2022 is the year of the vampire – here’s why

This year marks 175 years since ‘Varney the Vampire’, 125 since ‘Dracula’ and 100 since ‘Nosferatu’. David Barnett explores why these terrifying figures endure

It’s the year of the vampire!” declares Christopher Frayling.

He’s certainly got a point when it comes to anniversaries. This year marks 175 years since the first book publication of Varney the Vampire, by James Malcolm Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest, which was originally published in serial form in the Victorian penny dreadful magazines. It’s 150 years since the 1872 release of the gothic novella Carmilla by Sheridan Le Fanu, and 125 years since the daddy of them all, Dracula, first made it into print at the hands of his creator, Bram Stoker. It’s 30 years since Francis Ford Coppola released his lush, epic film version of that, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, starring Keanu Reeves and Winona Ryder. And 25 years since Sarah Michelle Gellar first kicked bloodsucker ass to a college rock soundtrack in the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

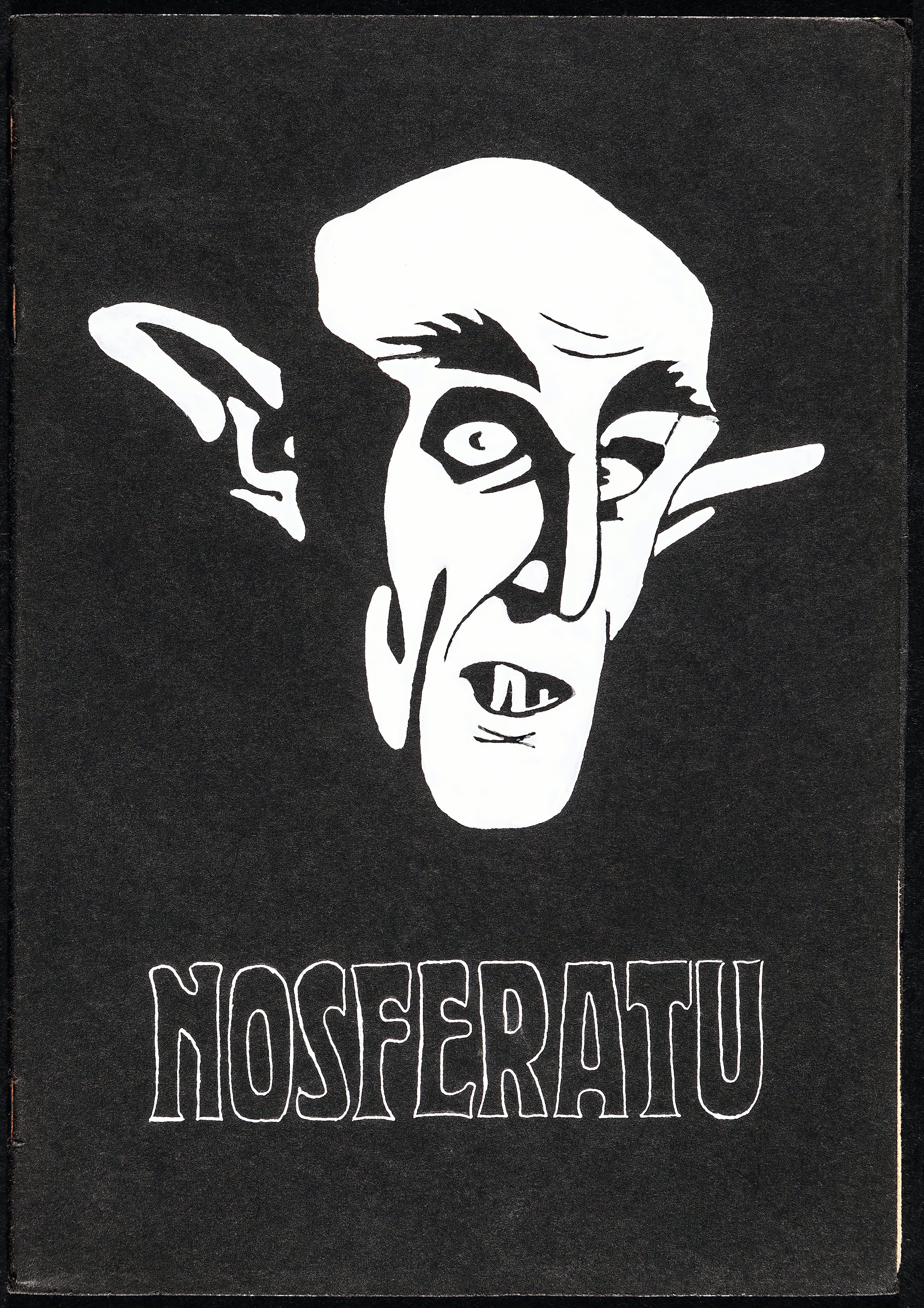

But the anniversary that Frayling is most concerned with is the centenary of the release of the first ever vampire film, 1922’s Nosferatu, and all that followed on the big and small screens. Sir Christopher, to give him his full honours (he was knighted in 2001 for services to art and design education), is a writer with a special interest in the pop culture of the arcane, and his newest tome, out now, is Vampire Cinema: The First 100 Years.

Published by Reel Art Press, it’s a sumptuous coffee table book showcasing film posters and stills from a genre that’s been around almost as long as the cinema itself.

Nosferatu was the first ever vampire film, an unofficial adaptation of Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula, with the vampire renamed Count Orlok and played to stunning creepy effect by Max Schreck.

“It’s not only the first vampire film, it’s really the first horror movie,” says Frayling. Although there were two adaptations of other famous horror novels preceding it — Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in 1908 and Frankenstein in 1910, these were short films and it was Nosferatu, he says, that really kicked off the horror genre.

Frayling says, “In a way, cinema was always eminently suited to horror. People sitting in a darkened room, watching a beam of light put moving pictures on a screen… it’s almost a hallucinatory experience, and right from the beginning cinema was suited to dreamlike, fairy tale, fantastical subject matter. Cinema is total immersion in darkness, watching collective fantasies.”

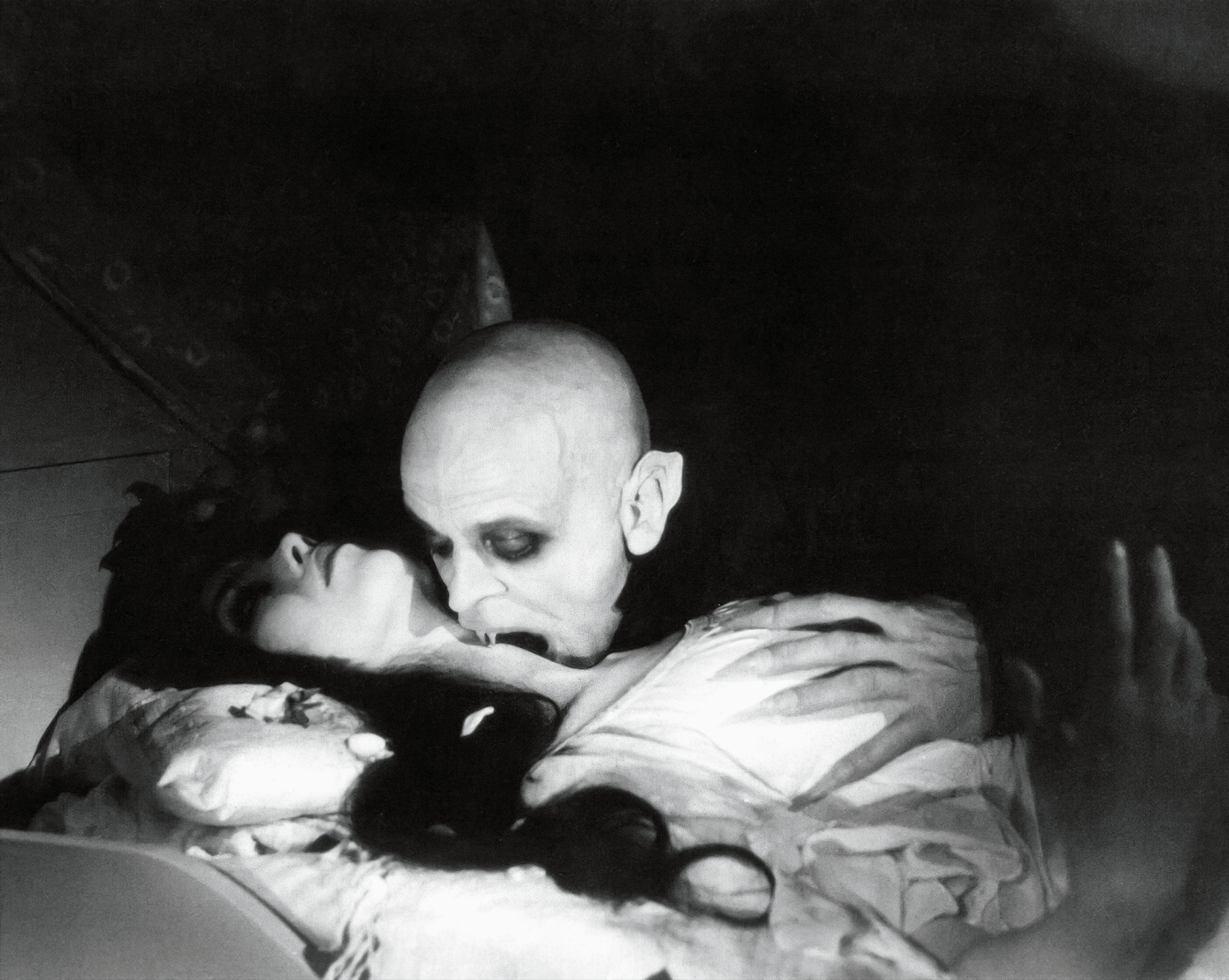

Nosferatu was directed by FW Murnau and produced by Albin Grau’s Prana Film studios in Germany. According to Frayling, the first appearance of the vampire on film was a world away from the much later depictions of the undead.

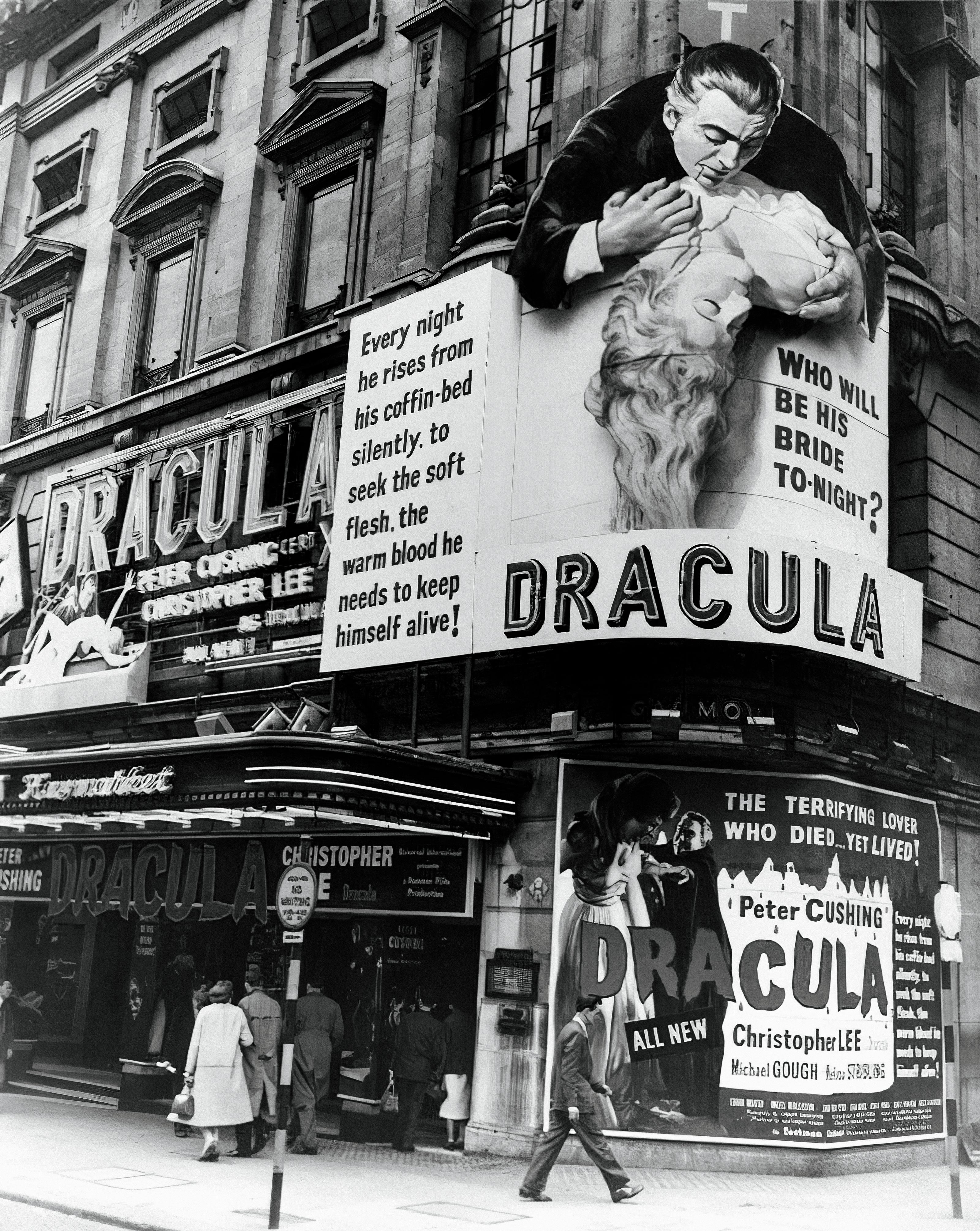

Even a decade later, Dracula had become the handsome, charismatic nobleman in shiny shoes and pressed tails, as portrayed by Bela Lugosi, and that image of the darkly handsome European persisted through many other iterations of Dracula. By the time we got to the 1990s, vampires had become the louchely hedonistic creatures of the night of the 1994 adaptation of Anne Rice’s novel Interview With The Vampire, memorably played by Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt, and even the sparkly, angst-ridden teens of the Twilight saga, the series of films based on the books by Stephenie Meyer.

But Count Orlok in Nosferatu was the mad, bad and dangerous to know vampire you really didn’t want crawling through your bedroom windows at night. Frayling says, “There was nothing desirable or attractive about him, he was not the sexy vampire of later cinema. He was a parasite, he looks like a rodent with his two long front teeth, like the rats he brings with him on his ship.”

We still use Dracula as our cultural touchstone for vampires, and what we think we know about this most curious of supernatural myths. Stoker’s novel was told in entirely epistolary fashion, through diary entries, letters, journals and notes by its principal characters, including young lawyer Jonathan Harker, despatched to darkest Transylvania to act for the mysterious Count Dracula, who wishes to buy property in England.

Murnau and the producers and writers of ‘Nosferatu’ came from more of an occult tradition. They believed in the existence of vampires

The Count indeed comes to the UK, his ship fetching up at Whitby on the North Yorkshire coast, deserted after Dracula has chomped his way through the entire crew on the voyage. Then he starts on the good people of Whitby, including Lucy Westenra, best friend of Mina Murray, who is the fiancé of Jonathan Harker, who has been quite frankly having a high old time of it at Castle Dracula with the Count’s coterie of vampiric women.

Enter into the fray Abraham Van Helsing, doctor and vampire slayer who with the assembled cast sets out to despatch Dracula before he can use London as his all-you-can-eat buffet.

That basic scenario has been the basis for a huge number of the vampire movies that we’ve had in the past century, whether direct adaptations or continuations of the Dracula story, or unofficial takes on it, such as Nosferatu.

But the vampire has endured and changed with the times. And often that is allied to human frailties and concerns. “The difference between Nosferatu and the novel Dracula is that Stoker was basically writing at the time the equivalent of a techno-thriller,” says Frayling . “Like the sort of thing Michael Crichton would write today. He had up-to-the-minute technology, typewriters, phonograph recordings, blood transfusions. Winchester rifles.

“Murnau and the producers and writers of Nosferatu came from more of an occult tradition. They were occultists, they believed in the existence of vampires. And that’s why they presented vampirism as something more creepy, more of a plague.

“And what you have to remember is that in 1922 the audience was recovering from the effects of Spanish Flu. The idea of this horrible plague of vampirism from abroad resonated with them.”

And that’s something that has been repeated at different points in history, the linking of vampirism with some kind of plague or pandemic. Frayling says, “In the 1980s, there were more than 150 vampire films made. You and I will not have seen most of them, but why so many? It was a reaction to the Aids pandemic. This idea that an illness could be passed along by an exchange of bodily fluids… it was terrifying in the 1980s, and that fed into the vampire myths of the time.

“Then we look at the last couple of years, with the Covid pandemic. And there’s even the theory that it started with bats. Will we soon be seeing the first vampire films that are inspired by the Covid years?”

Vampire cinema embraces much more than just horror. The social commentary and feeding the fears of the Aids years, for example. The romanticism of Twilight. And comedy, too, with 1979’s Love At First Bite, in which George Hamilton’s debonair vampire goes looking for love in modern-day New York, and Leslie Nielsen hamming it up in Mel Brooks’ 1995 parody Dracula: Dead and Loving It.

“The 1940s particularly saw the rise of the vampire comedy, through films such as those starring Abbott and Costello,” says Frayling. The 1948 movie Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, despite not giving Dracula top billing, starred Bela Lugosi, doyen of the Universal horror films, in his recognisable role as the Count. “It was a time of war and audiences perhaps wanted something lighter,” adds Frayling.

The vampire itself has mutated and evolved during that time as well. We have a set of assumptions about vampires, cherry-picked and gleaned from the plethora of movie portrayals. They hate garlic. They can only be killed by a wooden stake through the heart. The sun’s rays reduces them to a pile of ash. We get hardly any of that from Bram Stoker’s novel. In that, Dracula could quite easily walk in daylight, though it did weaken him. It was Nosferatu that added that and, by the 1960s, all that was often needed to defeat him was to open the curtains. The band of brave heroes who despatch Dracula in the book do so with knives. By the time of Buffy the Vampire Slayer in 1997, a well-placed stake is required to turn them into a cloud of dust.

Some films have embraced all the tropes, perhaps none more so than 1987’s Lost Boys, in which Kiefer Sutherland’s motorcycle-riding bad-boy vampires are eventually given their comeuppance through baths full of garlic, water pistols filled with holy water, and sharpened wooden fence posts.

Halloween sees a multitude of vampire costumes because it’s such a recognisable trope. You can even put vampires in your film without even mentioning the word vampire… take the cult classic The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), in which Tim Curry’s Frank N Furter is a corset-and-high-heels—wearing homage to the mad scientists of the golden age of horror cinema, an alien from the distant galaxy of Transylvania.

Interestingly, Rocky Horror fans routinely turn up to cinema and stage show performances in costume… and that’s nothing new. At the March 1922 premiere of Nosferatu the audience were asked to dress up in vampire costumes.

Frayling’s book takes in the whole gamut of vampire movies, sumptuously illustrated with film posters, including curiosities such as 1972’s Blaxploitation flick Blacula and the well-regarded TV adaptation of Stephen King’s 1974 novel Salem’s Lot, which revitalised the vampire myth by setting it in modern-day Maine.

“The vampire keeps changing,” says Frayling. “And it has become a more central character, rather than the monster to be killed. Dracula the novel was made up of letters and journal entries from everyone except Dracula himself. Anne Rice’s book Interview With The Vampire, and later the film, switched this around and put the vampire at the centre of the story. Mark Gatiss did it as well in his BBC series Dracula, giving the character much more focus and dialogue.

“We have seen the vampire evolve from blasphemous creature, in Dracula and Nosferatu, to lost outcast, in Interview With The Vampire, to soulmate and love interest, in Twilight and Buffy.”

Frayling’s book covers the Hammer Film years, of course, when the British studio ruled the vampire genre with Christopher Lee as the red-eyed, darkly evil count, and Peter Cushing as his nemesis Van Helsing.

And he treats with equal respect all film iterations of the vampire, taking in the Marvel comics outings such as Blade, starring Wesley Snipes, and the much-maligned Morbius, released this year.

Morbius is perhaps the latest entry into the vampire films canon, and quite fittingly gave a little call-back to where it all started a century ago, which all but the eagle-eyed might have missed. The ship on which Morbius takes to sea to safely conduct his experiments is called the Murnau — the name of the director of Nosferatu, the first vampire film, in 1922. Morbius is the newest vampire film, but it won’t be the last.

“I called my book Vampire Cinema: The First 100 Years because I’m convinced there’ll be a second hundred years, it’s such an enduring cinematic tradition,” says Frayling.

Nobody reading this will be around to see any follow-up book that comes out in 2122, sadly… unless, of course, we find ourselves in some quiet, misty country lane this Halloween, and a cloaked shape looming up in front of us…

‘Vampire Cinema: The First 100 Years’ by Christopher Frayling is published by Reel Art Press and is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments