The tragic legacy of Sadako Sasaki and her thousand paper cranes

At two years old, she survived Hiroshima. Ten years later, she died from leukaemia caused by radiation. Today, she’s still a symbol of international peace, writes Olivia Campbell

Sadako Sasaki hung up another paper crane, hundreds of which already brightened her sterile hospital room. She had a mission, but little time to finish it. According to an ancient Japanese legend, a wish will be granted by the gods to whoever folds a thousand origami cranes. Sadako had two wishes. The first was that she’d recover from leukaemia, an illness she’d developed 10 years after surviving the bombing of Hiroshima. When asked by her friends why she was folding so many, she replied: “Why do you think? I want to get better faster.”

She also wished for a better life for her family, peace and a world without war. Sadako’s resolve was strong. A paper shortage after the Second World War wouldn’t stop her. Instead, she used sweet wrappers, discarded gift wrap and even paper from medicine bottles. The young girl soon met her goal of a thousand paper cranes and even made 300 more. However, not even her determination and hope could stop the leukaemia that was coursing through her body. At just 12 years old, Sadako lost her battle.

Her tragic story, however, has managed to reverberate through time. Even today schoolchildren in Japan and around the world learn the tale of Sadako Sasaki, who has become a symbol of peace and the face of innocent victims of war. Seventy-five years after the world’s first atomic bomb was dropped over Hiroshima, the disaster still casts a long shadow, not just for those who survived but for the entire world.

Sadako was two years old when B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped the bomb over the city. At 8.15am, the weapon, codenamed Little Boy, was detonated 580 metres above Hiroshima. The resulting blast and firestorm killed between 70,000 and 80,000 people almost instantly – by December 1945, this number rose to an estimated 140,000 deaths as people succumbed to acute effects such as radiation or burns.

Miraculously, despite being only a mile from ground zero, Sadako was only blown from a window and escaped with barely a scratch. Fujiko Sasaki, Sadako’s mother, fled with her children to nearby Misasa Bridge to escape the flames, but soon the black rain began to fall. A poisonous mix of radioactive ash and dust started to fall from the sky, being breathed in by everyone. Hiroshima had been raised to the ground. Two days later, another bomb would be dropped on Nagasaki.

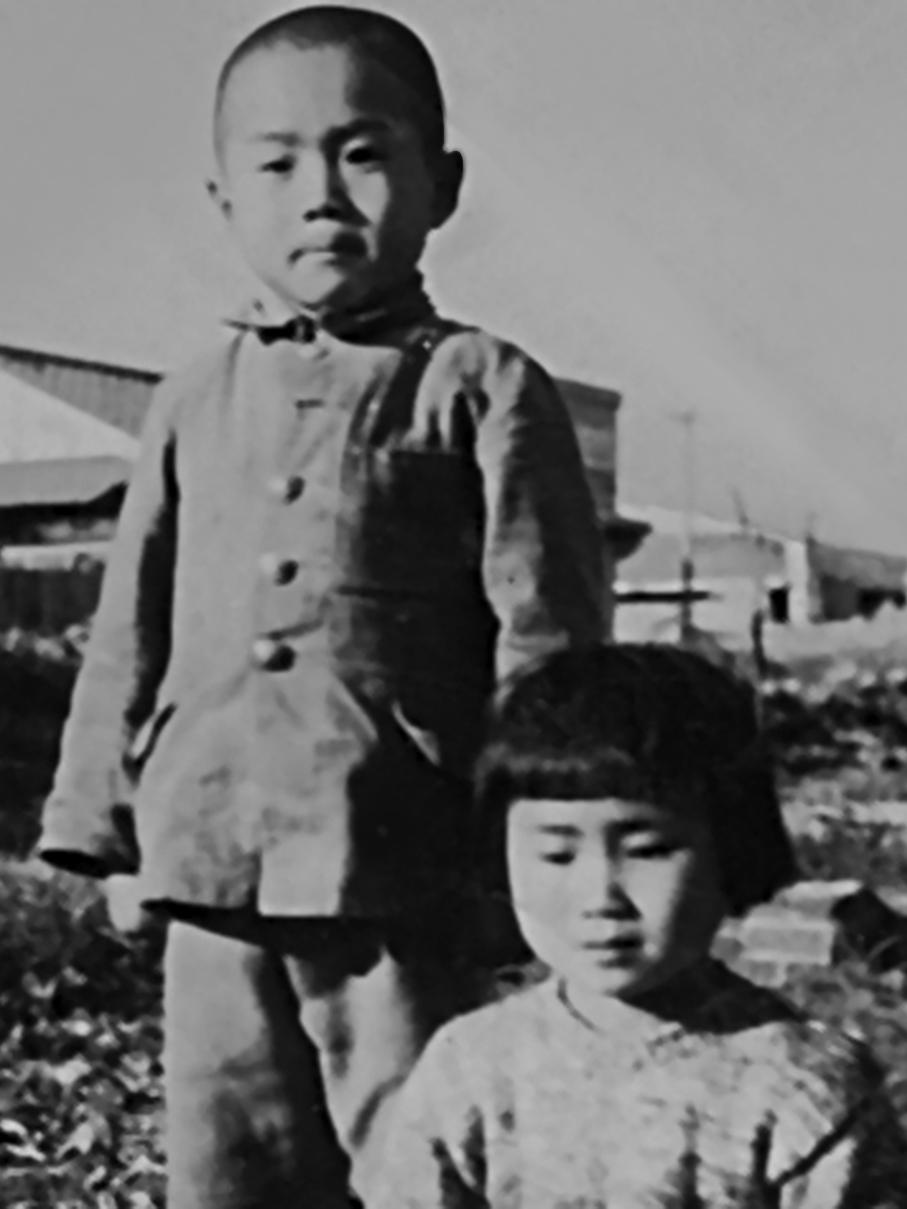

In the decade after that fateful day, it seemed like Sadako and her family were some of the lucky ones. Recovery had been slow and painful, but they’d done it. The Sasaki family opened a barbershop in 1947. Sadako had grown into an energetic young girl and proved to be a gifted athlete; she even had dreams of becoming a PE teacher. It seemed entirely possible that the horrors of the past could be left behind.

However, in late 1954 it became clear that something was wrong. Dizzy spells occurred and lumps began to appear on Sadako’s neck. By January 1955, purple spots could be seen on her legs. Doctors quickly diagnosed her with leukaemia, known among survivors as the “A-bomb disease”, and was given less than a year to live.

Sadako is perhaps the most renowned hibakusha, which translates as “bomb-affected people”. When the bombs were dropped on both cities, at least 100,000 people received injuries of varying degrees, the majority of which were caused by burns that left lasting scars. Radiation poisoning also had a devastating impact.

The initial effects of radiation became visible within the first few hours and subsequent days, but some stayed unseen for years to come. A sharp peak in leukaemia cases during the 1950s, particularly in children, was noted by doctors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A rise was recorded as early as 1949, but the numbers reached their highest within the next decade. Rising rates of tumours, as well as cancers of the stomach, lung, liver and breast as a result of radiation have also been observed.

Sadako’s leukaemia was spreading fast. She was often in pain, but, fearing that her parents would become upset, she hid it. In those final months, her determination to fold cranes kept her afloat; the idea that she might one day leave her hospital room for good and join her friends in junior high school spurred her on. However, by mid-October 1955, her condition changed, and it became clear that her life was near its end. On 25 October, with her family gathered beside her bed, Sadako ate her last meal: tea on rice. “It’s good,” she told them. Seconds later, she drifted off as if she were sleeping and took her last breath.

Those left behind were inspired by her determination and hope. Sadako’s friends from Noboricho Elementary School wanted to do something to honour her life, so they decided to hold a memorial. Their campaign began with the publication of a small collection of letters Sadako had written but it soon snowballed into a nationwide campaign. Newspapers published stories of their plight, while other schools in the two cities as well as across Japan got involved. Many people had lost loved ones to the bombs and saw a part of themselves in what had now grown into a national campaign for Sadako’s memorial.

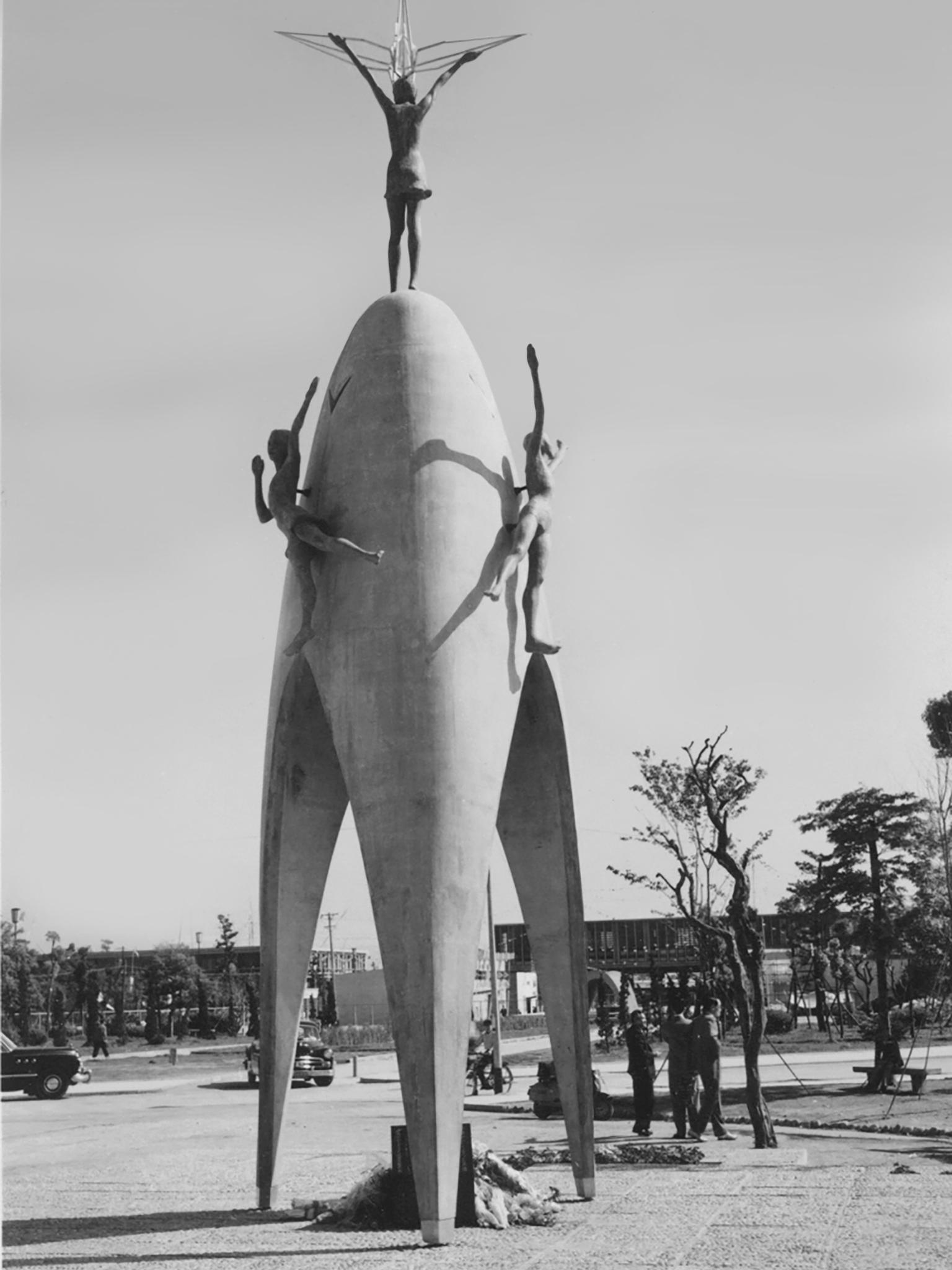

Within a few years, the campaign had raised the funds needed and it was decided that the Children’s Peace Monument would have a permanent home at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. The bronze statue was designed by artists Kazuo Kikuchi and Kiyoshi Ikebe and depicts the figure of a young girl at the top, reaching towards the sky while holding one of her beloved paper cranes. A plaque below reads: “This is our cry. This is our prayer. For building peace in the world.” On 5 May 1958, the memorial was unveiled at a ceremony and the young girl was immortalised.

“Sadako’s story is a powerful one,” says Sue DiCicco, co-author of The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki and the Thousand Cranes and founder of The Peace Crane Project. “She is forever 12, which makes her instantly relatable to children learning about the war for the first time. However, her story is not unique, as many suffered during [the Second World War].

“Masahiro [Sadako’s brother] believes Sadako was sent by God to teach us a lesson about compassion and grace. She has done that for me, and I often think of her when I’m not living up to those ideals. I think she lives in the hearts of many in this way.”

DiCicco set up the Peace Crane Project following the Sandy Hook massacre in 2012, a programme which encourages children to fold a paper crane, write a message of peace on its wings and send it to another child across the world. Since its creation, millions of children in 154 countries have taken part.

Although she hadn’t heard of Sadako when she started the project, DiCicco says educators began sending her letters talking about how they were teaching the young girl’s story to their pupils. Intrigued, she began researching everything about the young girl and spent months looking into her life. Eventually, she managed to meet Masahiro, who recounted memories of his sister, and eventually became co-author of The Complete Story.

Masahiro now dedicates his life to spreading Sadako’s story around the world. In 2000, he began travelling around Japan giving lectures, and in 2009, alongside his family, established the non-profit Sadako Legacy. “Her death gave us a big goal,” Masahiro said. “Small peace is so important [and] with compassion and delicacy it will become big like a ripple effect … It is our responsibility to tell her story to the world. I believe if you don’t create a small peace, you can’t create a bigger peace.”

Sadako’s story is a powerful one. She is forever 12, which makes her instantly relatable to children learning about the war for the first time

Around 20 years after her death, Sadako’s story found a new audience following the publication of Canadian author Eleanor Coerr’s Sadako and The Thousand Paper Cranes in 1977. In Coerr’s fictional retelling of the story, Sadako only managed to fold 644 out of the thousand cranes and it was up to her family to help her finish her dream. The book achieved worldwide fame and remains a widely read novelisation to this day. Other versions have also appeared such as Karl Bruckner’s The Day of the Bomb, which was published in 1961 and sold over 2 million copies. According to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, by the turn of the century, there were at least 23 books based on Sadako in Japan and another 14 worldwide.

There are certainly lessons to be learnt from this tragic tale. This brings up an interesting thought: how do we teach children about the horrors of the atom bomb? It’s a question that is both nuanced and complex – too little and the consequences of one of the most controversial acts of war are lost; too much and we risk traumatising those who are taught. Indeed, the story of Sadako and the narrative of war and peace it fits into is the perfect stepping stone for children to learn.

The first lesson is obvious. War, an entirely man-made concept, causes widespread destruction, taking many innocent non-combatants with it. Sadako’s tale isn’t just tragic because she lost her life; it’s tragic because it represents all the victims of the atom bomb who had their lives cut short in the name of foreign policy. People saw either themselves or individuals they once knew in the tale of the paper cranes.

The true impact of the war is told in the people. Sadako’s story, and the stories of all victims of war, should always be heard so we remember there are many losers in war

After the war, learning about the true nature of the atomic bombs was initially slow. Until the early 1950s, the damage the bombs had caused was largely censored in the Japanese media. Press codes put in place by General Douglas MacArthur ensured that information about things such as radiation poisoning only trickled into public discourse by the mid-Fifties. The end of US occupation in 1952 brought a lifting of official censorship; the hibakusha could now start telling their stories and a generation of children who survived the bombings could begin to understand their past.

There is also a lesson to be learnt about Sadako’s optimism and hope until the very end. “Her story gives us the chance to view the war in a new way,” explains DiCicco. “Her bravery and resolve were as heroic as any soldier, fighting for peace and harmony instead of conflict. Through Sadako, we can appreciate the power of a simple act, and a true heart.

“The true impact of the war is told in the people. Sadako’s story, and the stories of all victims of war, should always be heard so we remember there are many losers in war, no matter who wins.”

The story of the thousand paper cranes is a key part of the curriculum in many schools, many of which seek to emphasise the legacy of Sadako and her desire to live that has eclipsed her short life. Even today, thousands of Japanese children make the journey to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial to leave their paper cranes.

Although Sadako was buried with most of her beloved cranes, some have found their way around the world. In a poignant gesture towards forgiveness and reconciliation, one has been donated to the Harry S Truman Library and Museum, while another was given to be displayed in the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbour, Hawaii. The bomb, authorised by then-president Truman, and the surprise attack on Pearl Harbour has left deep scars in both Japan and the US collective memory. It was a hope of Masahiro’s that the gesture would be a catalyst for change.

A paper crane can also be found in New York at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum. The delicate red crane, smaller than a fingernail, can be found near Ground Zero. Others can be found in the Peace Library at the Austrian Study Centre for Peace and, of course, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial.

On the 75th anniversary of Hiroshima bombings, the number of survivors who experienced that fateful event in 1945 is slowly fading away. Their hundreds of thousands of stories risk being lost to the passing of time. Had Sadako lived, she would have been 77 and her story would have been completely different. Would she have achieved her dreams of being a PE teacher? Would she be standing up beside other survivors, imploring the world to never forget?

It is woven into Japanese tradition that cranes are mythical beings who live for a thousand years – a symbol of both peace and longevity. Thanks to the enduring nature of Sadako Sasaki and her thousand (plus) paper cranes, it is entirely possible that her story might live on for another thousand years, with each generation after the next learning what exactly we lose when humanity goes to war.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments