How the capture of a tiny South Atlantic island triggered the Falklands war

The 1982 invasion of the Falklands had a prelude played out 800 miles away, writes Mick O’Hare, who speaks to royal marines who clashed with Argentinian forces on rain-soaked South Georgia

When, in 1915, Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance became trapped and then crushed in the Antarctic ice, he embarked on one of humanity’s greatest quests for survival. The following April, leaving his men in makeshift camps on Elephant Island, he and five others crossed the perilous Southern Ocean into the South Atlantic aboard what was little more than a rowing boat. Travelling an astonishing 800 miles to make landfall on the southern coast of South Georgia, they crossed the island’s treacherous mountain terrain to reach help at the Stromness whaling station. They all survived and every man on Elephant Island was rescued.

Despite its name, South Georgia is a remote 100-mile long island in the South Atlantic, nearly 1,700 miles east of the South American continent – a proverbial needle in a very wet, very cold haystack. But Shackleton got his men there. And what they found was pretty much how it looked a full 65 years later when Constantino Davidoff, an Argentine scrap-metal merchant, turned up there in December 1981.

“Penguins, wind and incessant rain,” was how Stephen Martin, commander of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) on South Georgia at the time described it. To call it inhospitable doesn’t really do it justice. The island has had no permanent population since the last whaling station at Grytviken closed in 1965 although the BAS has summer stations at Leith Harbour and Grytviken. South Georgia has been ostensibly British since seafarer and explorer James Cook claimed the island in 1775 – it even has a British postcode SIQQ 1XX – although in 1927 Argentina made its first claim to the islands, one it repeated regularly thereafter.

Davidoff’s visit in December had raised eyebrows at the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Although Davidoff had signed a contract with British company Christian Salvesen to scrap one of South Georgia’s old whaling stations he hadn’t fulfilled the stipulation to inform the BAS at Grytviken. The British protested, Davidoff personally apologised to the British embassy in Buenos Aires and agreed to return the following March. But Davidoff was about to become a stooge for his government.

Its president, General Leopoldo Galtieri, was facing growing opposition, his military dictatorship in turmoil. The Argentine economy was floundering – inflation was running at 600 per cent while real wages had fallen by 20 per cent. The public, already suffering under the repressive regime which had killed thousands of political opponents and imprisoned many more in what became known as the dirty war, was becoming increasingly restless. Trade unions were demanding a general strike.

Galtieri resorted to the tried-and-tested method of despots desperate to curry favour with a dispirited public, one that we are still seeing played out in 2022 on the eastern fringes of Europe. He appealed to nationalistic sentiments. It was time to start a war; one he figured he couldn’t possibly lose. Galtieri set his sights on invading the British-administered Falkland Islands – known as the Malvinas in Argentina – 950 miles off the Argentine coast and over which his nation had long made claims. He convinced himself that the British would not be up for the fight. It was a crucial misinterpretation. Discussions between the two nations over sovereignty of the Falklands had recently ebbed but not because, as Galtieri presumed, the British had no interest. In fact, the converse was true. Sovereignty was not being discussed by the UK because it had no intention of ceding the islands.

Galtieri gambled that Britain would see recovering the islands, nearly 8,000 miles from London, as too expensive and too dangerous and was aware that Britain had recently reduced its military presence on the Falklands. He believed his nation would reward him with a decade or more of power if the Argentine flag was flying over Falklands capital Port Stanley.

As the 40th anniversary of the battle for the Falklands approaches much will be made of the invasion and the subsequent despatching of the royal naval task force to reclaim the islands. The battles at Goose Green and San Carlos, the bombing of Port Stanley airfield and the sinkings of Argentine cruiser General Belgrano and the destroyer HMS Sheffield, among others, will be retold in great detail.

HMS Endurance, under the captaincy of Nick Barker, was despatched from the Falklands on 21 March with the intention of expelling the Argentine force

But the invasion of the Falklands themselves had a prelude played out 800 miles to the east and at the centre of which Constantino Davidoff suddenly found himself. Davidoff was visited by Admiral Edgardo Otero, a confidant of Admiral Juan Lombardo who had been instructed by Galtieri to draw up plans for the invasion of the Falklands and Jorge Anaya, the naval advisor to the president. To distract the British, Otero wanted to annex South Georgia, drawing attention away from the main invasion force

Davidoff was unhappy with his fait accompli. His had been a genuine business deal that he hoped would make money, but instead he would lose his livelihood and, in the eyes of some, he was inadvertently guilty of provoking a war. Years later he would tell the BBC “I lost everything – my planes, my boats and my company. It left me a sick man. I couldn’t even support my family.”

At the time though, he had little choice. Davidoff’s return journey to South Georgia in March aboard the Bahia Buen Suceso would be carrying extra crew members in the form of undercover Argentine marines posing as civilian scientists. The mission was codenamed Operation Alpha. The war in the South Atlantic had begun.

This time Davidoff deliberately failed to inform the BAS but his landing on 19 March at Leith harbour was spotted by a BAS party who reported that men in military uniform were present, rifle volleys had been fired into the air and the Argentine flag was flying. The landing party had also broken into the BAS station at Leith, defaced British signs and stolen emergency rations.

The Foreign Office demanded removal of the flag and insisted that Davidoff and the Bahia Buen Suceso’s captain and crew report to Stephen Martin at Grytviken. Although Captain Briatore insisted he had the approval of the British embassy in Buenos Aires that was denied by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. “Trying it on, probably,” said Martin. Briatore departed leaving behind a party of marines under the command of “the Blond Angel of Death”, Lieutenant Commander Alfredo Astiz, a man already wanted in several countries following the disappearance of European citizens during the dirty war.

HMS Endurance, under the captaincy of Nick Barker, was despatched from the Falklands on 21 March with the intention of expelling the Argentine force. It carried 22 Royal Marines, led by 22-year-old Lieutenant Keith Mills, and two helicopters. The diversionary tactic to draw defences away from the Falklands appeared to be working. Two days later Endurance arrived at Leith where it found a second Argentine ship the Bahia Paraiso under the command of Cesar Trombetta which had landed more marines, unloaded supplies and was carrying two helicopters.

Barker was pretty certain he knew what the Argentine navy was up to. Endurance had spent years in the South Atlantic and regularly visited ports in both Chile and Argentina. Chilean naval officers had often told him about Argentina’s designs on the Falklands. In fact a senior Argentine naval officer had admitted it in person only a couple of months before. “There’s to be a war against the Malvinas. I don't know when, but soon,” Barker was told. He reported everything to London but received little acknowledgement. “I even offered to try to defuse the situation by meeting Trombetta but they just suggested we hold station.”

Yet here was first-hand evidence. Nonetheless, the British still seemed keen to avoid confrontation; Endurance was instructed to hold a watching brief. British foreign secretary Lord Carrington proposed to his Argentine opposite number Nicanor Costa Mendez that the Argentines have their passports stamped at Grytviken to give them temporary permission to stay. But Mendez refused on the grounds that Argentina’s claim to the islands was still unresolved. His reaction seemed to suggest conflict was unavoidable.

The Royal Marines set up an observation post above Leith but still did not challenge the Argentines. The Argentines spotted the British, overflew their positions making what were described as “age-old rude gestures” and returned to the Bahia Paraiso which then headed into the South Atlantic. HMS Endurance was instructed to follow. It was a ruse to draw the British away from South Georgia. By now the astute but frustrated Barker was convinced it was all a diversionary tactic – “buggering us about” was how he later described it – and an invasion of the Falklands was imminent. This time the Admiralty paid him due notice, asked him to deposit his contingent of Royal Marines on South Georgia and prepare to return to the Falklands. “We knew the fight was coming. I wasn’t happy being caught between South Georgia and the Falklands,” recalls Barker. “I was agitated. I’d seen it coming.”

The royal marines defence held firm as a second helicopter arrived with reinforcements on the other side of Shackleton House

On inflatable boats the Royal Marines hastened to the BAS base at Grytviken under instructions from London that they should make only token resistance to any Argentine aggression. Mills, possibly apocryphally, replied: “Sod that, I’ll make their eyes water.” Meanwhile, a further Argentine ship, the frigate Guerrico, carrying more helicopters, arrived off South Georgia with additional marines bringing the Argentine force close to 100 men. Both the Guerrico and the Bahia Paraiso headed for Grytviken where the marines had started to dig in and fortify the BAS base at Shackleton House. Meanwhile, three royal marines were despatched to protect two British wildlife photographers, Cindy Buxton and Annie Price at St Andrews Bay who were unaware of what was unfolding on an island where they had expected to meet hardly anybody, let alone find themselves at the centre of an international incident. “You set off to photograph seabirds and end up being seconded to the navy,” says Price.

Martin, to no surprise on his part, was proved correct. On 2 April as Endurance prepared to return to the Falklands, Argentina launched its invasion of the islands. The Royal Marines at Grytviken heard the news on their radios. That same day Astiz and Trombetta informed their men that they would launch Operation Georgias, an assault on Grytviken. The weather, however, was squally leading Astiz to delay his assault for 24 hours. Mills, still under orders to only “fire in self defence after issuing warnings” and to “not resist beyond the point where lives might be lost to no avail” instructed his men to fortify the beach at Grytviken with wire, landmines and an improvised bomb under the jetty made from a 45-gallon oil drum filled with petrol and paint. The BAS commander Martin also exhorted Mills not to risk the lives of his soldiers.

At 10.30am on 3 April, the Argentine force arrived. Trombetta – according to some reports convinced that only BAS personnel, and not Royal Marines, were holding out at Grytviken – demanded the British capitulate, announcing that Rex Hunt, the governor of the Falklands Islands, had surrendered and thus South Georgia had already been ceded to Argentina. Mills was informed by Endurance that this was untrue. The Falklands government had indeed surrendered but it had no bearing on the situation in South Georgia.

An hour later, as Mills and his team awaited what they expected to be a delegation at the jetty, an Argentine helicopter landed near Shackleton House. As they watched they saw Argentine marines raise their weapons. They waited no longer and sprinted for cover. “To be honest, I didn’t think we’d be alive the following morning,” says Lance Corporal George Thomsen. “We’d been dropped in the s*** a bit. The numbers were pretty overwhelming and I thought if we killed any of their men they’d take revenge.” But the Royal Marines defence held firm as a second helicopter arrived with reinforcements on the other side of Shackleton House. As they took to their hastily dug trenches astonishingly a single burst of British machine-gun fire, the first of the conflict, managed to damage the second helicopter. It was followed by a hail of British bullets. With smoke pouring from its engine the pilot flew it back across the bay, only to crash and roll before it could reach the safety of its ship. Two men died and four were severely injured. “It allowed us to hold out for longer than we expected,” recalls Thomsen.

Without their reinforcements the first contingent of Argentine soldiers was pinned down in outbuildings by British gunfire. Their commanding officer called on the Guerrico to provide cover. Advancing into the cove near Grytviken beach Guerrico opened fire but its guns jammed and it became trapped in the narrow inlet. “It came in so slowly,” says marine Steve Chubb. “I looked huge and when the gun swung round to point at our positions it looked like it was pointing straight at me. You feel very vulnerable.” The British returned fire with anti-tank rockets and, in Mills’s words “everything else we had”. Marine David Combes fired the decisive shot. The projectile from his anti-tank weapon skimmed the water and struck Guerrico just above the waterline.

An Argentine sailor was killed and the ship’s weapons damaged. Taking on water and listing at 30-degrees the corvette retreated. It was quite the coup for what was an effectively lightly armed force. Unfortunately for the British though, the Guerrico’s retreat meant it could use its undamaged long-range gun to pound their positions.

For two hours heavy fire was exchanged between both sides. Mills had hoped to hold out until nightfall and then head north across the island, fighting guerrilla warfare and keeping the invaders on their toes. However, when one of his men, corporal Nigel Peters, was struck twice by Argentine bullets, more Argentine marines were disembarked and the Guerrico’s shells began to rain down, Mills knew risking the lives of his men further would be futile. He had achieved his aim of forcing the Argentines to use force and thus putting themselves at odds with international law.

At 12.48pm and under protest from his Sergeant Peter Leach and from Thomsen who wanted to fight on, Mills picked up a white coat and, waving it, approached the Argentine attackers, offering ceasefire on his terms otherwise fighting would continue. “At first I was furious,” says Thomsen. “I was the last to lay down my weapon, but in hindsight Keith handled it so well with no loss of face, and he was very brave.”

Margaret Thatcher declared that she would not see the Falkland islanders living under the Argentine ‘jackboot’

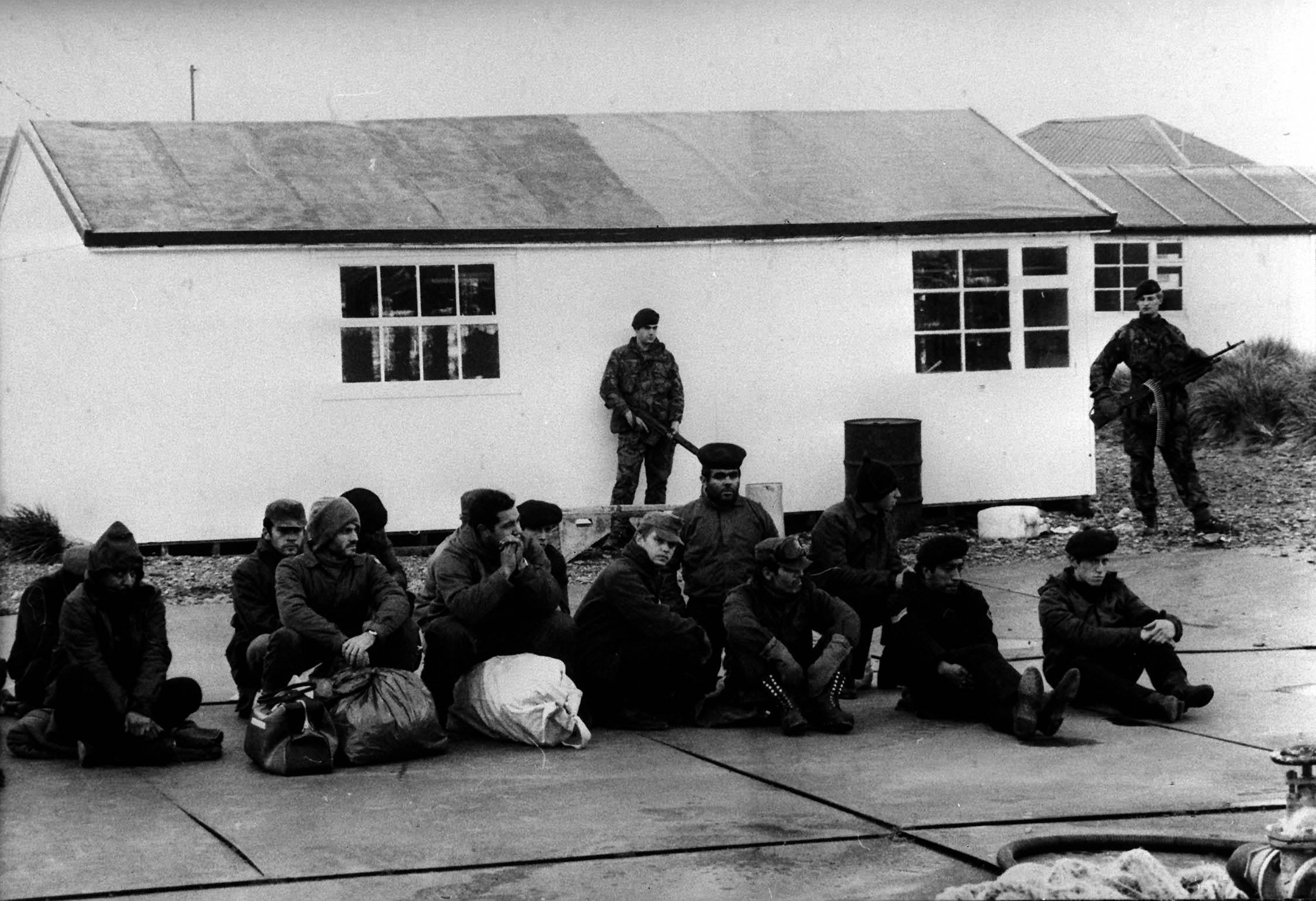

When the 22 Royal Marines came forward at first Astiz wanted to know where the remainder were, seemingly astounded that so few men had put up such stout defence. The Argentines collected their dead and the British were taken into custody by Astiz alongside the BAS team. The two wildlife photographers – and 13 other BAS scientists undiscovered by the Argentines – remained, continuing their work although when they were finally evacuated by the British after they retook the island, Price handed over a pistol the marines had shown her how to use. “I hope I would have had the nerve to use it,” she later said. Both the Falklands and South Georgia were under Argentine occupation.

The eventual outcome of the conflict is well known. The British did not react as Galtieri had hoped. British prime minister Margaret Thatcher declared that she would not see the islanders living under the Argentine “jackboot”. To pretty much universal political and public accord in the UK, the Royal Navy task force sailed for the South Atlantic on 5 April, just three days after the invasion and, after the loss of 255 British and 649 Argentine troops, the Falklands Islands were retaken on 14 June. Fifty days earlier South Georgia had also been recaptured following Operation Paraquet, capturing 155 Argentine soldiers and killing one. In one of the campaign’s most publicised pronouncements Task Group Commander Captain Brian Young radioed the Admiralty: “Be pleased to inform Her Majesty that the White Ensign flies alongside the Union Jack in South Georgia. God Save the Queen”. “The Empire Strikes Back”, wrote American magazine Newsweek. “The last gasp of colonialism,” wrote the less charitable Boston Globe.

Whether that was a fair assessment or whether there was a greater principle at stake is moot. The right to self-determination is enshrined in Article 1 of the United Nations Charter of 1945 and Britain insisted on behalf of the Falkland islanders that the invasion had clearly violated this principle. It was an assertion generally accepted by the UN especially after the British government said it was still prepared to enter into diplomatic discussions. However, that suggestion was rejected outright by the Argentine junta who were buoyed by the huge popular support the invasion initially garnered at home. Backing for their position was limited to a handful of South American states. Then, as now, invasion of a defenceless outpost of a sovereign democracy by a military dictatorship was one very few nations were prepared to support. The UN came down in favour of the British position. On 3 April, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 502, calling for the withdrawal of Argentine troops and a cessation of hostilities.

The Soviet Union chose not to invoke its veto as a permanent member of the UN Security Council because it viewed both Britain (as a Nato member) and Argentina (as a right-wing dictatorship) as natural enemies. Ironically as a member of the European Community – the forerunner to the European Union – Britain had the full backing of member states with British defence secretary John Nott declaring that French president Francois Mitterrand’s nation “was our greatest ally”. One can only imagine how much Brexit might have altered that assertion if the conflict arose today.

Unlike the European Community, the United States had been ostensibly neutral over the issue prior to the invasion. Eventually it imposed sanctions on the Galtieri regime, while simultaneously hoping not to damage its interests in either Nato or South America, but the US administration remained somewhat perplexed by the conflict. President Ronald Reagan asked why two allies of his country were scrapping over a “little ice-cold bunch of land down there”. Opponents of further American intervention insisted that by helping the British the US would have violated its own Monroe Doctrine which opposed European involvement in the affairs of the Americas. Nonetheless Reagan and his secretary of defence Caspar Weinberger were later awarded honorary knighthoods which rather gave credence to the belief in diplomatic circles that they had helped the UK beyond their public declarations.

Of the South American nations, some supported the Argentine position but only Peru provided military assistance to Argentina, although it was also offered by Cuba and Bolivia. Chile, conversely, was in full support of Britain – a consequence of long-running military disputes with Argentina and the Argentine threat to annex its Beagle Channel islands once victory in the Falklands was complete. While Thatcher praised Chile for offering assistance to Britain it left her open to claims of colluding with its despotic ruler Augusto Pinochet, himself no stranger to ordering the imprisonment and execution of political opponents. When Pinochet was arrested in the UK 16 years later on a warrant from a Spanish magistrate over human rights violations in his own country, the British government saw fit to free him. Whether this was payback for his involvement in 1982 is questionable, but some in the international community viewed it as such.

The international ramifications of the conflict still rumble on today. But what of the smaller and more personal legacies of the battle for South Georgia?

The Royal Marines who were held captive have since reported that because of the considerate way they were treated after capture, a mutual respect grew between the two groups. “I actually think they were scared of us once they discovered there were only 22 of us,” says Thomsen. Another of the British soldiers Andrew Lee has written: “They bore us no malice,” this despite three of their comrades being killed by the British defenders. “They understood the job we did. They were marines, like ourselves.” The injured Peters was treated by Argentine doctors and the Royal Marines and other prisoners were actually returned to Britain via Uruguay before the conclusion of the Falklands War – one of Mills’s terms of surrender – and in an incongruous twist of fate Mills and his men returned to South Georgia to guard Astiz and the other Argentine prisoners of war after 25 April.

Lee’s comrade Michael Poole, instrumental in shooting down the Argentine helicopter, later sought reconciliation. Ten years ago he contacted Víctor Ibanez who had fought against him on that day. They have become firm friends. “We knew how to accept the role each one played,” explained Poole in 2013.

It’s not jingoistic to make the point that a certain amount of courage was required by the 22 royal marines to hold out against insurmountable odds of pretty much 50-1

Mills was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, as was the commander of HMS Endurance’s helicopters John Ellerbeck. Leach, Mills’s sergeant, was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. Barker received the CBE. On the Argentine side, principle corporal Francisco Solano Paez won his nation’s Valor en Combate.

And what of Davidoff, the inadvertent architect of the invasion? He realised that the contract he had with the British government would never be fulfilled. In later years he insisted that only his workers had accompanied him back to South Georgia and there was no military presence, although the evidence suggests otherwise. This was most likely a ruse to aid him in an attempt to sue the British government for not allowing him to fulfil his contract. He was unsuccessful, and the Argentine government too, would not compensate him. He blamed Britain for sending marines to solve what was essentially a civilian matter. “I have sympathy for Davidoff who was caught up in Argentine government machinations,” Mills told the BBC. “But he is fooling no one. It’s at worst a lie, at best self-delusion. It was a military occupation of a British territory.”

South Georgia ceased to be administered by the Falkland Islands in 1985 and is now a British Overseas Territory, part of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands chain. Argentina’s claim on South Georgia today, like that of the Falklands, is still extant and is an article of the Argentine constitution.

The rights and wrongs of the conflict were aired at the time and in diplomatic negotiations since. Was Britain a declining colonial power determined to hang onto the last vestiges of empire? Was Argentina asserting its rights to territory in its vicinity, territory that it had long disputed was its alone? What can be certain is that the successful recapture of the Falklands and South Georgia by the Royal Naval task force bolstered – if not indeed, saved – Margaret Thatcher’s premiership, and led to the downfall of Galtieri’s and, perhaps serendipitously, the eventual reestablishment of democracy in Argentina, almost certainly not Galtieri’s intention.

It’s not jingoistic to make the point that a certain amount of courage was required by the 22 Royal Marines to hold out against insurmountable odds of pretty much 50-1 if the Argentine ships’ contingents are taken into account, in order to protect a piece of rock on which nobody lived permanently. Bravery is not a function of necessity. Diplomats can argue over the rights or wrongs of the varying claims to the world’s landmasses, but the soldiers who took part in the conflict 40 years ago this week, of both sides, were simply carrying out the orders of their governments to the best of their abilities.

Today, apart from the BAS, the island’s only visitors tend to be cruise ships visiting the graves of Shackleton and his second-in-command Frank Wild. By incredible coincidence and no lack of irony, Shackleton would die on a later mission while anchored in King Edward Cove, South Georgia. He was buried in Grytviken graveyard on the island that had proved to be his salvation only six years earlier.

The penguins, the rain and the grey skies all still make their presence felt on the barren, mountainous terrain. Its inhospitality means those few visitors it receives frequently question why anybody might want to fight over who owns it. Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges described the conflict as pointless. “Two bald men fighting over a comb,” he wrote. It’s possible he never consulted those who were present on South Georgia on 3 April 1982.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments