We are creating a new feudalism in this never-ending game of thrones

In one breath we denounce the monarchy, in the next we are voting for a new king or queen of anything – even the jungle. Andy Martin on the stupidity of handing out prizes for being more interesting

Who am I going to vote for? Will it be an insanely wealthy, extremely successful racing car driver, or an insanely wealthy, extremely successful footballer? So hard to choose. I am not, of course, speaking of the general election but of the BBC Sports Personality of the Year contest. And my simple answer is: I won’t be voting at all. I refuse to give someone a prize for their personality. You might as well start handing out prizes for the colour of someone’s eyes or the greatest laugh or the biggest feet in Britain. But, for all I know, perhaps people are flocking to vote for their favourite eyes right now.

Despite all the talk about voter fatigue, the fact is we are addicted to electing our favourites, to ranking everyone, in every field (and even in the outback). It feels as if we cannot live without surrounding ourselves with hierarchies. Feudalism never really went away. Even if we set aside the madly archaic royal family and assorted lords and ladies (and perhaps, let’s face it, they really should be set aside), we can’t get rid of the idea of an immense ladder, with a few occupying the higher rungs and everyone else fighting for space lower down. There is no level playing field, everyone is living on the vertical axis. Even after revolutions and royal executions, our obsession with nobility lives on. We keep on recreating imaginary kings and queens, even if only for a year or a day. And we are now approaching the season not so much of giving as of judging the “Best X or Y of 2019”.

In figures published this week by the Equality Trust the UK’s six richest are richer than the bottom 13.2 million people. It’s Ferraris vs food banks as the Equality Trust’s Dr Wanda Wyporska put it neatly. It used to be the top 10 per cent owned nearly everything. Now it’s more like 1 per cent. And in the Most Unequal Christmas Ever Yet To Come we will have a handful of powerful people owning this planet and others while everyone else is in hock to them. Karl Marx was the first to nail down how wealth accumulates (via “surplus value”).

More recently Thomas Piketty, in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century developed a formula (r > g) to account for the explosion of inequality. And we have at least a few decent politicians scattered about the globe trying to push back against the tide. Quite rightly. But the sad reality is that inequality is not a product of capitalism. Inequality is what we produce on our mental assembly line all day and every day, without even thinking about it. Humanity is hooked on hierarchy. We always have been and we still are.

Call it the “competitive” mentality if you will. Feudalism, or more generally the rise to power of pharaohs, emperors, monarchs, czars, attempted to make sense of an arbitrary coagulation of power by attributing all this manifest asymmetry to a divine order. It had to be like this. Tutankhamun (or Ramses or Henry VIII) was always destined to rule. Such is our desire for ranking that we rolled along with the obvious God-sponsored con.

Feudalism tried to lock inequality in for all time. The pyramid and the palace were the natural emblem of society. But even if pharaohs are now safely mummified, their ghosts live on, floating free from genealogy. Don’t we still have the Premiership Table and the Champions League? Likewise the BBC Sports Personality competition is a form of meta-ranking: you take people who have already won one thing and invite them to win something else. To those who have more shall be given. It’s not a question of economics, it’s more a problem of idolatry.

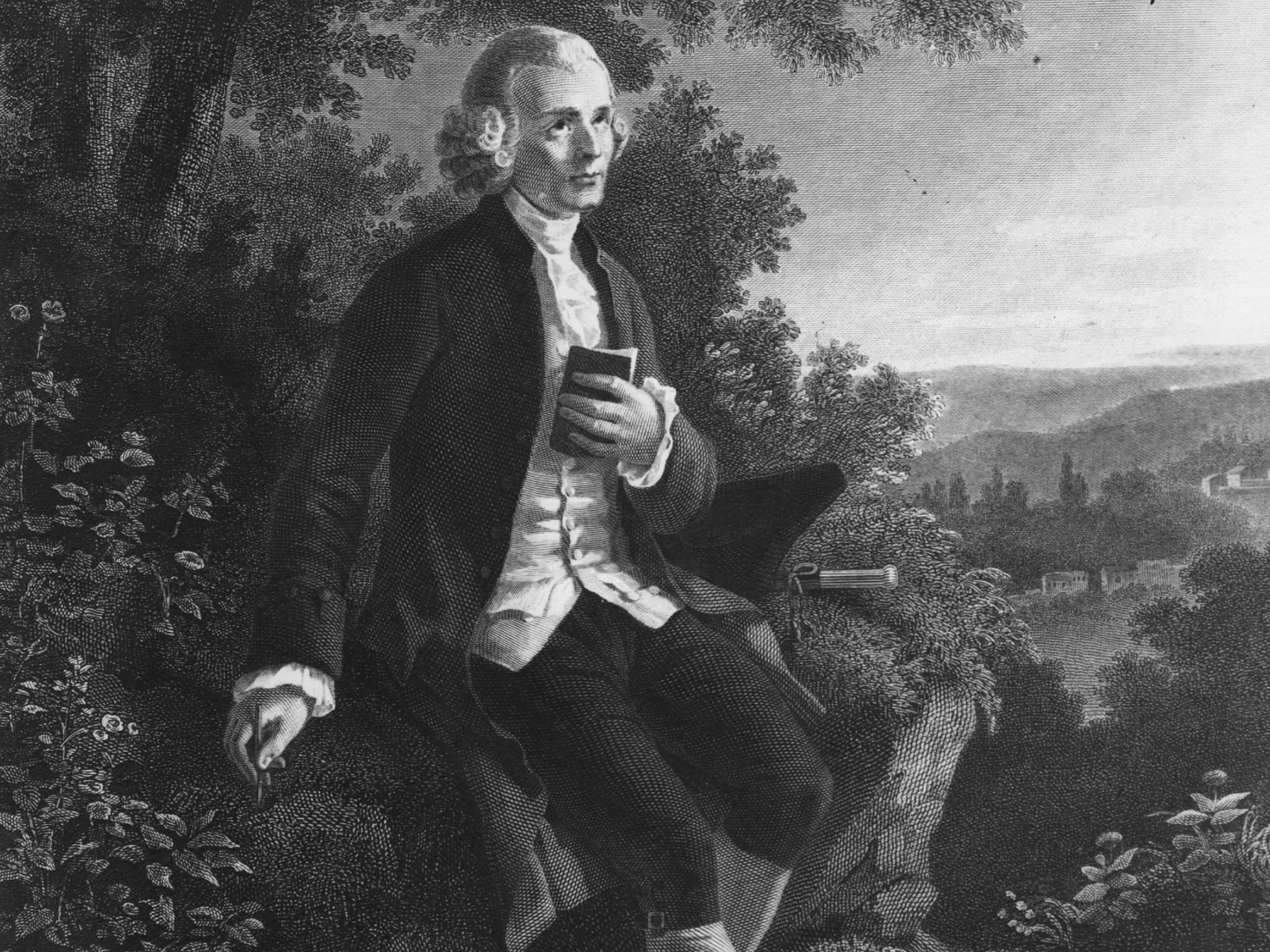

In his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that inequality goes right back to the very formation of society. So long as we were nomadic hunter-gatherers, wandering around in search of the next meal and a mate, nothing was set in stone. The fateful moment occurred when we stopped roaming and started parcelling out the land and the first owner-occupier announced to a disbelieving world, “this is mine.”

And so it began. Frederick Engels in his groundbreaking work on The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State suggests that primitive communism was associated with a matriarchal society and it is only with the rise of patriarchy, when women were divested of their original power, that we see the institution of property rights and increasing hierarchy. The male asserting his superiority over the female begets a society in which everyone is jockeying for position over everyone else.

But there was one development in our history, going back between 100,000 and 200,000 years, that predates all these assertions and statements about who owns what (or whom). Without which it would have been impossible to utter those words about something being mine or yours. Or mine being bigger or better than yours. We could never have made those comparisons stick without having a language in which to express difference.

Rousseau said that the first language was “the cry of nature”. It seems more likely that language was an embryonic feudalism, a system of hierarchy, a way of voting for who gets booted out and who stays in. In the beginning was the Word and the Word was a primal form of the BBC Sports Personality of the Year contest.

The original distinction that our first faltering linguistic steps were designed to consolidate was that between human and non-humans. The eaters and the eaten. Just having a verbal language was in itself a sign of superiority. Language is a construct, a verbal architecture, and therefore automatically against nature. It promotes climate change from the very beginning by assuming the dominion of humankind. The anthropocene starts right here.

The great wellspring of language is the sense that we are better than other species, “every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth” (as Genesis puts it). The concept of being human depends on not being an animal and an animal not being human. Still the first term of abuse that springs to mind if we want to cast aspersions is anything to do with animality. “You animal,” “you dog,” “you pig”, worm, etc.

It’s a put-down because animals are automatically deemed to be inferior, irrespective of their alternate skill sets. We can assume that the poor old Neanderthals were some of the first victims of hate speech. Speech that was readily converted into violence. We were annihilating Neanderthals verbally long before we ever managed to wipe them out. Without language there is no holocaust.

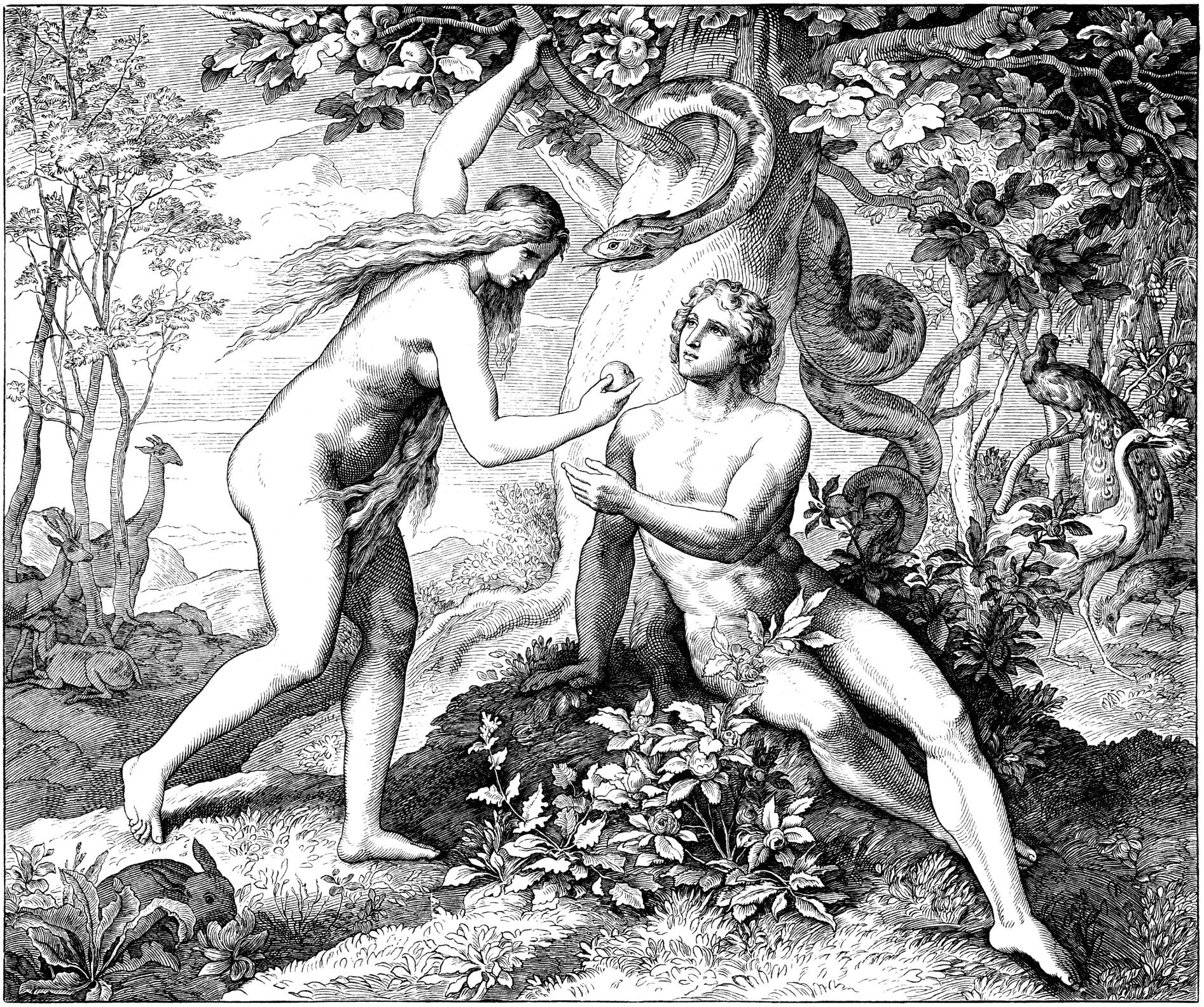

In the Garden of Eden, Yahweh can go about creating all creatures great and small, but he can’t say what they are exactly. That’s our job. “And out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.” God, who doesn’t seem to know what he is doing exactly, is reliant on humans to give names to all the parts of his creation. Otherwise known as “ostensive definition”: we go around pointing and saying, “Look, there goes a hairy mammoth,” or “Watch out, here comes a saber tooth”. We begin with taxonomy, listing and identifying all the occupants of our world, but given the limits of our language we have to group things together into species or clans.

But all this pinning of butterflies to the wall and labelling them was never neutral and purely objective. The notion of a highly discriminatory world order was built in from the beginning. “It is what it is” has become a seemingly incontrovertible catchphrase. But the trouble is that it is so rarely what it is: it is more often suffused with our value judgments. To give one simple example: you’d think East and West could be simple geographical latitudes, but – as Edward Said demonstrated in Orientalism – they are anything but. A place is not a place but a whole network of assumptions and misconceptions. Information is never neutral but coloured with our prejudices. When you mention the East (especially the Middle), Desert Storm and Shock and Awe are never that far behind.

We have more information than ever and it’s ever more laden with bile and bitterness. We exist in order to heap scorn on someone. Perhaps superiority and inferiority are already subtly encoded in binary logic. Are you going to be a numero uno or a 0? There is no in-between state. Division is inescapable. But trolling is not a recent invention.

It is no coincidence that the Greeks came up with the word “barbarian” (to describe the hordes outside the gates who did not speak Greek) and the first Olympics. Racism, nationalism, fascism and the will to power don’t start here, but they are given a decent coat of varnish. The seat of European democracy was also deeply committed to ranking everyone, notably in terms of physical prowess and beauty. It took a philosopher – Socrates – to say it was ok to be ugly. It’s not all about how fast you can run, how high you can jump, or how far you can throw a javelin. All this belongs to the realm of mere appearance, not of truth.

Now it’s all about who wins the Ballon d’or, or who is Personality of the year. These are our non-stop elections. Of course there will always be some who are better at playing football or cricket or baseball than others, but do we have to reward and consolidate inequality? Kurt Vonnegut pointed out (if it needed pointing out) in a dystopian short story exactly how unbearable coercive equality would be: people who could run fast would have to have weights strapped to their ankles and people who could think clearly would be equipped with headphones sending random blasts of thought-scattering static through their ears every few seconds.

But, to speak like an economist, that is to focus on the supply side: it would be like trying to prevent poachers from killing elephants. Which is possible. But it might be more effective to work on the demand side, and try to dissuade people from clamouring for ivory (or rhino horn or any other parts of animals). So too, to come back to the absurd BBC contest, why idolise and bestow honours upon someone for their “personality”? As the Russian poet Yevtushenko once said: “No people are uninteresting.” Do we really need to hand out prizes for being more interesting? It’s like paying hedge fund managers a bonus. They don’t need it. They’ll do what they are doing anyway.

Walter Bagehot, the Victorian political theorist, called the monarchy “the decorative part of the constitution.” It struck me, watching the Prince Andrew interview, that the rug was way more decorative. The royal family has now become redundant, unless they go in for some kind of award show. Most Scandal-Ridden Royal Family of the Year or something. Except perhaps when it comes to proroguing parliament, they have been displaced by all those Top of the Pops celebs and Golden Boot influencers, the grands seigneurs de nos jours.

Meanwhile, in the real elections, we are now voting for the Best Worst. Elections are becoming more like a personality contest. Americans (some of them) voted for the Loudest, Brashest, Most Ignorant, Most Misogynistic, Greatest Narcissist. And Richest. And Superlative-Spouting. What can stop us doing the same? Only the recognition that to vote for a personality is a vote for yet greater inequality.

Andy Martin is the author of With Child: Lee Child and the Readers of Jack Reacher (Polity)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments