The mysterious case of people who burst into flames for no reason

Spontaneous human combustion has been around for 400 years and was especially common at the end of the last century. But despite advances in science, we are no closer to knowing what causes it, writes David Barnett

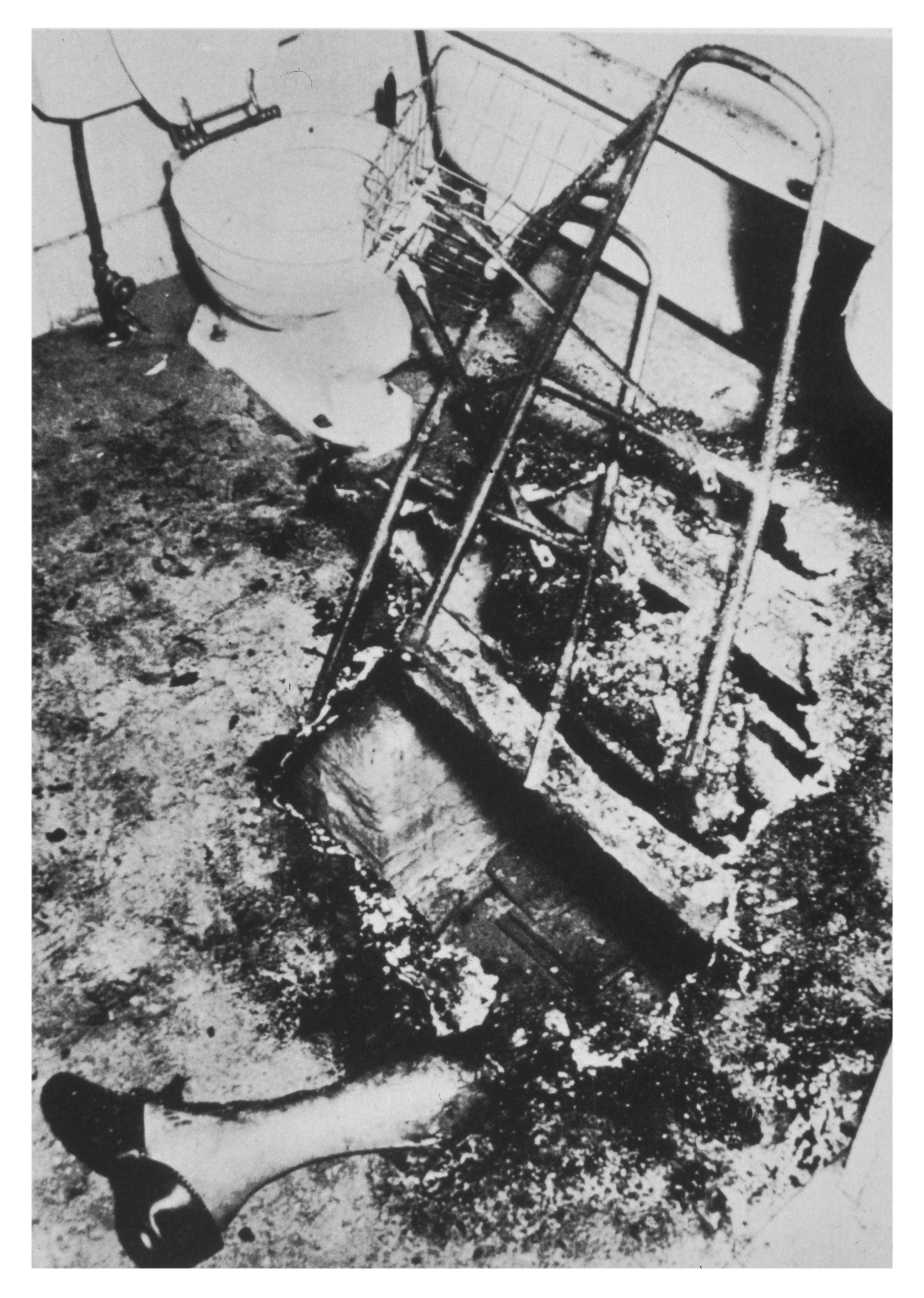

For anyone who lived through the 1970s and 1980s, and was perhaps an inquisitive child of a mildly macabre bent, there will be a photograph that is more than likely seared on their memories. It is a black and white image, and on first glance there’s a certain disconnect about it, a collection of unfamiliar shapes that it’s often difficult to process on initial viewing, possibly because there's nothing comparative to give a sense of scale or location.

It’s only when the eye finally kicks the brain into accepting what it is being shown that the true horror dawns. There’s a twisted grey mass that could be a fire-gutted building in a field or expanse of concrete. But it’s the main focus of the photograph that gives us sudden, rushing context. The field is a carpet, the building is a burned-out chair. And that thing in the foreground is indeed a human leg, charred off just below the knee, and still wearing an incongruously well-shined flat-heeled shoe.

It was, of course, a case of the dreaded spontaneous human combustion (SHC).

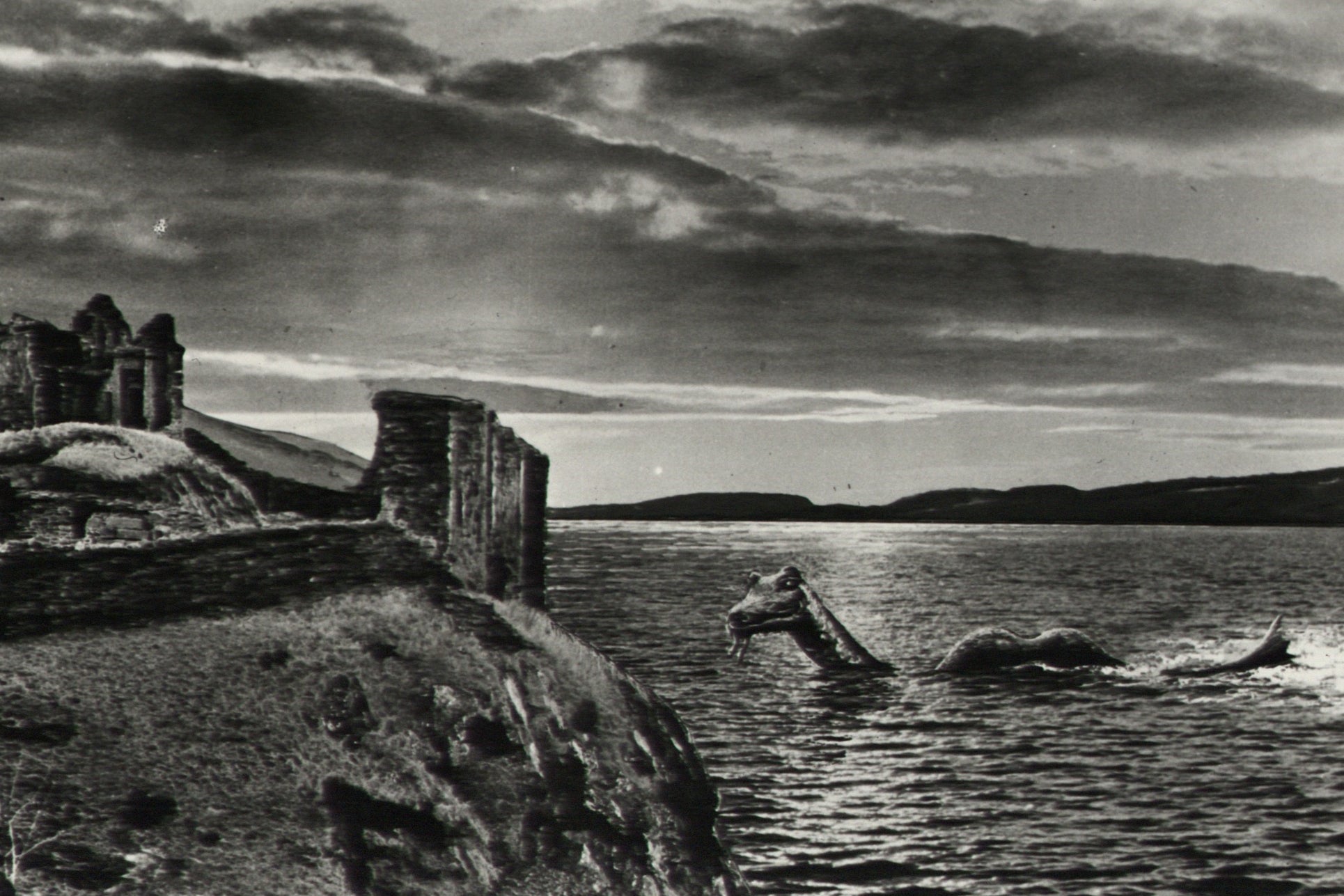

For those of us who read the magazine Unexplained and watched Arthur C Clarke’s Mysterious World, that was a golden age for esoteric and enigmatic phenomenon. With our Zener cards (given free with the aforementioned periodical) we would stare furiously at a picture of wavy lines, willing our dads to allow it to be transmitted directly into their brains when they just wanted to watch World of Sport. We knew what ESP stood for. We were certain the Mayans and the Incas were probably aliens. We were beyond any doubt that if you put a Jammy Dodger inside a homemade cardboard pyramid it would stay fresh for at least a century. Poltergeists were real, as was the Loch Ness Monster, as, of course, was Bigfoot.

The world was teeming with scary things that could not be properly ratified by science. And spontaneous human combustion was the most terrifying one of them all.

Because while Bigfoot and Nessie were unlikely to trouble us, sitting in our suburban homes, you didn’t have to trek off into the wilderness to become a victim of SHC (as it is hereafter designated). All you had to do was sit quietly in a chair, doing nothing in particular, and BOOM. The next thing you knew you were a charred mass of bubbling body fat still wearing your best shoes, just like poor old Mary Reeser, owner of that leg in the photograph that launched a thousand nightmares.

According to my trusty copy of Mysteries of the Unexplained (Reader’s Digest, 1988), SHC is “a well-documented phenomenon in which the human body ignites and burns without any known contact with an external source of fire. In some cases the damage is slight. In others the victim is reduced to ashes. And in some of the strangest cases nearby objects escape relatively unscathed. The chair or bed on which the victim was sitting or lying, and even the clothes on the charred body, may be undamaged or only slightly singed. Often, too, a single foot, a leg or the tips of some fingers remain intact, although the rest of the body is consumed.”

Like Chopper bikes, the colour brown, and disco, SHC was big in the Seventies. But, as with the white dog poo that was equally prevalent at the time, we never hear about it any more. That’s not to say it was purely a thing that happened in the Seventies and Eighties, it’s just that we talked about it a lot then. SHC has a long and illustrious history going back nearly 400 years. But let’s talk about Mary Reeser.

That leg in that dread photograph was once attached to a whole, normal body, that was born in Columbia, Pennsylvania, in 1884. Mary Reeser, nee Hardy, lived a presumably ordinary life for 67 years – at least, public details of that life are fairly scant, it being the end of it that gave Mary her place in the history of the macabre.

Our investigation has turned up nothing that could be singled out as proving, beyond a doubt, what actually happened

On the morning of 2 July 1951, Mary’s landlady went to deliver a telegram to her apartment in St Petersburg, Florida, and, upon taking hold of the door handle, found it strangely warm to the touch. She called the police, who broke into the apartment to find the scene described in that photograph. As well as Mary’s still-shod left leg, there was her backbone and her skull in a pile of ashes.

Aside from her nightmarish legacy in the form of that photograph, Mary’s case is something of a landmark one in the history of SHC because it was really the first time that modern policing and forensics techniques were applied to such a case. Still, despite the technology of the 1950s, police – along with the fire department, pathologists, arson experts and, eventually, the FBI – remained baffled.

A year after the incident, Detective Cass Burgess of the St Petersburg police said in a statement: “Our investigation has turned up nothing that could be singled out as proving, beyond a doubt, what actually happened. The case is still open. We are still as far from establishing any logical cause for the death as we were when we first entered Reeser’s apartment.”

Detective Burgess’s boss, police chief JR Reichert, added to the statement: “As far as logical explanations go, this is one of those things that just couldn’t have happened, but it did. The case is not closed and may never be to the satisfaction of all concerned.”

SHC has been confounding the authorities for a lot longer than that, though. According to Dr Jan Bondeson, a retired university lecturer and author of A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities: A Compendium of the Odd, the Bizarre and the Unexpected, the first documented account of SHC was discussed by the board of the University of Copenhagen in 1635.

Dr Bondeson, who is Swedish by birth but now lives near Edinburgh, describes the case thus: “A scholar had been sitting in a pub drinking strong alcohol and it is said that a flame issued from his mouth with such force as to make speech impossible. Those around him managed to extinguish the flame but he was rather frightened by the incident and decided to walk home, when he suddenly dropped dead.”

The earliest cases were recorded by Danish physician Thomas Bartholin, who, Dr Bonderson says, while a brilliant medical scientist, was also “quite credulous”. But then, much of medicine itself was still in its infancy, and perhaps the idea that a body could be consumed by flames from within was no great leap of the imagination in the 17th century.

Dr Bonderson says that one of the most celebrated early cases of SHC was that involving the Countess di Bandi of Cesena, Italy, in 1731. It bears some relation to the Reeser case, in that the 62-year-old noblewoman was consumed by unexplained flames and only her legs were left amid a pile of ashes. “It does match some of the more recent cases, in that all that was left was a greasy, foul-smelling suit and a moist sticky substance.”

Dr Bondeson has written on unexplained subjects for the Fortean Times, which – inspired by the works and investigations of Charles Fort – has been reporting on esoteric phenomena since 1973. Its archives are a veritable feast of SHC stories from more recent years, often drawn from the pages of the local newspapers.

For example, in April 1985, the Wolverhampton Express and Star reported on the death of Mary Carter, 86, who was found dead in her flat in Birmingham. The cause of death was a heart attack, yet she had burns on her body that could not be explained. In 1979, the York Press reported on an inquest into the death of 76-year-old Lily Smith, whose body had been so badly consumed by fire at her home in Hutton-le-Hole, North Yorkshire, that it was almost impossible to actually identify her. Again, her legs survived the blaze intact. And in 1980, the badly-burned body of a man was found at the wheel of a car parked in a lay-by near Telford, Shropshire. The car was largely undamaged inside.

Common sense tells us that there must be a rational explanation for all of these deaths. The man who died in his car had probably committed suicide, it was suggested in the Birmingham Evening Mail at the time, but exactly how – and why the car wasn’t damaged – is still unknown. In the case of Lily Smith, the fire officer investigating the incident thought it was most likely that something had fallen out of the fireplace, where Smith was sitting, and ignited her clothing. Yet her legs were closest to the fire, and were untouched, and the wooden chair she was sitting on was not damaged. Again, the explanation offered for the death of Mary Carter was that somehow her clothing must have caught fire, but there was no real evidence for that put forward.

According to Dr Bondeson, in the early days of SHC in the 17th and 18th centuries, alcohol use was thought to be a major factor. Many of those who fell victim to it were poor and, thought the medical establishment at the time, imbibing booze would surely have made them more susceptible to burning up. Although the Countess di Bandi was obviously not of the drinking classes, it was said at the time that she had a habit of washing her body in camphorated spirits of wine when she felt under the weather.

If a person started to burn from an external source, even a small one – say a cigarette burn – the body fat could generate enough prolonged heat to destroy bones

“They did believe for a time that it was mainly drunkards who ignited because of the high alcohol levels in the blood,” says Dr Bondeson. “So SHC became an argument in the temperance movement, a warning that if you drank then you could fall victim to it. They had a lot of horror propaganda around it.”

Scientific advances eventually made the idea that drinking could cause you to spontaneously combust unfashionable, but SHC persisted. It even made it into Bleak House by Charles Dickens, in which the villainous, gin-soaked Krook dies gruesomely by said phenomenon. Dickens, who was taken to task by at least one friend and critic for including the fanciful notion in his novel, later added to the introduction of the book a few lines reiterating his belief in SHC, writing: “I shall not abandon the facts until there shall have been considerable spontaneous combustion of the testimony on which human occurrences are usually received.”

With SHC, though, it really is a case of truth being stranger than fiction. Is there really no explanation for it? The most subscribed-to theory, says Dr Bondeson, is that of the Candle Effect, also known as the Wick Effect.

Basically, if a person started to burn from an external source, even a small one – say a cigarette burn – the body fat could generate enough prolonged heat to destroy bones and internal organs, with the clothing acting as a candle wick, absorbing the fat and then burning very slowly until the body is destroyed, apart from, usually, the skull, hands and feet… typically, the areas with less fat. Which could explain why we often get legs left over at the end of an SHC episode.

It certainly sounds more likely than other hypotheses – which, over the years, have included poltergeist activity and ball lightning. In fact, it was suggested as a cause of death for Mary Reeser back in 1951, and was the FBI’s preferred explanation. The renowned anthropologist Wilton M Krogman was called in to look at the case, having pioneered work on fire scene investigation. He disagreed with the Wick Effect explanation, writing a decade later in an article for the University of Pennsylvania: “I find it hard to believe that a human body, once ignited, will literally consume itself – burn itself out, as does a candle wick, guttering in the last residual pool of melted wax. Just what did happen on the night of 1 July 1951, in St Petersburg, Florida? We may never know, though this case still haunts me.”

Just like that picture of Mary Reeser’s leg still haunts many of us. But it’s telling that the most famous case of SHC is almost 70 years old. Surely, given the advances in forensic science, we should have a better idea in the 21st century of what causes it?

Except that you just don’t seem to hear about it any more. Dr Bondeson thinks that’s because while it was once a subject for the mainstream press to pounce on – as evidenced by the cuttings discussed in the Fortean Times and other corners of the esoteric media – it somewhere along the line lost its appeal.

“There were stories mainly in the Seventies and Eighties, and a little into the Nineties, but after that it sort of trailed off, so if there actually are any cases happening, they don’t seem to make it into the press,” he says. “It’s something that used to be discussed in the British Medical Journal, but now it’s something for the Fortean Times only.”

Perhaps there were mundane causes for SHC that societal and lifestyle changes have slowly got rid of. Maybe sitting in front of an open fire in a highly flammable nightie made of man-made fibres was the cause, or falling asleep in bed with a cigarette in your hand. Dodgy three-bar electric fires without the benefit of modern safety certification.

Or perhaps it's just one of those things that will always remain unexplained, one of the mysteries of the universe as yet unsolved by modern science. If so, then the haunting photograph of Mary Reeser serves to remind us that the world is full of strange phenomena… and who knows when SHC might strike again, and to whom …?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments