‘Shameful, incompetent, humiliating’: The parallels between the Suez Crisis and the evacuation of Kabul

During this summer’s events, commentators were quick to draw parallels with the Suez Crisis of 1956. But the recollections of Mick O'Hare’s father, a signalman at the time, differ from accepted history

On Bonfire Night 1956, signalman Keith O’Hare sat at the end of his bunk at the Catterick army camp in North Yorkshire waiting to be sent into action. What would become known as the Suez Crisis had kicked off seven days before when Israeli troops invaded Egypt. British and French divisions were being mobilised, ostensibly as peacekeepers, but covertly to support Israel in seizing control of the eponymous canal.

Over the summer just passed, commentators and politicians have lined up to draw parallels between the scrambled evacuation of Kabul and historical precedents. For the US, overtones of the flight from Saigon in 1975 were never far from the headlines. But for Britain, one word appeared more often than any other. And that word was “Suez”.

“Shameful”, “incompetent”, “humiliating” – the accusations in both the leader columns of the press and Hansard became repetitive. Both sides of the Commons lined up to take potshots at Boris Johnson’s government and former foreign secretary Dominic Raab’s handling of the evacuation. Conservative chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee Tom Tugendhat had this to say: “The situation in Afghanistan was, quite simply, the biggest foreign policy disaster since Suez.” Northern Ireland secretary Owen Paterson added that it was the “UK’s biggest humiliation since Suez”. It seems what happened to the nation in the Middle East 65 years ago this week permanently scarred the British political psyche, its fallout still resonating down the years.

Not that signalman O’Hare would have worried about humiliation or foreign policy disasters. In the end he was simply pleased the whole thing was called off at the last minute as, under pressure from the United States, Britain and France abandoned their vainglorious attempt at neo-colonialism. His surname isn’t coincidental – protagonist and author were father and son, and he had a whole lot to say about Suez in the years after, much of which I recorded. I have been listening to his words again as the 65th anniversary of Suez approaches.

But why was Suez so humiliating? It’s been said that it marked the end of two empires, the British and the French, and that it was the moment both realised they were no longer world superpowers. The mantle had passed to the United States and the Soviet Union. But does that explain why the Europeans stuttered so calamitously on the world stage? Was it a swaggering attempt to turn back the clock to the empire-building days of the previous century, or unwitting patriarchal imperialists still believing their way was the right way? And was it really the point in 20th-century history that the old guard was routed; sent back to its fading imperial capitals with its tail between its legs?

In July 1956, president Gamal Abdel Nasser of the newly established Egyptian republic created in the aftermath of the 1952 coup d’état that toppled King Farouk, nationalised the Suez Canal that ran directly through Egyptian territory linking the Indian Ocean via the Red Sea with the Mediterranean. The canal, as it is today, was strategic both commercially and militarily. It had been built by a Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps between 1859 and 1869 and had, prior to nationalisation, been owned primarily by British and French shareholders.

Unsurprisingly the canal was a key strategic asset throughout the First and Second World Wars. Following the end of that latter conflict it became a conduit for the shipment of oil, the great commercial driver of the second half of the 20th century, from newly enriched Gulf states. It effectively provided a commercial lifeline from western Europe through the Indian Ocean to Australia, New Zealand and beyond. But Britain and France no longer had any control over who or what could use it. Nasser had negotiated the withdrawal of the last British garrison. Egypt, once a British protectorate, was suddenly no longer in thrall to London. And the French had a further beef with Nasser – they believed he was supporting Algerian rebels opposed to French colonial rule.

The British prime minister was the Tory Anthony Eden, once Winston Churchill’s foreign secretary. Patrician and a believer in British exceptionalism, he would become the last British PM to believe imperialism had not run its rather discredited course. More than anything, he seemed unaware the world had changed around him. When the last of Britain’s troops left Egypt and Nasser nationalised the canal his reaction was straight out of the colonialists’ playbook. His loathing for Nasser was uncontrollable, bordering on the irrational. He announced that Nasser “should not have his foot on our windpipe”. When the Foreign Office refused to contemplate assassinating Nasser he sent in the infantry.

When Nasser refused the offer of British and French ‘help’ they invaded anyway and secured the canal, although ironically it was effectively blocked anyway

And Eden was deceitful too. The British and French concocted a plan with Israel, a nation also in conflict with Egypt which, since the establishment of the Jewish state in 1948, had denied Israeli ships passage through the canal. Israel invaded Egypt on 29 October with the – proclaimed – aim of securing the canal. They quickly occupied the entire Sinai Peninsula and took control of the waterway. Britain and France offered to intervene, purportedly to separate the warring Israeli and Egyptian forces and to secure the canal for international shipping. It was a smokescreen. And it was one the rest of the world saw through despite denials from the tripartite aggressors.

Suez was, of course, played out through the prism of the Cold War. In throwing off European colonialism African nations swung in and out the sphere of the capitalist west and the Soviet Union. In 1956 Egypt had secured funding from the latter to build the Aswan High Dam on the Nile and was taking arms shipments from the Soviet Union’s Warsaw Pact ally, Czechoslovakia, which deeply concerned the Israeli government. Meanwhile there was the concurrent Arab-Israeli conflict born out of the creation of the state of Israel from lands the Palestinian Arabs – with Egyptian backing – claimed as their own, a conflict that is still playing out today.

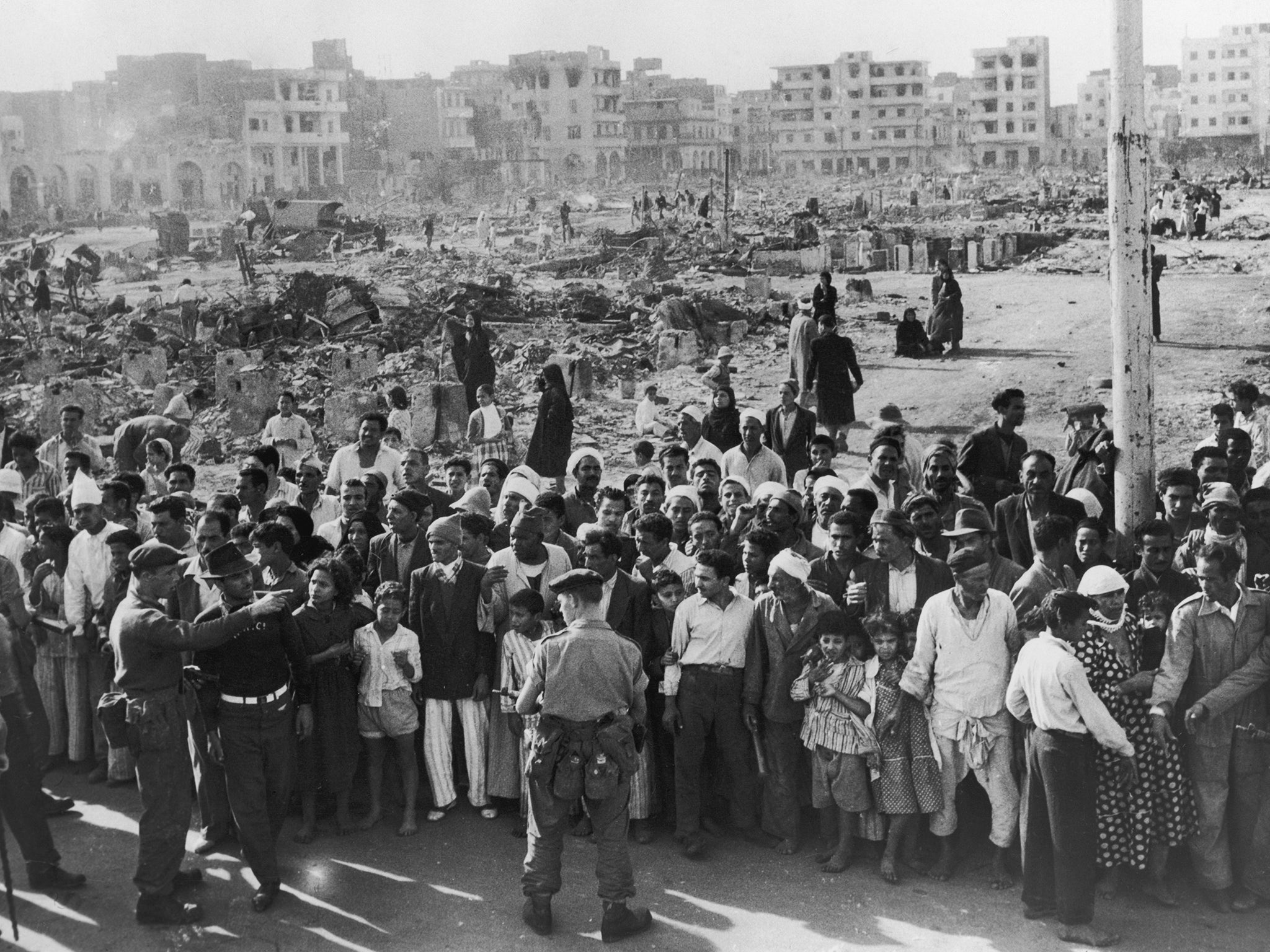

When Nasser refused the offer of British and French “help” they invaded anyway and secured the canal, although ironically it was effectively blocked anyway as 47 ships were scuttled or otherwise sunk following the invasion, making the waterway unusable. The Soviet Union, already embroiled in the Hungarian uprising of 1956, threatened to defend its new Egyptian ally; premier Nikita Khrushchev even talked of missile attacks on London and Paris to protect “free nations against western imperialism”.

Stupidly and duplicitously Eden had failed to inform the US president Dwight D Eisenhower about his invasion plans. The Americans were outraged and immediately saw the British and French action for what it was. Horrified the detente that had maintained the world’s unsteady peace since the rise of the Iron Curtain might now unravel, they instinctively understood that conflict in the Middle East was contrary to US interests, and were terrified of a Soviet occupation of the region. Eisenhower demanded, via the threat of financial sanctions on the British and French governments, as well as through the United Nations Security Council, that London and Paris withdraw their troops. It had the desired effect. There was a run on the pound, petrol rationing was reintroduced as the oil supply diminished – the ironic coincidence of this year’s anniversary might have been lost on those who were queuing at petrol stations last month – and, despite right-wing press support for the invasion, public backing in Britain – and France – plummeted. “Law Not War” was the cry on the streets.

Labour Party leader Hugh Gaitskell railed against the intervention and crucially there was dissent in the Tory ranks too. A ceasefire was struck, hostilities ended on 8 November and by the end of December the troops were gone, as was Eden. On 19 November he left London to recuperate in Jamaica at the home of James Bond author Ian Fleming, from the trauma and the surgery he had undergone earlier that year, eventually to resign and be replaced by Harold Macmillan in January 1957. Sixteen British soldiers and 10 French died, dwarfed by the 172 Israelis and possibly 4,000 Egyptians who perished. Yet the impact on British and French psyches was enormous. Britain would begin increasingly to rely on the US when it came to foreign policy while the French left Nato and turned towards building a partnership with Germany and continental Europe, which would eventually lead to the creation of the European Union.

Nirav had told him that when a Gurkha draws his knife, or kukri, tradition dictates that he cannot resheath it until blood is drawn

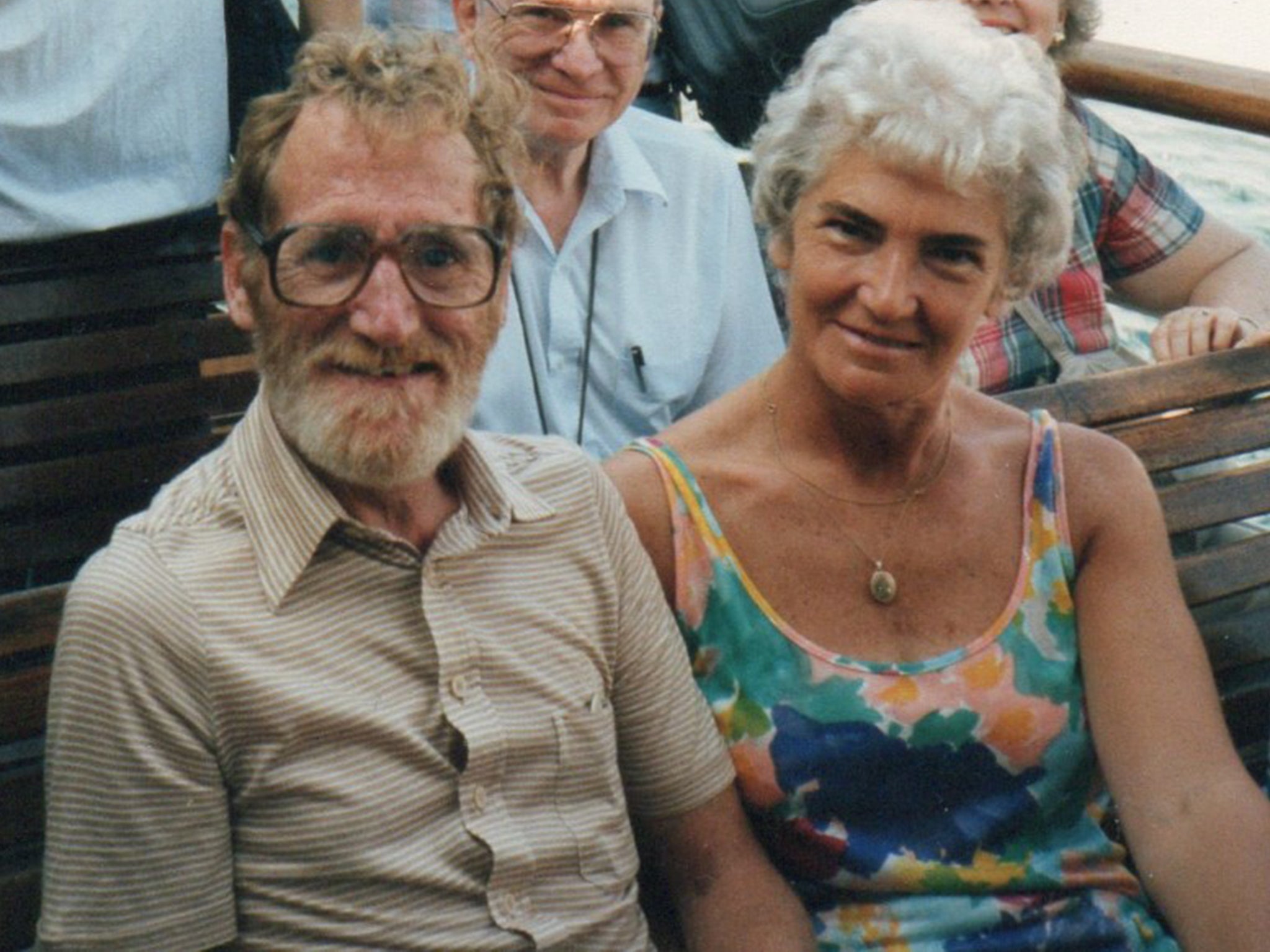

Listening to the recordings of my father now, talking about Suez, it’s clear his version differed somewhat from that generally accepted. And while his part was a mere cameo and clouded somewhat by his political world view, hearing him talk intelligently and passionately about it maybe deserves an audience wider than his immediate family so many years after the event.

“Eden was rash and out of his depth and out of his time,” said my father “And Eisenhower was scared. Scared of nuclear war, which is a wise thing to be scared of. He knew a peaceful world, by whatever means, was a more prosperous one. Pragmatic politics overcame the politics of the past.”

Signalman O’Hare had a complicated relationship with politics. As a person he was at turns depressive and moody, then comedic and ironic. It was difficult to ever figure out what he was for, but the family sure as hell knew what he was against. The absurdities of politicians and politics in general were never far from his cynical ire. He did, however, believe that the franchise was a precious gift to individuals in what he termed “so-called democracies”. And he turned out at every election although we had no idea for whom he voted. He appeared able to despise politicians of all hues pretty much equally. Maybe he spoilt his paper.

He loathed charity, believing it abrogated the government from taxing wealth to fix problems, and it acted as a safety valve for people pretending to be philanthropists, while paying less than they would otherwise in tax to the benefit of society. He appeared at times libertarian, of the left or the right, we couldn’t tell, but he hated national service on the one hand because it was mindless, soulless and monotonous, and on the other because he loathed war and killing more than he loathed charity. Fortunately he had secured his service in the Royal Signals allowing him to indulge his interest in electronics and communications. But as much as he detested his two years in the army it did offer him a direct insight into the military. And it guaranteed that we heard his opinions on Britain’s involvement in Suez – among many subsequent conflicts – numerous times before he died in 1995 (of Crohn’s disease, which caught up with him at the age of 59. Ironically the army eventually admitted it had been firstly misdiagnosed and then exacerbated, if not caused, by his time in the military).

“It’s said that Eisenhower later regretted not supporting Eden,” he said. “But that is Eisenhower viewing the world with hindsight. He thought that endless conflict in the Middle East, much of it brought about by the actions of western governments, could have been avoided if Nasser had been deposed. It wasn’t so simple. And more than anything Nasser had every right to claim the canal. It ran through his country and was built by his people. And he never even threatened to block British shipping. Any notion of fairness meant he should have some stake.”

My father was obsessed by “fairness”. After he’d admonished me as a child for some minor misdemeanour he later realised he’d been wrong and bought me a set of new tennis balls. We weren’t particularly wealthy and I’d been using threadbare versions all summer. I treasured them because he was never a person given to shows of affection or largesse. But in this case he believed he’d been unfair. It was his thing.

Long before the pension rights of Nepalese serving in the British Army became a contemporary political issue, my dad campaigned for equal retirement rights after befriending a soldier from the Royal Gurka Rifles, Nirav Tharu, from Kathmandu. I recently found an English/Nepali dictionary Nirav had given him as a gift, and the palm of my father’s hand bore the scars of their friendship. Although it’s actually a myth, Nirav had told him that when a Gurkha draws his knife, or kukri, tradition dictates that he cannot resheath it until blood is drawn. Their bond existed until Nirav drowned in the 1970s.

It wasn’t so much the end of empire – the British must surely have realised that had happened in 1947 when India won independence

“I saw how white officers treated Nirav despite his loyalty to Britain,” said my father. “And there was more than a hint of racism in Britain’s attitude to Suez. The establishment hated the fact that people whom they regarded as inferior and whom they once controlled were now taking charge of their own affairs.” As a signalman my father recalled daily overhearing furious debates about what the “bloody wogs” were up to from both politicians and military leaders. “They were racist to the core. They had an offensive term for anybody not white and middle or upper-class, but also genuinely believed that it was their duty to protect unsuspecting minds and ‘inferior’ races from the perils of communism and their own lack of moral and political direction. They still believed they were their superiors and should be listened to,” he added.

It may have been his Irish/Yorkshire ancestry which gave my father an innate mistrust of Westminster politics. Certainly he had no affinity with the elected politicians and parties that constituted the House of Commons. He seemed to equally despise left and right as it was represented in parliament – he thought Thatcher cruel, Michael Foot useless, Jeremy Thorpe ineffectual, Paddy Ashdown too earnest, Harold Macmillan indolent and a flunky, Harold Wilson a betrayer of the working class and Edward Heath a lackey of the establishment. Nationalists of whatever hue were divisive bigots. The list of derision was pretty much endless although intriguingly he reserved a sliver of respect for politicians who “didn’t lie”. Thus Thatcher and her socialist nemesis Tony Benn among others were grudgingly offered a tiny scrap of acknowledgement. What he would have made of Boris Johnson’s “provable untruths” and the mendacious campaign that led to Britain’s departure from the European Union, and it’s pseudo-imperialistic underpinning, one can only wonder. But lying was, to him, the mark of the scoundrel, and it was a charge he laid repeatedly at the door of Eden.

“This man of integrity, the archetypal English gentleman, the patrician who knows what’s best for the little people. All that ‘my word is my bond…’ Some say his judgement was impaired by illness [Eden’s surgery meant he was still taking both sedatives and stimulants at the time of Suez], but if that’s so he should not have been running the show. He lied to the nation and the world about why he was sending British soldiers to Egypt. He even planned to requisition the BBC to sell the nation his lie, a fabrication that would kill his own people,” said my dad. “And as a consequence so many died. I could have died. It was a ludicrously excessive reaction. And it was all predicated on a lie.” And he added: “At least Palmerstone had the courage to admit that Britain had no allies and no enemies, only interests,” referring to Britain’s phlegmatic and pragmatic foreign secretary of the mid-19th century. “Eden personally may have been humiliated, as much for his pathetic attempt at sleight of hand, and I hope he was, but the biggest shock to the established order in Britain was that it still expected the world to listen when it didn’t want to and didn’t have to.”

So, end of empire? It’s been the conventional verdict of history books for 65 years now and become pretty much the accepted definition of the events and outcomes of the autumn of 1956. The Times wrote this of Eden on his death: “He was the last prime minister to believe Britain was a great power and the first to confront a crisis which proved she was not.”

Yet although those history books may record otherwise, signalman O’Hare’s analysis differed. “It wasn’t so much the end of empire – the British must surely have realised that had happened in 1947 when India won independence,” he said. “And not only had a large part of the empire gone geographically, Britain also lost the services of hundreds of thousands of Indian soldiers who had helped police it. It wasn’t the end of empire, no, it was more the start of self-determination. There was complete surprise on the part of the British (and the French) that other people didn’t share their worldview. It’s also been pinpointed as the end of Britain’s worldwide influence. But it wasn’t, it was an awakening, a realisation that there were alternatives beyond the status quo. Nasser said it’s Egypt’s canal, it runs right through the middle of our country. And jaws dropped in Paris and London.”

I loved my father enormously, although our arguments raged long and hard and ran deep, but in retrospect, I reckon on this one he had a point. Britain’s empire was already dead, killed off by the Second World War. It just needed an event like Suez to make a still-patrician government realise it. My father’s words were those of someone who was – almost – on the spot. Certainly he had an opinion which would not have been heard from the likes of a conscript in the ranks at the time. Whether or not he was correct, it was an opinion arrived at by experience and intellect.

Humiliation is probably the right word to describe what has just happened to Britain and its western allies in Afghanistan, but it’s not quite the right word to describe Suez. Or at least not the only one. Surprise, shock, revelation and disbelief are all words my father would have chosen in its place. And maybe, perhaps, anachronism?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments