‘We’re not looking for bodies anymore, just scraps of DNA’

During a week of bloodshed in June, protesters in Sudan started vanishing. Seven months on dozens have still not been found. Bel Trew talks to the families of the disappeared

How can a person vanish without a trace? This is the question Sumia Osman, 58, asks herself every week, as she trawls through the hospitals, morgues and police stations in Khartoum looking for her missing son Ismail. The 24-year-old Sudanese student had joined his country’s revolution last year while on holiday from Maryland, in the US, where he was studying psychology.

He was last seen by his uncle on the evening of the 7 June getting into his car. There was a nasty edge to that night in the Sudanese capital. Members of the feared Rapid Support Forces (RSF) were playing “cat and mouse” with protesters who had tried to build barricades around the neighbourhood, the family said.

Four days earlier, the same paramilitary group had raided an anti-government sit-in killing over 100 people, and beating and raping others, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW). From that moment dozens of people who participated in the rallies began disappearing. Some have since been found dead. Others reappeared months later showing signs of physical and psychological torture.

But more than seven months later, the fate of nearly 30 people including Ismail, remains unknown. Ismail al-Tijani’s family has just one clue: his mobile phone records show he made a final call from an area on the other side of town, which is home to an RSF base.

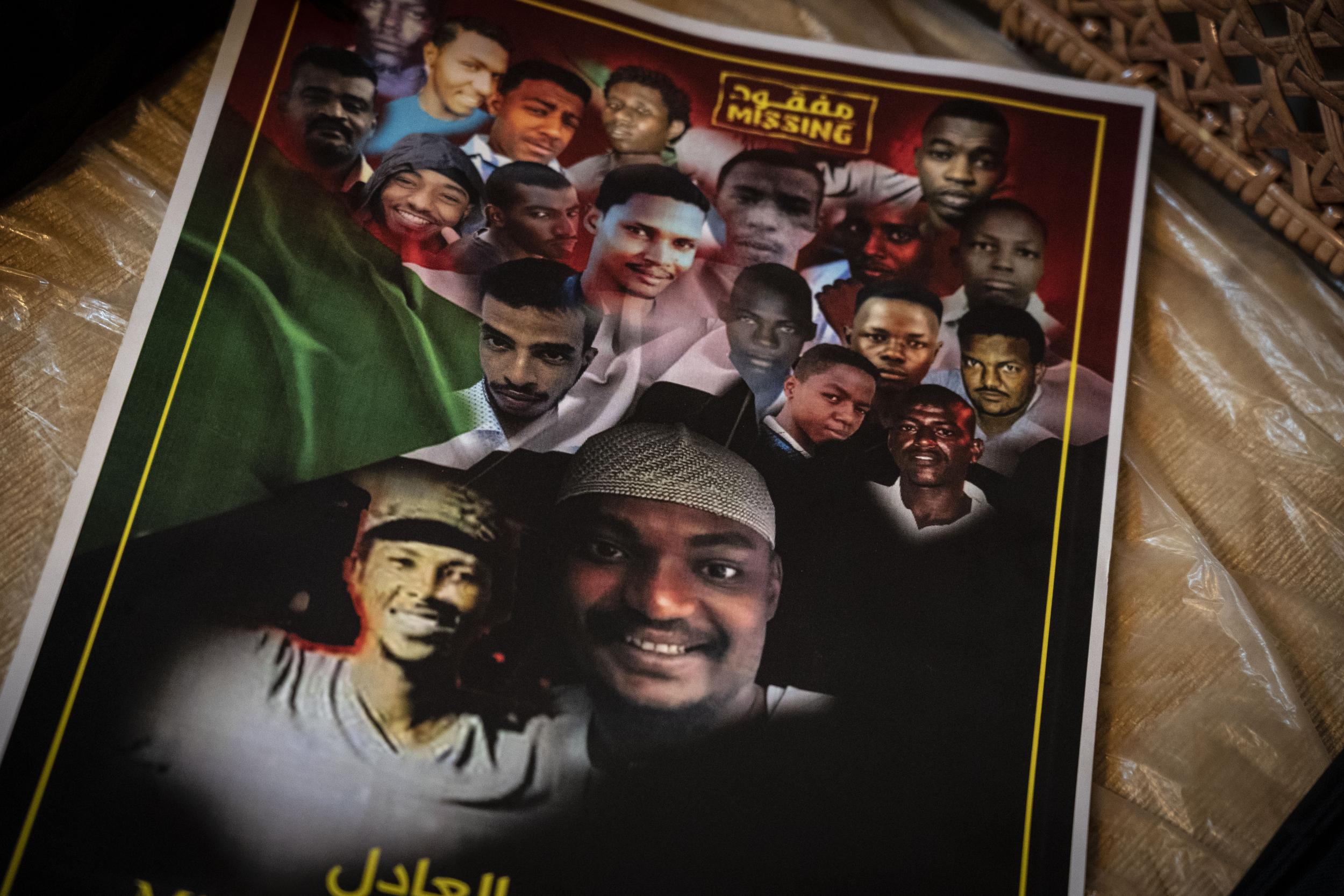

“Every five or six days all of us who have missing children visit the hospitals, morgues and police stations together. But we are told there no bodies. We don’t know why they lie to us,” Sumia says, sitting next to a poster of her son smiling as he makes the peace sign to the camera. The mother-of-three explains how the family is exhausted and broke.

“We don’t know whether he is alive or dead. We know nothing about him. At this point, we are not even looking for a person, just any scrap of DNA.”

Across the city, these words are echoed by another desperate mother, Mona Beloula, 48, whose 20-year-old son also vanished the same week Ismail did. Negmeldeen al-Bawadi, a student, was last seen heading to the sit-in just hours before it was attacked on 3 June. No trace of him has ever been found. “I’ve consumed all my powers, both physical and financial, trying to find my son,” Mona says in desperation. “At this point, I have stopped worrying about whether he is dead, I just want to bury his body. But I do not even have that.”

After months of nationwide protests, last April Sudan’s military overthrew the country’s infamous president Omar al-Bashir, who is wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes and genocide. In the aftermath, the armed forces struck a power-sharing agreement with the revolution’s civilian leaders. An 11-member joint council currently rules the country, headed by army chief Lieutenant General Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan. His deputy is the RSF’s chief commander, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known by his nickname “Hemedti”.

Post-revolution there were signs of positive change until 3 June when security forces, many of them dressed in RSF uniforms, stormed the main sit-in in Khartoum and opened fire on unarmed protesters. They also raped, stabbed and beat people, according to a HRW investigation.

At the time witnesses told The Independent they saw soldiers throwing bodies into the Nile. Corpses were later retrieved from the river with bricks tied to their bodies and gunshot wounds to their heads and torsos. One of them was Qusai Hamadtu, 23, a law student, who was last seen in a mobile phone clip taken during the clearing of the encampment.

“In the video he is looking for a safe place to hide on Nile Street,” says Najla Noreen, 35, Quasi’s relative and a fellow activist. Four months later, activists looking for missing protesters, stumbled upon his corpse and that of another young man called Hassan Osman Abu-Shanab, in a morgue in Omdurman, the neighbouring city to Khartoum. The police admitted they had found the bodies in the river days after the break-up of the sit-in, but morgue officials had said nothing until October.

Najla says Qusai’s body was riddled with bullets and his feet had been shackled to cement blocks. “I saw how brutal the security forces were that night. It was like a personal vendetta,” she adds.

Hemedti, whose forces have been accused of genocidal violence in Sudan’s western region of Darfur, has repeatedly denied his men were involved in the killings and disappearances. He told The Independent rogue elements within the security forces posed as RSF officers and instigated the violence on 3 June in an attempted “coup”. The RSF has opened an internal investigation into the killings. The civilian-led government instigated an official probe into the missing protesters.

But the bloodshed has left many revolutionaries uneasy about the future of the country and distrustful of the ruling civilian and military council. The continued disappearance of dozens of people and the reappearance of several protesters months later in morgues or alive but covered in torture wounds has only underscored this distrust.

Fadiya Awad from “The Missing Initiative”, set up by the families of lost protesters, says they have had little help from the authorities locating their loved ones. “Our initial statistic was that 100 people were missing. We found some of them dead in morgues or in different hospitals with injuries,” she explains. “Right now, we know of 29 outstanding missing person reports, including Ismail,” she adds.

Among those found were people who mysteriously re-appeared in terrible shape apparently so traumatised or terrified they could barely speak. Wail Ali Saeed, a leading member in the Alliance of Sudanese Lawyers, which is gathering evidence on the disappearances, tells The Independent they often bear signs of “brutal beatings and the use of electric shocks”.

Like Awad and Ismail’s family, he believes they may have been held in secret detention centres. “They were found in a miserable condition just thrown on the street; we are still trying to find out where they were,” he says.

Awad says piecing together what happened is difficult because people are often too distressed or scared to remember. “Two men, who we believe were held in the same prison cell, reappeared in different locations months later, one abandoned in a public bus station,” she explains. “They are being treated for trauma and remain very disturbed. One of them doesn’t fully remember what happened to him, but there are torture marks all over his body.”

Another protester, Amal al-Gous, a tea-seller who was among the 500 or so street vendors who joined the revolution, also reappeared months after vanishing during the 3 June clearing of the sit-in. Her story is eerily similar. “No one knows what happened to her. Her family searched every morgue, hospital and police station for three months until suddenly her phone switched on,” says Awadeya Mahmoud Koko, 56, an activist and head of the tea-sellers union that is supporting Amal’s family.

“A group of men picked up Amal’s phone but wouldn’t talk. She was found by the side of a road, covered in torture wounds so traumatised she couldn’t talk.”

Koko, 56, says she believed mounting public anger about the missing protesters forced the security forces to suddenly “reappear” people months on. “I hope that once Amal recovers, she will be able to explain what happened,” she adds.

Ismail’s family had hoped he might reappear, but six months on that is looking increasingly unlikely. They have repeatedly appealed to the authorities for any help. “In the beginning, we were all in the dark there were so many missing people. But after massive protests and with public pressure, it was clear someone started releasing people who were alive but are now traumatised,” Sumia continues. “Bodies also started appearing in morgues. But for us, still no Ismail,” she adds.

Together with police, the family meticulously pieced together Ismail’s timeline to try to shed light on his fate and the fate of others like him. The sinister sequence of events points to a grim ending for the student. At 7.15pm, a quarter of an hour after his uncle saw him get into his car, Ismail called his friend Mohamed to say he could not meet for coffee that evening. Five and half hours later he called his cousins, who were both at a wedding that night. No one knows what Ismail did in the interim or what his final words were.

The signal was not strong enough when he called his cousin Razi at 12.45am, according to phone records the family showed The Independent. Fifteen minutes later he tried his cousin Amro, who said the wedding reception drowned out Ismail’s voice that was partially muffled by the sound of wind in the background. I’ll call you back, Amro had shouted back. But when he tried Ismail’s phone it was switched off for good.

The family said two cell-phone towers traced the calls to farmland nearby Shambat, a twin city to Khartoum about 20km north across the Blue Nile from his home in central Khartoum. The area houses sprawling university campuses, agricultural lands and also, according to the family, an RSF base. Sumia said it was strange for her son to be there given he barely knew his way around town.

It was only his second visit to Sudan. He had lived for 14 years in Saudi Arabia and went to the US for university. The last time he had been Khartoum was when he was just 11 years old. “He doesn’t have friends, he doesn’t know the area, he doesn’t know the streets well,” she says.

And so the family spoke to members of the RSF privately, begging them for any clues. “One soldier admitted they’d seen him but couldn’t remember when and where. Another told us they were sure they’d also seen Ismail’s face before,” she adds. Ismail’s car was found nine days after he vanished, abandoned on Mak Nimr bridge, a 20-minute drive south of Shambat and 15 minutes from his home. There were no blood traces in the car or usable DNA samples, the family said. Nothing had been stolen: Sumia’s glasses were still inside the glove box. The police dredged the Nile beneath the bridge and found nothing.

Too many days has past and the security footage from the bridge had been erased. The behaviour of police sniffer dogs pointed to someone exiting the vehicle, entering a new car and driving off, Sumia adds.

With so little information Ismail’s relatives believe he might have been killed. Saeed, the lawyer, says people have begun speculating about mass burial sites. “There is the possibility of a mass grave. Some videos have been shared showing soldiers digging. But we have no concrete information,” he tells The Independent. “The million-dollar question is if anyone will be found responsible for this because it happened after Bashir was toppled. It’s politically awkward.”

The families say they have not yet reached the point of seeking justice. They are still looking for any trace of their loved ones. Stuck in the purgatory of not knowing, all they can do is endless laps of the morgues, hospitals and police stations in the small hope of finding something. Sumia says as time goes by the family is increasingly worried Ismail will lose his place at university in America. He dreamed of graduating from the US and “doing great things for his family, for his nation, for the Sudanese people,” she says.

Mona, meanwhile, implores the authorities for any help in the search. “I am hurt in a way no one but God can truly understand, I just want to know where he is,” she says her voice cracking. “I can’t walk like I used to. I can’t do anything like I used to. I’m broken. The world is a different and darker place.”

Read Bel Trew’s A Nation on the Edge series here:

- ‘Isis will be small fry’: Sudanese PM warns country will implode unless US sanctions are lifted

- ‘It’s like Bashir is still here’: Inside war-ravaged Darfur where deadly violence is killing the revolution

- Women do not protest to be fetishised – their bravery should be better supported

- ‘It’s a luxury to go to The Hague’: Sudanese dictator Bashir faces trial verdict – but victims fear he’ll evade justice

- Genocide, gold and foreign wars: Sudan’s most feared commander speaks out

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments