The Batman returns... and brings back memories of my childhood

With the newest Batman iteration about to hit cinemas, David Barnett looks back at his almost lifelong relationship with the Dark Knight

My very first piece of published journalism was about Batman. I was 19 and I wrote something for the Preston Other Paper, an independent magazine in Lancashire, when I was training to be a reporter on what was then Preston Polytechnic’s nine-month National Council for the Training of Journalists course for non-graduates.

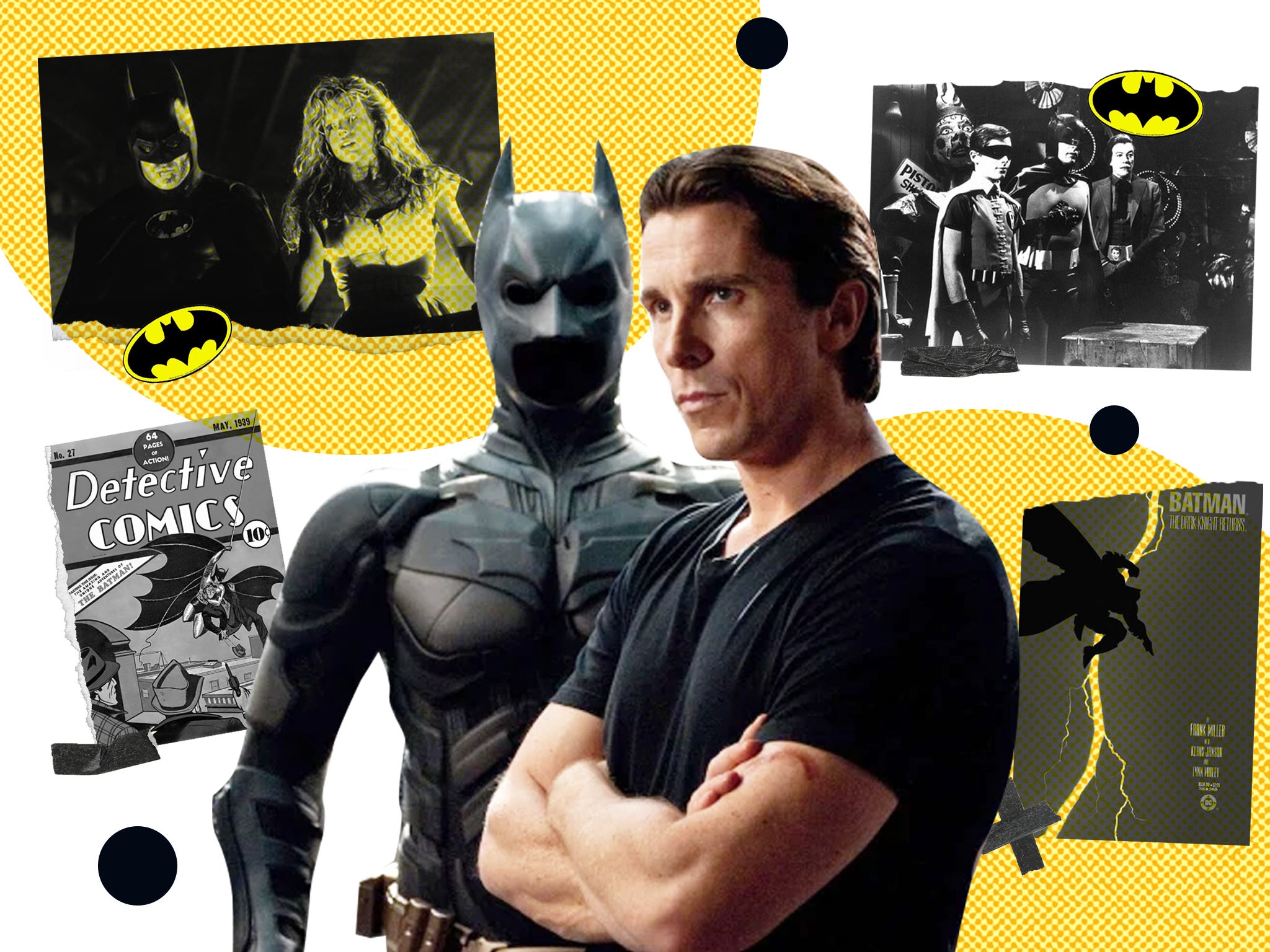

I wrote it ahead of the release of the 1989 movie of the same name directed by Tim Burton and starring Michael Keaton, Jack Nicholson and Kim Basinger. I didn’t get paid for it, but I was too young to care and too delighted to have been allowed to write about something I never thought I’d ever get the opportunity to do.

It perhaps seems strange now, when everyone and their mum knows Doctor Strange and the Eternals and Hawkeye and the Guardians of the Galaxy, but in 1989 a movie about superheroes was, for a geek like me, a seemingly impossible dream come true.

Superhero movies were just not a thing back then, In fact, before Tim Burton’s Batman in 1989, the previous Batman movie had been made almost a quarter of a century earlier, in 1966, a big-screen version of the popular TV series starring Adam West in the batsuit with Burt Ward as his palm-punching sidekick Robin. For people not familiar with the comics, that was the only Batman they knew, the Willy Wonka primary-coloured vision of a gaily-clad, crime-fighting duo facing off with explosive KERPOW! captioning against hammy villains and climbing up buildings that were actually flat on the floor, the camera tilted sideways to create the illusion.

However, if you were a reader of comic books, then you probably realised that the release of Batman in 1989 was capturing a growing zeitgeist that would take hold of popular culture like the Caped Crusader gripping the shirt of a two-bit hoodlum, and would still be holding on strong for three decades, leading up to the imminent release, on 3 March, of the latest chapter in the hero’s cinematic saga, The Batman, starring Robert Pattinson under the hood.

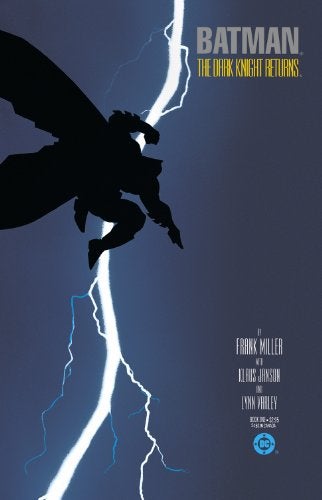

That’s because a couple of years earlier, Batman’s publisher DC released a comic that was not only like nothing anyone had seen before in terms of the actual, physical look of it and what it did with the beloved character of Batman, it would help to revolutionise the entire comic book industry.

It was called The Dark Knight Returns and it was written by Frank Miller, with art by Miller and Klaus Jansen. Unlike the usual flimsy comics that were published every month on cheap newsprint, it was presented on glossy paper with card covers, more like a book than anything.

And the Batman it showcased was a far cry from the camp goofiness of the Sixties TV series. It posited a 55-year-old Batman coming out of retirement to fight rising street crime and authoritarian corruption in a dystopian vision of Batman’s fictional stomping ground of Gotham City. It was dark, violent and morally ambiguous, and it not only ushered in a new era of mainstream comics that were no longer aimed at children, but helped to popularise a revitalised label for this sort of thing… one that, although coined in the 1960s, hadn’t had much traction until two decades later: the graphic novel.

But who is the Batman?

Thanks to the success of Batman in 1989, the character has been firmly fixed in the pop cultural psyche, and next month’s The Batman will be the eighth movie since Tim Burton’s revitalisation, alongside a slew of animated movies and Batman’s appearances in DC’s Extended Universe movies such as Justice League and Suicide Squad.

I don’t remember when I first encountered Batman. In fact, I don’t really recall a time when I didn’t know Batman

So you know who Batman is. He’s Bruce Wayne, only son of rich businessman Thomas and his wife Martha. As a child, Bruce watches his parents gunned down by a mugger when they – rather inadvisedly – take a shortcut after a trip to the cinema along Crime Alley.

Orphaned Bruce is put in the care of the family’s redoubtable butler, Alfred, and thanks to the cushion of the inherited family fortune is able to devote his growing years to training his mind and body to almost superhuman levels. He broods on the killings of his parents and decides to do something about it. But by now Bruce is a millionaire playboy, and can’t exactly just go out fighting crime. Pondering in the gothic pile of Wayne Manor one night, he muses: “Criminals are a superstitious cowardly lot, so my disguise must be able to strike terror into their hearts. I must be a creature of the night, black, terrible, a… a…” And, right on cue, a bat flies in through the window, and a star is born.

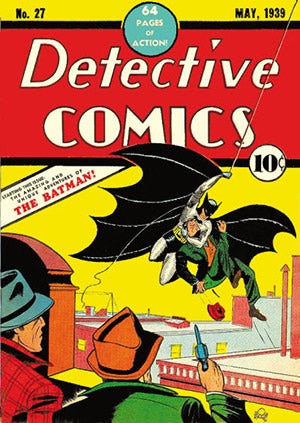

Batman first appeared in the 27th issue of Detective Comics, published in May 1939 by National Comics, the forerunner of DC Comics. Detective Comics was an anthology title featuring mainly hardboiled crime stories. The company had debuted Superman earlier that year, and wanted more of these costumed crimefighter characters. Bob Kane, along with Bill Finger, was tasked with creating Batman, and they drew on a number of sources, including the 1930s pulp heroes such as Doc Savage and the Shadow, Sherlock Holmes’s sleuthing skills, and even Leonardo da Vinci’s early helicopter designs, to create the look and idea of a masked, caped, detective who prowled the night.

I don’t remember when I first encountered Batman. In fact, I don’t really recall a time when I didn’t know Batman. Buying American comics in the UK in the 1970s and 1980s was always a hit-and-miss affair. Newsagents would get random selections of DC and Marvel issues, and there was no guarantee they’d get the next numbered edition in the following month. So UK readers of American comics built up fractured, uneven collections, often dropping in at the middle of an ongoing story and never finding out what happened after the cliffhanger ending.

And Batman in particular seemed to have many different incarnations over that period. The Batman of the 1960s had often mirrored the campy TV show, with the accent on the weird and wonderful things the Caped Crusader could summon from his utility belt, such as shark repellant and zip wires. In the 1970s he took a darker tone, hugging the shadows more, his cape like a vampire’s cloak, the ears on his cowl elongated and sinister.

Some things remained fairly constant, to varying degrees. Bruce Wayne used his fortune to build a fleet of high-tech vehicles, including the Batmobile and a variety of airborne and marine transports. He had a Batcave, from where he did his detective work, and it had a Trophy Room, stuffed with giant pennies and robotic dinosaurs from his adventures. There was a parade of regular villains such as the Joker, Catwoman, the Penguin, the Riddler. Commissioner Gordon summoned Batman with a bat-signal that projected the famous bat symbol on the smoggy, low-lying clouds above Gotham. And, rather incongruously for a vigilante loner, he was often seen adventuring with his super-powered colleagues in the Justice League of America.

At some point in my early teens, in the first quarter of the 1980s, my comic reading dropped off. Puberty intervened and I discovered music, casual sportswear, and girls (though girls didn’t discover me). I remember the moment vividly that I stopped reading comics: I was in a newsagents when a small group of girls from my comprehensive school walked in. I looked down at the five or six Marvel and DC comics I’d found on the shelf. And suddenly I felt odd and out of place. I was at the till and quickly bought a copy of The Sun newspaper, shoved my comics inside, and walked out.

Batman, I let you down. I denied you. I’m sorry. But it was a different world, back then. In the working class north of 1983, I ached to fit in, and not be an outsider, a weirdo. Reading comics was considered childish and strange and I didn’t want to be seen as any of those things.

There was a precedent for this feeling, I suppose. Perhaps I was channelling a pop cultural genetic memory from the 1950s, when comics were not only seen as odd and weird and childish, but also very, very dangerous. And none more than Batman.

In 1954 a child psychologist called Dr Frederic Wertham published a book called Seduction of the Innocent, in which he claimed the comics of the time were having a detrimental effect on the collective psyche of American children.

Most of his ire was directed at the horror and crime comics – which were admittedly lurid, violent and gory – but he had quite a lot to say about superheroes, especially Batman and his sidekick Robin, aka Dick Grayson, the young orphan he took in and trained to be a crimefighter too.

Basically, Wertham thought the relationship between the two (Dick Grayson was termed as Bruce Wayne’s “ward”) was highly irregular and unhealthy.

He wrote: “Only someone ignorant of the fundamentals of psychiatry and the psychopathology of sex can fail to realise a subtle atmosphere of homoeroticism which pervades the adventures of the mature Batman and his young friend Robin … Sometimes Batman ends up in bed injured and young Robin is shown sitting next to him. At home they lead an idyllic life. They are Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson. Bruce Wayne is described as a ‘socialite’ and the official explanation is that Dick is Bruce’s ward. They live in sumptuous quarters, with beautiful flowers in large vases, and have a butler, Alfred. Batman is sometimes shown in a dressing gown… it is like a wish-dream of two homosexuals living together.”

Seduction of the Innocent became a national bestseller, and prompted a witch hunt against comic books. This was the 1950s, and America was on a hair-trigger about pretty much anything – communists, civil rights, women’s liberation, beatniks… anything that didn’t fit the vision of the post-war, “Hi honey, I’m home!” utopia they were trying to build.

Pattinson has signed on for three films, directed by Matt Reeves. Does the world need yet another Batman on screen? It seems we do

The public had a new folk devil to vilify, the government got involved, and after Wertham gave evidence at a Senate committee to look into his findings, the comics industry was given an ultimatum by the state: clean yourself up or we’ll do it for you.

The introduction of a self-regulating Comics Code Authority sanitised comics and essentially killed off most of the horror and crime titles, but superheroes – and Batman – survived, despite Wertham’s best efforts.

I never properly abandoned comics, not really, but I pursued them more quietly. To be honest, I was always more of a Marvel kid than DC. Marvel comics seemed to be more widely available, and there were British black-and-white reprints of them, whereas DC never seemed to gain that traction in the UK. Also, DC’s characters such as Batman, Superman and Wonder Woman had all been published in isolation at first, only later being drawn into a cohesive universe. When Marvel began in the 1960s, it was all connected from the word go.

Also, Marvel characters seemed more relatable. Spider-Man was Peter Parker, a kid from a working class background who did well at school, like me. He was granted his powers through sheer accident. That could happen to me, I reasoned. But I could never be Batman. My parents were far from rich, and even if they were killed by a mugger when I was small I wouldn’t have a personal fortune, an Alfred, a manor and a Batcave with which to wage my war on crime.

As I got older, all those things about Batman began to sit uncomfortably with me. He was rich beyond the dreams of avarice. He seemed to split his time between running his father’s business and partying with supermodels. And yet, at night, he would put on his skin-tight suit and wear a mask and go out beating the crap out of some disadvantaged kids who were nicking a TV from a shop. Imagine if Elon Musk were doing that today.

But my proper return to comics in the mid-to-late Eighties coincided with a revolution in the form. Alan Moore’s Watchmen and the aforementioned Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns were re-drawing the superhero legend in much blacker, morally ambiguous tones. Batman seemed especially ripe for reinvention. Alan Moore, with artist Brian Bolland, cemented Batman’s flip-side relationship with his long-running antagonist the Joker in the graphic novel The Killing Joke in 1988, while writer Grant Morrison and artist Dave McKean explored Batman’s own personal psychology in Arkham Asylum the following year. Comics were no longer just for kids. And that led to the release of Tim Burton’s Batman.

If I thought I was the only person who would go watching it, if I imagined only me had kept the flame burning and loved Batman during those 20-odd years when he’d never graced the cinema screens, I was wrong. Watching Batman in 1989 was the first time I had ever seen people stand up and cheer a movie at the end.

Three sort-of sequels followed in the 1990s; I say sort of because they had different directors and actors (Michael Keaton in Batman and Batman Returns, then Val Kilmer in Batman Forever, finally George Clooney in Batman and Robin). The quality varied wildly, and after flirting with the brooding, dark Batman of the then-current comics the franchise tried also to accommodate the campiness of the 1960s, with grotesque portrayals of the villains and an over-exaggerated Gotham, leading to unsatisfying results.

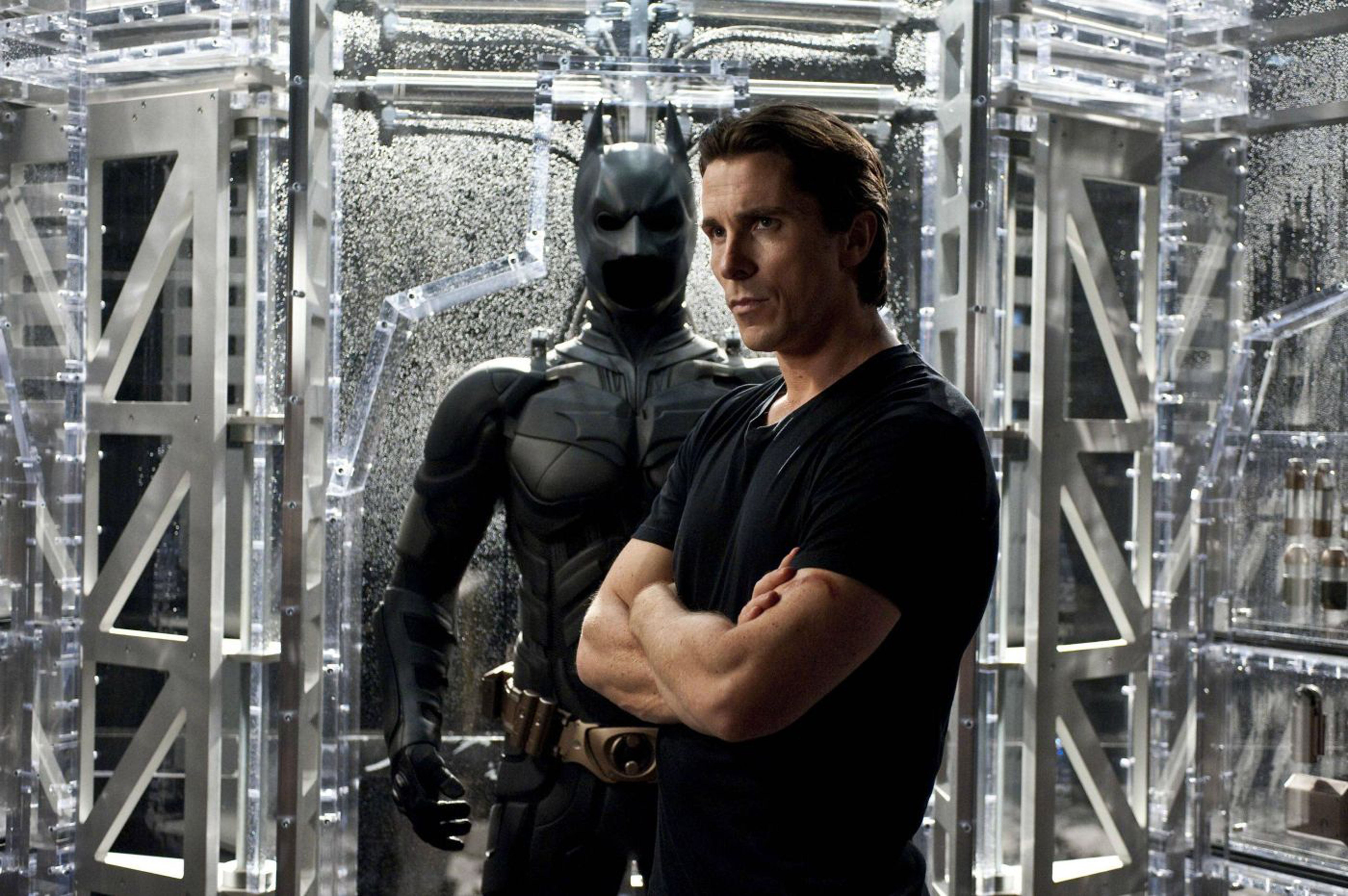

The most critically acclaimed version of Batman on screen has to be Christian Bale’s portrayal in Christopher Nolan’s trilogy Batman Begins, The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises, between 2005-12. These transplanted Batman into a grimy and often bleak real-world setting, as near as they could, with a lot of success. But, it has to be said, not a lot of fun.

That perhaps came with the creation of the DC Extended Universe, an attempt to mirror Marvel’s cinematic juggernaut, with the Superman movies and then in 2016, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, which led directly to the Justice League ensemble movie the following year.

It’s testimony to Batman’s staying power that he got top billing in the 2016 film, despite Superman having had more recent cinematic outings. And that movie did draw on the rivalry between the two heroes from Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns comics especially. But still; Ben Affleck’s performance didn’t quite hit the spot for a lot of people. Which is why, this year, we’re getting yet another big screen Batman.

The addition of the word “The” before Robert Pattinson’s Batman gives those in the know an indication that this is not going to be fun. Batman is the brightly-coloured guy who trades puns and kerpow punches with pop-art villains. The Batman is the dark, psychotic, vigilante who prowls the night and beats the living crap out of people.

Pattinson has signed on for three films, directed by Matt Reeves. Does the world need yet another Batman on screen? It seems we do. And will this be the portrayal that finally hits all the right notes, satisfying a mainstream cinema audience while serving the comic book fans, just as the Marvel movies seem to have achieved? Will we get the Batman we deserve?

In the manner of Commissioner Jim Gordon, long-suffering boss of Gotham City’s embattled police department, let’s go up to the roof, switch on the bat-signal, and see just who comes swooping out of the night this time.

The Batman is in cinemas from 4 March.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments