How a humble Greek water carrier won the first Olympic marathon

With the Olympics starting tomorrow, Mick O’Hare looks back to the first modern marathon in Athens in 1896 and why a Greek just had to win it

The Greeks were getting a bit desperate, if not to say embarrassed. The spiritual home of the ancient Olympic Games had been an obvious choice for the first Olympics of the modern era in 1896, but despite the numerical superiority of its athletes, not a single Greek winner had emerged on the centrepiece of the games – the running track.

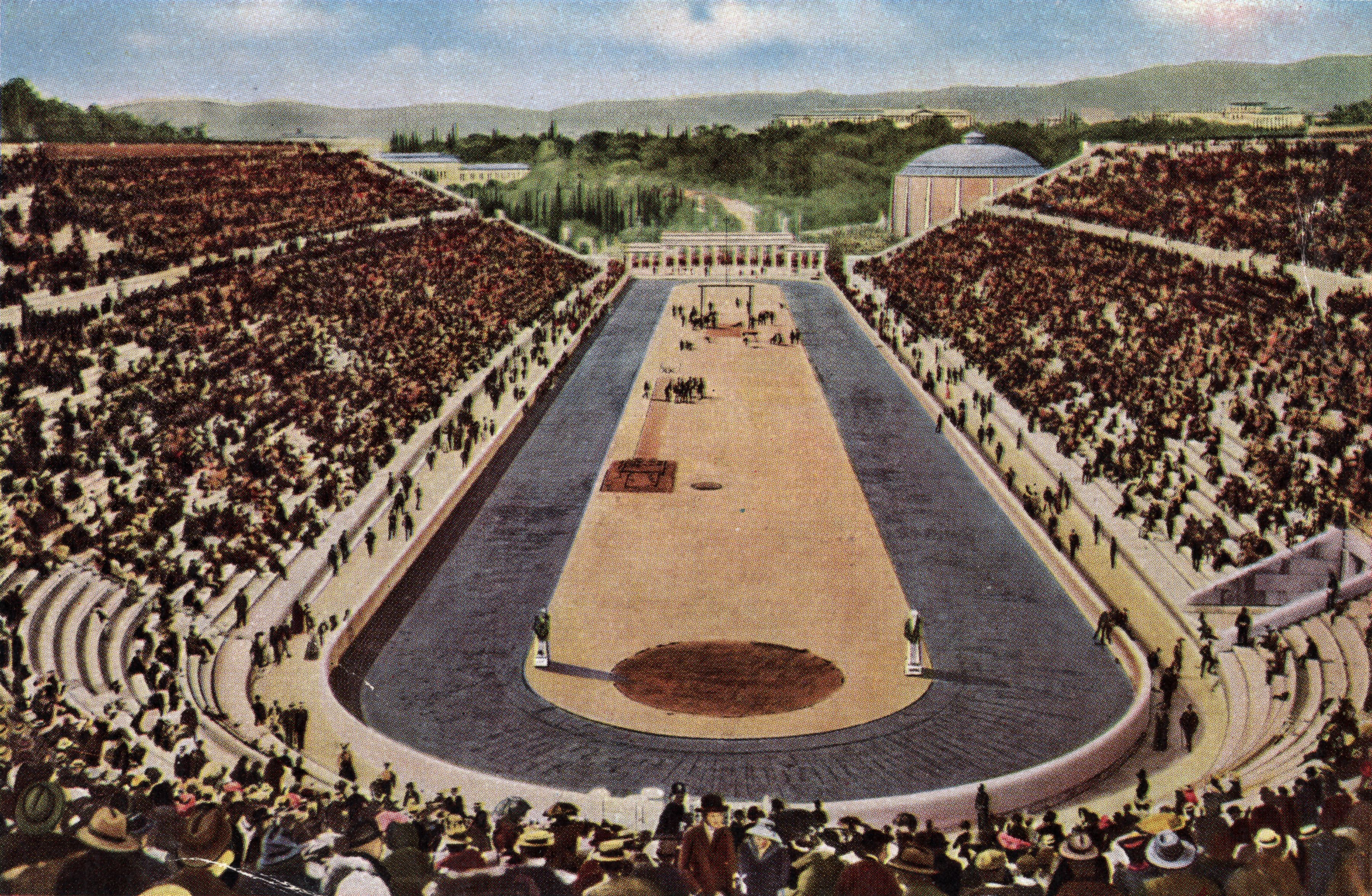

Greece had been expected to revive its formidable athletic legacy, dating back millennia, in the ancient, restored Panathenaic stadium in Athens. But there we were, on the final morning of the games and the civilisation that gave track and field athletics to the world was still waiting for its first champion. The Olympic motto, Faster, Higher, Stronger, sadly did not seem to apply to the host nation. When Greece failed to win the discus – an event linked with Hellenic antiquity and rarely ever competed for outside Greece – the sepulchral mood was complete.

Disappointment gave way to introspection. It looked like the Greeks had been vanquished at their own sport and on their home turf by a world that now ran faster, jumped higher and threw further. But there was one event remaining, and it was one that had been devised especially for the new Olympic era. The marathon race was intended to honour Greek sporting and military history. In 490BC, Pheidippides, the Greek soldier, ran almost 25 miles from the battlefield of Marathon to Athens with news of the Greek victory over the Persians. It is a story woven deep into Greek folklore.

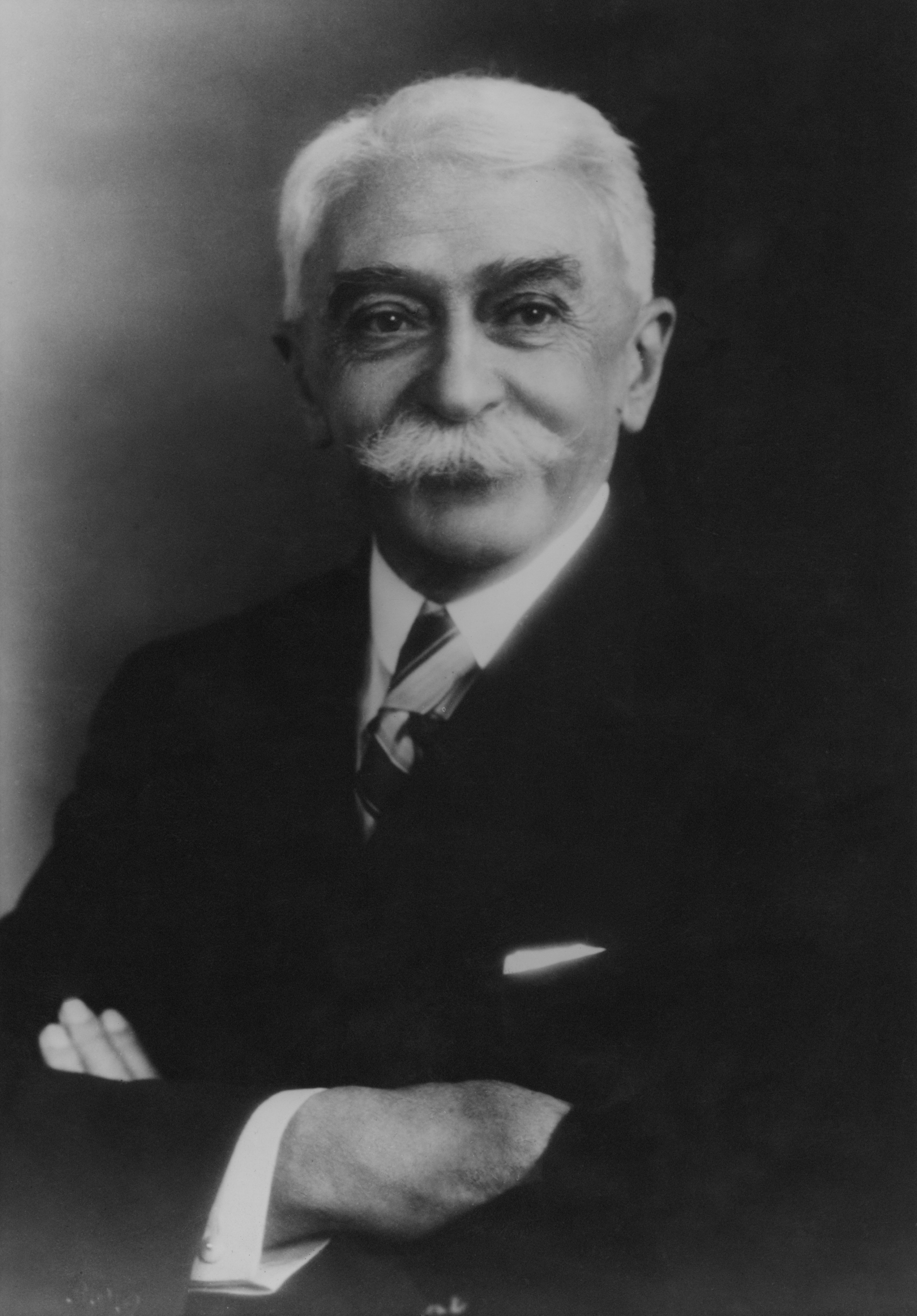

When Baron Pierre de Coubertin was planning the revival of the Olympic Games his friend, Michel Bréal, a linguist and historian, reminded him of the story. They devised an endurance race to challenge the resilience and durability of long-distance runners. The marathon would be the last event of the 1896 Olympics and it would recreate Pheidippides’s triumphant odyssey, following the route he took from the modern town of Marathon to the stadium in Athens – a long-distance foot race with symbolism at its heart.

Which meant for one man, the expectation of an entire nation was suddenly heaped on to his slight shoulders. Spyridon Louis probably didn’t appreciate the organisers’ admirable sense of history. Although he had been an amateur athlete of some renown, nobody had before tackled a course of such length. And he, and his fellow runners, were well aware that the ancient legend had ended badly. Pheidippides had dropped dead after delivering his final words: “Rejoice, we conquer.”

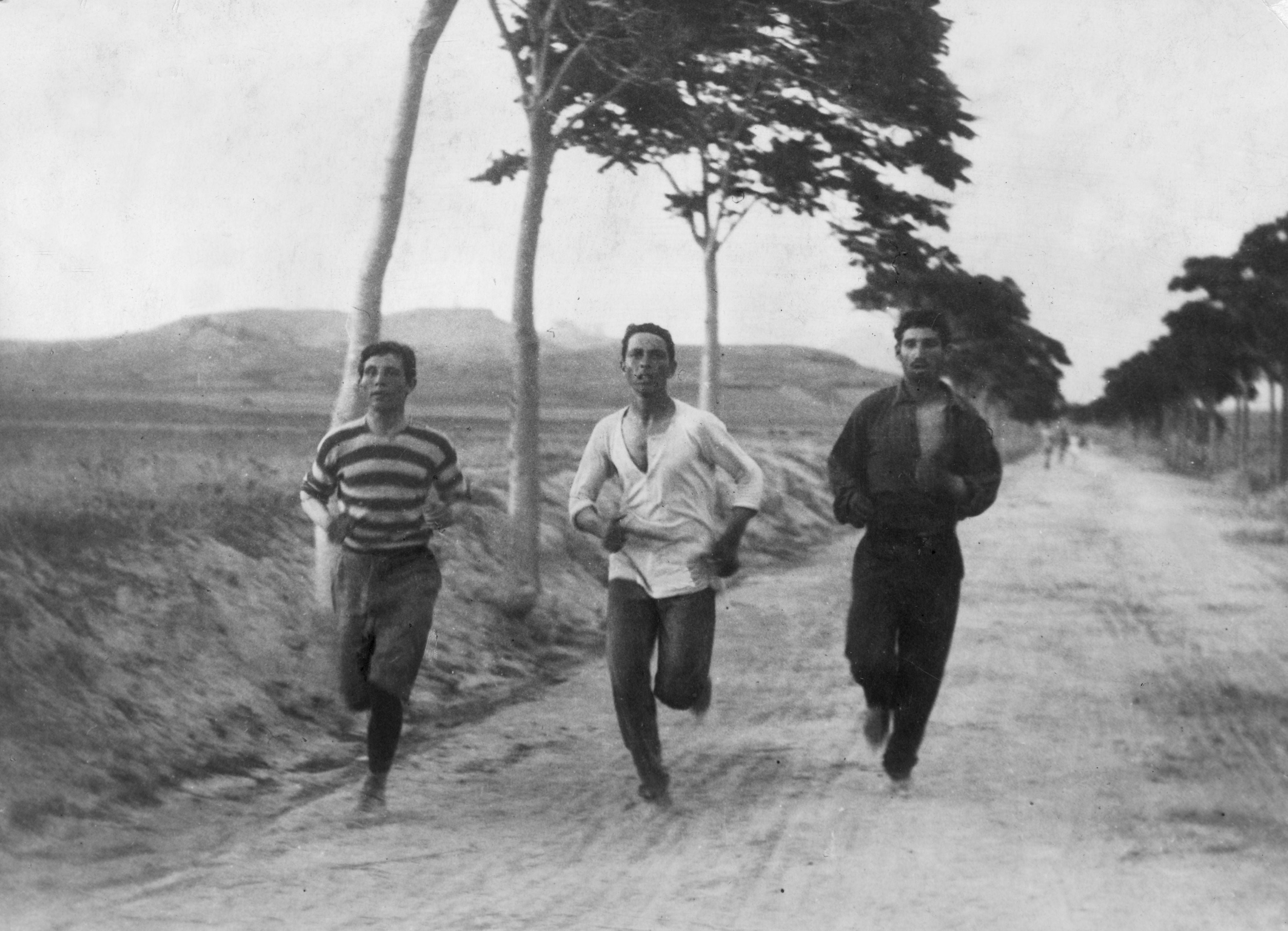

In fact many athletes, backed by medical experts, voiced their concern over the race being run in the stifling middle of the day – rumour had it that three Greek runners had died simply training for the race. And the dry roads were unpaved – the horses of the Greek cavalry accompanying the field kicking up clouds of dust that made breathing difficult. But Louis had been in the army and had since worked as a post office messenger and a water carrier, all occupations that required him to walk or run many miles in the heat every day. His commanding officer in the army had urged him to take up athletics when, after forgetting his sword, he ran 12 miles in under 90 minutes to retrieve it. His stamina and endurance were well known. In trials he had run the race distance in 3 hours 18 minutes and 27 seconds (125 years later, the world record is now 2 hours 1 minute and 39 seconds) one of the fastest times recorded at that point. He knew he had as good a chance as any of the other starters.

They included 12 other Greeks plus numerous well-regarded international runners. Hungarian Gyula Kellner was one of the few non-Greeks who had run the full marathon distance in training for the Games and was considered a potential winner. Edwin Flack of Australia had already taken the Olympic titles at 800 metres and 1500 metres earlier in the games and fancied his chances over the longer distance. Runner-up in the 1500 metres was the American, Arthur Blake, who had an outstanding reputation as a cross-country runner, while Frenchman Albin Lermusiaux was a noted middle-distance track athlete.

The entrants were taken to the start line at Marathon the night before in open carts, but preparation was not ideal. The roads were rutted, jarring the athletes at every turn, causing scrapes and bruises. And it rained. Incessantly. By the time they were introduced to the mayor of Marathon they were soaked through meaning that some, including Louis, possibly overindulged themselves on the local dignitary’s wine. Louis found himself in bed, feeling slightly drunk and being bitten by the bugs that infested the bedrooms of the inn he was billeted in. He slept only fitfully and – orthodox Christian that he was – prayed the rest of the time.

The morning after, he pulled out the whole cooked chicken he’d packed the day before and ate the entire bird as his clothes dried in the sun, washing it down with milk. Then he donned the new lightweight running shoes that the residents of his home village of Maroussi had presented him with. They had pooled their money to give their most vaunted son his shot at fame.

He pinned the number 17 to his vest, lined up under the starting banner and awaited the 2pm gun with 24.85 miles ahead of him (the marathon distance only became standardised at 26 miles 385 yards in London in 1908 when Queen Alexandra, wife of Edward VII, demanded the race finish in front of her royal box). Louis’s tactics were simple, if the other runners disappeared down the road ahead of him, he would only run as fast as the heat allowed. He knew the Greek sun and the Greek roads better than any of them. If they could outlast him then they would deserve their victory, but if not…

Lermusiaux, Flack, Blake and Kellner did as Louis thought they might. The Frenchman was leading comfortably at the halfway point – the village of Pikermi. But he had reached this point in a mere 55 minutes, a pace he couldn’t possibly sustain. Race organisers estimated that he was two miles ahead of Flack. When Louis arrived in Pikermi he was told that the French runner had looked exhausted. Accepting a glass of wine from bystanders he told them “My plan, I think, is working”.

Blake was the first to falter, pulling out of the race around the 75-minute mark. Then Kellner fell back but Lermusiaux was still driving onward, looking increasingly ill at ease but maintaining his lead. Then calamity for the Frenchman. A cyclist following the race wobbled into his path – ironically he was a fellow countryman – and Lermusiaux hit the floor, scraping his knees and hands. After being tended to by a masseur and receiving an alcohol rub-down he rose and continued but had now been overtaken by Flack. At the 20-mile mark Lermusiaux finally collapsed to the ground – his early pace and the collision had taken their toll and he was transferred to hospital, fortunately to recover.

Now Louis was second with the Greeks lining the course screaming his name. “Ambition took hold of me,” he recalled and his pace was reinvigorated. In a show of some arrogance, Flack sent a cyclist on ahead of him to announce his impending victory in the stadium. The Greek crowd fell silent in forlorn resignation. It was a foolish move because Louis had timed his run to perfection. With five miles to go he drew alongside Flack who tried to hang on. But the heat had caused the Australian to dehydrate, he staggered across the road, falling twice before being unable to drag himself to his feet. He began hallucinating as spectators rushed to help, swinging his fists to protect himself from what he perceived to be an assault.

And now Louis was running free, comfortably in the lead and having enough time to accept the plate of oranges his wife held at the roadside as he entered Athens in case he needed sustenance. At the same time his father-in-law was at hand with glass of brandy from the new Metaxa distillery at Piraeus. Shortly afterwards, news that a Greek was leading arrived at the stadium. The Greek flag was run up the pole over the stadium entrance and a cannon fired to announce the arrival of the leader.

It was pandemonium as Louis ran through the gates and into the stadium. “I couldn’t believe the sound,” he said later. “It nearly stopped me in my tracks.” Soldiers pushed back the crowds, flowers and coins rained down on him, a frail figure in a sweat-soaked vest, somehow managing to totter the last few metres to the finishing line, accompanied by two Greek princes Nikolaos and Christoph. Newspaper reports described him as “betraying great fatigue but bearing up well. His face was sunburnt, his white flannels covered with dust, thick drops of perspiration stood on his forehead, but he kept running until he reached the seat of his majesty the king”. As he crossed the finishing line the un-presuming water carrier even remembered to bow.

De Coubertin recalled that “all of Greek antiquity entered the stadium with him”. In later years he would describe Louis’s victory as the greatest moment of all the events he witnessed at that or any other Olympic Games. Louis had run the first sub-three-hour marathon and a nation rejoiced, and heaved a sigh of relief. His fame was assured. Even now Greeks use the idiom “taken off like Louis” to describe somebody who runs quickly.

He would never race competitively again, figuring that nothing could ever come close to what he had achieved that day for himself and his nation. “Flowers rained down, everybody was calling my name, it was a dream. One that cannot be repeated,” he explained. The only time he would appear in public again would be as the carrier of the Greek flag at the 1936 Berlin Games. He returned to his village, eschewing his new fame and the gifts that were being thrust his way.

As well as his winner’s medal, Louis was offered an antique vase from wealthy collector Ionnis Lambros, barrels of wine, 1,000kgs of chocolate, free haircuts and free shoe polishing for life, lamb chops for a year, and the hand in marriage of games benefactor Georgios Averoff’s daughter, alongside a million drachma dowry. Avowed amateur, devout Christian and – fortunately, under the circumstances – happily married man of integrity, Louis declined them all. The only offer he did accept was from King Georgios I. The monarch proffered land, a title, a villa, but Louis turned them all down in favour of a cart, which would help him in his work as a water carrier. The king granted his request and he returned to Maroussi to show the villagers his new cart and the shoes that had taken him to victory.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments