Spen Valley has always defied convention – this by-election will be no different

The people of Spen Valley have long had a non-conformist streak, religiously and politically, says Mick O'Hare. But that doesn’t make it any easier to predict which way it’ll swing this time

Shortly after the December 2019 general election I was in a restaurant just off Oxford Street in central London. At a table

nearby were two rather loud men. One was, to judge by his accent, Dutch and was bemoaning Brexit. The other was a staunch Leaver. Over the course of the conversation, it became clear the second man worked for the Conservative Party. He was feeding his Dutch colleague the usual spiel of the Leave campaign: the desire of the British nation to be free, untethered to European notions of government – taking back control.

Talk passed onto the just-concluded election. I have no idea who the Conservative was. Pinstripe suit and patrician, he seemed pretty much from central casting. He appeared not to be an MP because he talked of arriving at Tory headquarters as the election results came in, rather than at a constituency count. His dining partner asked him what happened when the exit poll came through and he said this: “We opened up a few bottles of champagne and toasted the gullibility of the northern working class”. The Dutchman seemed taken aback, as indeed was I.

On 1 July the constituency of Batley and Spen goes to the polls in a by-election. It’s entirely possible voters will follow the lead of the people of Hartlepool and elect a Brexit-supporting, Johnsonian Conservative. The combined pro-Brexit vote in Batley and Spen at the 2019 election was greater than that for outgoing Labour MP Tracy Brabin. After significant loss of local industry during the Thatcher years, might it be a case of once bitten twice shy? It seems maybe not.

Rumours (and they are only rumours) suggest that some of the constituency’s voters elected Brabin as West Yorkshire’s first mayor to force the by-election that would allow them to vote for a Conservative MP. The prime minister’s promise to “Get Brexit Done” and “level up” the north has struck a chord. It’s a fascinating conundrum. Boris Johnson’s life is so far removed from the lived experience of most of the people of Spen Valley (indeed from nearly all of us) that we end up perceiving some imprecise universe where Downton Abbey and Bertie Wooster coalesce. But the goal of the PM and his new working class voters still seems the same – maybe the riches promised by Brexit will pour forth. Certainly the whole “lies” and “sleaze” thing is not cutting through beyond those already in the “Anybody But Boris” ranks. But that’s democracy, that’s politics, it’s not a game of absolutes.

I was born in one half of the constituency, the Spen Valley (named after the eponymous river, locally called Spen Beck), in 1964. Brought up in Cleckheaton, its biggest town, and schooled there, primary school holidays were spent walking miles around the area with my maternal grandfather who knew every nook, every cranny, every minuscule jot of local history. Want to know what the George Hotel and Wine Bar on Westgate was once called? It was the Nag’s Head and if you look from the right angle you can still see the scrubbed vestiges of the old sign above the front entrance. It was Cleckheaton’s first pub – owned more recently by New Zealand rugby league international-turned-BBC-pundit Robbie Paul – and in the late 1700s the centre of the then hamlet’s social life. And nearby on Dewsbury Road stood the Marsh Mill whose chimney collapse in 1892 killed 15 workers, all but one of them girls under 16. Panther Motorcycles was founded in Cleckheaton in 1904, performing with renown on both the Western Front and in the Isle of Man TT. All this I learned from my grandfather.

I played youth cricket for Spen Victoria in the Bradford League, (often cited as the nation’s strongest amateur competition), went to cubs in the basement of the imposing Grade II* listed Providence Place Congregational Chapel (a temple to non-conformity described by Pevsner as “amazingly pompous” and which now claims to house the largest Indian restaurant in the UK) and went fishing for the only pike that reputedly lived in the Harry Mann dam. We used to bake parkin (not gingerbread) for bonfire night and stand outside in the freezing cold with a piece of coal at midnight on New Year’s Eve (you’ll have to Google it). And at Christmas we didn’t ice the Christmas cake, we ate it with a slice of Wensleydale cheese (try it, just try it). And yes, we fried fish and chips in beef dripping (still do because that’s the best way) and it was always haddock never cod. Yet if you think it’s all mushy peas and gravy you’re wrong – Pizzeria Aldo’s (with associated prosecco bar) has just celebrated 30 years in Cleckheaton and immigration has left a host of great Indian restaurants. And there’s proper beer in the pubs – my local was (always is?) the Gray Ox in Hartshead. If it isn’t on the map for its beer it should be for its locally sourced food.

Cleckheaton’s park has an impressive war memorial but what I recall most about it from childhood is that it was tended by a gardener who escaped the Spanish Civil War. It’s difficult to comprehend what it must have been like travelling from 1930s Tarragona to soon-to-be wartime Britain, but the culture shock must have been very real. From serrano ham to pork pies (albeit the best pork pies in the country – from Metcalfe’s on Northgate, properly known as stand pies). In my schooldays there were queues down the street when they went on sale. It’s probable there still are. Take that Melton Mowbray.

Like so many regions along the central spine of northern England the Spen Valley lays claim to Robin Hood. Presuming he existed at all, circumstantial evidence suggests he came from nearby Wakefield rather than Nottingham and legend says he fashioned his bows from a dead-but-still-standing yew tree in the churchyard at Hartshead. Robin Hood’s grave in Kirklees Park Estate is likely a Victorian folly, but it is within an arrow’s shot of what remains of Kirklees Priory from whence he was supposed to have fired his final arrow after being bled to death by his cousin, the abbess.

Verifiable history, however, gives the Spen Valley an even greater claim to fame. In 1813, outside the gates of York Castle, 15 Luddites were hanged, the biggest judicial execution for a single crime in British legal history. They were croppers from Liversedge, a collection of hamlets to the south of Cleckheaton, whose cottage industry – using huge shears to crop the surface of cloth until it was smooth – was being replaced by the new factories springing up in the valley. On 11 April 1812 they marched on Cartwright’s Mill, planning to destroy the machinery that was putting them out of work. But their plan was thwarted – the militia was waiting. Two were mortally wounded, the others fled to be rounded up later. The two, Samuel Hartley and John Booth, were taken to the Star Inn in Roberttown, still a pub today (although my grandfather insisted at least one of them was taken to a squat dwelling of the type common in the lower Pennines at the junction of Halifax Road and Windybank Lane, since replaced by a modern house).

Whatever the setting, the denouement was the same. Booth, knowing he was dying and about to undergo amputation of his shattered leg, beckoned local clergyman and anti-Luddite Hammond Roberson, asking him if he could keep a secret. “Yes”, replied Roberson, eager to ingratiate himself with the authorities. “Aye lad,” said the dying Luddite, “so can I.”

As a gesture of civil insurrection the attack arguably superseded the actions of six farmworkers from Tolpuddle who were deported for swearing an oath of loyalty to a trade union 22 years later. You can visit the eponymous Shears Inn where the men plotted the raid and walk the few yards down the road to the only statue to Luddism in the world, erected by the Spen Valley Civic Society. To this day “Luddite” is rarely used in the pejorative in this part of West Yorkshire. It was only after I’d moved away from Spen Valley that I discovered Luddites were, without fail, considered a “bad thing”. The insurrection also provided us with an addition to English idiom. “To come a cropper,” means something bad has happened to you. Like losing your job and being hanged.

The march on the mill was witnessed by Patrick Brontë, father of the famous literary daughters. The family lived in Liversedge on Halifax Road – their house still stands near the Shears Inn and it’s probably the only place in Spen Valley where you might see Japanese tourists – before they moved to their more famous abode in the parsonage at Haworth. Charlotte, however, continued to visit Spen Valley and set parts of her novel Shirley there during the Luddite era. Characters in the book are based on contemporary figures and buildings, such as Red House in Gomersal (called Briarmains in the novel, and now a museum), are still standing. And it’s not just the Brontës leaving a literary legacy. Let it be known that Roger Hargreaves of Mr Men fame was born in Cleckheaton.

Later in the 19th century, the valley was linked to the industrial cities of Leeds and Bradford during the Victorian railway boom and its population began to grow. You can still trace the course of dismantled lines although none of the five stations still exists. What does remain is a crumbling but magnificent cast-iron and stone Grade II listed viaduct which runs from Cleckheaton town centre to the now-demolished Cleckheaton Spen station on the other side of the valley and the site (now a Tesco car park) of the only railway station in the world ever to be stolen. After the line was decommissioned a local scrap dealer removed the buildings of Cleckheaton Central overnight, becoming the only person convicted of pilfering an entire ticket office and waiting room.

To this day ‘Luddite’ is rarely used in the pejorative in this part of West Yorkshire. It was only after I’d moved away from Spen Valley that I discovered Luddites were, without fail, considered a ‘bad thing’

As the industrial revolution morphed into the 20th century the area became renowned for its woollen mills (it’s still known as the Heavy Woollen District) which leads perhaps indirectly to another factor that will play a role in the forthcoming by-election. Overtly or covertly immigration will be on the minds of voters if the constituency’s Leave vote of 60 per cent is much to go by. In the postwar era many people arrived from the Indian subcontinent to work in the once prosperous mills – their culture shock likely as profound as that of the Spanish gardener. Dhesi, Khan and Butt were surnames as common at my comprehensive school as the stout West Riding patronymics of Jowett, Firth and Garside. But unemployment – standing on Halifax Road looking down into the valley last month I could count only two (disused) mill chimneys where once there were perhaps 40 – and latterly Brexit, exposed divisions that many hoped did not exist, as former MP Jo Cox so tragically, and so very briefly, discovered.

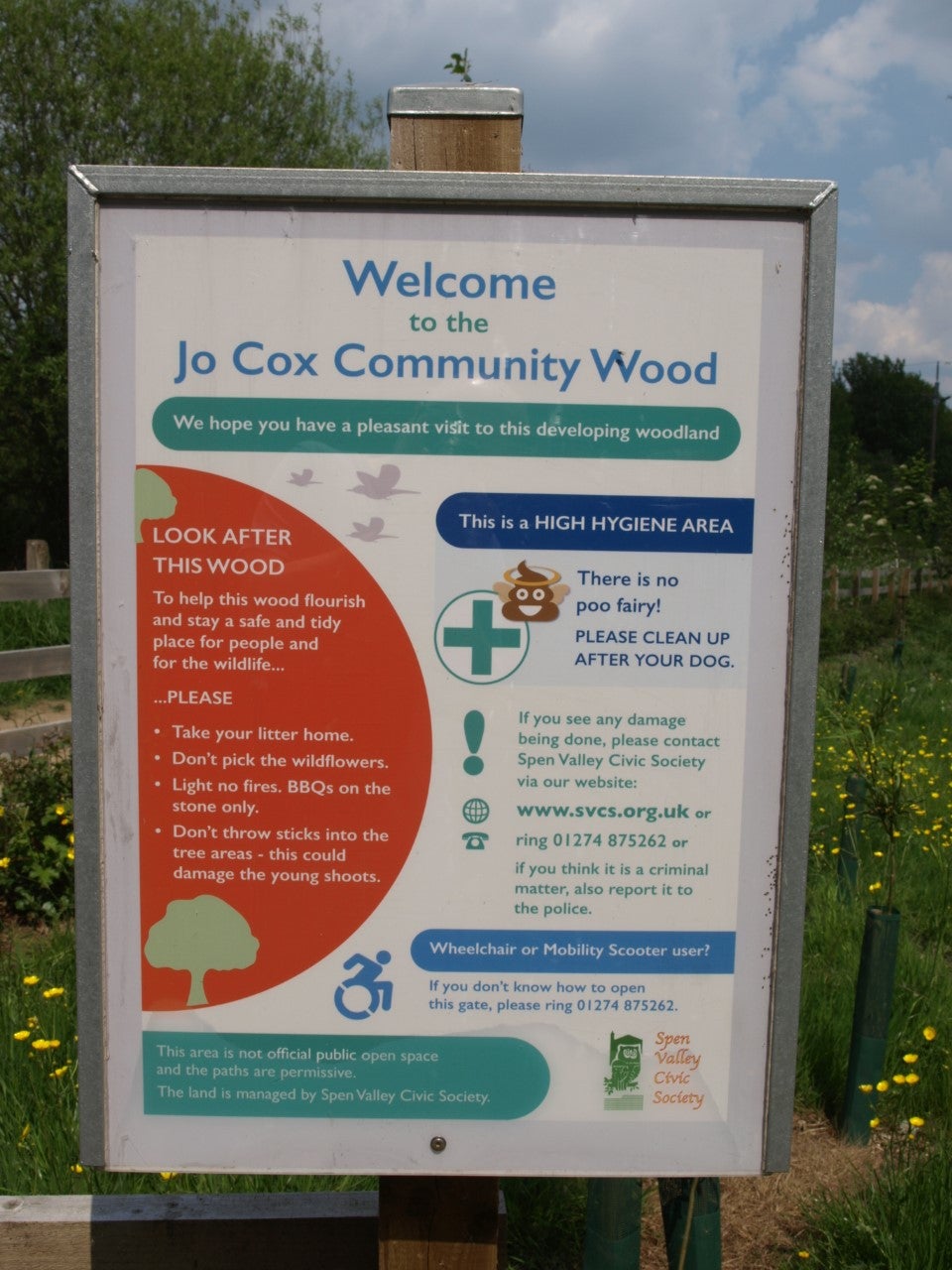

The Jo Cox Community Wood has been planted behind Liversedge Football Club and visiting it prompts thoughts of her oft-repeated maiden Commons speech declaring “we have far more in common with each other than things that divide us” and how it might influence voters’ intentions come election day. Her sister, Kim Leadbeater, is running as Labour Party candidate despite having no previous political experience. But unlike the Conservative candidate Ryan Stephenson she has lived in Batley and Spen all her life. It could make a difference. And while the Reform (formerly Brexit) Party has stepped aside to aid Stephenson’s cause, in 2019 the pro-“clean”-Brexit Heavy Woollen Independent Paul Halloran picked up a substantial vote which damaged the Tories. This may be reaped in part by either the For Britain candidate Anne Marie Waters or Jayda Fransen, former deputy leader of Britain First, although local voters will be aware that “Britain first” were the words used by Jo Cox’s murderer. The pro-regional assembly Yorkshire Party’s Corey Robinson may also nibble into mainstream votes. Of more concern to Leadbeater is the presence of George Galloway, the maverick left-wing defector from Labour who in a 2012 by-election snatched nearby Bradford West from Labour. His Workers Party could split the Labour vote this time around.

I remember the moment I heard of Jo Cox’s assassination and being appalled and incredulous in equal measure. It’s the sort of thing that might happen in Washington DC, maybe? More likely Beirut. But not Birstall, where my dad was born, in the constituency of Batley and Spen.

I love (it’s not too strong a word) my birthplace, from the buildings built on civic pride to the self-deprecating modesty of its inhabitants. Walk the streets of Cleckheaton (it doesn’t take too long) catching glimpses of municipal wealth built on wool, or head into the surrounding hills – their beauty evident even on the bleakest winter day as the rain drives down from the Pennines. If the wind is just right you can hear the bells of Cleckheaton town hall striking the quarter hour. Sit watching the cricket at East Bierley (possibly one of the most idyllic grounds in England) on a summer’s afternoon or at Hartshead Moor (possibly one of the coldest) or gaze out over the valley from the hilltops around Gomersal and quite frankly you can keep the rest of the world.

The area shaped who I was and the person I became. Much as I appreciate my current home, family and the huge metropolis that gave me a living, there is no place on Earth, or indeed beyond, quite like one’s home town. Is it possible to write a panegyric to one’s birthplace without inviting the ire, unintended, of others? Probably not, but the people of Spen Valley are as canny as they are welcoming – in equal parts the perfect amalgam of taciturn and friendly, so maybe they’ll forgive the indulgence. Nobody overreacts, nobody gushes, but equally the community spirit that many say Britain has lost is still clearly evident. And while on the surface some interactions can appear gruff – years ago I visited a schoolfriend and, deciding it would be polite to stand up as his father arrived home, was met with the question: “Have you got piles?” – you are a hundred times more likely to hear “Y’alright love?” as you walk around town. Talking of which, if you want to learn how to annoy a local, question their grammar at your peril. When people say “woh” (rhymes with the first three letters of’ “what”), it's an indistinct “was”, not a grammatically incorrect “were”. The “I were going to York” you possibly heard on that ever-so-funny TV sitcom should actually have been “I woh going to York”. This stuff is important.

The people of Spen Valley have long had a non-conformist streak, not just religiously but politically – in the 18th century Chartism and the General Strike of 1842 which led to the Plug Plot Riots opposing factory wage cuts played their part in shaping local opinion. It’s fair to say the current constituency and its predecessors – a mixture of former industrial towns and rural farms - could never truly be included in what has become known as “the red wall”. In my lifetime it has returned two Conservative MPs, Wilf Proudfoot and Elizabeth Peacock, the latter notoriously defying the whip in a vote on pit closures under John Major’s government. And at local level Cleckheaton itself has frequently returned Liberal Democrat councillors.

In fact so non-conformist is the valley that when the great rugby schism of 1895 struck the world of Victorian sport and rugby clubs in the towns and cities surrounding Spen began switching wholesale to professional rugby league, Cleckheaton’s club never did. The town stayed amateur and still has a rugby union club in an area synonymous with the other rugby code. Jeff Butterfield captained England in the 1950s and toured with the British Lions. Even the comprehensive I attended, Whitcliffe Mount, played rugby union. That really is a big deal in these parts, indicative of either deep consideration or bloody-mindedness (or both), and perhaps goes some way to explaining why the constituency cannot be so easily politically categorised.

But of course, for an exile like myself, there is a truism behind all this that can’t be avoided: once a Yorkshireman always a Yorkshireman, accepting all the positive and negative connotations that confers. And for what it’s worth people of the Spen Valley consider themselves real Yorkshire, not like people in Sheffield (practically Derbyshire), Middlesborough (Geordies) or Hull (Dutch). One always runs the risk when discussing one’s origins and the nature of one’s work of sounding like Victoria Wood’s caricature northern playwright played by Jim Broadbent, overflowing with excruciating passion: “Alan Hammond. Yorkshireman. Writer… my pen’s my scalpel. I’m a panel beater hammering sentences into shape. The north, I love it, I feel passionately about it, they are choking it to death… they are killing it…” On the verge of tears he adds pitifully: “My north…” Naturally he lives in Chiswick. Nowt worse than a professional Yorkshireman.

So as somebody whose home is now in north-west London it ill behoves me to pass an opinion on how voters from my home town should exercise their franchise 35 years after I upped sticks and left. And while the independent-minded citizens of the Spen Valley will most definitely not heed the utterances of a Remoaner from the media who left to live, work and marry in “bloody London” (and nor should they) maybe it’s worth pondering instead the words of the gentleman in the London restaurant. What on earth could he have been implying, this man from the party promising to “level-up” Britain? A throwaway line from an underling offering a personal opinion? Tongue in cheek? Or worse? I honestly don’t know.

If your persuasion is that whatever it was it has little bearing on you as a constituent of Batley and Spen well, it is, to use an unwitting phrase, a free country. One person, one vote. The valley has defied convention in the past and will likely continue to do so. Which convention is defied this time around, we will discover very soon.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments