Why are there two codes of rugby and why do they hate each other?

As rugby league turns 125, Mick O’Hare looks back on its fractious relationship with sibling rugby union and wonders if the two can finally live side by side

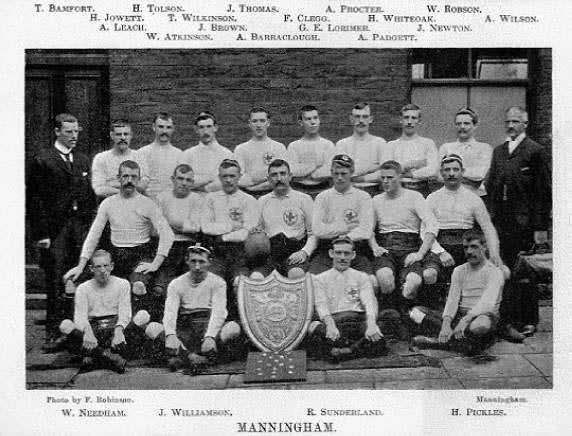

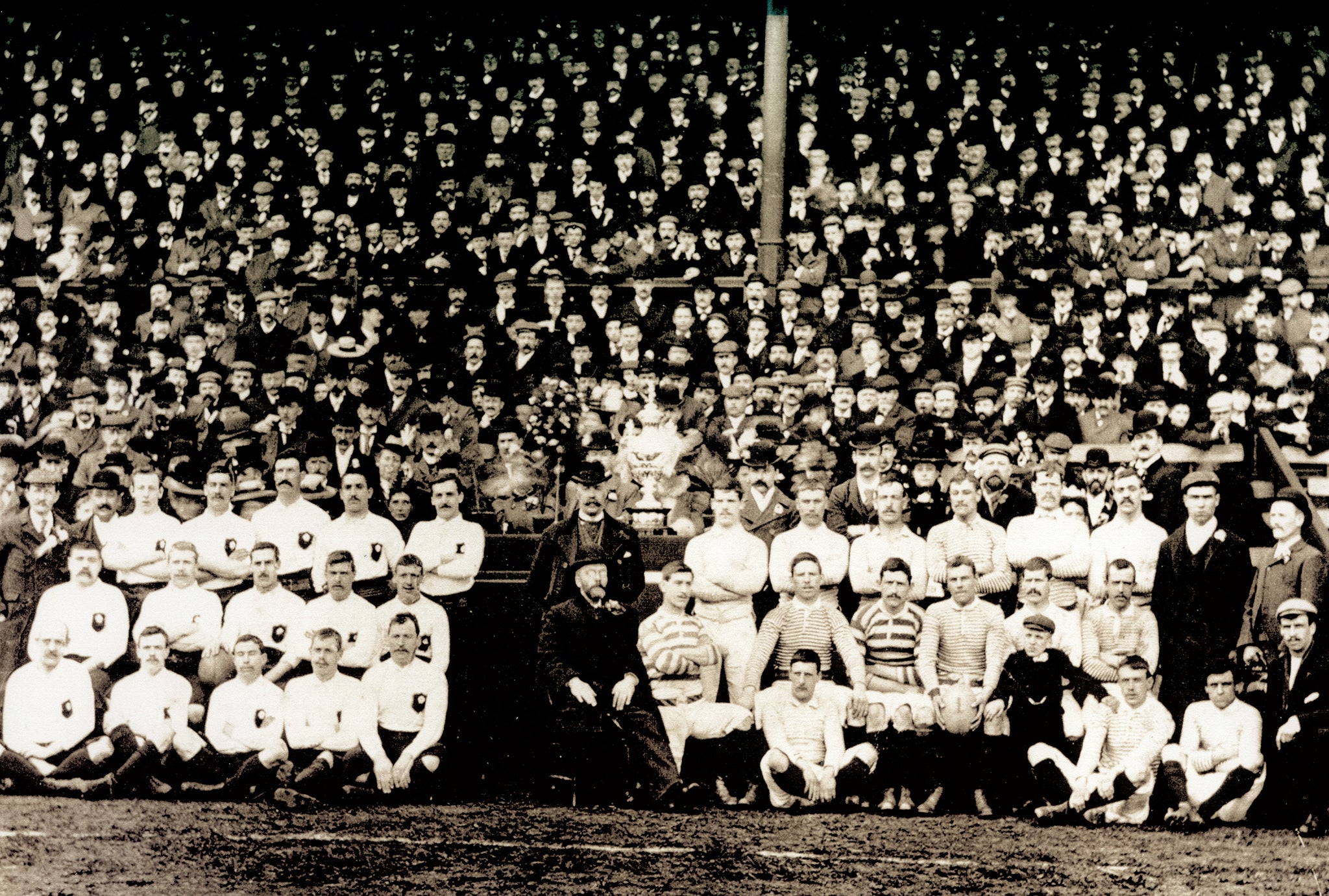

One hundred and twenty-five years ago in a smoke-filled bar-room in northern England, delegates representing 22 rugby clubs committed what broadcaster Michael Parkinson once described as “an act of social insurrection to compare with the resistance shown at Tolpuddle 61 years earlier”. They created what we know today as the game of rugby league.

In June, Rugby League Cares, the sport’s charitable arm, announced the Grade II-listed, Corinthian-inspired George Hotel in Huddersfield would house rugby league’s new museum. Closed since 2013, the building had recently been purchased by Kirklees council and was where the delegates met on 29 August 1895 to announce the formation of the Northern Union, the precursor to rugby league. It is one of the few sports in the world that can pin down its creation to an exact date.

But why did they do it? What happened in 1895 to leave us with two sports called rugby – league and union – which, for a century at least, pretty much hated each other? Indeed, how many people, even today, know there are two kinds of rugby? And if they do, do they wonder why? What was the reason for a rebellion since described as being as significant to the history of the British class system as the Peasants’ Revolt or the Luddite uprisings?

It’s a story of socio-economic defiance and of the political and economic changes emerging in Britain towards the end of the Victorian era. It laid bare the increasing differences of class and aspiration between the kind of people who were now playing the sports first codified in Victorian public schools and once considered the preserve of upper and middle-class gentlemen.

“For many rugby traditionalists, the fact that teams of miners, dockers and factory hands could defeat teams of privately educated players threatened the class structure of Britain,” says Tony Collins, professor of history at De Montfort University and author of the recently published Rugby League: A People’s History.So significant was the breakaway of northern clubs from the London-based Rugby Football Union (

RFU), that it became known as the schism – a word more usually reserved for religious discord – because the political differences that led to it transcended mere opinion. They went to the heart of how Victorian England was structured. “The 1890s were a period of rising working-class self-confidence, as seen in the growth of trade unions and the Independent Labour Party, and of growing middle-class fears of what that assertiveness meant for them. That was the core of what was happening in rugby,” Collins explains.

The catalyst for the rift was “broken time”. Sport in that era was increasingly divided between those who thought it reasonable to pay players for their ability, and those – especially in society’s higher echelons – who believed it should remain an amateur pursuit. Professionalism had no place in an ethos tied to the notion of the “Muscular Christian” – playing by the rules, with honouring God through sporting endeavour being of far more importance than victory.

But sport was now being played by a far larger section of society and by people who didn’t share the creed of Muscular Christianity and saw no reason why, if they were good enough, they shouldn’t be paid for it. Football, eventually, embraced professionalism, certainly as its working-class popularity grew, while cricket got around the “problem” by separating its players. Teams had two changing rooms, one for Gentlemen (the amateurs) and one for Players (the professionals).

The RFU ramped up pursuit of those deemed to have accepted money, enforcing bans on players and clubs. Amateurism was a moral crusade and rugby was being contaminated by the lower orders

Yet some sports pretty much insisted on “pure” amateurism at the highest level well into the late 20th century; athletics, rowing and swimming among them. But at the forefront of the fight to stop filthy lucre “infecting” their game was the RFU. The president of the RFU in the late 1880s, Arthur Budd, said that if “the working man cannot afford to play the game, then he should do without”.

But working men were now playing Budd’s game and with matches taking place on Saturdays, then a working day, players from the factories, shipyards and mines of northern England were having to miss shifts to play. Northern rugby clubs, always keen to encourage paying spectators through their gates to watch the best players, started to demand that those who missed work be compensated for their “broken time”.

The RFU refused, ramping up pursuit of those deemed to have accepted money, enforcing bans on players and clubs. Amateurism was a moral crusade and rugby was being “contaminated by the lower orders”. The battle was long and hard with many twists and turns but, in August 1895, things came to a head. Enough clubs, mainly in Lancashire and Yorkshire, wanted to take control of their own affairs.

And while the schism has been regarded as a victory for the working man, freeing him from a life of being in hock to the owners of mills and mines and giving him the opportunity to be paid for his sporting ability, that was not necessarily the whole story. In many ways Michael Parkinson was wrong when he described the schism as a wholly working-class rebellion against an intransigent establishment whose snobbishness was matched only by its obstinance.

Perhaps it wasn’t so much class rebellion as self-interest. Part of the reason rugby was popular in northern towns was that entrepreneurs rich on coal, wool and cotton were sending their offspring to rugby-playing private schools in the south. They returned and set up clubs. When the public saw the game, its popularity surged and owners were able to charge spectators to watch. So although broken time was the catalyst, those same owners – many of whom were equivocal on the notion of amateurism – realised that if the teams in their locale, especially wealthy clubs in the big industrial cities of Leeds, Hull or Bradford, split from the RFU then they would have nobody to play – and no gate money.

They weren’t necessarily the class rebels they have been made out to be – many were wealthy capitalists, others such as the Reverend Frank Marshall were staunch believers in Muscular Christianity. Marshall, known as the “witchfinder general rooting out incipient professionalism” was so wedded to the cause he even reported his own club Huddersfield to the RFU in 1893 for breaching amateur regulations. But Huddersfield, like the other 21 clubs at the George Hotel, were pragmatic. For a sport so closely affiliated with the political left, capitalist imperatives finally forced the decision, coupled with the determination of the uncompromising RFU, to drive them out. This was as much the source of unity among the 22 clubs as “doing the right thing” by their players.

Phil McGowan is the curator of the World Rugby Museum at Twickenham which, although ostensibly showcasing rugby union history, has a room devoted to the schism. He says: “The attitudes of the rebel club owners were so at odds with the RFU’s values that in the end it was simply more convenient for the two to separate. It reflected wider changes in society and was just one of the more obvious fault lines. Two totally different cultures.” In many ways the Northern Union was forced into existence by the stubbornness of the RFU rather than being the rebellion it is often portrayed as.

And from that point on it was pretty much open warfare for the best part of a century. The mutual hatred “tended to be pathological”, said the author and novelist Geoffrey Moorhouse, who penned a compilation of essays on rugby league entitled At the George as well as its official history.

The establishment in this country hated the very existence of rugby league. They detested everything it stood for. We were kept below stairs

Lifetimes bans from rugby union were the order of the day. Arthur Budd wrote that “it will be the duty of the Rugby Union to see that the division of classes dates from the dawn of professionalism”. George Rowland Hill, secretary of the RFU in 1895 and the first person knighted for services to rugby union (nobody has been knighted for their rugby league connections) made sure the RFU’s institutional influence ran deep. It seems incredible today but rugby league – an entire sport – was banned in the armed forces and in universities in Britain and the former British empire.

In France until recently rugby league was outlawed in schools (and could not use the word “rugby” in its name – it had to use the lowly moniker Jeu à Treize, or “game of 13 [players]”). Most egregiously it was banned outright by the collaborationist Vichy government in Nazi-occupied France during the Second World War and by the apartheid regime in South Africa, where it was deemed a “degenerate” game.

“The establishment in this country from 1895 hated the very existence of rugby league. They detested everything it stands for,” says David Hinchliffe, former MP for Wakefield, and author of Rugby’s Class War. Hinchliffe was instrumental in working through parliament to overturn the bans imposed on rugby league in the armed forces and elsewhere. “We were kept below stairs,” says Maurice Lindsay, former chief executive of the Rugby Football League.

The excuse, for the best part of a century was, of course, “professionalism”, even though thousands played rugby league as amateurs, spending their own money to turn out for small clubs or pub teams. It didn’t matter, they had “professionalised themselves” simply by playing rugby league – and although professional footballers, cricketers and jockeys were all welcome to play rugby union, if you had played rugby league you were banned for life.

“The union authorities pursued instances of professionalism with zeal,” says McGowan, “right up until union itself went professional in 1995”. Some bans were farcical. In the 1930s a rugby union player from Bristol was spotted watching (not playing in) a rugby league match at Leeds. He received a lifetime ban. And at the 1959 general election the candidates for the seat of Wakefield were invited to kick off a rugby league match at Wakefield Trinity: they walked on to the field, kicked the ball and walked off again. The following week the unfortunate Tory candidate, Michael Jopling, later a government chief whip, received a letter from the RFU banning him from union for life. Sometimes the insults exchanged verged on the childish. “A simple game played by simple people,” said Australian rugby union winger David Campese of rugby league. “Union is a complex game played by wankers,” retorted Laurie Daley the former Australian rugby league captain.

1895

The first game of rugby league is played in Yorkshire

Apocryphal stories abound too: league people like to think the story of William Webb Ellis, a pupil at Rugby School, picking up the ball and running with it to create the sport of “rugby” is a myth invented to cement union’s ownership of the game. “That may be so,” says McGowan, “although we currently have no proof either way. We do know the first written laws of any football code were those produced at Rugby School in 1845.” For certain the plaque at Rugby School identifying it as the sport’s birthplace was erected post-schism, again presumably to assert ownership.

And there’s been a long-held belief that The Battle of the Roses, a painting by William Barnes Wollen, depicting a match between Yorkshire and Lancashire in 1893, which hangs at Rugby Union headquarters at Twickenham, had the faces of players who switched to rugby league painted over in retribution. But McGowan, a meticulous historian of both codes, thinks it unlikely.

“One Yorkshire player is missing,” he says. “And it’s possible he was removed to allow the addition of RFU secretary Rowland Hill. But the other faces are identifiable. Yet nearly all went over to rugby league, so why weren’t they all painted out?” asks McGowan. At the time, however, the story probably suited both sides of the rugby divide: that of union’s institutionalised power to eradicate its enemy and that of league’s innate sense of injustice.

For its part rugby league ploughed its own furrow after 1895. It quickly realised the rules needed changing. To attract paying audiences the game had to speed up with fewer stoppages. The differences introduced to ensure it was distinct from union were all pretty much in place within the first 15 years.

And its administrators also realised that to survive, the game had to expand. So although to this day rugby league is considered synonymous with “the north”, that underplays its worldwide growth, especially since 1995 when newly professionalised rugby union could no longer ban players for trying league. While league has long been popular in Australia, New Zealand, France and, fascinatingly, Papua New Guinea where it’s the national sport, competitions exist in countries as diverse as the United States, Jamaica, Russia, Lebanon and Serbia. But even on its own doorstep it’s a little acknowledged fact there are more amateur rugby league teams in London than there are in, say, Wigan or Hull, areas often considered the sport’s heartlands.

But one region where rugby league failed to put down deep roots, despite it providing hundreds of players for professional rugby league teams, is Wales. It’s paradoxical too, because the strength of Welsh rugby was in working-class communities, much like northern England, where antipathy towards the ruling body in London was equally strong. Had Welsh clubs defected to rugby league in 1895 today’s rugby landscape might be wholly different. But the Welsh Rugby Union (WRU) played a canny game. It deliberately turned a blind eye to professionalism in their clubs. Amid accusations of “shamateurism” they knew that by looking the other way players might not defect to rugby league, but even if they did the north of England’s professional teams merely acted as a safety valve helping to keep union dominant in Wales.

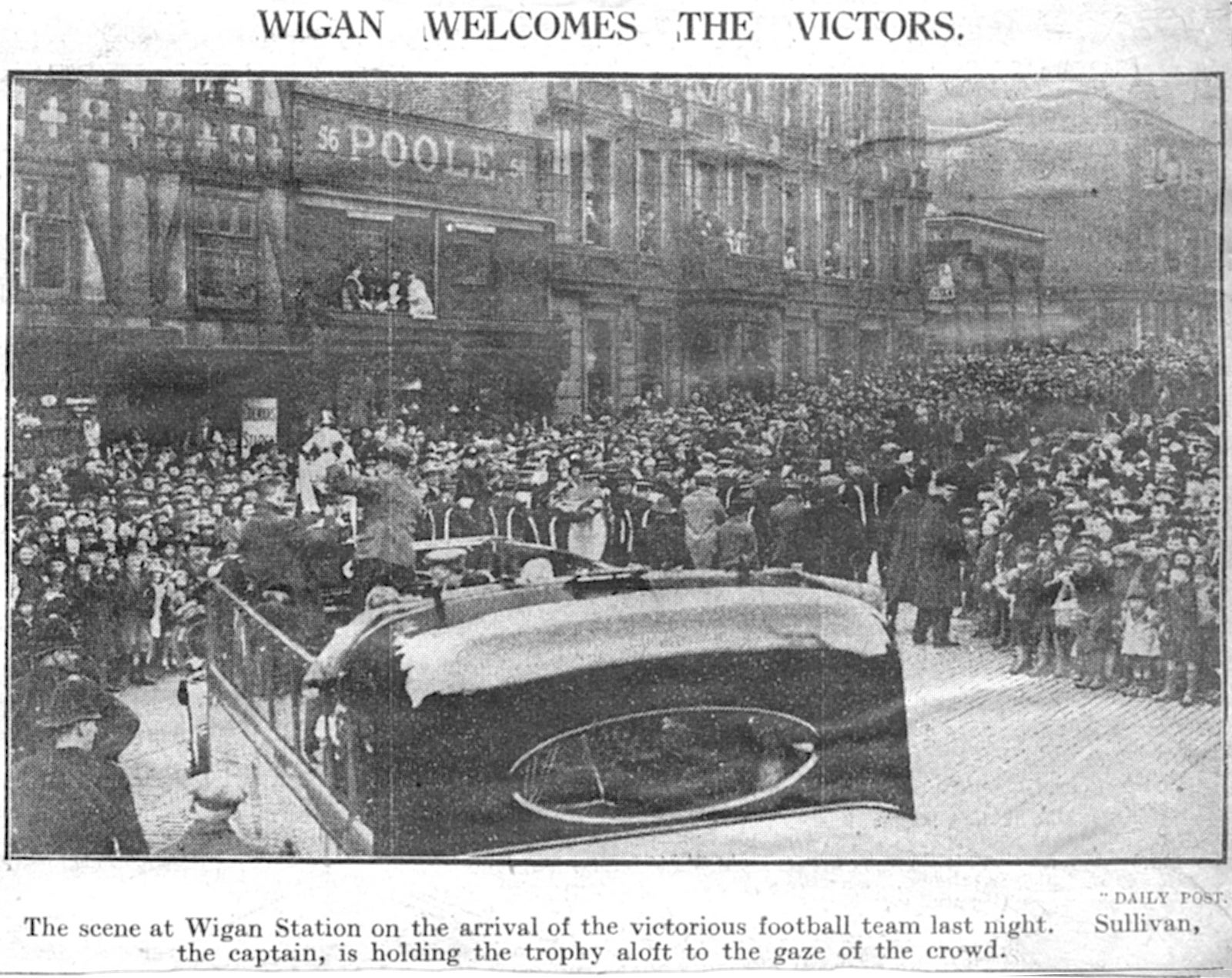

Probably a thousand Welsh union players “went north” in the century after the formation of rugby league, many of them famous names such as Jim Sullivan and Jonathan Davies. It was an incalculable loss to the Welsh national team but a price worth paying as far as the WRU was concerned.

Similarly, rugby league acted as a refuge for black players, many also Welsh. It was an unwritten rule that no black player would be selected at union for Wales or indeed many other nations, so the likes of Billy Boston, Colin Dixon and a host of other fine black Welsh players – one of whom was Danny Wilson, father of footballer Ryan Giggs – switched to rugby league. It allowed Welsh-born Clive Sullivan to become the first black captain of a British sports team when he captained Great Britain at rugby league against France in 1970, a full eight years before any black player would play football for England.

Of course, racism existed in rugby league at that time, just as it did (and does) in all sections of society. But club owners realised crowds wanted to watch winning teams which meant signing the most skilful players irrespective of colour. It was as much expediency as it was emancipation. Nonetheless rugby league was way ahead of other sports in Britain – not just rugby union.

The accumulated politics of the last 125 years accounts for the reason rugby league people wince when they are lumped in with the generic term “rugby”, as though there is only one sport. You could hear the collective cries of thousands of league supporters earlier this year inserting the word “union” when there was consternation over the racist connotations in what was termed “England's rugby anthem”; the African-American spiritual song Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.

It would never be heard at a rugby league match. Equally rugby league people find it infuriating when talk turns to the “Rugby World Cup”, official shorthand for the union version. League’s preceded it by 33 years. In this century the Daily Mail was still describing rugby league as “not everyone’s cup of tea” as though every other sport was, and has led to Hinchliffe describing the experience of being a rugby league supporter as having “a deeply held, almost innate, sense of grievance”.

And, although there may have been genuine causes for this grievance (a chip-on-the shoulder mentality, alongside the belief it owns the moral high ground, has arguably served rugby league well down the decades), it’s also fair to say that its supporters can see a slight where none exists.

Take the case of Eddie Waring, the BBC’s long-serving rugby league commentator. His knockabout, catchphrase-ridden style infuriated many. The notion persisted that the establishment BBC was keeping rugby league in its place, refusing to give it the reverence the corporation reserved for rugby union. It was almost certainly complete tosh. Waring’s biographer Tony Hannan says “back then most national newspapers had Manchester offices so it wasn’t always the ‘London-based’ media to blame. As Eddie said ‘It’s not my fault if the cameras honed in on Blackpool tower or a coal train rattling by at Castleford’.”

Equally it’s absurd for rugby league people to blame the average union supporter for the ills of Vichy and apartheid, although perhaps it has led to league being quicker off the mark in being “woke” in its dealings with, say, minorities and women. Next year’s Rugby League World Cup sees the women’s, disabilities’ and men’s competitions taking equal billing. “We’ve always been inclusive,” says tournament chief executive Jon Dutton. “Rugby league has continually disrupted the norm.”

But we are now 125 years on from the George Hotel and rugby union itself went professional in 1995, almost a century to the day after league. How do the codes view each other today? Every so often the odd spat from a more distant past flares up – most recently in 2015 when Sol Mokdad, a Lebanese national who attempted to organise a rugby league tournament in the United Arab Emirates was jailed and deported when that country’s rugby union authorities reported him for setting up an “illegal rugby competition”.

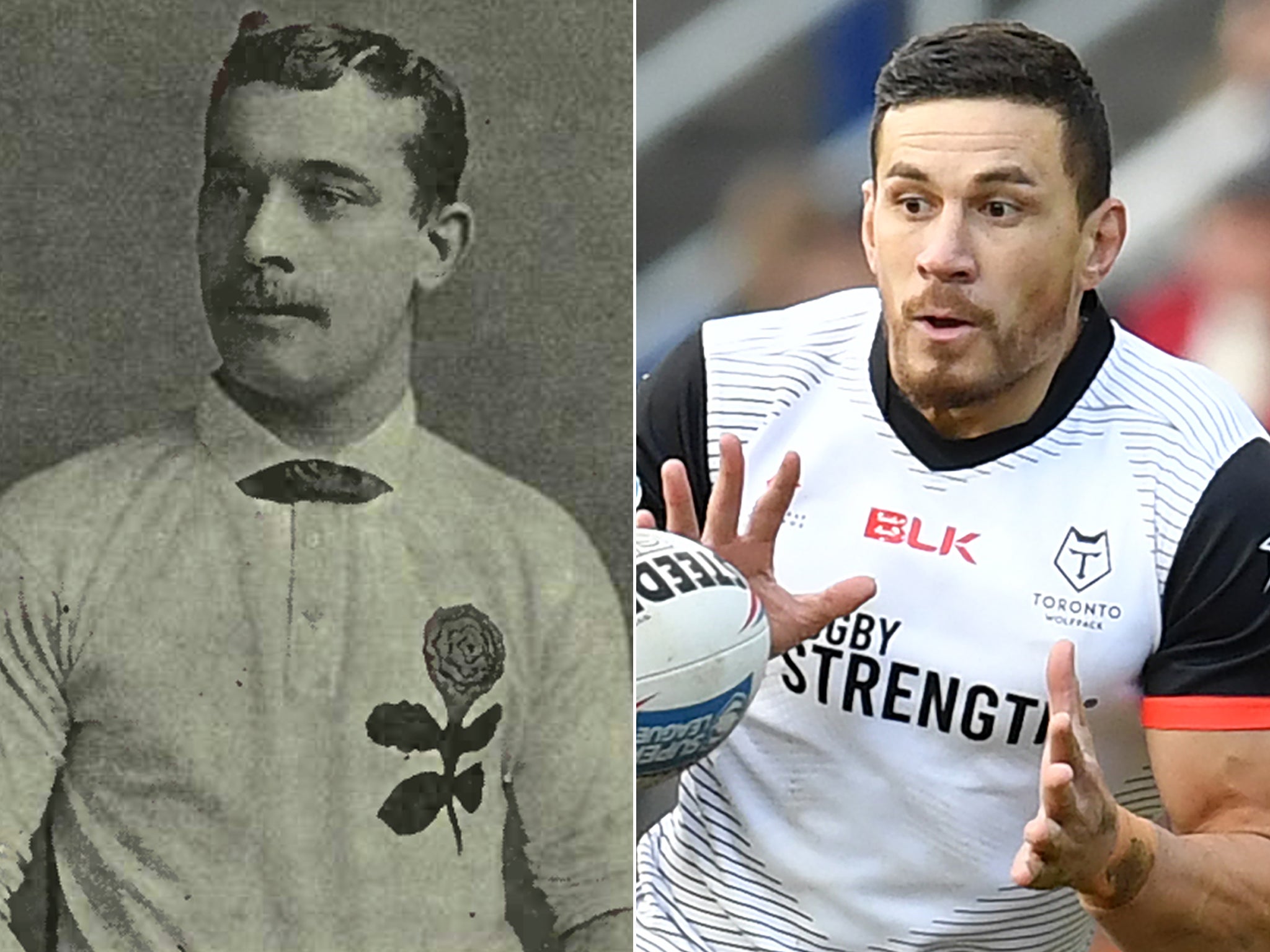

But these days there is far less animosity, certainly between the governing bodies and the players, if not always the spectators. Détente has replaced contempt – in fact in many cases admiration has broken out. “Undeniably union and league have a shared history and many of the greatest performers have benefited from playing both,” says McGowan.

"From Dickie Lockwood and Jack Toothill in the 1890s to Jason Robinson and Sonny Bill Williams in the modern era.” John Drake, former editor of Rugby League World, agrees: “At grassroots level things have improved enormously with players swapping freely between codes and genuine co-operation in some places, even between professional clubs such as union’s Newcastle Falcons and league’s Newcastle Thunder, which was once inconceivable,” he says.

As it professionalised, rugby union players became fitter and the rules adapted to make it more entertaining (much like the process league went through in its early years). Certainly it would be far harder for Wigan’s rugby league team to win union’s Middlesex Sevens tournament as easily as they did in 1996, beating famous names Harlequins, Leicester and Wasps at their own game.

When even Shaun Edwards, a former England captain and the most decorated player in rugby league history – a man who had the words “rugby league running through him like a stick of Blackpool rock” according to one biography – can make a name for himself as a coach of the Welsh union team it’s clear the rugby world has come full circle . Such a crossing of the rubicon would have seemed impossible when Edwards signed professionally for Wigan on his 17th birthday in 1983. When a Rugby League World Cup match was played at Twickenham in 2000, rugby’s Berlin Wall was finally deemed demolished.

Today, in the nations where both codes have a major presence, the relationship is almost wholly positive. Dutton points out his team was invited to the last union world cup in Japan to study best practice “and we will reciprocate at our tournament next year,” he adds. “Despite the acrimony of the past, now more than ever our values are aligned: teamwork, respect, enjoyment, discipline and sportsmanship,” says McGowan. He points out that in the Twickenham changing rooms above each player’s bench is a list of notable predecessors who have played rugby union for England.

Some of these – Dickie Lockwood among them, a Yorkshireman and former England captain once banned and excised from rugby union history for his links with professionalism – crossed the divide to play rugby league and earned their lifetime bans. “This would have been unthinkable even 20 years ago,” says McGowan.

So will “rugby” ever be a single sport again? The RFU remains coy on the possibility, preferring not to comment but Drake doubts it: “That seems to be a vision largely promoted by people who have little affinity with or understanding of either code, their distinct identities or cultural backgrounds. A single code could never exist – the differences between them are too great on the field and off it too. The communities that have sustained Rugby League would simply never countenance it. If attempted over their heads, I’m certain they’d just start another breakaway.”

Later this year – Covid-permitting – the Australian rugby league Kangaroos will play the rugby union New Zealand All-Blacks in a 14-a-side hybrid rugby game. Doubtless cold war warriors on both sides will deem it a circus act, something to excite only TV companies and marketing departments. On the other hand, even before the pandemic, sports clubs of all types were struggling to stay afloat – joining forces to create a single game might have great appeal, sporting and financially.

Ray French, the former BBC rugby league commentator who played both codes internationally, is more equivocal than Drake about a hybrid rugby code. He has said “the strength of rugby league is along the M62 corridor in the north and union along the M4 corridor in the south. Economics and finance one day will bring them together. It could be a game to rival football in this country.” A lot of water would have to pass under a lot of bridges, however.

One thing rugby league has proved to itself and the world around it is that it is resilient. Another joke in rugby league circles is how many times it has survived beyond the “just five years” so many members of the fourth estate’s sporting scribes have constantly predicted it has left before fading into oblivion. The first appeared in 1895 and they’ve been materialising regularly since. Hinchliffe has documented them all: “They’re mainly written by people who’ve hardly ever watched a game of rugby league, having been brought up in the union tradition,” he says. “The prediction fundamentally fails to understand why rugby league exists. It was never just professional rugby union…”

Those delegates at the George Hotel in 1895 were probably aware of the strife that would follow. Whether they expected it to be raging 125 years later, however, seems unlikely. And as for whether it was a rebellion to match that of Tolpuddle or the Luddites or just pragmatism at work, well maybe it was a bit of both.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments