The epic life and mysterious death of Lord Ted Deerhurst

The English viscount turned his back on green pastures for a surfboard and Hawaiian waves. But his untimely death at 40 shocked his family. In the first of a two-part exclusive, Andy Martin, friend and fellow surfer, sets off to see if he can find out what had happened to the golden boy of North Shore

I met Ted for the first time in the summer of 1989 on the south-west coast of France. I was a surfing correspondent and he was a would-be world surfing champion. Lacanau, colonised by Quiksilver, populated by marquees and stages and pennants and music, had the feel of some medieval jousting tournament. Ted – Edward George William Omar Deerhurst, Viscount – riding a board with the distinctive Excalibur design, his trusty sword carving through the surf, long blond locks glinting in the sun like a radiant helmet, fitted right in there. He was like a knight errant on a quest for the elusive holy grail.

A former amateur who had represented Great Britain in South Africa, he was in search of points to climb up the ASP (Association of Surfing Professionals) ladder. It had been a bit of a struggle hitherto, over a number of years, but he was hopeful that this summer would be the breakthrough for him. He struck a brave, optimistic note. Mingled with a degree of melancholy yearning.

But there was one other British surfer who was competing in the French Triple Crown. His name was Martin Potter, aka “Pottz”. He was semi-invincible. Pottz won at Biarritz, scooped the Triple Crown, and was in pole position to take the world title, thus becoming my passport to the giant waves of Hawaii. But I was rooting for the underdog, the longshot, the loner, the unsung hero. Ted.

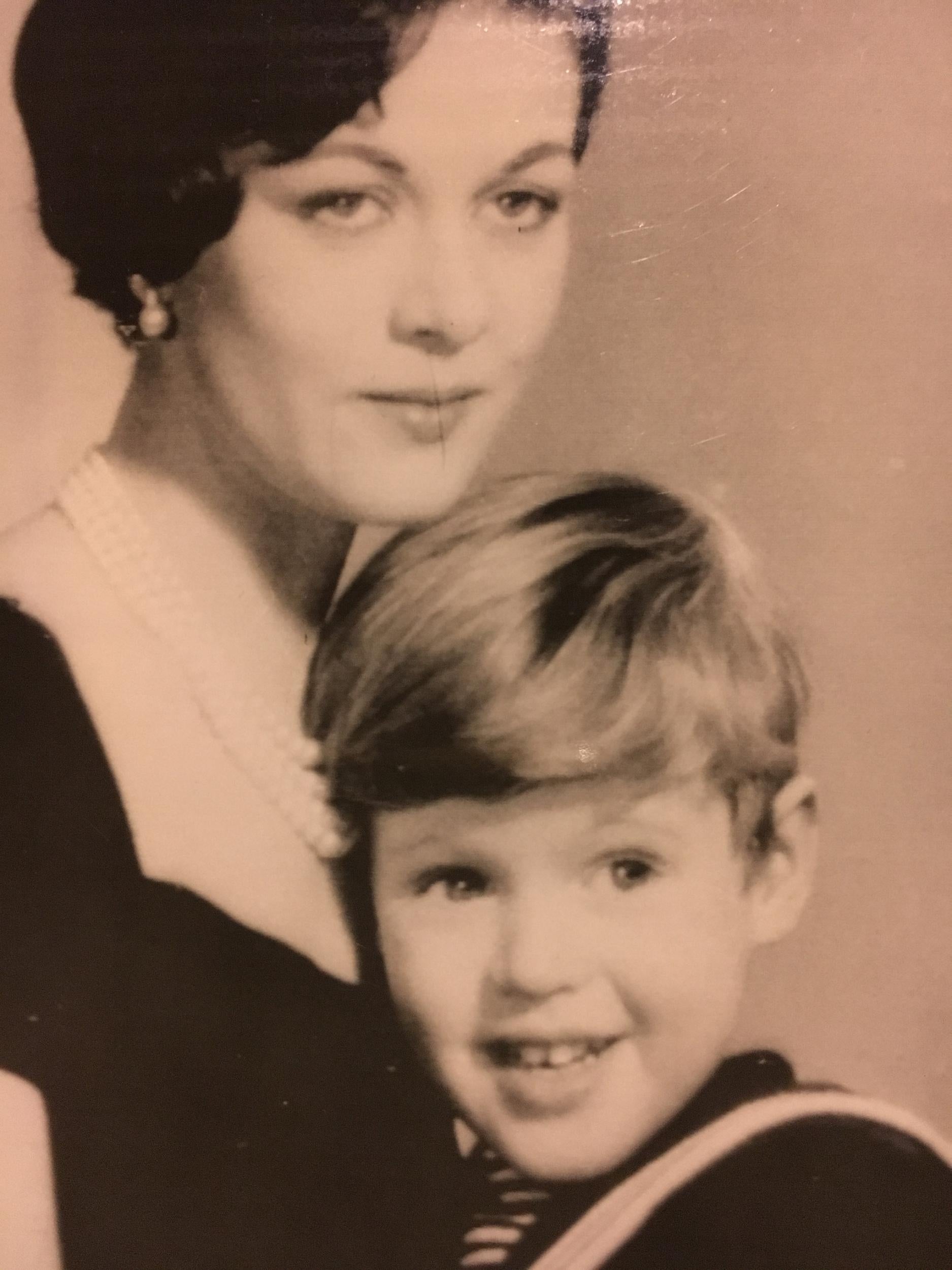

The North Shore of the island of Oahu, where Ted would go to live and die, was a long way from Croome Court, in Worcestershire, the stately home in Worcestershire that had been the family seat since the eighteenth century. Born in 1957, Ted was the son of Bill, Earl of Coventry, graduate of Eton and Sandhurst, and Mimi Medart, ballerina daughter of an American hamburger millionaire. The Coventrys – motto, “Candide et constanter” (candidly and constantly) – went way back.

The original Coventry had something to do with Dick Whittington and his cat. The archives testify to a “William Coventrie of ye Citty of Coventrie” from around the time of Chaucer, and a Henry de Coventre before him. Subsequent Coventrys lived through Plantagenets and Tudors, the Spanish Armada, rebellion, uprisings, wars, and the Industrial Revolution, and dutifully attended Balliol College or Christ Church, Oxford. Perched upon the manifold branches of the family tree were warriors and Cardinals, lawyers and ambassadors, members of the Privy Council and Lord Keepers of the Great Seal. Portraits of them hung in baronial halls, streets and workhouses were named after them.

Of course, there were occasional cads and wastrels, almost certainly scoundrels. On the other hand there was at least one Master of the Bath House. The tenth Earl (Ted’s grandfather) died heroically at Dunkirk. The original parish church of Croome had the figure of a knight painted on one of its northern windows, dressed as a Crusader, in a coat of mail and a white mantle emblazoned with a red cross, and bearing a shield Argent. And then there was Ted, on a crusade all of his own.

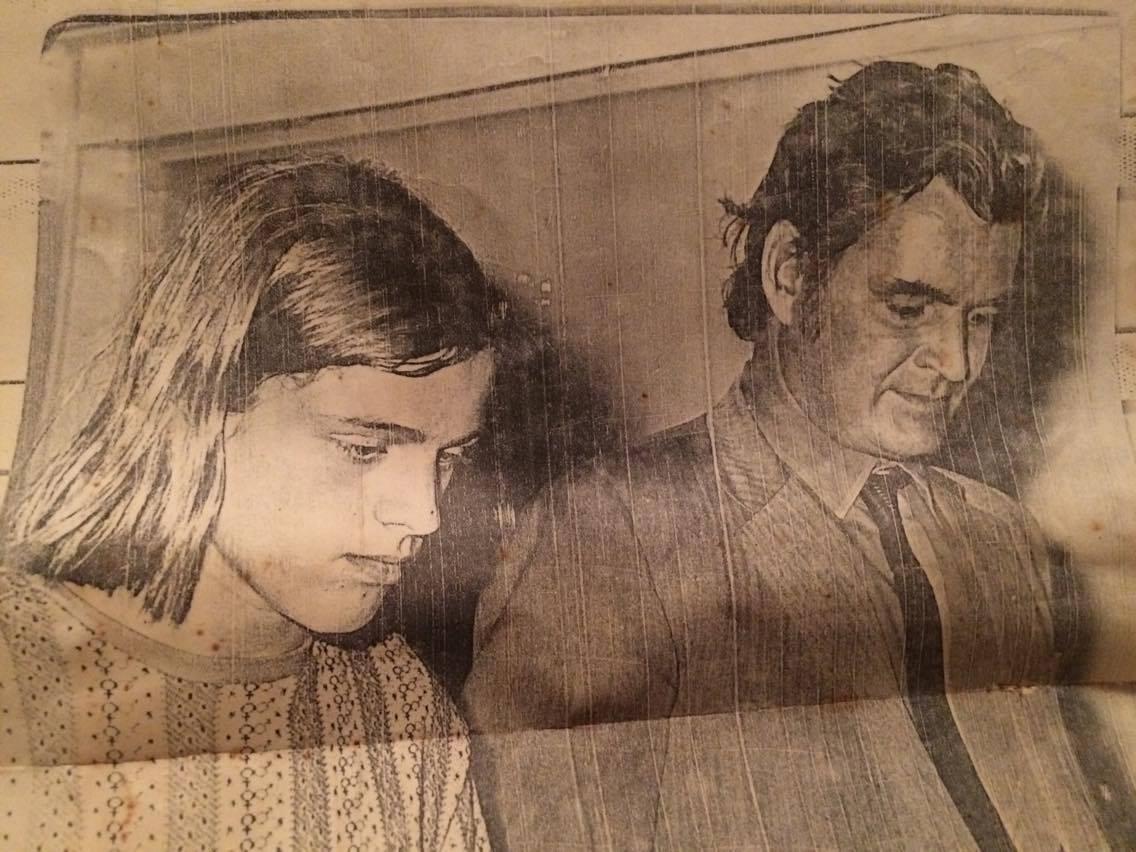

He was brought up partly in England, but – after his parents divorced – shaped largely on the beaches of Santa Monica, where he learned to surf under the auspices of Tony Alva (of “Z-Boys” and “Dogtown” fame). Aged 15 he was torn away from his sun-kissed West Coast home (“I’m an American”, he asserted in vain) and hauled back to England by an irate father, while his mother was arrested and thrown in jail for contempt of court. He dyed his hair orange in protest.

He was always up to something. While still at school he slipped a dose of rat poison into the coffee of a rival in love, who survived, fortunately. He took an A-level in photography – there is no record of his having passed. He was always broke and tried his hand, at different times, at waiter, petrol pump guy, barista, male model, coach, lawyer, but he never gave up on his quest. For Ted surfing was always a return to Eden, an escape from his demons, his own personal Shangri-La, and an impossible dream.

He surfed the world, including New York, in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty. I only once saw him really down, when he had just come 231st in the world, and vowed to go snowboarding instead. “What’s the worst that can happen?” he said, perhaps unwisely. “At least you can’t drown up a mountain.” He spent the next six months or so in traction being slowly pieced back together after taking a flying leap into the void.

Probably his best result was in 1978, at big Sunset, on the North Shore of the island of Oahu, Hawaii, when he got through to the semi-finals of the José Cuervo classic and out-performed most of the surfing establishment. His greatest tube ride, at Padang Padang, Bali – perhaps the wave of his life – is immortalised in Dick Hoole’s Asian Paradise (1984). He got caught up in the surfside wars of the Bustin’ Down the Door era – named after Rabbit Bartholomew’s provocative article that pitted Hawaiians against Australians and other “haoles”.

He was a fundamentalist where romance was concerned. He really believed that love would save him. And it would make him a better surfer too. The Surfer Guy needed a Surfer Girl by his side

It seemed like the death of aloha. But Ted always loved Hawaii and Hawaiians and finally bought a condo in Turtle Bay, at the far end of the North Shore. He studied law at the University of Hawaii with some notion of setting the world to rights, but still held out hopes of making it on the pro circuit. He became a regular at Sunset, and the bigger the surf, the better he liked it. I remember him saying that surfing Waimea Bay was “like jumping off the top of a three-storey house – and then having the house chase you down the street.” He once dragged me into some wild Sunset waves while I was peacefully surfing Kammieland, and was good enough to pay for the minor surgery I subsequently required. He was like the Pied Piper of the North Shore.

I eventually gave up writing about surfing but Ted never gave up anything. However, I knew I would one day write about Ted: he wasn’t just a surfer. He was, for example, the only pro who would regularly re-enact Second World War battles on the beach at Pipeline – with toy soldiers, tanks, and planes – while waiting for his heat. He was always dreaming, never fully satisfied.

Everything was an allegory for Ted, a symbol of something else. He was a surfer, but in his mind he was Winston Churchill or King Arthur. On a mission. A man who would be king of the waves. Restless nomad that he was, wherever he was, he needed to be somewhere else. The present was a myth to Ted, like an imaginary point in space that didn’t have any real existence.

He wasn’t a loser, he was never that, he was more not-quite-yet-a-winner. He was a modern Don Quixote, a heroic failure, a miracle of persistence, a visionary, an idealist, a dreamer. He started a charity – Excalibur – to help underprivileged and disabled kids to get to the beach and enjoy “the spirit of surfing”.

Top surfers (take Kelly Slater, for example, many times over world champion) were pure and unalloyed. They were 100 per cent surfer. They had to be. Ted, on the other hand, was barely a surfer, he was only ever clinging on by his fingertips to that mad, mysterious and mystic status.

He always seemed to have something else going on in his head, beyond the simple yet impossible ambition to become the number one surfer in world surfing: the dream of a chivalric golden age perhaps, or a better world, or “the perfect woman” (in his words), or all of the above simultaneously. He was a fundamentalist where romance was concerned. He really believed that love would save him. And it would make him a better surfer too. The Surfer Guy needed a Surfer Girl by his side.

Ted would be just over 60 now, if he was still alive. I like to imagine he would still be trying to get back on the pro Tour. At least in the Masters category. Still searching for the all-time perfect wave. As it turned out, I was given the job of writing his obituary for The Independent back in October 1997. Some said he’d died of a heart-attack. Others of an epileptic seizure.

Rabbit Bartholomew thought he had died surfing big Sunset. Or some combination of all of the above. There remained a residual mystery about exactly what had happened to him. Then a couple of years ago, Duncan Coventry, Ted’s cousin, got in touch with me to say he really wanted to know what had happened. Twenty years after the death of Ted, I set off to find out.

The problem with the North Shore is that it went straight from pre-truth to post-truth. The mythic mentality that is pervasive there suited Ted down to the ground. But it also means that when you die in Hawaii not too many of the inhabitants care about exactly how and why and who did what to whom, those basics that anywhere else would count for something. On the North Shore, everybody lies, to themselves and others. And they have good reason, in certain circumstances, to avert the gaze. The code of omertà. The North Shore can legitimately lay claim to some of the greatest breaks on the planet. But it is a place of heartbreak too.

Trying to get some answers, I retraced Ted’s footsteps, posthumously piecing him back together again, body and soul. I spoke to his old childhood friends, in Devon, in New York and on the West Coast, in Hawaii and New Zealand. I tracked down his ex-wife Susan in Australia. They illuminated episodes in his life. But wherever I went, it kept coming back to a woman called “Lola”. I met her once in an “exotic dance” club in downtown Honolulu: she was naked and sitting on Ted’s lap at the time. Ted had a notion that she, at last, fitted the bill of “the perfect woman”. They were going to get married. “It’s the real thing,” he told me. But maybe her gangster boyfriend, “Pit Bull”, had other ideas. Trouble in paradise was looming.

“Life is short,” Ted wrote in a friend’s journal, aged 39. “Don’t waste it!” Maybe he’d had some presentiment of doom. He made it to 40. Was his premature death down to “natural causes” – as the police maintained – or did it have something to do with the two heavy dudes who came knocking on his door, one fine day, and warning him to leave Lola alone, unless he wanted to find out if he could surf on just one leg? After hunting down his death certificate and going to Hawaii 5-0 HQ in Honolulu, I was able to locate “Dan”, the last man to see Ted alive, who feared he would be fingered for Ted’s murder.

I took one of Ted’s old Excalibur boards out at Haleiwa, on the North Shore of Oahu, last year. A magic board, shaped like a sword. I felt as if I could go and conquer the world with it. As I was coming up the beach I was stopped by a bearded mariner, en route from New Zealand to Alaska. “Great board,” he said. He recognised the sword motif and recalled seeing Ted surfing at Sunset many years before. “I surfed bigger waves back then. But it was huge. So I stayed out on the shoulder. There were a few guys who were standing right up in the tube. Ted was one of them. Three or four seconds, really solid tubes. Just kept going on. Wave after wave, set after set. It was one of those days. Endless.”

Trouble in Paradise: Part 2 in tomorrow's Daily edition

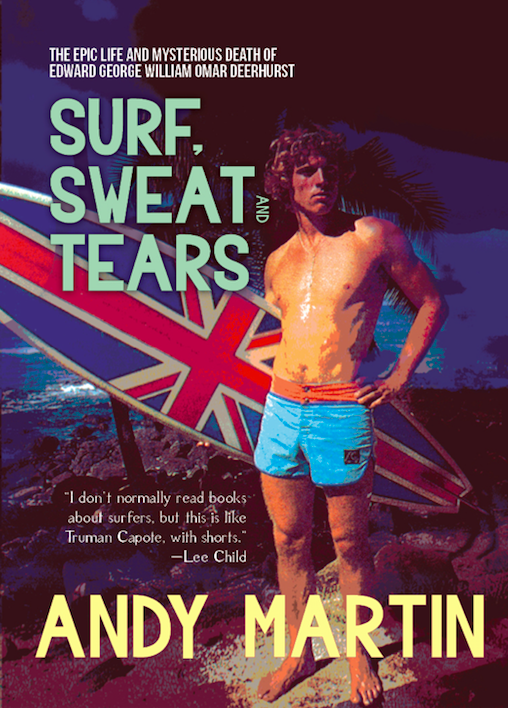

Andy Martin’s Surf, Sweat, &Tears: the Epic Life and Mysterious Death of Edward George William Omar Deerhurst is published by OR Books

Use code SURFSWEAT15 to get 15 per cent off at the following link...https://www.orbooks.com/catalog/surf-sweat-and-tears/

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments