Did the package holiday die with Thomas Cook?

Millions of people put their trust in Thomas Cook to deliver their dreams. But before we read the last rites on the package holiday business, Simon Calder considers how we got here

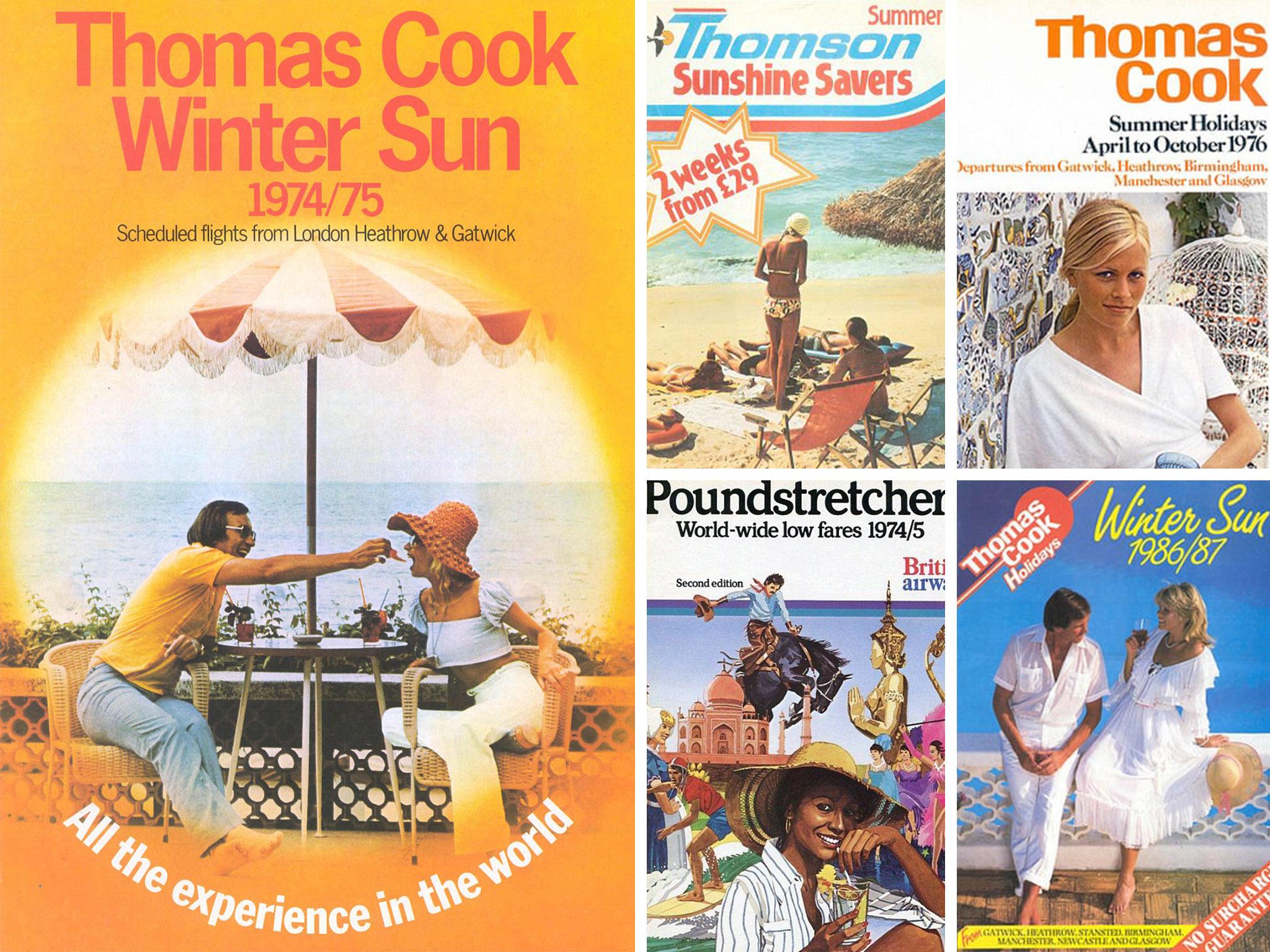

To make travel simple, easy and a pleasure” – that was the vision of Thomas Cook, who democratised leisure travel. The Methodist preacher from Derbyshire refused to accept the conventions and costs that restricted the horizons of working men and women. He industrialised travel, initially chartering an entire train in 1841 and selling each seat at an affordable price, and went on to establish a business that girdled the globe.

Cook’s main motivation was spiritual, not financial: he wanted people to experience the wonders of God’s world, and believed that mass tourism was a potential force for good to bring humanity together. And he understood the joy of discovering an exotic new destination (even though, for that pioneering trip, the train was bound no further than Loughborough). The company that bore his name became the most robust brand in travel, and hundreds of millions of holidaymakers put their trust in Thomas Cook to deliver their dreams.

And then, at 2am on Monday 23 September 2019, that 178-year mission ended. Nine thousand men and women lost their jobs when the UK tourism business folded. Close to one million customers had entrusted Thomas Cook with forward bookings, for holidays that now no longer existed. Hundreds of thousands of people are currently experiencing a facet of travel that is neither simple nor pleasurable: claiming back payments for future trips.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies