Can Istanbul’s mayor save democracy from the authoritarian right?

For 25 years Istanbul has been controlled by one political party and its antecedents. Borzou Daragahi meets the new mayor and asks whether he can transform the politics of Turkey and turn the country into a model for democratic reform

The black minivan arrives and the awaiting crowd comes alive, converging around it. They hold up mobile phone cameras and rush forward, cheering as the mayor of Istanbul emerges, shaking hands with officials and greeting the dozen or more constituents who have gathered in front of the local government headquarters of Sultangazi, one of the 39 districts that make up Istanbul.

A compact man with an elfish smile, the 49-year-old Ekrem Imamoglu appears a tad overwhelmed as voters beseech him with requests and complaints that range from being fired from their civil service jobs to needing social assistance. An elderly woman pushing her disabled son in a wheelchair pleads for help to care for him.

“Give me time,” he insists. “I have just started.”

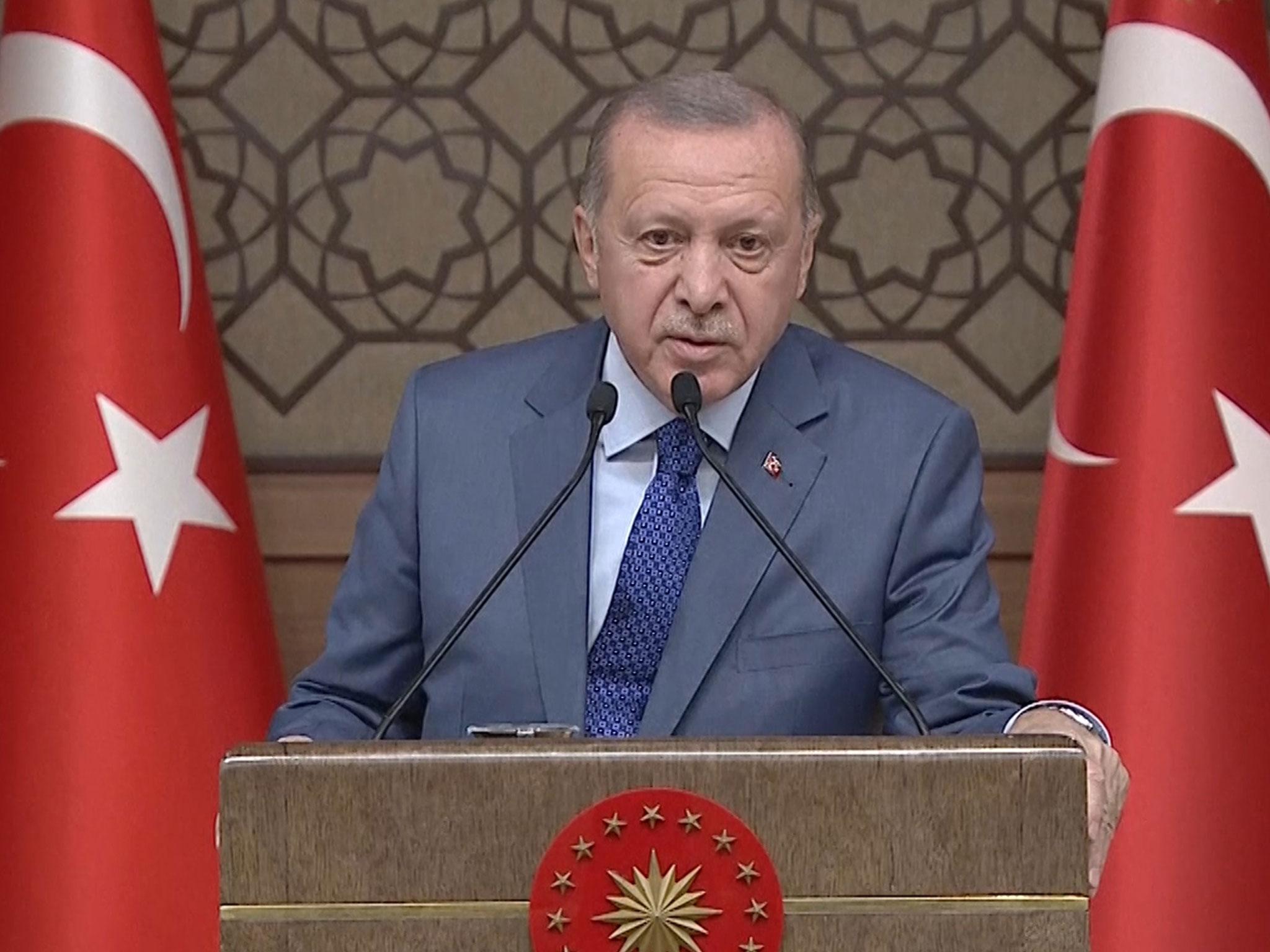

For 25 years Istanbul has been controlled by one political party, Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party, and its antecedents, under the dominion of one man: Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey’s president. He launched his career as Istanbul’s reform-minded mayor, only to become the paradigmatic right-wing populist, drifting deeper into authoritarianism over the past decade or so.

But after a narrow election win last year that was disputed by the AKP, followed by a massive victory over the ruling party’s candidate in a subsequent vote, Imamoglu went from district mayor of an obscure part of Istanbul to mayor of the entire municipality, launching a new era for the city of 16 million people. He could also possibly transform the politics of Turkey, and even serve as a democratic model against the surging right-wing authoritarians across the world as well as the high-tech policing tactics used to maintain control over large Asian cities.

“We have another way,” Imamoglu says during a wide-ranging interview in an office tucked into an Istanbul convention centre along the Bosphorus. “We see cities as centres for equal citizens,” he says. “We promote equality among all citizens, and we believe we will be establishing a very strong democracy and will be applying all kinds of methods and steps to promote democracy in our city.”

For now, six months or so into the job, he is still listening to constituents, struggling to balance public expectations with his limited capabilities. “I know what people want, what Istanbul needs,” Imamoglu says. “Of course I know that people are dealing with unemployment and poverty. I always try to do my best to show my interest, to show them that I am aware of these problems.”

Will Istanbul become an Orwellian surveillance and enforcement state like the major cities of Asia, or will it pursue a more democratic and pluralistic vision?

Istanbul is a massive and sprawling beast, stretching from the beaches of the Black Sea to the shores of the Sea of Marmara, from the forests to the north of the city, to the sprawling hillsides full of apartment blocks and villas crowded around the Bosphorus, and neon-lit skyscrapers jutting out over Levent and Atasehir. The Marmaray, the world’s first transcontinental subway line, stretches 48 miles, tunnelling beneath the Bosphorus to connect the city’s Asian and European sides.

It is the largest city in Europe. At more than 2,000 square miles, it is bigger than the US states of Rhode Island and Delaware, and has a population of at least 16 million that rivals the entirety of the Netherlands, and dwarfs many European countries.

Yes, it is famously a crossroads between Europe and Asia, straddling both continents, but it also links the Middle East, the Balkans and the Caucasus. In recent years, as it has been flooded with migrants, refugees and tourists from the Arab world and Iran, and it has arguably supplanted and transcended Cairo and Dubai as centres of Middle East commerce and culture.

It is a city whose dimensions, historical and geographic importance and potential for unruliness make it a test case for the future of urban spaces: will it become an Orwellian surveillance and enforcement state like the major cities of Asia, or will it pursue a more democratic and pluralistic vision?

Already, under AKP rule, Istanbul is one of the most heavily monitored cities in the world, in part because of a fear of terrorism from Islamic extremists and Kurdish separatists. Multiple security forces patrol the streets and closed-circuit television cameras installed throughout the city monitor nearly everything – as demonstrated by the unspooling of vast reams of footage following the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

“This city is a mass of different perspectives,” says Canan Kaftancioglu, the chain-smoking politician in a leather jacket often described as Imamoglu’s intellectual inspiration. Only last year, she faced prosecution for social media posts made seven years ago that were critical of the government. The charges have been dropped, and she now serves as head of the Istanbul branch of the People’s Republican Party (CHP), Imamoglu’s party. She speaks during a late morning meeting at an outdoor cafe in Moda, a wealthy district along the Bosphorus, on the city’s Asian side.

“You need the cultural perspective, the urban planning perspective, and the social-democratic point of view,” she says. “I don’t think that the security dimension alone is going to work if you’re going to govern a city.”

Development has exploded over the last 30 years, and many worry that the new buildings won’t withstand the looming earthquakes that have plagued the city for millennia

In fact, Istanbul’s problems are many, and often hidden from plain sight. Muhtars, the most junior locally elected officials, describe epidemics of domestic violence directed at women and children, and drug abuse, including consumption of a synthetic cannabis called “bonsai” in underprivileged neighbourhoods of the city.

On the surface, Sultangazi is a bustling and peaceful lower-middle class neighbourhood. But it has a history of violence pitting residents against police, and occasionally each other. It is a colourful amalgam of different peoples from Turkey and the region, with crisscrossing social currents, and potentially explosive politics.

With a population of half a million, it has long been a stronghold of Kurdish activists with ties to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party, or the PKK, but locals say it is also a major hub for narcotics. For years the “leftists” checked the drug traffickers, dictating to whom and what they could sell or move. But since the government launched a crackdown on the PKK and its affiliated groups five years ago, the traffickers have grown unchecked. Gangsterism is out of control. “You see the luxury cars, the jewellery,” a jaded local reporter tells me.

A large but undetermined number of Syrian refugees, mostly ethnic Kurds, have made their homes in Sultangazi, adding to the tensions, and needs.

Turkey’s economy is floundering, with joblessness and idleness among the young on the rise. Neighbourhoods such as Sultangazi are especially hard hit. If it’s not drugs, it’s illegal betting on football or basketball games. They play against their friends so if one wins, the other loses, and fights break out. Suicides are up.

There are also longstanding problems that plague many of Istanbul’s newer districts, which lie far from the tourist draws of Istiklal Street, the Hagia Sophia and the Strait of Bosphorus. Development has exploded over the last 30 years, and many worry that the new buildings won’t withstand the looming earthquakes that have plagued the city for millennia.

Of course, traffic is a big problem; new roadways need to be built. In 2000, Istanbul had about one million cars. Now the number has jumped to nearly 4.25 million. No subway lines yet reach Sultangazi, and public and private banks – many close to the government – have refused to lend the city money for development projects since Imamoglu came to power, the mayor has said.

Childcare and daycare centres are what we need, more green spaces, programmes that allow women to feel more secure and free

Urban planners and environmentalists also worry about the pace of development in the city, specifically massive highways and bridges built under Erdogan’s rule. The most controversial project is the proposed Canal Istanbul, an attempt to build a waterway deep within the European side of the city to connect the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara while bypassing the Bosphorus. Already land has been sold and deeds transferred around the proposed site of the 28-mile-long waterway in a haze of deals with foreign and domestic companies, including the president’s son-in-law, that are part and parcel of the state patronage that helps the AKP maintain its support among business leaders.

“These are not transportation projects; they are battering ram projects meant to open up spaces to development,” says Asli Odman, a professor of urban planning at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University in Istanbul. “This opens the door to construction in agricultural and biodiverse spaces. The major problem in Istanbul is the ecological limit which we have surpassed in the last decades. And there is no turning back.”

It was anxiety over runaway development that sparked the 2013 Gezi Park protests against Erdogan and his party, ultimately creating a movement that propelled Imamoglu to the mayoralty. Imamoglu says he’ll fight Canal Istanbul with all the resources he can muster. Kaftancioglu says Istanbul doesn’t need any more big projects, which have included massive bridges, tunnels and highways. “We need small touches,” she says. “Childcare and daycare centres are what we need, more green spaces, programmes that allow women to feel more secure and free.”

Among the projects already pursued, for example, are programmes to employ more women parking attendants and bus drivers, to make the city more female-friendly. For now, Imamoglu’s main solution to nearly everything is simple: just listen. He’s organised roundtable groups of stakeholders on topics ranging from the Romani population and Syrian refugees, to tourism, education and the environment. Imamoglu also makes regular visits to the districts, meeting with constituents as well as local officials, like his visit to Sultangazi.

“We will also be establishing a task force for the cities’ different religions,” he says. “As the mayor of Istanbul, I will be moderating the discussions. I see myself as a moderator.”

He speaks of establishing “democratic platforms” drawing in citizens to discuss and propose solutions to problems ranging from the city’s lack of green spaces to its earthquake preparedness.

He has been criticised for going on a ski trip with his family in the immediate aftermath of the recent earthquake in Elazig

“Nobody will be left out, no subject will be left out,” he says. “It will be something beyond politics, including every part of society for the management of Istanbul.”

At times Imamoglu’s vision sounds similar to the “deliberative democracy” bodies established in Belgium and elsewhere to draw ordinary citizens into the processes of governance and politics, at least in an advisory capacity. He has committed to increasing transparency; he began ordering municipal assembly meetings to be broadcast live for the first time. Nearly 4 million people tuned in the first time. “I was a district mayor for five years,” he says. “That’s when I saw how communication can be used as a powerful tool.”

During our interview, he brings up an apocryphal tale from the middle ages. Back then, he says, if a slave was able to escape from his masters and make it to a free city, and live there for an entire year without getting caught or in trouble with local authorities, he would be considered a freeman. That’s in part the vision he harbours for Istanbul.

“We don’t see any minority in our city,” he says. “We’re embracing the diversity in our city. And we believe that such an understanding will be adding a new momentum across the world; we will be a role model for the entire world.”

After a meeting with local officials, including the genial AKP district mayor of Sultangazi, Imamoglu heads back into his minivan, again overwhelmed by the crowd that mobs him.

In contemporary Turkey, it is developers or those near the construction industry who seem to gravitate towards politics, as opposed to lawyers, engineers or doctors. With a rumpled suit and tie, the bespectacled Imamoglu looks every bit the developer he used to be, as he fields complaints and concerns. One citizen had his home demolished and needs housing. Another young man wanted a university scholarship. Others just want selfies.

“It is a common thing for the Turkish people that they ask everything from the mayor, although we have a limit to what we can do as mayor,” Imamoglu later says.

Imamoglu is no firebrand. He has roots in the same conservative Black Sea region of Anatolia as Erdogan, and during the interview he speaks of the different cultural and political strains within his own family. He is cautious about his criticism of Erdogan and his party. During an encounter with voters in Taksim Square, one referred to the president as an “enemy,” a label Imamoglu rejected

Imamoglu walks a far more careful line. He describes the refugees as a part of the city, though he says he hopes they end up returning to their homes once there is peace in Syria

“He is not our enemy,” he said. “Maybe he doesn’t like us so much.”

The stakes are high, and Imamoglu knows it. Everyone is watching closely. When Gergely Szilveszter Karácsony defeated the candidate of far-right Hungarian leader Viktor Orban for mayor of Budapest in October, he cited Imamoglu as an inspiration.

But already the AKP and its supporters have trained their sights on him. They have begun a campaign on social media and their own press describing him as incompetent and befuddled, criticising him for being too aloof from the city’s problems and focused on building up his national and even international stature with visits outside of the city -- including to the Brandenburg Gate on the 30th anniversary of the opening of the Wall in Berlin on 9 November.

He has been criticised for going on a ski trip with his family in the immediate aftermath of the recent earthquake in Elazig, and even his own colleagues grumble that pressing Istanbul needs have yet to be addressed. Erdogan continues to dominate public discourse and controls the levers of the budget and security forces. His AKP dominates the city’s municipal assembly and continues to control most of Istanbul’s districts.

Ankara has repeatedly sought to undermine Imamoglu and his allies. In addition to blocking loans from banks, the governor of Istanbul, appointed by Erdogan, recently banned all protests opposed to the Turkish military intervention in Syria. The police, answering to the interior minister, recently cracked down on International Women’s Day marchers attempting to stage a protest along Istiklal Street, a main commercial walkway.

Imamoglu’s supporters are harshly critical of the AKP, whom they accuse of bending the tools of the state to serve their political interests.

“The rule of law is gone, and freedoms are suspended,” says Kaftancioglu. “People are discriminated against because of their identities. The populists and right-wing – most of the problems we have are created by these types of governments.”

Kaftancioglu links the rising tensions between Turks and Syrian refugees to the economic and policy failures of the central government. “The people who live in Istanbul are also suffering from some of the problems as the Syrians,” she says. “When we talk about Syrians we are talking about people who are escaping war. They are also suffering from unemployment. Both are suffering from the same system.

We don’t want one part of Istanbul to be left out. We want to create a place where young people are watched, but not spied upon

But Imamoglu’s own political allies can impede his vision of a shining free city. Though his rhetoric on the millions of Syrian and other refugees sheltering in Turkey has been measured, his CHP allies have repeatedly veered into xenophobia and hostility when speaking about migrants and foreigners, often showing far less sympathy to refugees escaping war than members of Erdogan’s AKP, who have also largely turned on the refugees they once welcomed. Newly elected CHP officials have ordered funds for refugees slashed, barred them from beaches and made it clear they prefer them to leave Turkey.

Imamoglu walks a far more careful line. He describes the refugees as a part of the city, though he says he hopes they end up returning to their homes once there is peace in Syria and strongly hints that he would like some help from the outside world in addressing their needs for shelter, education and healthcare.

“They pose a challenge for us,” he says. “We’re doing our best to find humane solutions to their problems. We’re trying to find new financing models from the EU as a local government so that we can directly help those in need.”

The last stop on Imamoglu’s visit to Sultangazi is the nearby sports complex down the road from the district headquarters, an impressive stadium and outdoor track built to draw the young from the temptations of the streets. Imamoglu and his entourage enter through the rafters. Dressed in martial arts uniforms and tracksuits, several thousand teens, children and young athletes stand and cheer, waving red-and-white Turkish flags .

A child in a white karate uniform shakes Imamoglu’s hand. He hugs several children in wheelchairs, finally looking at ease. Many argued that it was Imamoglu’s natural ability to connect with voters in marketplaces and on the streets during the campaign that elevated him from obscurity to arguably Turkey’s second-most important politician. During the months of campaigning, in a gambit that harkened back to Erdogan’s own early days as an Istanbul politician, he ventured into districts considered hostile to his secular-nationalist CHP, and sought to engage with voters outside his political comfort zone.

“I believe we’ve raised hope for all people,” he says. “We tried to talk to each other in person. We tried to explore each other and get to know each other a little more. And we believe that we went beyond politics, beyond the mayoral elections, we established a very strong dialogue with the people.”

That, he says, is what politicians challenging authoritarians around the world may have forgotten.

“The whole world is now engaged in political conflict and debate,” he says. “They need to remember that we need to establish contact with the people, direct communications. That is what we did during the election process. That’s what gives people hope about democracy and what unifies people.”

Imamoglu finally breaks away from the adults in suits and heads to the podium. “You all look very beautiful and healthy,” he says, in a speech which touches upon themes that he and his team have emphasised since coming to power.

“We want to build a city where the spirit of the sport is everywhere,” he says, looking out at the hopeful, smiling faces of those who are Istanbul’s future. “We want all young people and children to exercise in the city. We don’t want one part of Istanbul to be left out. We want to create a place where young people are watched, but not spied upon.”

This story has been updated to clarify the role of the Justice and Development Party and its antecedents in Istanbul.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments