even ableism, a subject only seldom tackled and only rarely handled well when it is.

The film is all the more remarkable considering where and when – Egypt 1958, a few years before the film industry was nationalised – it was made. Many of its themes are just as relevant today as they were when it was made and it’s fascinating to consider how a remake might work, even though you can almost hear the critics murmuring “sacrilege”.

“A microcosm of the city in a small space,” says Davidson, who passionately believes the film deserves an audience beyond the limited number of cinephiles and academics who have seen it.

“Cairo Station really exposes the western bias of the best 100 film polls. For me, this is a masterpiece. It’s very simple. It’s quite short. It has everything in it. It exposes class issues, gender issues, disability. It’s such an easy film to understand. There’s so much complexity while being something anyone could enjoy.”

It is, even although its subtitling isn’t, all that it might be.

The working people who keep cities moving are often immigrants, and their plight is the subject of Nationalité: Immigré, a 1970s piece focussing on Paris and the cold welcome facing immigrants consigned to the harsh life in its banlieues, away from the city’s picture postcard interior. The struggles of their residents and the simmering tensions with police have famously been chronicled in La Haine and more recently Ladj Ly’s Les Misérables (don’t be fooled, it’s not the musical)

Nationalité: Immigré is different. It depicts the difficulties faced by someone just arrived to find work and money and accommodation; to survive in a place where everyone sees them as little more than marks to be milked of the little money they have as soon as possible.

“We chose this film because until recently it had never been shown in the UK and we saw this as an opportunity to bring forth a filmmaker whose work to an extent lingered in obscurity,” says Awa Konaté, who curated and will introduce the picture.

“(Sidney) Sokhona’s film in its blurring of ethnography, fiction, and documentary offers an incisive reading of the structural disparities that shape the lives, and experiences of black and brown migrant communities. The interconnected mechanisms of citizenship, anti-blackness, capitalism, and migration that it articulates is timeless and remains important to reflect on the current public debates about inequality in this country.”

In every city these expressions of music and art are important. It’s how we put out what we are feeling. It’s hard here. Culture, it doesn’t have much support. It’s always at the back of the queue

If these warts and all cinematic cityscapes lean more towards the warts there is also a 3d showing of Long Day’s Journey into Night, a dream-like Chinese drama in 3D and Free Time, featuring images of 1950s New York set to music.

Another such city symphony, this time dedicated to Peru’s capital, is Lima Screams. The music, however, isn’t classic. Its soundtrack is vibrant alternative music scene. You probably won’t have heard of the bands. You may, however, hear shades of Sonic Youth, Joy Division, Kraftwerk and Krautrock, even My Bloody Valentine in their eclectic output.

Lima Screams, with its views of the working city, its sights, its spaces, intermingled with scenes of live music, and also protest, make you want to visit the place. The live shows in small clubs it features are a reminder of what’s been missing for more than a year now, and of the vibrancy that needs to be preserved. “We tried to capture the alternative scene music, the freedom. If I see our film, I get the sensation of something nostalgic. We want life to go back to what it was before, to normality,” says Ximena Valdivia, one of its pair of directors.

The scream of the title has multiple interpretations. There are the protests; the city has witnessed several denouncing violence against women. But there’s also the joyful scream from when music is played live. “The protest shows socially we are unhappy. We have been through a lot. The film has that. It is not only happening in Peru,” Valdivia says.

“In every city these expressions of music and art are important. It’s how we put out what we are feeling. It’s hard here. Culture, it doesn’t have much support. It’s always at the back of the queue. But it is very important to keep it going, to keep these spaces, these venues, no matter what.”

Dana Bonilla, the documentary’s other director, says: “Here if you want to do art you have to do it yourself. It is the scream of freedom.”

We could do with hearing that scream again, preferably live, in a small, sweaty venue somewhere in the centre of a living, breathing, pandemic-free city that’s perhaps giving some thought to some of the issues this series of films highlights.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments