The people’s occupation of Seattle could see the birth of a very different America

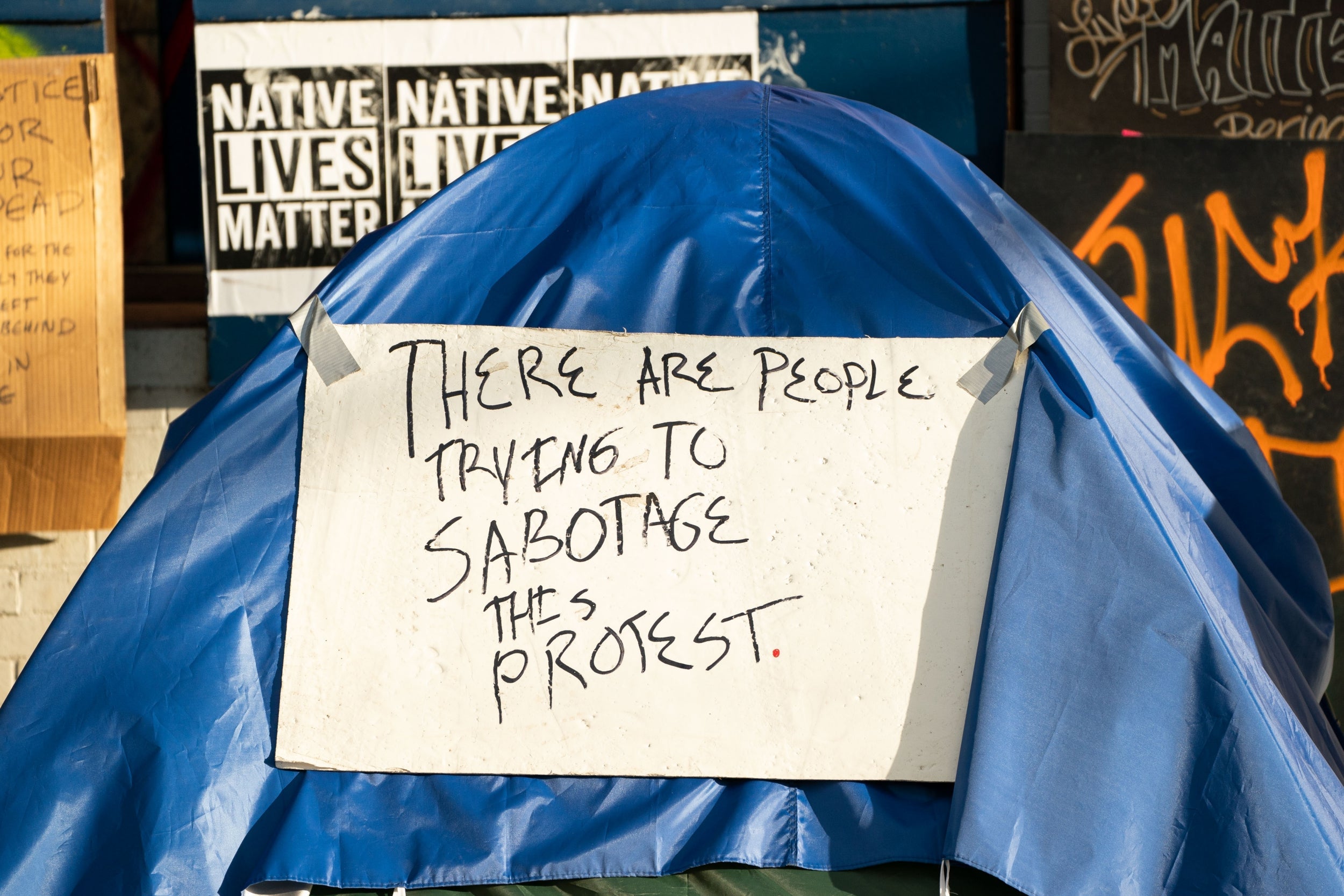

There is an image being created of the Black Lives Matter ‘seizure’ of Seattle; one of anarchy, crime and a ‘summer of love’. But, writes Holly Baxter, the reality is far more nuanced and mundane than that

Does anyone notice how little the Radical Left takeover of Seattle is being discussed in the Fake News Media? That is very much on purpose because they know how badly this weakness & ineptitude play politically. The Mayor & Governor should be ashamed of themselves. Easily fixed!” So tweeted Donald Trump a few weeks ago, after he became aware of a Seattle neighbourhood called Capitol Hill being run by protesters and seemingly abandoned by police.

A group of “domestic terrorists” and “rapper-turned-warlord” types had taken over, added Fox News. “Summer of love,” wrote one tweeter sarcastically, sharing a video of two armed, black-clad protesters standing beside a chipboard spray-painted with the slogan, “ANTIFA 4 BLM”. Trump’s followers agreed: “Democrat mob,” wrote one. “Liberals kneel to anarchy yet again.” The political analyst Michael Scott Doran added that his “friend in Seattle” had told him “businesses are being intimidated by CHAZ/CHOP, which is basically a protection racket” yet “the crimes are being hushed up”. “Some businesses here have already left,” he added. “Trader Joe’s pulled out of Capitol Hill. Others will follow… Socialist paradise will result.”

If you go by these reports alone – which many Americans will – you’d be forgiven for thinking that the small area of Seattle currently run by Black Lives Matter protesters and devoid of police was a terrifying anarchist hellhole. The truth, of course, is so much more mundane. During several particularly vociferous protests, officers within the Seattle Police Department’s East Precinct building decided not to stick around and potentially end up in a standoff with activists. Instead, to the surprise of the people marching the streets and demanding structural change, they shredded confidential documents, boarded over the glass entrance hall of the building and left.

Thanks to some creativity by a talented artist, the sign on the historical building now reads: “Seattle People’s Department” and the railings support signs proclaim “Defund SPD” and “No Justice, No Peace”. The former police building sits in the middle of Capitol Hill, which has been known for the past couple of weeks as firstly CHAZ (the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone) and then, after some ideological discussions between members, CHOP (the Capital Hill Organised Protest.)

In one way, it’s an unprecedented situation. In many others, it’s tradition. As Margo Vansynghel and David Kroman have pointed out, Seattle has a long history of occupational protests; activists taking over buildings and small areas is how the city ended up with its cultural centre in Discovery Park and its Northwest African American Museum in the Central Area. Even in recent American history, such takeovers in the name of civil rights are hardly shocking. Occupy Wall Street, which began in the financial district of New York City in 2011 and included a permanent encampment in Zuccotti Park, still had members turning up (and subsequently being arrested) as late as September 2015.

How, then, is the small six-block area of CHOP different? Despite no longer identifying as an “autonomous zone” – perhaps because they received threats from right-wing groups of “invasion” in the name of the US and the hysteria of Republicans who claimed that “secession” within the States was now being supported by progressive types – CHOP has set up roadblocks to prevent traffic from entering and has made a deal with police that they will not enter except in “life-threatening” cases. “There are people smoking weed in circles ... and just having normal conversations, and then 20 feet away, you have this large group of people standing around somebody with a megaphone talking about Marxism,” one member of the group told Vox.

What about those masked gunmen and the businesses demanding protection money? Business owners from the area have claimed that the rackets are not real, and the sudden influx of people after months of coronavirus lockdown has been a welcome financial reprieve. Trader Joe’s, which supposedly “pulled out” of the area, says it closed temporarily during the protests and will open again after a “remodel” next week. The Seattle Times claims that Fox News photoshopped pictures of gunmen to make it seem like CHOP was home to nefarious figures who have little in common with the real participants. The Independent’s correspondent in Seattle, Andrew Buncombe, visited CHOP himself and described “activists with bullhorns”, “artists painting designs on the streets” and stalls of people giving out free vegan curry. Needless to say, he was not struck through with terror the moment he wandered past the barriers and started a conversation with the activists.

One CHOP protester, who I’ll call Harry, tells me that he’d been surprised by the “weird” accusations of extortion when he’d heard them. “The only place I’ve ever heard this come from is people being like, ‘So, I read on [a news site] that we’re extorting people? Does anyone know about that?’ No. No one knows. It seems to be a weird rumour without even one event to kick it off,” he says.

There are people smoking weed in circles ... and just having normal conversations, and then 20 feet away, you have this large group of people standing around somebody with a megaphone talking about Marxism

How about the gunmen some right-wing outlets insist are patrolling the streets? “I have seen one person open carry. He has a pistol in a holster. I think he belonged to the John Brown Gun Club? But he explained to me some interesting stuff about gun safety. I’m not a gun advocate but I could understand where he was coming from when he spoke. Still makes me feel mildly uncomfortable but I didn’t feel in danger from him – it’s just that I don’t like firearms.” The John Brown Gun Club is a left-wing, working-class group which also sometimes calls itself Redneck Revolt. Its members describe themselves as “anti-capitalist, anti-racist and anti-fascist”.

Harry adds that CHOP generally feels safe, although it has its moments – one physical fight between protesters who disagreed vehemently about something; a few homeless people with substance abuse or mental health issues who are just passing through. “A lot of the ‘scary people’ I’ve seen photographed or videoed are just local transient residents struggling with [those issues],” he says.

“Usually it’s just someone being a bit loud or unpredictable or making people worry, so [volunteers with mental health training] will just talk to them and try and get them a safer place to sit or be. If they’re distressed, engaging will make it worse, the volunteers will just stand a few paces away and redirect and reassure concerned onlookers.”

Despite the sarcasm of conservatives’ “summer of love” claims, those who are currently staying in CHOP describe it as having a gentle, festival-like vibe: pizza deliveries from sympathetic Seattle residents in cars, an art co-op which even has an area for kids with parents, boxes of granola bars from shops and bodegas, even a “decolonisation conversation cafe” at 11th and Pine which features “lots of sectionals and couches”. A schedule for the cafe ran on the day of writing as follows, according to Harry:

“2pm – How has the last month transformed you and your views on racism?

4pm – How can we decolonise Seattle right now?

6pm – People’s assembly in Cal Anderson Street

8pm – What’s next?”

Rules included remaining compassionate, centring conversations on race, and consulting people in the surrounding area if you want to smoke. Elsewhere, another set of rules entitled “DEAR NON-BLACK PHOTOGRAPHERS” listed basic bulletpoints about respecting people’s privacy alongside questions such as: “Why are you photographing? For personal gain, or to help the movement?” and, “If your work lacked diversity prior to documenting these protests (or highlighting black pain), what’s your plan going forward to diversify your work?” I contacted the artist who made the graphics for the posters, who turned out to be a teenage girl living hundreds of miles away on the east coast. She’d been contacted by a protester in Seattle who liked her work, she tells me, and was happy to contribute artwork to CHOP because she believed in its mission and had been told by friends and family at protests that they’d been photographed without their consent after being teargassed or hit with pepper balls.

The thing that really marks out CHOP as a unique protest is its complete lack of police presence. Since officers walked away from the East Precinct in early June, the zone has been self-governing, necessitating those written rules and the meetings which are held in impromptu outdoor sitting rooms and small tents around the streets. Whatever Trump or Fox News’ views on the matter, there is no evidence any serious crimes have been committed. Like the Black Lives Matter protests themselves, there are inevitably some agitators drawn to the place, but people within CHOP tell me they were always quickly surrounded and either calmed down or escorted away by seasoned protesters who are well aware of the PR damage one testy moment might do to BLM as a movement. That’s another reason for the photography rules, Harry tells me: “I and other volunteers can tell often tell when a cameraman [from a media outlet] is being disingenuous because they stand around not filming until they find a mentally ill resident, and then they get uncomfortably close to them.”

Is this a blueprint for the future of American communities? Some people think so. Though calls to “defund the police” have become very popular in the US, even spreading outside the country, there is a huge lack of clarity about what that means. The phrase was first said, it seems, among protesters who were appalled by US police’s habit of acquiring military arsenal from the Department of Defence; some individual forces from wealthy areas with high local taxes have managed to accrue armoured vehicles, tanks and advanced riot gear, leading to a strange situation in which camouflaged trucks have been seen steering down quiet suburban or rural streets over the past few weeks of protest.

The situation stretches back decades, with one of most shocking examples of such military-style weaponry being used on American citizens in 1985, when Philadelphia became “the city that bombed itself”. If you had no idea that the city of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania once dropped an aerial bomb on its own residential streets, don’t worry: most Americans don’t, and even some Philadelphia natives raise their eyebrows when you mention it. It is, however, a particularly relevant story for the age: a black liberation group known as MOVE, which comprised around 250 people, was started in 1972 by a Korean War veteran known as John Africa. Slowly the group accrued members and moved into a street of terraced houses in the middle of the city. Men, women and children lived according to the principles of anti-racism, environmentalism and animal rights.

For reasons which now seem quite transparently racist, then-mayor Frank Rizzo was obsessed with MOVE and its members. Their houses were repeatedly raided, and their members controversially arrested. When they moved to a leafy, middle-class neighbourhood and began broadcasting political messages by bullhorn, residents complained. Police harassed the group again, and they responded by patrolling their properties with sawnoff shotguns and rifles. Much more involved features have been written about MOVE, but the terrible ending to this escalating series of events came via the firing of teargas and water cannons into the homes on the block, and then an aerial bomb dropped from a helicopter which crushed a number of homes and destroyed the rest with fire. Smoke poured across the city. Though some locals claimed they’d been told to evacuate their homes ahead of time, many clearly had not: 61 homes were destroyed altogether, and 11 people died, including five children.

A lot of the ‘scary people’ I’ve seen photographed or videoed are just local transient residents struggling with [mental health, homelessness or substance abuse]

Though the Philadelphia MOVE bombing is probably the most dramatic example of a police force using its budget to purchase unnecessary military weaponry for use against its own citizens, it did not feel unbelievable when protesters across the country were gassed and shot at with rubber bullets throughout May this year. Your everyday American cop might not seem so different to his international counterparts at first glance, but the fact that so many police precincts across the country have access to a stockpile of arsenal you’d usually only see in a warzone marks them out as very different.

“Defund the police” began as a call to bring the US back into line with other countries. It is a mainstream demand these days, with Instagram full of memes showing the $115bn police budget being redistributed to prop up better housing, a nationalised healthcare system and a separate mental health responder force. On 19 June – which marks the US holiday known as Juneteenth, the anniversary of the official end of slavery via the public reading of the Emancipation Proclamation – even the ice cream company Ben and Jerry’s shared an image of a large ice cream tub marked “Police Budget” being redistributed with a “Defund the Police” scoop into smaller bowls labelled “Affordable housing”, “Job training”, “Education”, “Mental health counselling” and “Substance abuse treatment”.

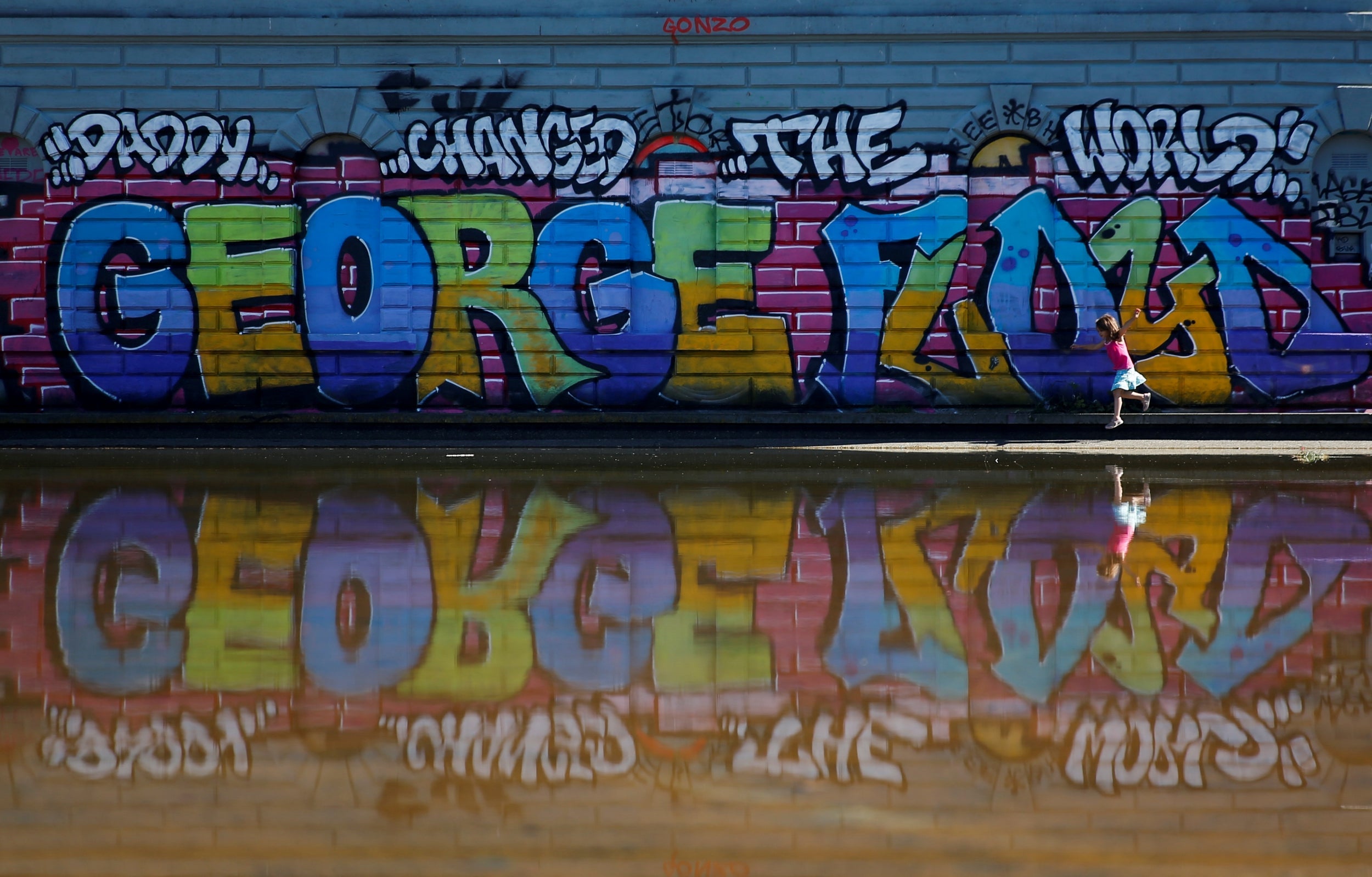

Calls to “defund the police” are popular with many progressive-minded individuals, whereas calls to “abolish the police” are more radical. The city of Minneapolis in Minnesota, where George Floyd died after Derek Chauvin kneeled on his neck for almost nine minutes, has promised somewhat of a halfway house: at the beginning of the month, Mayor Jacob Frey promised to “disband” the police force, to much confusion. It’s still somewhat unclear how that promise will translate into concrete action, though the commitment seems sincere. A few years ago, the Minneapolis police force attempted to “change” by instituting a wellness package for officers and community sessions – and that softly-softly approach doesn’t seem to have worked. Rebuilding from the ground up seems like a good idea.

The US’s $115bn policing budget is extremely high: Americans spend twice as much per person on policing compared to the UK. A quick and easy way to fix some of its more dramatic problems would be to make sure police forces don’t have access to excess funds. Ben and Jerry and their compatriots are correct in that crime and arrests would surely go down if some of that money was redistributed into education, alternative arrangements for drug users and those with mental health problems, rape crisis centres, and a healthcare system that doesn’t leave people desperate and destitute. A redistribution of funds rather than a straightforward defunding is likely to be the most useful and successful strategy. And abolishing the police altogether is an idea which perhaps has legs if it means rebuilding a better system, but is unlikely to work if you consider what usually takes the place of a police vacuum in small American towns: local militias who run things their own way, which very likely turns out not to be in the style of a progressive utopia.

CHOP is proof that communities in America can get by with very little policing, especially in a charged environment. They certainly can get by with less policing than they’re used to, which is – and should be recognised as – an abnormally high amount of involvement for a developed country. Somewhat understandably, moderate Democrats such as Nancy Pelosi have done everything they can to distance themselves from these discussions of late, just as they did when calls to “abolish ICE” gained traction in 2019; they fear that Trump and other hardline “law and order” Republicans will seize on their hesitancy and paint a picture of American anarchy, presumably egged on by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ilhan Omar, the young, liberal boogeywomen of the right.

Pelosi has instead spent her time concocting a package of political efforts for police reform, including the banning of police chokeholds which the speaker has referred to as the equivalent of “lynching”. Controversially, she has also invited police unions to be “part of the conversation” of change, despite the fact that police unions are well-known for protecting their members when they are accused of murder or assault (in Albany, New York, every member of a local police force walked out recently after their colleague was put on administrative leave for allegedly assaulting a Black Lives Matter protester).

One very obvious problem with US policing is the lack of oversight: local police forces are given the power to run themselves with almost complete impunity, making decisions according to their members and their state politicians but few others. Unlike the UK, there is no independent police commission and no federal structure in place for challenging officers or holding them to account when a particularly shocking or egregious act occurs on their watch.

We cannot realistically expect that change will happen fast under Trump’s presidency, especially with Republicans in control of the Senate, but change is happening. Minneapolis is rethinking its policing structure; CHOP is quietly carrying on its protest in Seattle. And while the Capitol Hill Organised Protest is unlikely to last forever, it is testament to the fact that the weeks of demonstrations following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor were more than simply an outpouring of anger and grief.

Out of those marches came a community, and out of the community has come an idea. That idea, multiplied by streets and blocks and small towns and boroughs and large cities across the US, has taken hold. It has a good chance of sticking around for a long time. And if Joe Biden could just win the election in November, we might see a very different America because of it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments