Will Trump destroy opposition research or will it destroy him?

The days of breaking into the Watergate building in the dark are gone, writes Richard Hall. Opposition research today is more likely to be carried out on a laptop in a cafe. But as politicians continue to lie and research becomes irrelevant, will post-truth politics become the norm?

Opposition research used to be conducted in the shadows – quite literally. The five men who broke into the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate office complex needed flashlights. It’s not called the “dark arts” for nothing. Today, the job is more likely to be done by a millennial campaign staffer on their laptop in a coffee shop. The sheer volume and availability of information online has brought much of the work into the light. And yet, these changes have brought with it a paradox: at a time when opposition research is more prevalent than ever, it may be having less of an impact.

One need only look to the current occupant of the White House to see why. Since his emergence as a frontrunner in the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump has been a constant target of the best opposition research money can buy. Revelations that would have sank any other campaign failed to make their mark – from his bankrupt businesses to his boasts about sexually assaulting women.

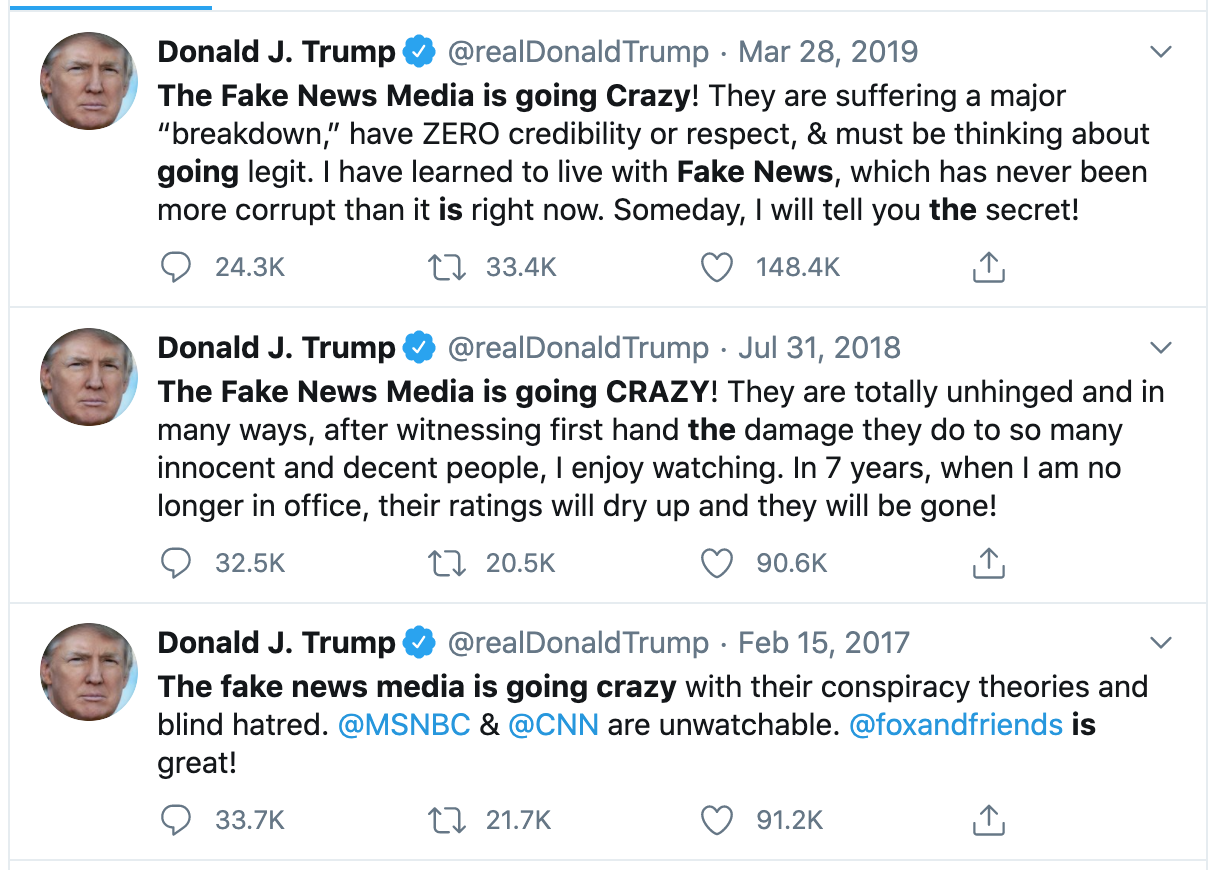

There were clearly many, complicated reasons so many Americans voted for Trump, but his victory changed the game in more ways than one. The impact of opposition research – for so long a central part of any campaign – was blunted. His efforts to foment polarisation and blur the lines between reality and fiction (“Fake news!”) all worked to create a confusing milieu of information and disinformation. The meaningful and trivial became impossible to distinguish.

“Ultimately, opposition research tells people what they need to know when they’re choosing their leaders. So it has positive ramifications,” says Alan Huffman, a researcher with decades of experience and co-author of ‘We’re With Nobody’, a book about the industry.

“But when you look at someone like Trump, it doesn’t really matter to his supporters whether he’s fit to lead, because the key question for most people is whether or not the information they are seeing reflects their perceived notions and their affiliation. And so all of these other questions about what is and isn’t honourable seems sort of quaint.”

Over the last four years, despite a steady drumbeat of scandal hanging over the White House, Trump’s base has remained solid. Not only that, other politicians are starting to take notice and follow his lead. All of which begs the question: does opposition research still matter? And if not, what do we lose if it doesn’t?

At its core, the work of an opposition researcher is similar to that of an investigative reporter. They dig through documents and speak to sources to reveal something that someone doesn’t want to be made public, with the aim of gaining an advantage over a political opponent. That might involve digging through court records to find out if a candidate is up to date on their taxes, or seeking out and talking to someone who claims to have information on a candidate.

I once interviewed a guy sitting on the porch of his trailer with a shotgun because he thought somebody might try to kill him for telling me what he knows

“You never know where you’re going to find information,” says Huffman, who has worked for Democratic and Republican, local and national campaigns over the years. “Everybody knows something you don’t. And even if 99 per cent of it is just junk and conspiracy theories or whatever, there may be one nugget in there of truth that is very important.”

Most opposition researchers are quick to dispel the caricature of their job that makes its way to TV and film (usually a nefarious, private investigator type using questionable methods to destroy a candidate). A lot of the work involves sifting through paperwork and public records. But there have been moments in Hoffman’s career when his work has lived up to the image.

“I once interviewed a guy sitting on the porch of his trailer with a shotgun because he thought somebody might try to kill him for telling me what he knows. That kind of stuff happens, when there’s a lot of power at stake. And so, you know, maybe it will lead you to something and maybe it won’t.”

The depth of the digging into a candidate depends on the level of the race, and the money on offer. Roughly speaking, prices for a thorough vetting by an independent researcher start at around $5,000, and can go up to anywhere between $20,000 and $50,000 for a routine congressional race.

“If you are researching a member of the local school board in New Jersey, you’re not gonna approach that in the same way as you are looking at a US Senator or a presidential appointment, firstly because they don’t have the money to spend on it,” says Huffman. “More importantly, with a school board member, there just isn’t likely much there. But if you’ve got somebody who is at the top level, they’ve had their fingers in a lot of different pies, and there is more incentive on the part of whoever’s hiring you to do the research to invest the time necessary to find out.”

One recent example of this is the allegations against Joe Biden by Tara Reade, who last year accused the presumptive Democratic nominee of sexually assaulting her when she worked on his senate staff in the 1990s. Many people questioned how no opposition researcher had found her and made her claims public while Biden was running for vice-president. Huffman suggests there is a significant difference in vetting between the president and their deputy.

“You get a lot more scrutiny when you’re the guy running for president, especially when you’re running against someone as well funded as Trump, and as aggressive as his people are,” he says. Or, as another industry insider but it, “no one really cares about the vice-president.”

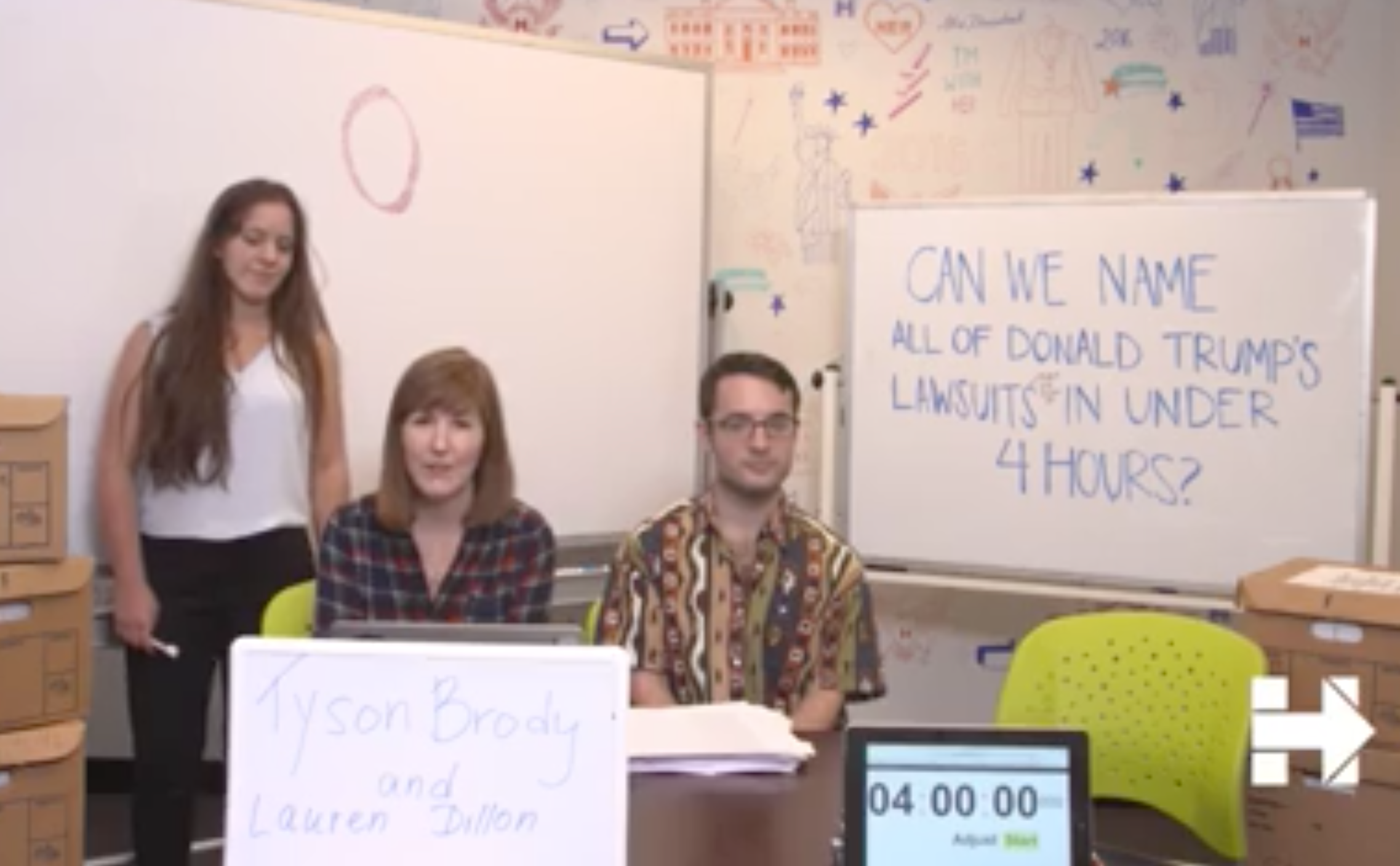

The same methods are also applied by campaigns to investigate their own candidate, both to ensure they are properly vetted and to anticipate any attacks from their opponents. Tyson Brody, a 33-year-old veteran of three presidential campaigns, has done the job from both sides. He served as Hillary Clinton’s deputy research director for the 2016 election campaign, where he was part of a team that compiled research on Bernie Sanders, only to go on to work for the Sanders’ campaign this year.

Opposition research isn’t really about persuasion at the general election level. A lot of times you’re just talking to your own people to rile them up. It’s almost like you’re giving your people a vocabulary

“I believe they thought it was pretty funny,” he says of his reception on the Sanders team. “But for me it was just sort of natural. I dug into this guy, and it turned out I think he’s actually really cool.”

In recent years, campaigns have increasingly turned to in-house researchers like Brody to do the job that an independent researcher might have done before. Brody, who started out as a journalist’s assistant, remotely investigating civilian casualties in Afghanistan, says much of his work is aimed at using publicly available information to build a narrative about an opponent, which is then passed on to the Press in a package or used in the campaign’s own output. While working for Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign, he was involved with research into Mitt Romney and his record as head of the investment firm Bain Capital.

“We got to do all these cool ads based on the headlines about Mitt Romney shipping jobs overseas. He became the vulture capitalism guy,” says Brody. “It came to really define his character for the campaign.”

But, he adds, much of the research done by a presidential campaign is not aimed at winning votes from the other side of the aisle, but rather energising their own base. “The idea that there are silver bullets out there that are going to change people’s opinions on a candidate, it’s just few and far between. Opposition research isn’t really about persuasion at the general election level. A lot of times you’re just talking to your own people to rile them up. It’s almost like you’re giving your people a vocabulary,” says Brody.

There are exceptions to that rule. The 2016 presidential campaign was dominated by two stories that created a goldmine for opposition research. The first was the controversy around Hillary Clinton’s use of a private email server to conduct state department business when she was secretary of state in the Obama administration, together with the leak of a trove of emails from the hacking of her campaign chairman John Podesta in March 2016. US intelligence agencies concluded that Russia was behind the email thefts, which were passed on to Wikileaks.

The hack and leak of the emails had little to do with opposition research, but what the Trump campaign and its surrogates did with that information very much was. Trump-supporting outlets were able to delve into the emails again and again to create new stories and alleged scandals. “It was a whole mixture of things, because it fed into a bunch of narratives about her. You could say that kind of started as a fishing expedition, but then it became something that you could hang lots of research on,” says Brody.

(Due to his work for the Clinton campaign, Brody was mentioned in several of the emails, one of which detailed an attack plan he was working on regarding “Sanders’s muted response to possible tar sand oil travelling through a pipeline that goes through Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont.”)

How it plays out in November is going to have a lot to do with whether or not the truth still matters. If it doesn’t, there’s really no point in doing opposition research, right? Because if nobody cares what’s true and it has no impact on choosing leadership then it’s futile

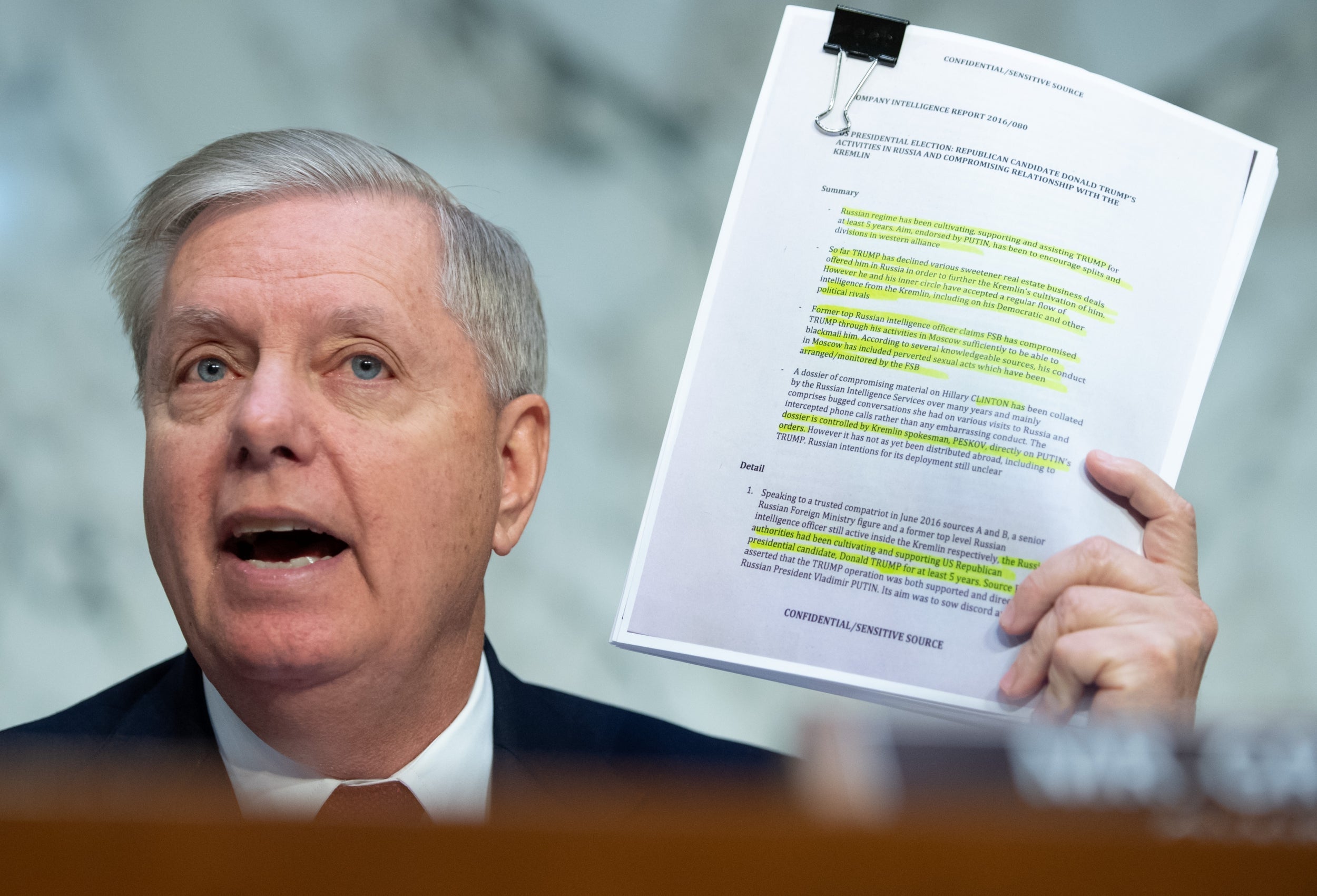

While stories about Clinton’s emails flooded the newspaper columns and television screens, perhaps one of the most infamous pieces of opposition research in recent years was being conducted in the background. Christopher Steele, a British former spy, was delving into Trump’s links to Russia amid mounting evidence that Moscow was working to undermine the election to help Trump win. Steel was working on behalf of a Washington-based private investigative firm named Fusion GPS, which was initially hired by the conservative website Washington Free Beacon. When Trump secured the nomination, the Free Beacon backed off and Fusion secured funding from the law firm Perkins Coie, on behalf of the Hillary Clinton 2016 presidential campaign and the Democratic National Committee, to continue their investigation.

The result of these investigations came to be known as the Steele Dossier. In all, Steele filed 17 reports that made up his final document. Those reports, which began in June 2016 and continued throughout the campaign until after the election, focused on links between Trump’s campaign and the Russian state. They alleged that Russia hacked and released emails from the Democratic National Committee’s server as part of a broader campaign to help Trump win the election, and that members of Trump’s campaign actively collaborated with Russia in that effort. It explored Trump’s deep business interests in Russia, and the many links between key campaign staffers and Russian business and politics.

Many of the details in the dossier remain unproven, such as the most explosive claim that the Kremlin had compromising video tape of the president that it was using as leverage. But Steele was so concerned that he approached the FBI with his findings, which the agency then investigated.

It was a great irony that, despite the efforts that went into the investigation and the potentially explosive implications of its findings, most of it did not become public until after the election. Steele submitted his report in December 2016, after Trump narrowly won the race. Some of his findings were reported in October, but they were vague enough to not make a major impact on the race.

The aftermath of the election, when revelations about the Trump campaign’s links to Russia continued apace, the irony-laced “But, her emails!” meme was born — a reference to the media outcry over the arguably trivial revelations in those emails. But even when they did arrive, they failed to make a meaningful dent on Trump’s approval ratings. A new era of partisanship in America, which has been ruthlessly exploited by Trump, has meant that opposition research and grand narratives about a candidate often fall flat.

“What has happened over the last decade, but incrementally for longer than that, is this whole idea of what is true has changed. Trump has used that to his advantage. He’s the master of it, but he’s not the first,” says Huffman, who adds he had concerns about how some of the information contained in the Steele Dossier was gathered.

Huffman says the foundation of all opposition research is documentation. A researcher’s job is to find information and then present it impartially so that it is unassailable — documents and evidence is key to that.

You’re watching the things that you look for unfolding right in front of your eyes. And I see a lot of people making really stupid decisions that are going to come back to haunt them

“This obfuscation, and making people unsure of what to believe, has undermined the power of documentation,” he says. “And because of social media and particularly social media echo chambers, the whole idea of alternative facts, that is a massive change when your whole job is to determine the documentable truth.”

Democrats have already prepared an avalanche of opposition research to hit Trump with in November’s election. Some operatives reportedly believe that attacks that include a policy record will have more bite. But it is still unclear whether the kind of traditional research will work. Could Trump brush it all off again?

Brody believes that Trump is a “unique beast” in that regard. “I would spend weeks going through legal documents to prove he was charging tenants in one of his buildings for property taxes that he didn’t actually owe,” he says. “It’s a great story. But then Trump would just go out and say something like: ‘It should be illegal to be Mexican,’ and that’s what everyone’s gonna talk about.’”

“I don’t think there’s anyone comparable on the Republican or Democratic side,” he adds.

Some are already warning of a repeat of 2016. The Trump administration is already pushing unsubstantiated claims about Biden and the Obama administration’s role in the investigation into Russian meddling. Republican opposition researchers are delving into the business dealings of his son, Hunter Biden. Could Trump again muddy the waters around his opponent to a degree that makes the differences between them intangible?

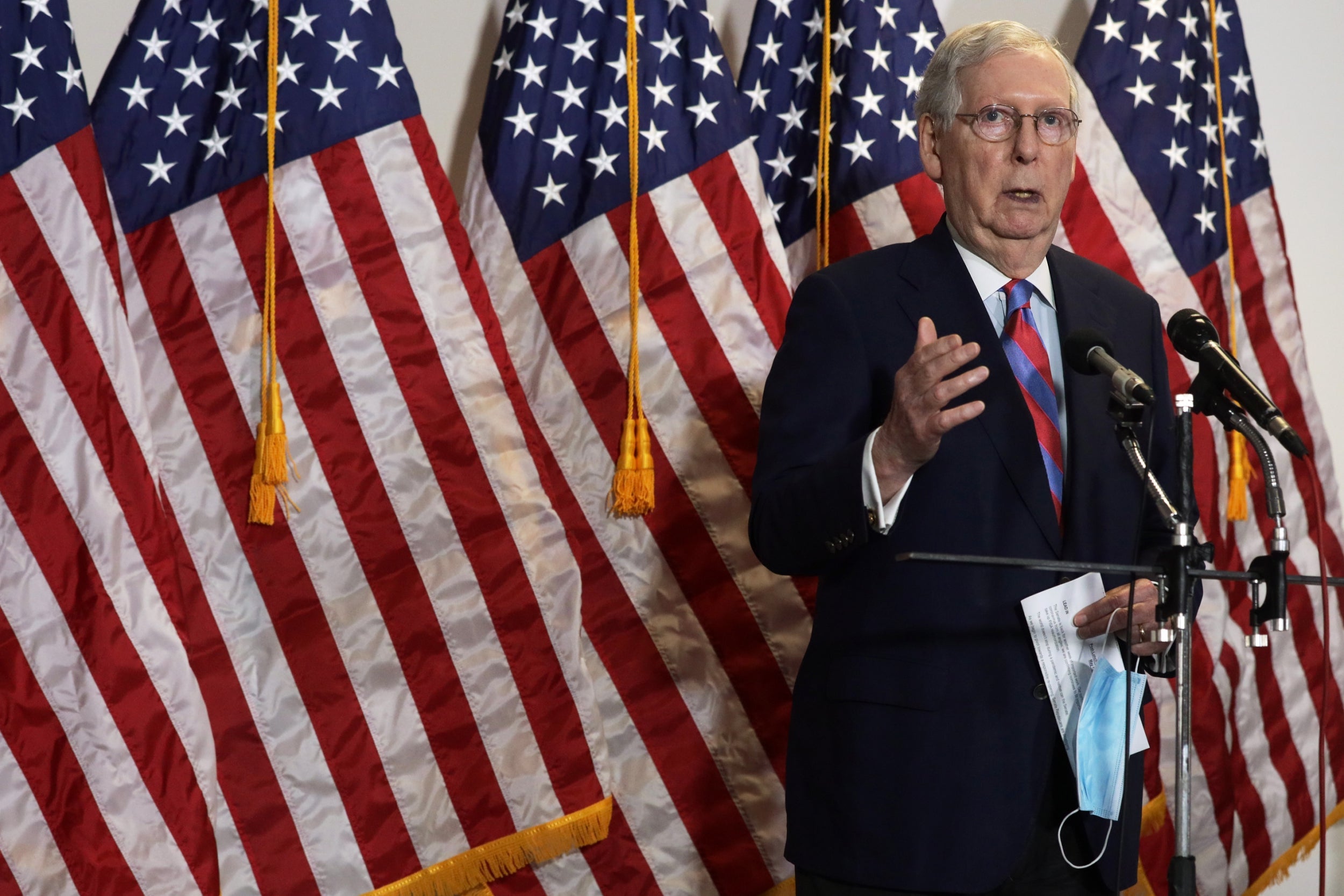

Then there is another danger: what if Trump isn’t unique? “Is the fact that he can get away with this going to translate into other candidates, particularly Republicans, doing the same thing, and also getting away with it? There have been plenty of people like Mitch McConnell who have been following the same template,” Huffman says.

The danger, he argues, is that politicians will choose to undermine and lie to limit the damage of opposition research to a degree they have not done in the past. Such an outcome would mean post-truth politics becomes the norm.

“How it plays out in November is going to have a lot to do with whether or not the truth actually still matters,” Huffman says. “If it doesn’t, there’s really no point in doing opposition research, right? Because if nobody cares what’s true and it has no impact on choosing leadership then it’s sort of futile.”

“But you always have to believe that eventually the truth will out and that people will pay for what they are doing,” Huffman adds, citing the administration’s response to the coronavirus as potentially a deciding factor.

“Now, it feels like you’re watching opposition research in real time. You’re watching the things that you look for unfolding right in front of your eyes. And I see a lot of people making really stupid decisions that are going to come back to haunt them. And they’re not even doing it behind the scenes. You don’t even have to dig for it. They’re doing it right there in the open.”

“Especially now, when you’ve got people dying, the truth matters more than ever. I think something like that just becomes impossible to ignore.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments