How the British became so successful at the Tour de France

Ten years on from when Bradley Wiggins became the first Briton to win the Tour de France, Mick O’Hare looks back to Tom Simpson, the first Brit to ever wear the yellow jersey

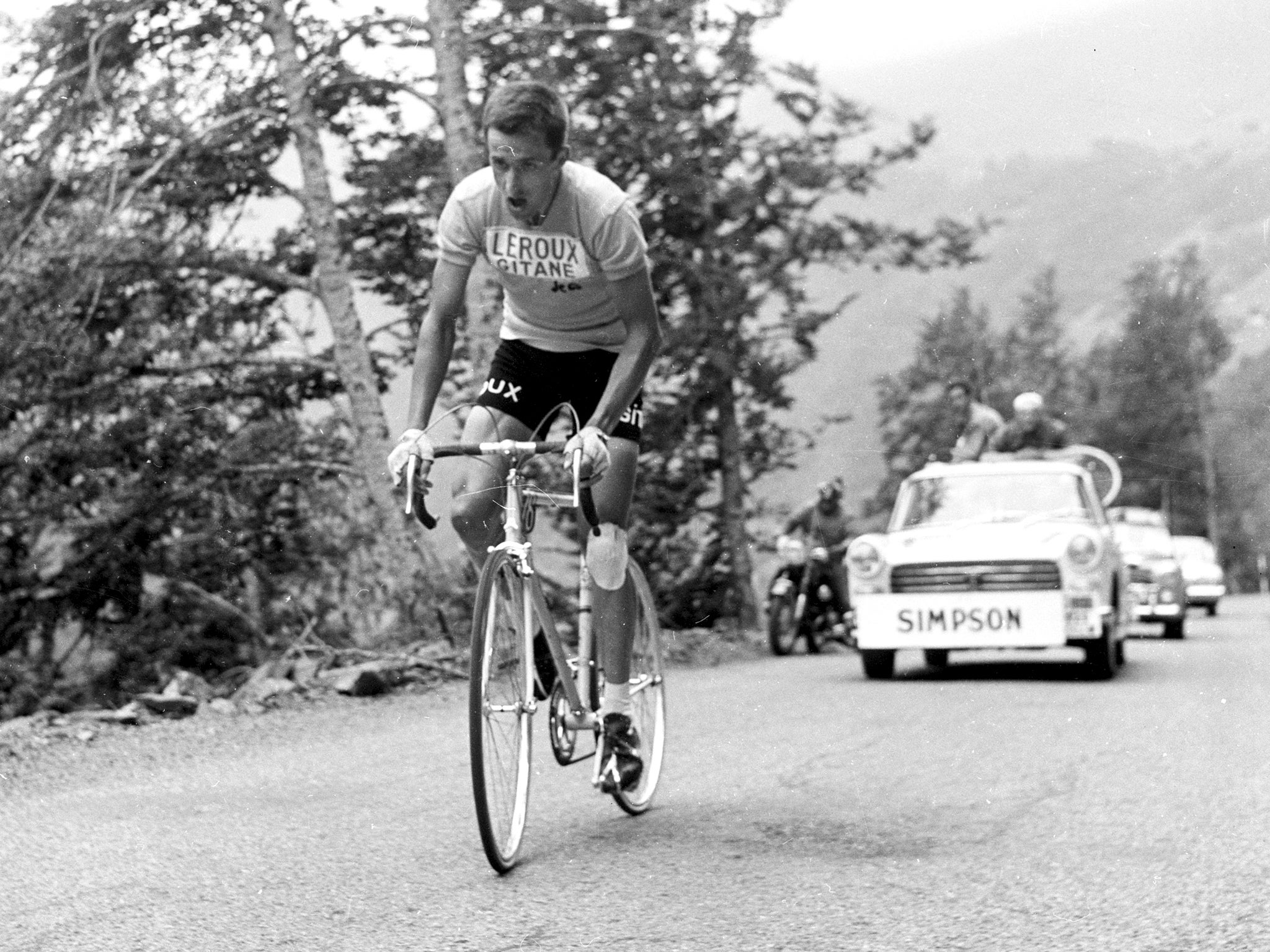

If the average British sports fan knows anything at all about Tom Simpson it’s that he died riding his bike. Ascending the notorious Mont Ventoux in the 1967 Tour de France, he collapsed. That year he was among the favourites for overall victory, the first Briton so heralded. But as the Tour entered its second week Simpson fell ill with diarrhoea. He laboured on. The 13th stage of the race, on 13 July, tackled the 1,909m peak of Ventoux. It was stiflingly hot.

Back in 1967 drugs were commonplace in professional cycling – only officially been banned on the Tour in 1965 – with amphetamine, known for its ability to allow athletes to push their bodies beyond normal limits, the medication of choice. The morning of Simpson’s death, Tour doctor and anti-drug campaigner, Pierre Dumas, had warned cyclists of the dangers of using amphetamine in the extreme heat. As the climb began Simpson fell away from the leading group. The footage of what then happened makes for painful viewing. He began riding erratically, his bike zig-zagging across the road. A kilometre from the summit he fell. His team and spectators rushed to help, suggesting he retire from the race. “Put me back on my bike,” Simpson insisted.

After another half kilometre, a group of spectators grabbed him to stop him from falling again. They carried him to the roadside, unconscious. The medical team gave him mouth-to-mouth and cardiac massage as Dumas arrived with oxygen. It was all too late. The autopsy discovered alcohol (courtesy of a slug of brandy at the foot of Ventoux) and amphetamine in his system and concluded he died of heart failure brought on by heat exhaustion, illness and drug abuse.

The maillot jaune – or yellow jersey – is, of course, one of the most emblematic items of sporting apparel. It is worn by the leader of the Tour de France and 10 years ago this month Bradley Wiggins rode into Paris wearing it as Britain’s first winner of the famous race, after taking the lead on stage 7 and holding it for 15 days, all the way to Paris. It was front-page news, the culmination of a great career on track and road. The average British sports fan knew all about it.

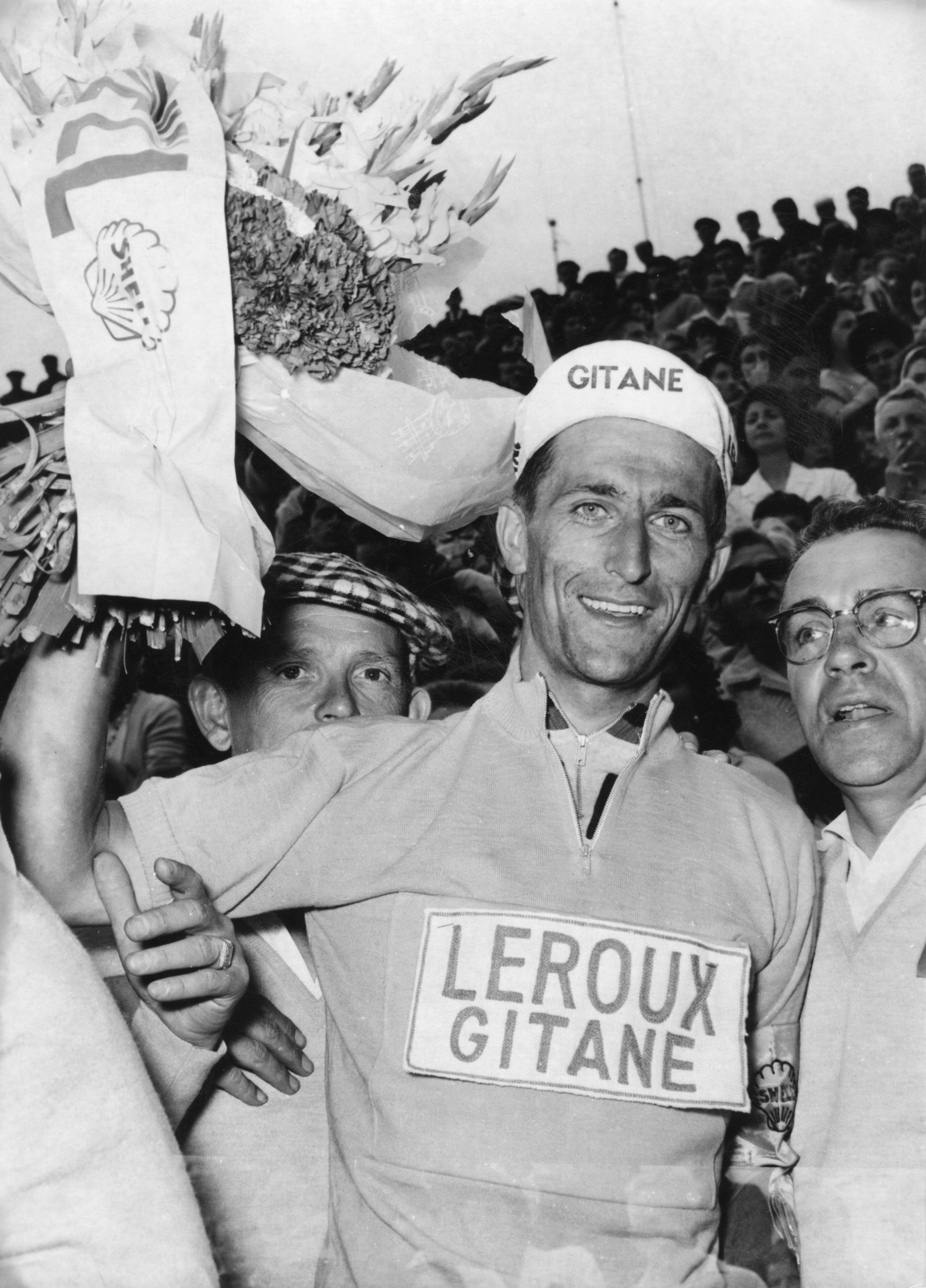

But the first Briton to wear that illustrious jersey was Simpson – exactly 50 years before Wiggins. Simpson pulled on the jersey for a single day after winning stage 12 from Pau to Saint-Gaudens in 1962. It was an achievement that went somewhat unnoticed in his home country whose sporting affections back then tended to be preoccupied by football, Ashes cricket, Wimbledon and the horses. Yet in the intervening five decades between Simpson and Wiggins, three Britons wore the yellow jersey with increasing levels of fanfare, mirroring the rise of interest in cycling and its consequent success in the velodrome and on the road. It’s been a slow but determined journey.

The stories of those pre-Wiggins wearers of yellow, and the other jersey colours available to riders on the Tour, are as diverse as the riders who have held them; a microcosm of British road cycling and the sport in general. While Simpson remains a fabled figure in British cycling it’s probably fair to say his achievements did not kick-start the huge fascination in the sport that we see in the UK today. His flame flickered briefly, brightly and was cruelly extinguished along with any wider public interest in competitive cycling he may have garnered. If they know anything else about Tom Simpson, that average British sports fan might recall he had won the BBC’s Sports Personality of the Year in 1965 after becoming Britain’s first professional road race world champion. The public loved a world champion but still knew little about the Tour de France.

If today’s boom in interest in competitive cycling had its big bang moment it wasn’t on the road with Tom Simpson back in the 1960s. In fact, it probably came on the track with Chris Boardman’s gold medal in the 4000m individual pursuit in the velodrome at the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona.

It was Britain’s first Olympic cycling gold since 1920 and it led to three decades of astonishing success in the Olympic velodrome making household names of the likes of Chris Hoy, Victoria Pendleton, Jason Kenny, Laura Trott and – before his road-racing days – Wiggins.

But despite his gold and subsequent world records on the track, it was arguably on the road where Boardman would make his mark, and – with the residual media attention following his Barcelona gold – finally pique British sporting interest in the Tour de France.

Two years after his Olympic success, and 32 years after Simpson first wore it – which is indicative of what an outlier the County Durham cyclist was – Liverpudlian Chris Boardman won the 1994 Tour prologue in Lille. Many, but not all, Tours start with a prologue to the first stage, a short, fast time trial intended to provide a yellow jersey wearer for the start of the race proper. Boardman’s track background meant he was ideally suited to the brief but sustained high-cadence riding of a prologue. When he took Olympic gold he actually caught and overtook ex-world champion Jens Lehmann in the final, something hitherto rarely seen.

Yates only held the jersey for one day. On the following day’s stage Danish rider Rolf Sorenson literally grabbed it, holding Yates back from contesting a sprint for time bonuses

Boardman’s GAN team had effectively signed him on the back of his Olympic success and three world-hour records for one reason alone – to grab the yellow jersey on that first, rapid sprint. And he delivered in the fastest speed ever seen at the Tour, becoming the second British wearer of yellow, which he surprisingly held for four days.

Boardman would go on to become known as Mr Prologue. He won the prologues of 1997 and 1998 (and finished second in 1996). He was the consummate professional, known as The Professor for his attention to detail and knowledge of bikes and cycling. “There’s never anything you do where you can’t think of a better way to do it,” he said. Old-school riders in the Tour peloton were frequently scornful of his meticulous preparation and track background, particularly French rider Luc Leblanc who had dismissively announced that half the peloton could beat Boardman. As he passed LeBlanc who had started a minute ahead of him in the 1994 prologue, Boardman smiled at him.

“Nice guy off the bike, assassin on it,” said his team manager at GAN Roger Legeay.

In that year of 1994, British yellow jerseys were like London buses. British cycling had waited more than three decades to see a rider in yellow but two rattled along in quick succession. No sooner had Boardman relinquished his yellow on stage 4 than along came Surrey-born Sean Yates who took the lead on stage 6. Yates was essentially a domestique, a rider who works for the benefit of his team leader rather than himself. Domestique translates into English as “servant” but on that day Yates was part of a breakaway group who built up such a sizeable lead that at its conclusion he had made up enough time to take the yellow jersey by a single second, the third Briton to do so.

Yates only held the jersey for one day. On the following day’s stage Danish rider Rolf Sorenson literally grabbed it, holding Yates back from contesting a sprint for time bonuses. Sorensen’s team-mate Johan Museeuw took the bonus and the race lead. It was controversial but road cycling is a cruel and duplicitous trade. “That sort of thing happened all the time,” said Yates afterwards. “I should have been ready for it.”

Yates, however, has cut a controversial figure. As a cyclist nicknamed “The Animal” he tested positive for anabolic steroids in 1989 but was cleared when a B sample failed to confirm the result. When he moved into team management he headed up Discovery, the team created by cycling’s most notorious drug cheat Lance Armstrong.

Yates insisted that in his six years with the team he was unaware of the drug programme that fuelled Armstrong’s now-deleted seven Tour victories but after moving on to become directeur sportif for British Team Sky that would deliver Bradley Wiggins’s 2012 triumph he left abruptly shortly after the Daily Telegraph reported he had admitted involvement in doping, contrary to Sky’s zero-tolerance stance. This was denied by Yates and Sky. Of Britain’s yellow-jersey wearer Yates was perhaps the most Marmite. “I know I’m pushing the boundaries. I know that one of these days I’m going to hit the dust and I’m going to be f***ing history, but sod it,” he declared of his attitude to the sport.

In between the yellows of Simpson and Boardman there had been individual stage victories for numerous British riders. Brian Robinson had won two stages in 1958 and 1959, but perhaps the most significant and certainly most underrated was another Yorkshireman, Barry Hoban. Although no Briton wore yellow between 1962 and 1994, sprinter Hoban straddled the gap with eight stage wins spread over eight years.

His first, however, was one he had no interest in winning. The peloton was hit hard by Simpson’s death. Dutch rider Jan Janssen who won the stage that day had no idea what had happened until later in the evening. “The atmosphere was terrible. He was so popular. It felt like it wasn’t true and I felt physically sick,” he said. The morning after there was talk about the Tour being cancelled, or at least that day’s stage. The riders held a two-minute silence and many were reluctant to start. Among those that did a pact was made – a British rider would be allowed to win the stage. That rider was Hoban. “It was no comfort, of course. It was all just horrendous,” he said. The connections between himself and his deceased compatriot run deep – in 1969 he married Simpson’s widow Daniella.

Hoban’s last stage victory arrived in 1975, and in terms of stage wins he is still the second most successful Briton to ride the Tour, albeit well behind Mark Cavendish’s international record-equalling total of 34.

There are, of course, other jerseys to be won on the Tour de France alongside the leader’s yellow. Red polka dots denote the leader of the King of the Mountains, the rider who accumulates the most points for leading over the Tour’s punishing summits. The first Briton to wear it was Robert Millar (now known as commentator and journalist Philippa York) in 1984. And not only did he wear it, but he also won the category overall, the first Briton to win any major Tour jersey.

Millar also finished fourth overall in that 1984 race, the highest position ever achieved by a British cyclist to that point, and also finished second overall twice in the Spanish Grand Tour, La Vuelta a España, and once on the Italian tour, the Giro d’Italia. All Millar’s successes went pretty much unnoticed in Britain where road cycling still had no widespread following. But in the context of their time, they were perhaps the greatest achievements by a British cyclist until the likes of Wiggins and Cavendish and their heirs such as Chris Froome and Tao Geoghegan Hart arrived in the 21st century. And all were achieved without the huge amounts of cash and research which has been pumped into British cycling over the past two decades.

The second Briton to wear the polka dot jersey was Millar’s Scottish compatriot and namesake David who wore it in 2007, but, unlike Robert, didn’t carry it all the way to Paris. David Millar is unique in being the only Briton to have held all four of the Tour’s jerseys: yellow, polka dot, white (for leading young rider) and green (the points – or sprinter’s – jersey).

In 2000 the Maltese-born Scot burst onto the scene by winning his very first Tour de France stage, a time-trial in Barcelona’s Futuroscope park (the Tour often starts outside its home country) meaning he was in yellow on his debut day. Because of his age that performance also put him simultaneously in the white jersey for leading young rider and also in green as the leader of the points competition. Although he never wore the last two that year because the yellow jersey takes precedence, he was still their custodian (and in 2002 he briefly held the white jersey once more, this time wearing it for three days). Boardman too had taken green but not white. And in 2007 in the early stages of the Tour, Millar led over the hills of Kent winning himself the polka dot jersey and becoming him the first Briton to hold all four.

But if Yates raised suspicions, David blew the myth of the honest British sportsman out of the water. In 2004 after French police had searched his flat and found drugs and syringes he admitted to a Parisian judge that he had used the red blood cell-boosting erythropoietin. There’s no denying doping was rife in that era, hidden behind the veil of omerta (or silence) that shrouded cyclists and teams, so perhaps Millar’s confession, after initially denying the charges, shouldn’t have been the surprise it was. “I was a nice guy, but I was a dick a lot of the time as well,” he says of himself.

The story goes that his father was so furious he punched him. He was stripped of his 2003 world time trial championship title, he lost his house, his job, his income and struggled with alcohol abuse. But unlike Armstrong or others of his era who argued that every rider was cheating so why shouldn’t they, David’s sense of shame ensured that he would – eventually – turn his conviction and two-year suspension into a positive. He is a staunch advocate today of racing clean, having inside knowledge of the circumstances that can turn athletes to drugs.

It’s like it has always been this way, with British sports fans expectant of victory rather than proffering ignorance and disinterest in what was once dismissively considered a ‘continental’ sport

As to the charge of hypocrisy, he says: “My epiphany came in a police cell. I’d come to hate cycling because I blamed it for the lie I was living. I don’t want anybody else to go through what I endured”. His 2011 autobiography, Racing Through the Dark, was lauded as “consummately told, frank in its admission of total culpability.” If redemption in the eyes of cycling fans wearied by endless revelations about their heroes doping their way to victory is ever possible, David has come closest to earning it.

Today David is one of the most articulate commentators of road cycling, a student of its history, and an intelligent voice on the issues it faces in a world where the scrutiny of social media is king. He now fronts ITV’s coverage of the Tour alongside lead commentator Ned Boulting. David’s ego, very much to the fore in his early career, is greatly diminished, allowing his undoubted intellect and empathy to become more prominent.

“People do make mistakes,” he admits. “And I think they should be punished. But they should be given the opportunity for a second chance. We are human beings.”

There would be one more jersey to be won before Bradley Wiggins secured everlasting fame as Britain’s first overall winner of the Tour. Mark Cavendish took the green jersey title in 2011, the immediate precursor to Britain’s astounding run of success that began with Wiggins.

It would have been a sporting travesty had the greatest road sprinter the world has ever seen – a record-equalling 34 Tour de France stage victories and counting – missed out on his speciality’s top accolade. But to win green in the Tour de France you have to reach Paris which means going over a lot of mountain tops to get there. Sprinters aren’t built for climbing and many of the world’s greatest never reach the French capital, most often failing to make the time cut at the end of the stage even if they make it up the mountain. But Cavendish played a canny game sticking with the large, slow-moving caravan of riders at the back of the mountain stages, knowing that if he did miss the time cut so would many others meaning the organisers would invoke the ruling that allows riders to continue in the race if too many disqualifications would decimate the field.

The Manx Missile was at the top of his game in 2011, also delivered to victory in the Road Race World Championship – the only Briton other than Simpson to take the title – by a strong British octet led by David Millar. More than any rider, Cavendish epitomised the forthcoming British dominance of the Tour de France.

Cavendish, an asthmatic, has endured many ups and downs in his professional and personal life. Entire chunks of seasons have been missed through injury or illness including mononucleosis, but still, Cavendish is hoping to break the record he jointly holds with five-time tour winner and all-time-great Eddy Merckx. However, it won’t be this year. Astonishingly, Cavendish has not been selected by his team Quick Step-Alpha Vinyl to go to the Tour in 2022 to defend his green jersey. After winning the British Road Championships this past weekend and a stage of this year’s Giro d’Italia in May, it seems an odd decision.

Whether or not he does eventually beat Merckx’s record, and despite the achievements of all those who followed him and despite him only holding the yellow jersey for one day in 2016, Mark Cavendish’s claim to be the greatest British Tour de France cyclist is indisputable – a claim backed up again in 2021 after returning to the tour at the age of 36 and once again taking home the Green jersey, 10 years after his first. “The Tour de France is ridiculously hard,” he says. “You get exhausted, in pain, and can be sick for days, but have to ride through it.”

And then came Wiggins, Britain’s first yellow jersey winner in the Tour’s 99th edition in 2012. His victory heralded a British run of success at the Tour, and in Europe’s other great stage road races, that could only have been dreamed about when Tom Simpson snatched yellow for a day back in 1962. Wiggins’s wingman in 2012 Chris Froome went on to even greater prestige, winning the Tour four times between 2013 and 2017. In 2015 he also took the King of the Mountains jersey too, the second Briton to do so after Robert Millar. He was followed by Geraint Thomas who won yellow in 2018.

The Giro d’Italia was won in 2018 by Froome and then two years later by the relatively unknown Londoner Tao Geoghegan Hart. Across the Mediterranean, Mancunian Simon Yates (no relation to Sean) won La Vuelta a España in 2018 succeeding, inevitably, Chris Froome, the winner the year before. And while organisers have often been criticised for an apparent lack of enthusiasm for the women’s version of the Tour and its on-off nature, Yorkshire’s Lizzie Deignan won La Course, as the women’s race was known until this year, in 2020.

It’s like it has always been this way, with British sports fans expectant of victory rather than proffering ignorance and disinterest in what was once dismissively considered a “continental” sport. Back in 1962 when Tom Simpson pulled on the yellow jersey his achievement went virtually unnoticed as, to a certain extent, did those of Boardman and Sean Yates. It seemed like a different era, and that’s because it was. Entirely different.

Simpson’s death on a barren mountain beneath a pitiless sun has passed into Tour legend. The spot where he fell is marked with an obelisk, a place of pilgrimage and warning. The rich history of Britons in the Tour began with Tom Simpson, the man who, quite wrongly, became famous for the way he died rather than the way he rode. Perhaps if he knew what would come years after him, he might have found some solace as glory, maybe, has eclipsed tragedy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments