Sting, Shakti and sex: The exhibition changing our understanding of tantra

When you hear ‘tantra’, you probably think of sex... or Sting. But, as Harriet Marsden discovers at the first exhibition to trace its 1,500-year history, the practice is more of a radical philosophy than a wellness trend

A woman has her legs slung over the shoulders of a man, bent backwards like a stone comma. One of her feet is on the man’s headdress, while he rests his chin on her “yoni”. I’m hunkered down on my knees in a back room of the British Museum, staring at a carved depiction of oral sex. Not your typical Tuesday.

My guide tells me that the statue is 11th century, possibly from the Elephanta cave temples near Mumbai, and came to the museum in 1865. It venerates the vulva, or the source of creation, she explains, even though oral sex was considered transgressive at the time. On the other side of the sculpture, a woman stands between two men, one impressive “lingam” held between her breasts.

The carving is called “erotic maithuna”, a Sanskrit term often translated as sexual union. It is just one of the items that will be on display in the museum’s upcoming tantra exhibition. I’m getting a sneak preview of “Tantra: enlightenment to revolution”, which opens on 23 April. It promises to be the first exhibition to look at the whole history of tantra, from ancient inception to impact on global modern culture.

When you hear “tantra” in the UK, you probably think of sex – and Sting. The Police musician famously revealed, in an unforgettable interview with Q magazine alongside Bob Geldof in 1993, that he was a fan of tantric yoga and sex. “It can go on for five hours,” he bragged.

(He backtracked in 2013, claiming he was drunk and winding up Geldof. Surely nothing whatsoever to do with the dismissal of his tall tales by his second wife Trudie Styler in 2011. “Suddenly I was doing it all day long,” she said. “Well, if only.” Sadly, we’ll never find out whether he could perform cunnilingus for five hours because he declined to be interviewed for this piece.)

The exhibition is aiming to recontextualise tantra – and re-educate its audience. The brains behind the outfit – and my guide – is Dr Imma Ramos, a glamorous 31-year-old in a Massimo Dutti jacket. “The key thing about tantra as a philosophy,” she explains, “is that it teaches that the material world itself is a manifestation of Shakti: the divine feminine power.”

When the sculpture arrived, it was put in the mysterious secret section of the British museum – the Museum Secretum. At the height of the Victorian period, curators took objects deemed obscene or erotic and hid them away. Only gentlemen, well educated and scholarly, could enter – no women or working classes. The statue, depicting oral sex – not the marital, reproductive purpose of sex – was hidden away until the 1960s free love movement.

It’s somewhat ironic that a belief so deeply rooted in feminine power has become known for Sting’s false braggadocio, and that a sculpture depicting female pleasure could only be viewed by men.

Tantra might be everywhere in Asian cultural and religious traditions, but it is largely misunderstood in the west. Tantra – like many eastern practices – has been somewhat co-opted by the “wellness” industry. You might have unknowingly come across it in your hatha yoga class, or tried your hand at tantric massage. And who can forget that scene in Sex and the City, when the women attend a tantric “lingam massage” seminar and a pensioner accidentally ejaculates on Miranda’s hair?

People often ask me, the tantra show, is that like the Kama Sutra? I have to explain that tantric sexual rites are not about the pursuit of pleasure for its own sake: it’s about the reconciliation of opposites and the union with divinity.

But Dr Ramos is on a mission. A specialist in south Asian art and the mingling of sacred and political in visual culture, she joined the British Museum five years ago and proposed the idea of a big tantra project – but as a book. “When I started at the museum, I was really amazed by the breadth of the south Asian collection,” she tells The Independent, “and also by the nature of the tantric material that we had in storage.”

The British Museum is home to one of the world’s largest collections of tantric material, more than 100 sculptures, paintings and prints will star in the exhibition, including some of the oldest tantras in existence. Dr Ramos planned to write a book about the museum’s collection, but the exhibitions department immediately recognised a good idea. The book, a product of her many years of research on tantric visual culture, is accompanying the exhibition, along with loans from institutions around the world.

She says: “I think people were really curious and excited about it because they knew it would capture the public’s imagination, because there are certain preconceptions about what tantra is, so they knew the term itself would attract attention. They thought it would be really interesting to challenge those preconceptions, through the exhibition narrative.”

There is no age restriction on the exhibition – although there will be a warning about material of a sexual nature. But there is also a label explaining that much of the material has been misinterpreted.

The lead supporter of the exhibition, the Bagri Foundation, showcases artists and experts from Asia through a seemingly endless array of programmes of film, art, music, dance, literature, courses and lectures. A trustee of the foundation, Dr Alka Bagri, says: “We are excited to be part of an exhibition that we hope can change people’s perceptions of tantric philosophy and its art, contributing to a greater understanding of this complex subject.”

Dr Hartwig Fischer, the director of the British Museum, says: “Tantra has been the subject of great fascination for centuries and continues to capture people’s imaginations. We’re delighted to present the first historical exploration of tantric visual culture from its origins in India to its reimagining in the west – where visitors will be able to explore the wider philosophies of tantra.”

Tantra, from the Sanskrit tan (to weave or compose), is a set of beliefs that emerged in India around AD500, alongside Buddhism and Hinduism. It is based on sacred instructional texts, or tantras, which are often written as a dialogue between god or goddess, explaining how to invoke one of the many tantric deities. The purpose is to achieve liberation and unity. But more than a religious rite, tantra is a radical philosophy. The rituals transgress social and religious boundaries, and especially challenge gender norms.

In a way [tantra] goes against so much of historical and current messaging about sex which is goal-orientated and focused, whereas tantra is about fully engaging with the pleasure of an experience, whether it’s a solo or partnered practice

In tantric sex, the woman assumes the most important role, because she is an embodiment of Shakti. “This affirmation of the feminine was very radical at the time, because earlier Hindu and Buddhist traditions taught that the female body was actually an impediment to achieving enlightenment.”

The veneration of Shakti, the divine feminine, gave birth to the rise of goddess worship across south Asia. Women played powerful roles within tantric practice: as gurus, or teachers, because they were embodiments of Shakti. Gender, in the form of female tantric gurus, is a focus of the exhibition. Not loving mothers, docile daughters or submissive wives – the women I’m seeing are powerful and terrifying.

We look at a Tibetan prayer mat, depicting a red goddess from behind, with one leg wrapped around a god mid-coitus. The god represents compassion, while the goddess represents wisdom, I’m told. Surprisingly, it would have been used in a monastery for meditation purposes. It begs the question: how did celibate monks and nuns relate to this very sexual image? The key is symbolism: they imagined the sexual union as a union of the deities in their own bodies.

They might be mid-coitus, but the god and goddess are also carrying weapons – knives, nooses, meat cleavers. There are fangs, and garlands of decapitated human heads, symbols of the ego. There is even a cup of human skulls. The interplay of erotic and violent iconography is everywhere in the exhibit – and is unique to tantra.

We look at an 18th century courtly painting showing female gurus offering tantric initiation, and small statues of gurus, with deliberately demonic faces. One of the women depicted, an early tantric master, supposedly asked Shiva to take away her beauty to give her a more transgressive appearance, in the style of representations of tantric goddesses like Kali.

The exhibition will also feature contemporary works, including Sutapa Biswas’s 1985 work, Housewives with Steak-Knives, which shows Kali imagined as a feminist icon. She has a demonic expression, and is holding a machete above her head menacingly, with bloodied hands and a necklace of decapitated heads. One of them is clearly Hitler.

By its nature, tantra is rebellious. During the Indian fight for independence in the late 19th century, tantra became a tool of the revolutionaries, particularly in Bengal, who reimagined the goddess Kali as a symbol of insurgency against the colonial British. Many of the depictions show Kali wearing necklaces of decapitated British heads.

I was totally ‘stuck in my head’, which is something I still struggle with as attraction and closeness with a person is massively based on intellect and cerebral connection

Some of those tantric texts contained passages that were “sexual in nature” – although only a small proportion. But when texts were first translated into English, they were effortlessly misunderstood. Translators failed to recognise that those erotic descriptions could be read as symbolic.

To be fair, one of the first scholars to seriously study tantra, John Woodroffe, a British orientalist known by his pseudonym Arthur Avalon, tried to defend it and present it as a philosophical system rather than sexual practice. But the damage was done.

Dr Ramos puts it: “The Brits sort of read it all literally and also simultaneously completely misunderstood the passages as well.” The Americans are also guilty – one in particular: pioneering yogi and businessman Pierre Bernard, credited with introducing tantra to the US and misrepresenting it as sexual.

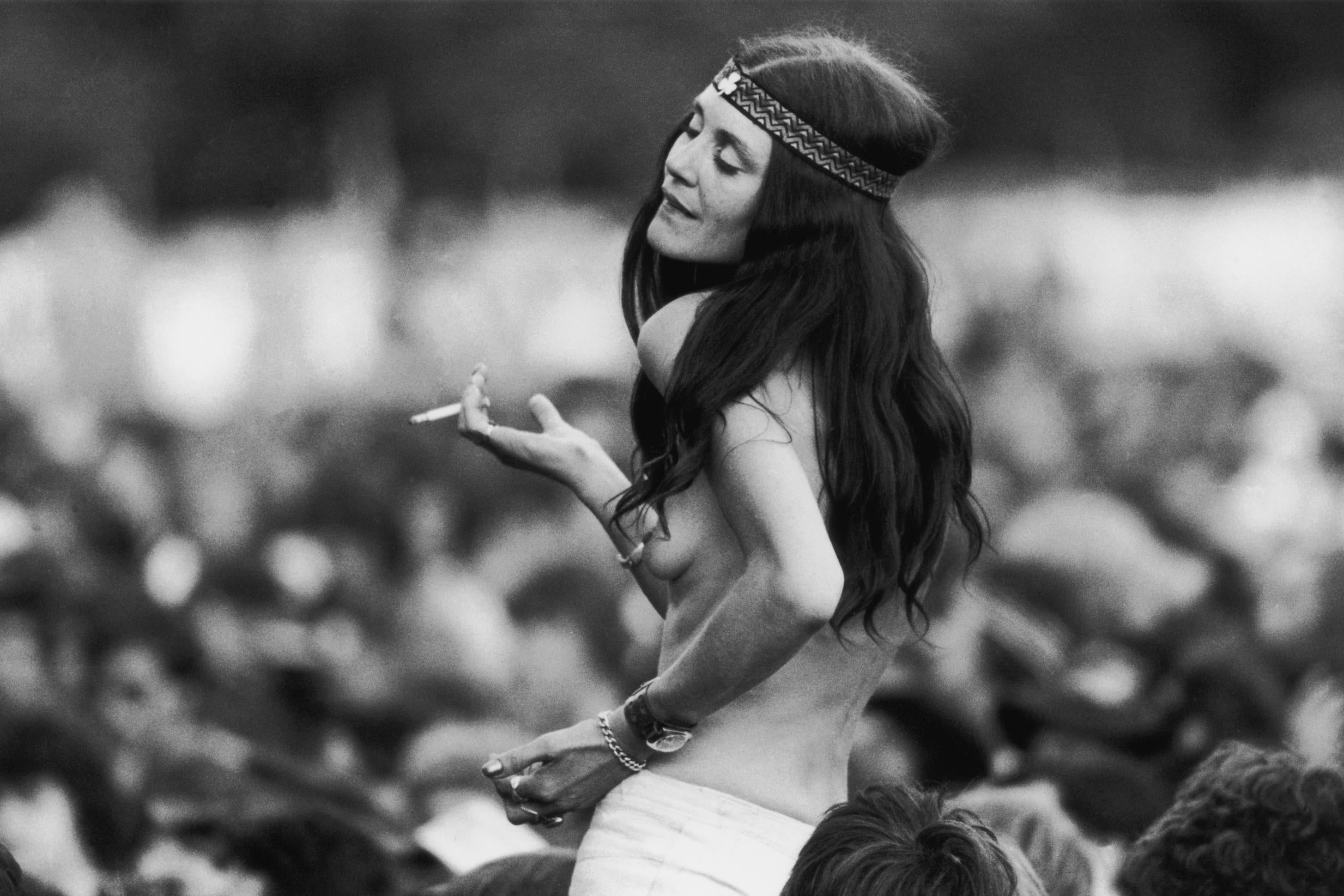

Tantra would go through another rebirth, exploding onto western consciousness in 1960s hippy subculture, seen as an anti-capitalist movement that promoted free love. Psychedelic posters with tantric symbolism were plastered all over London and San Francisco, and had a major impact on the zeitgeist. The exhibition features one of the earliest ecological protest posters, crying: “Save us now!”

The first major exhibition about tantra took place in London, at the Hayward Gallery in 1971: “Tantra, the Indian cult of ecstasy.” Tens of thousands flocked to see the statues and objects, as well as the paintings of couples in flagrante delicto. But the way it was advertised created an idea that tantra was some sort of cult that could challenge stifled attitudes towards sexuality. “In a way,” says Dr Ramos, “this exhibition now is a response to that one in 1971.”

“The idea is that the couple assume the roles of deities, so in the Hindu context, this might be Shiva and Shakti, for example. And one of the central aims of tantric sexual rites was to unite with divinity, and attain enlightenment, rather than pleasure for pleasure’s sake like the Kama Sutra.”

Kama, one of the four key goals of life according to Hinduism, is basically pleasure or desire. And the Kama Sutra, like tantra, is only partly about sex. As a whole, it’s a 2,000-year-old courtly instruction manual for a happy marriage and a virtuous way of life. Like tantra, women are a big focus. But the point of tantra is not desire, or the pursuit of pleasure for its own sake: rather to transcend desire.

Implosive orgasms help to clear the system and the sexual energy is used within the body as a part of healing and connection. Therefore, tantric sex helps us to get clearer – our body is a vessel and it helps us to clear the energy centres

Of course, that might have some desirable side effects. Iain* was 35 when he went for his first tantric massage – and experienced his first orgasm. “I was carrying a lot of trauma and emotional pain,” he says, “and I was really broken down and anxiety-ridden.”

Iain had suffered a breakdown in 2005, leaving his job in London to move back in with his mother. Six months later, she married a man who would turn out to be an abusive, violent bully. Caring for her through the breakdown of the marriage, the domestic violence court case and, finally, her diagnosis with dementia, took its toll. “I was totally ‘stuck in my head’,” he explains, “which is something I still struggle with as attraction and closeness with a person is massively based on intellect and cerebral connection.”

Iain had only had one relationship with a woman before. He had also never been able to masturbate. “Perhaps this had something to do with why I was so stuck, or unexplored, as a man,” he says.

There is no official definition of tantra, so anyone can market themselves as a practitioner. Iain says he knows of a tantra retreat run by a man who abuses that position, and sexually exploits the women. The line between consensual tantric practice and transactional sex, or prostitution, can also become blurred.

Iain began to explore a website called FBSM – the Full Body Sensual Massage Forum And Therapists Directory. And in 2017, Iain went to visit “Goddess Maggie*”, in an elegant white building in Paddington.

Maggie, in her mid-twenties, was wearing “elegant red knickers, bra and matching red heels”. A short hallway led to a tiny bathroom and kitchen, which had been turned into the therapists’ private area secluded by panelled room dividers. A massage table with a hole at one end stood in the centre, with a sofa and, behind more panelled blinds, a low bed covered with a plain white sheet.

Iain found Maggie very easy to talk to, and felt a genuine rapport. He took a shower before walking towards the bed. Maggie was “butt naked” when she began to massage him. But although Iain was “in the moment”, he did not have an erection. He needed the affection, he says, that just wasn’t present in a transactional arrangement. It would take another four sessions before he finally ejaculated. “It was a watershed moment,” he says, “and I could finally manage to do it myself in my own time.”

Michael Charming – real name – has been a self-defined tantra practitioner and orgasm coach for five years. He says: “We are familiar with orgasm, but tantra reshifts the whole paradigm from external to internal – this is known as an ‘implosive orgasm’. Implosive orgasms help to clear the system and the sexual energy is used within the body as a part of healing and connection. Therefore, tantric sex helps us to get clearer – our body is a vessel and it helps us to clear the energy centres.”

Charming, who grew up in India, is also the founder of something called the “Amplified Orgasmic Method”. That’s more or less what it says on the tin: how to have more and better orgasms. He tells me that his sex “is no longer a quick 30 minutes” but lasts “for hours and hours”.

Iain continued to visit Maggie, he estimates between 10 and 15 times, over the next year and a half. He believes that opening himself up to tantra helped him “unlock” and face the hurt he was carrying. “I’m not saying it’s a magical key, but it may lead the individual to insight on their feelings and interactions and relationships with people.”

Kate Moyle is a sex expert for LELO, a Swedish “intimate lifestyle” company specialising in upmarket sex toys and massage products. She tells The Independent that tantra is about “going beyond”, bringing together parts of the self “in a way of ‘wholeness’ or ‘oneness’ which can intensify or deepen whatever experience we are having, not just necessarily sexual ones”.

She explains that tantra is about embracing the sensuality of an experience – the the body, the breath and the power of intimacy. “In a way it goes against so much of historical and current messaging about sex which is goal-orientated and focused, whereas tantra is about fully engaging with the pleasure of an experience, whether it’s a solo or partnered practice.”

Ultimately, Dr Ramos says, tantra is about the reconciliation of opposites: sacred versus profane, the self versus divine, pure versus impure, masculine versus feminine. “It’s about seeing the world, clearly as it actually is.”

‘Tantra: enlightenment to revolution’, supported by the Bagri Foundation, opens at the British Museum on 23 April 2020

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments