How the west’s relationship with China unravelled

Five years ago UK relations with China entered a ‘golden era’, but their decline has led to the Huawei U-turn and a docile acceptance of US interference in UK sovereignty. This is how it happened, writes Mary Dejevsky

On 14 July, the culture secretary, Oliver Dowden, stood up in the House of Commons and gave a statement that amounted to one of the most screeching foreign policy U-turns to have been made by any British government in recent times.

He announced that the UK was not only reversing its decision to involve the Chinese telecoms company Huawei in the development of this country’s 5G capability, but that UK telecoms operators would have to strip all Huawei 5G-related kit out of their networks by 2027. This means that older components will probably have to be removed, too, and could spell the end for Huawei’s involvement in the UK market for telecoms infrastructure.

The cost of this decision was perhaps optimistically estimated to be “up to £2bn”. More to the point, Dowden said, it could also result in an delay of “two to three years” in the roll-out of 5G – a blow for a government committed to radically improving the country’s connectivity and to free-market competition. It was also a very far cry from the tone of the UK’s dealings with China five years before.

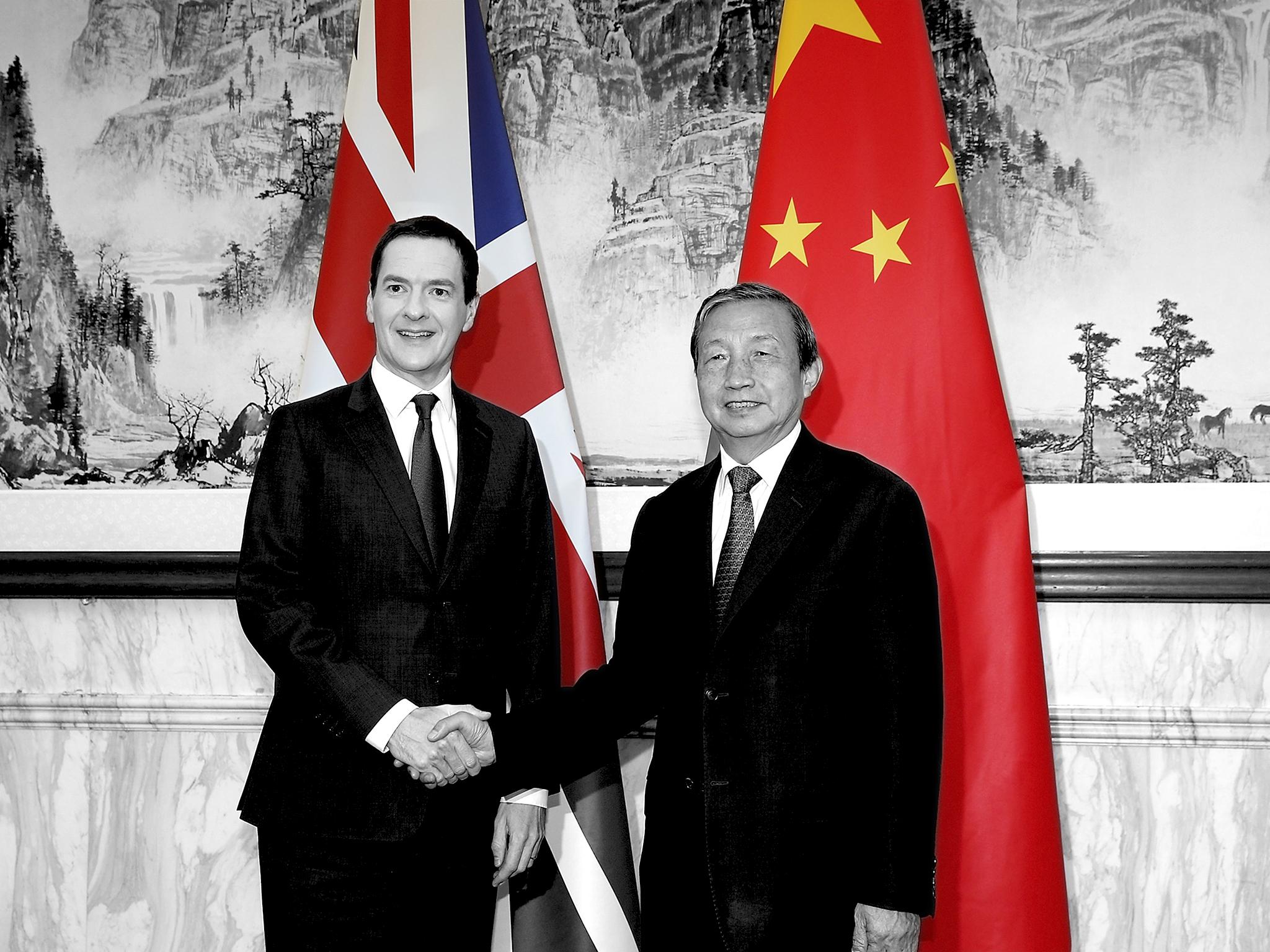

In September 2015, the then chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne, had returned from a high-profile visit to China where he had concluded a clutch of billion-pound trade deals and hailed the start of a “golden era” in Sino-British relations. Challenged by British reporters as to why he had not raised questions of democracy or human rights, Osborne had stressed the potential of the commercial relationship and insisted that such differences were best aired in private. The next month, China’s president, Xi Jinping, was treated to a full-dress state visit to Britain, that also included a matey pint with the then prime minister, David Cameron, at his local pub.

In retrospect, 2015 can be seen as the high point of UK-China relations – a point that may not be reached again for a very long time, if ever. Within the year, the Cameron-Osborne duo were gone, thanks to the Leave vote in the 2016 EU referendum, along with their Sino-enthusiasm. As a security-minded former home secretary, Theresa May took a more guarded position and called for a review of Chinese financing of the Hinkley Point C nuclear power station. No changes were made, but it was a straw in the wind.

By last summer, when Boris Johnson took over as party leader and prime minister, misgivings about the UK’s closeness to China were growing on the Conservative back benches. By January, having secured his own huge electoral mandate, Johnson faced a major revolt. After what was essentially a high-noon National Security Council summit on the issue of Huawei, Johnson announced a compromise. The Chinese company would be allowed to bid for 5G hardware contracts, but its activities would be heavily circumscribed. It would be classed as a “high-risk vendor” and its market share would be capped at 35 per cent per operator – far less than Huawei had anticipated. That partial swerve away from Huawei was completed with Oliver Dowden’s statement on 14 July.

This whole saga, however, is about much, much more than either the UK’s telecoms capacity or its broader trade policy. And the contrast between the sunny optimism of 2015 and the wariness of today reflects not just the UK’s changes of government. It also reflects changes in China, changes in the way China is perceived outside its borders (not just by the UK), and changes in the whole international landscape, including Brexit, Donald Trump, and the growing rivalry between China and the United States.

From the perspective of the UK, it may be simplistic, but not far from the truth, to see the government’s U-turn on Huawei as the latest round in a perennial struggle between Sinophiles and Sinophobes. This struggle is hardly unique to the UK, but it is perhaps sharper here than in some countries for particular reasons of our history and politics.

So long as China appeared weak and self-absorbed, the divergent opinions could remain largely in the groves of academe, with the admirers of China’s ancient and glorious civilisation, its culture and its art, on the one hand, and on the other, those who saw it as a potential threat and warned of a latter day “Yellow Peril”. As China freed up its economy through the 1980s, however, and started to look outwards again, the sheer size and strategic significance of its territory, its billion-plus population and the near-miraculous pace of its economic growth launched it back into the international mainstream.

The end of that decade was marked by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. For the countries generally termed “the west”, the chief effect was to redraw the map of Europe and underline the global pre-eminence of the United States, free-market capitalism and western-style democracy. China, though, took another lesson. It blamed the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, for unleashing chaos when he relaxed the Communist Party’s hold on power, and vowed to take the opposite approach.

It continued to reform the economy, introducing many elements of the free market, but made no concessions whatever on one-party rule. When a new generation tried to force the pace of democracy and a million mostly young people occupied Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, the authorities crushed their aspirations by force.

This was in June 1989, even as communism was being rolled back all over Europe. More than 30 years later, China’s Communist Party is still in charge, and Beijing has demonstrated that – contrary to the conventional western wisdom – democracy does not have to be a pre-condition for prosperity. Stability and order, it would argue, are more important.

While ministers tended to see China as a huge and fast-growing country to be cultivated, others warned about becoming dependent in any way on a potential rival and adversary

The assault on Tiananmen Square prompted a horrified west to ostracise Beijing. But it came around relatively quickly to an acceptance that China was too big and growing too fast to ignore. With more than 1.2 billion people and annual growth mostly in or near double figures, China had gone from being a poor country to an upper middle-income country and a sought-after economic partner in the space of 30 years. The UK, naturally, wanted a slice of China’s enormous and growing market, and China was looking for safe places to invest its new wealth. For David Cameron and George Osborne the potential benefits of courting Beijing were clear.

Theirs was the classic mercantile approach that saw China as an exponentially rising power and trade as the key to mutual benefit; any desirable changes to the political system could, and surely would, come later. In an echo of Harold Wilson’s drive to encourage British children to learn Russian as the superpower space race reached its height (gratuitous fact: I was one), Osborne exuded almost missionary zeal about China as the land of the future, earmarking money for Mandarin to be taught in schools.

The centrality of trade to the UK’s China agenda was only reinforced after the vote to leave the EU, with China seen as fertile ground, especially for UK services. By 2018, however, some less comfortable aspects were impinging. One was what some saw as a double standard – the general free pass granted to China on the “values agenda” that featured prominently in the UK’s policy towards many other countries. Another was the extent to which Chinese interests had quietly penetrated the UK market.

At this point, China’s annual investment in the UK was US$6bn (£4.5bn) and growing. Nor was it just the telecoms conglomerate Huawei – which China insists is a completely private company, albeit one that thrives in the ecosystem of China’s one-party communist state. Its General Nuclear Power Corporation was approved as a partial funder for eight new nuclear power stations. More than 100,000 Chinese students were attending UK universities, and China was making endowments to academic institutions and funding Confucius Institutes promoting Chinese culture around the country.

To many, China’s engagement in the UK was a plus. But the sceptics were also piping up. While ministers tended to see China as a huge and fast-growing country to be cultivated, others warned about becoming dependent in any way on a potential rival and adversary, with a very different world view and very different values from ours. China, they noted, was a power with a capacity for extreme cruelty and deviousness and a penchant for stealing other people’s ideas. If it ever achieved global domination, it would not create a world that non-Chinese, still less westerners, would be comfortable living in.

So long as UK-China relations were seen as to be mutually beneficial, this view was muffled. Even so, the welcome the UK extended to Chinese interests was unusual. Elsewhere in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) it would have been almost unthinkable for China, or indeed any non-allied foreign country, to gain a hold in such critical sectors as telecoms or nuclear power. The UK, in contrast, revelled in the openness and light regulation of its market, which were prized as offering a commercial edge.

In fact, the way in which Huawei was able to gain such a hold in the UK market was investigated by the Commons Intelligence and Security Committee as early as 2013, but the government judged that the pluses outweighed the minuses. As recently as the turn of this year, UK intelligence chiefs professed confidence that any security risks from Huawei’s involvement in the UK’s 5G could be satisfactorily managed. Theresa May’s gentle shot across the bows of Chinese investment in the nuclear sector when she first entered Downing Street was no more than that.

By the time Boris Johnson had consolidated his position as prime minister with his own mandate, however, several strands were converging. The time was approaching when the UK would have to make a decision on contracts for its 5G capability. It was also looking for more investment in its nuclear power sector to meet its climate change commitments. The China that made known its interest in increased involvement in both areas, however, also looked a bit different from before. Or, at least, it seemed to be showing a different face from the one it had presented to Cameron and Osborne five years before.

In 2018, term limits were lifted on the post of Chinese president, allowing Xi Jinping, in theory, to remain in office for life and underlining the totalitarian nature of the Chinese state. Purges of officials proliferated and there was a clampdown on broader dissent, which continues.

The harder line from Beijing was extended to Hong Kong, where China made clear its disapproval of protests that had begun over an extradition law, but escalated into demands for democratic reforms. Its more interventionist approach to the former British colony reached new heights with the National Security Law of late June, which severely restricts protests and expressions of dissent.

Over the past year, Beijing has also also been accused of waging a new campaign of repression in its western, largely Muslim, province of Xinjiang, with reports of detentions and “re-education” camps and the enforced sterilisation of women. Trouble in Xinjiang, it is worth noting, has been something of a barometer historically for insecurities felt elsewhere, and it may not be coincidence that the outlook from Beijing now looks less bright than it did.

Across China, the pace of economic growth has started to slow. The one-child policy is also showing its long-term effects, which include an ageing, and in time declining, population, and a gender imbalance in favour of males that could affect domestic stability. The policy was ended in 2015, but its effects will be felt for many decades.

In its foreign policy, too, China has become less friendly. It has become more assertive in its projection of maritime power – an area of particular concern to its neighbours, but also to western countries, which fear a threat to the navigation of sea lanes. Trouble has also erupted, unusually, on China’s land border, too, with an armed clash in May between Chinese and Indian troops in a disputed area of Ladakh. The clash was short-lived and the rights and wrongs unclear. But this was the first border conflict involving China since its border war with Vietnam in 1979.

And then there is the pandemic. Covid-19, the hitherto unknown virus, is believed to have originated in Wuhan, before escalating into a global pandemic. Opinions differ as to whether China behaved responsibly in identifying the virus and sharing information promptly, or whether it concealed the outbreak until it could no longer be hidden. Whatever the truth, China’s international reputation has been damaged, along with its future trade, after the UK and many others discovered the extent of their dependence on China for supplies of medicine and protective equipment.

Taken together, all these changes have altered the international atmosphere around China. Just a few years ago, Xi Jinping was winning plaudits for what was seen as China’s exemplary peaceful “rise” and its deft diplomacy. As discontent in Hong Kong has grown, Covid-19 has spread around the world, and the UK has started to rethink its economic cosiness with China, Beijing has replaced its former velvety reassurances with so-called “wolf warrior diplomacy” – named after a series of patriotic films.

The rhetoric has been particularly uncompromising against the UK, in part perhaps because so many disputes have piled up, in part, too, though, because China has a particular animus against a country that it sees as an antiquated imperial relic, guilty of exploiting China’s weakness in the 19th century “opium wars”. The spectre of gunboats is summoned up all over again on the recent occasions when the UK has – perhaps foolishly – talked of sending warships to help patrol the South China Sea.

I doubted very much, for instance, that a Russian company, say – of any type – would have been allowed to gain the market dominance enjoyed by Huawei

It can be debated whether China has become more assertive as a result of its increasing wealth and confidence (which appears to be the international consensus), or whether the change reflects something else: apprehension in Beijing, perhaps, that its rise may be stalling and its neighbours – India, first of all – become bolder in defence of their own interests.

And here the United States comes in – because, if there have been changes in the UK and China in their approach to the world over the past five years or so, they are minor compared with the drama that has erupted in US-China relations, where Donald Trump has initiated an all-out trade war.

For some, this is to be seen as the first skirmish in what is destined to become a full-blown battle for global supremacy, with the United States as the declining power – a Sparta to China’s ascendant Athens. Others see Trump’s protectionist brand of “America First” as the continuation of a gradual US retreat from global leadership that will precipitate a global free-for-all.

It has to be said, though, that in launching his trade war with China, Trump hardly had to bend a reluctant US establishment to his will. There has been a strong Sinophobic tendency in the US Congress for the best part of 30 years. And while the vast increase in trade with China in recent years might have placated American consumers with mountains of cheap goods, the growing trade imbalance had long prompted calls for action.

Many other countries were discreetly grateful, too, that someone was finally calling China to account for stretching World Trade Organisation rules, for the threatening noises it was making about restricting navigation in the South China Sea, and the stealthy growth of its influence across Asia and into Europe through a new Silk Route, called the “Belt and Road Initiative”. In challenging China in his inimitable way, Donald Trump was actually tapping into a rich stream of anti-China sentiment that was already there.

Which brings us back all the way to the UK and Huawei. In principle, the UK’s decision on contracts for its 5G network was no one else’s business. It was for the UK government to weigh the advantages of cheap, state-of-the-art technology against possible risks to national security. Someone else, though, had not only an interest but also influence, and that was the United States.

As leader of the Nato alliance and the intelligence grouping known as “Five Eyes” (the other three being Australia, New Zealand and Canada), Washington saw the UK’s reliance on Huawei as a potential threat to the security of the whole. If the UK proceeded with the 5G contracts, it warned, it could forfeit its cherished membership of “Five Eyes”. Not only this, but with Brexit on the horizon, trade talks with the EU going badly and trade prospects with China already soured by Hong Kong, the UK saw the US as the most likely partner for an early free trade deal. For London to defy the US over Huawei risked slowing the prospect of such an agreement, if not negating it altogether.

The final blow to any UK arrangement with Huawei came when the US imposed sanctions on China that would make it almost impossible for the company to produce the computer chips needed for 5G. Shortly before the culture secretary announced the UK’s reversal of its policy on Huawei, the National Cyber Security Centre – a branch of the intelligence-gathering service, GCHQ – updated its view that UK intelligence could manage any security risks with Huawei to take account of the effect of US sanctions. Better not, was its new advice.

This lent cover to the UK’s policy U-turn, but it hardly disguised the reality that the UK had changed a major trade decision, with potentially damaging implications for relations with another major power, essentially at the behest of Washington. So much for the defence of national sovereignty and that Brexit pledge to “take back control”. This is where things stand now.

UK telecoms operators – chief among them BT, as the most dependent on Huawei – are casting around for other suppliers, with a government warning ringing in their ears not to become too dependent on any one source and the knowledge that the global leader is effectively out of the running. BT signed a contract in April that would make Swedish company Ericsson its “core” 5G supplier, and it reportedly has a smaller contract with the US company Adtran.

The UK government is also trying to interest other members of “Five Eyes”, or a broader group that would include South Korea and Japan, to collaborate on fast-tracking a joint telecoms strategy – which looks very like an admission that the Chinese telecoms giant was allowed to steal a march on the west in a key hi-tech sector and that the UK, for one, has some catching up to do. As for the wider fall-out, the UK may or may not have paved the way for a trade deal with the United States, but relations with China – so promising only five years ago – lie in shreds.

If you ever take the motorway past Reading, you cannot but notice a high luminous tower with the name Huawei emblazoned on top. It dominates the city’s outskirts as seen from the M4. When I first saw it, I could not help but muse on what it said about the concessions the UK had made to China. I doubted very much, for instance, that a Russian company, say – of any type – would have been allowed to gain the market dominance enjoyed by Huawei, let alone in an arguably strategic sector. Yet here was a company based in a one-party communist state positively boasting of its dominance to all-comers. Each time I pass Reading on the motorway now, I wonder whether that tower is quite as permanent as it looks.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments