Will the 2020s be just as roaring?

As a new decade begins, Ed Power is reminded of how quickly a century slips by. In 1920, the global economy was recovering, technological wonders were revolutionising people’s lives and the far right was on the march. Sounds familiar...

The world seems to spin faster than it ever has before. A wave of dazzling technological breakthroughs have transformed the lives of ordinary people. Old certainties are swept away. Excess is everywhere: you can practically inhale it. Has there been a better time to be young and footloose?

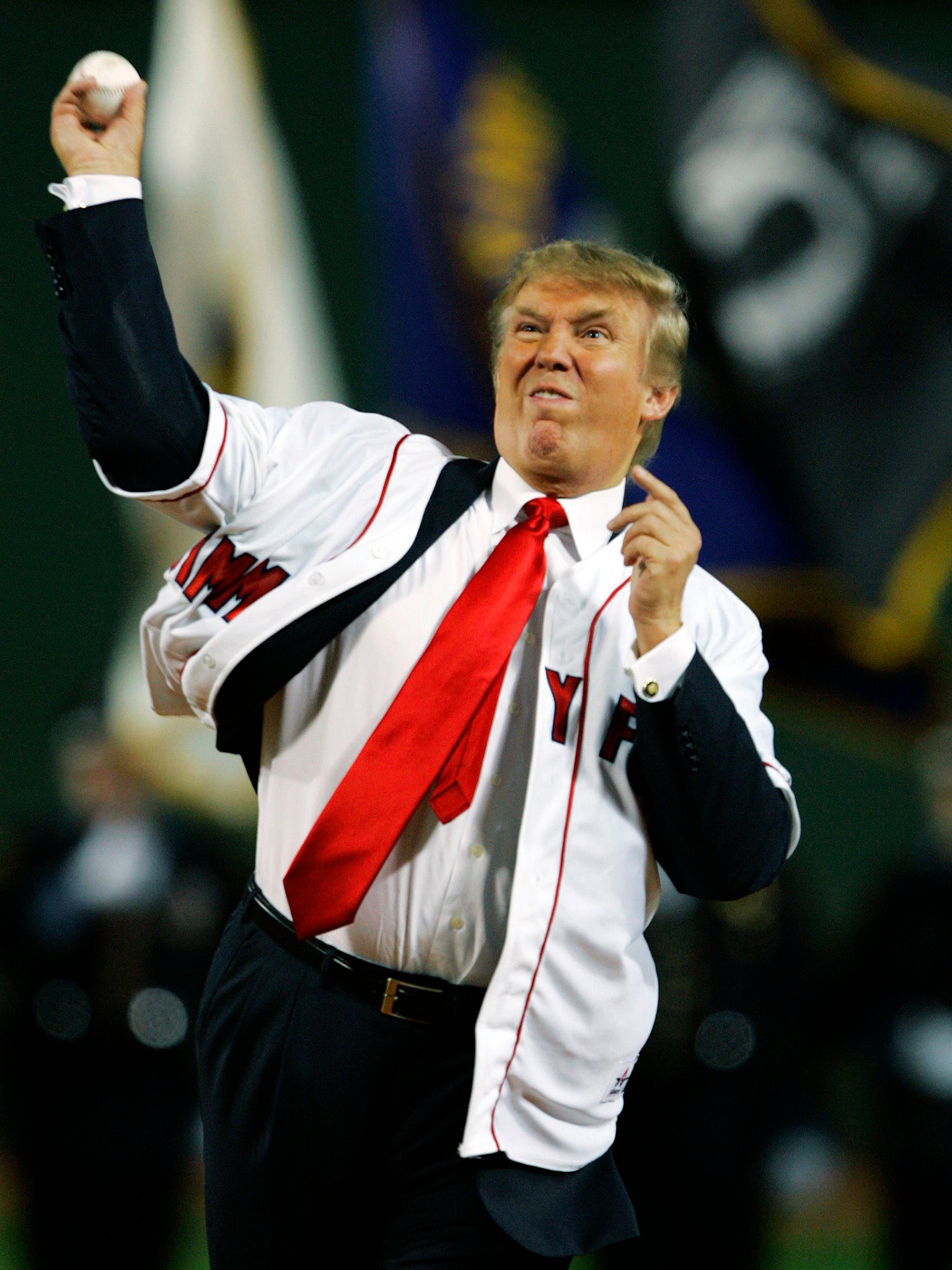

Shadows linger on the horizon, it is true. Intolerance is on the rise; emigrants have become an easy target for politicians chasing the chimera of populism. The White House is occupied by a “densely ignorant” Republican with a chequered personal life, specialising in meandering and contradictory public statements. Across the Atlantic, Britain is faced with the fracturing of the Union. Meanwhile, huge wealth disparities endure. For many, getting through the week is as much a challenge as in decades past.

But oh such distractions. The public thrills to a new class of celebrity whom they feel they know as well as they do their best friend. These are heady days for music, literature and film, where blockbuster entertainments are the order of the day. People are worked to the marrow but party as if time is running out. And time really is running out, though when this becomes finally clear it will be too late to do anything about it.

Squint slightly and we could be describing the world as it faces a new decade: the 2020s. And yes, how strange to think that a “new” 1920s is coming around. To our grandchildren the “1920s” will refer not to the era of flappers, Al Capone and Charles Lindbergh flying across the Atlantic. It will mean the epoch in which Britain left the EU, Donald Trump fought to retain the White House and… well, whatever comes after that.

The dawn of this new Twenties is a reminder, also, of how quickly a century clips by and of the briefness of human existence (anyone with adult memories of the other, “real” Twenties is now long gone). Did the citizens of 100 years ago feel as discombobulated by the turning of the wheel as we do today? Were they gazing over their shoulder towards the 1820s – those glory years of Lord Liverpool as prime minister, the incorporation of Florida into the United States and formal adoption by Australia of its name – and think, crikey, those were the days?

And might they also have panned the timelines, looking for the twinkle of historical parallels? To do so is a very human compulsion. We cannot help but discern similarities between the world poised to enter the 2020s and the state of civilisation 100 years ago. In both instances, the global economy is recovering after a period of instability: one caused by war, the other by the mother of recessions. Technological wonders are never-ceasing. Our relationship with the concept of celebrity is undergoing rapid change. And the far right is on the march.

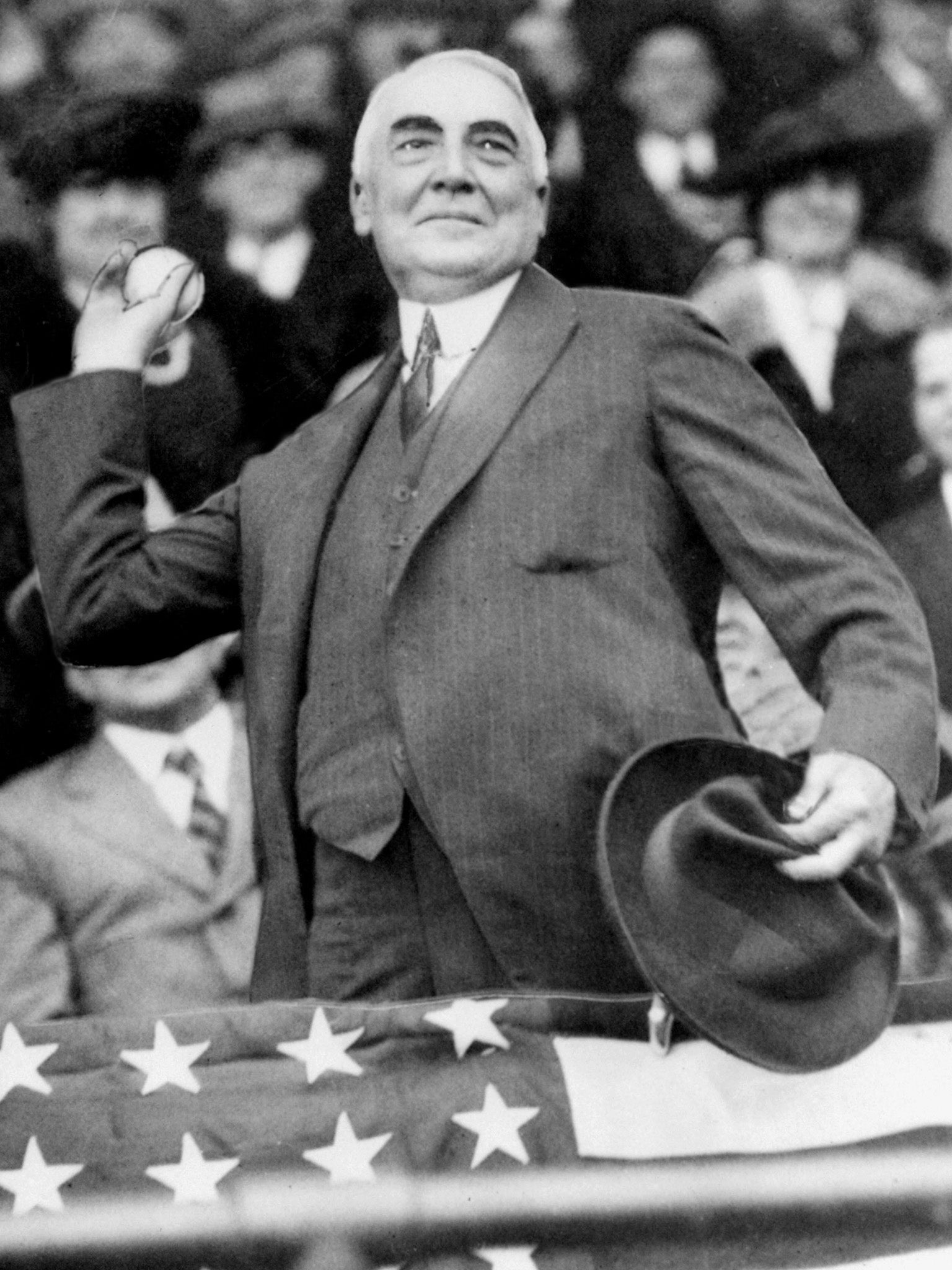

If anything, the politics of the early 1920s were significantly calmer than today. In the United States, President Warren Harding was a figure of ridicule, tolerated by the Republican establishment but only because he was perceived as having the common touch. They regarded him as a safe pair of hands: unimaginative yet on their side.

Still, Harding was no less colourful than Trump, in his way. There were mistresses, too many to keep track of (on the eve of his inauguration he had to be prevented from sneaking out for an after-hours assignation). Alas, his expertise in the boudoir was not matched in the debating chamber.

The president, wrote journalist William Allen White, was “densely ignorant… at best he was a poor dub… uttering resounding platitudes and saying nothing because he knew nothing”. Harding was hugely popular, though – an archetypal man of the people. His “genius”, historian John Hicks observed, “lay not so much in his ability to conceal his thought as in the absence of any serious thought to reveal”.

There wasn’t much very Trumpian about Harding’s politics. Nativism was nonetheless on the rise. In 1924, 12 months after Harding suffered a fatal heart attack at age 57 and was succeed by 49-year-old vice president Calvin Coolidge, congress passed the Immigration Act. Backed by overwhelming bipartisan support, the legislation imposed drastic quotas on immigration to the US. There were especially severe limitations on nationalities and races regarded as “un-American”, among them Jews, Italians and Poles. Today’s immigration crackdown in the US carries echoes of these sentiments.

Harding had been too busy chasing mistresses to whip up anti-migrant sentiment. Coolidge, by contrast, enthusiastically stoked intolerance. In 1921 he had written an article for Good Housekeeping titled, “Whose Country Is This?” Not that of Jews, Italians, Mexicans, Poles or Irish, Coolidge baldly stated. He warned of “the alien who turns toward America with the avowed intention of opposing government, with the set desire to teach destruction of government”.

“There are racial considerations too grave to be brushed aside for any sentimental reasons,” he wrote. “Biological laws tell us that certain people will not mix or blend. The Nordics propagate themselves successfully. With other races, the outcome shows deterioration on both sides. Quality of mind and body suggest that observance of ethnic law is as great a necessity to a nation as immigration law.”

Did the citizens of 100 years ago feel as discombobulated by the turning of the wheel as we do today? Were they gazing over their shoulder towards the 1820s – those glory years of Lord Liverpool as prime minister, the incorporation of Florida into the United States and formal adoption by Australia of its name – and think, crikey, those were the days?

Steve Bannon – Donald Trump’s far-right spirit animal – might have nodded his approval. Coolidge’s hyperbole came amid the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, which set crosses ablaze across the American South. Al Smith, a Democrat and the first Catholic to run for president, recalled crossing the state border from Kansas to Oklahoma on the campaign trail in 1928 and seeing huge crucifixes burning across the hills.

Britain faced all too familiar challenges too. Scottish independence may well become reality in the next 10 years. A century ago, Ireland was about to depart the Union, having essentially voted for independence in the 1919 general election. Not that London saw it that way as it unleashed a paramilitary rag-tag upon the country, who burnt cottages and shot into the crowd at a football match.

It is unimaginable that Brexit and its constitutional fallout in Scotland would unleash a similar blood bath. But the threat to the Union is surely no less severe than was the case ahead of the signing of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, which lead to the partition of Ireland.

Bonar Law, Conservative prime minister from 1922 to 1923, was no Boris Johnson. Still, he wasn’t above playing the gallery. In 1912, as Ulster Unionists armed themselves with weapons procured illegally from Germany he had been happy to rabble-rouse, saying: “I can imagine no length of resistance to which Ulster can go in which I should not be prepared to support them.”

Still, as prime minister the course he steered was steadier than such rhetoric suggested. He had come to power in a general election after his party had deposed his predecessor David Lloyd George against a backdrop of rising industrial strife. The Tories comfortably won the 1921 election. For the first time, however, their chief rival was not the the Liberal Party but Labour. Class was about to define British election politics. A century on, with the Northern “red wall” crumpling, has that dynamic now exhausted itself?

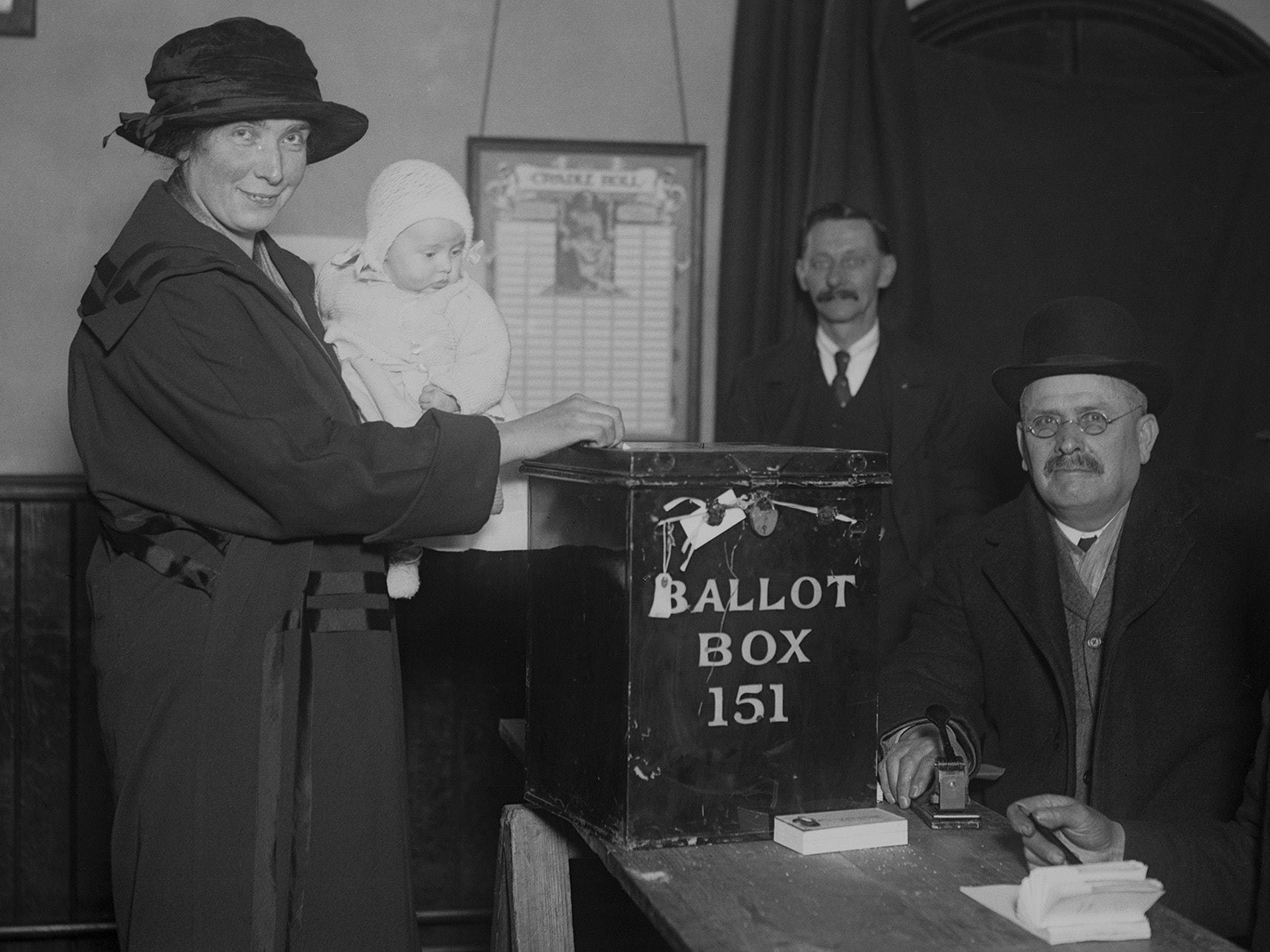

Suffrage was still a novelty in the 1920s. Women were granted the vote in the US on 18 August 1920 (Harding was the first president elected by both genders). In the UK suffrage was introduced on a qualified basis in 1918 (the vote restricted to women over the age of 30), with the limit lowered to 21 in 1928.

Today, the trend appears to be in the opposite direction. Voter suppression is, for instance, regarded as a clear and present threat to democracy in the United States. By the end of 2018, more than half of American states had passed laws criticised for making it more difficulty for minorities to vote.

There are plenty of things that were once commonplace that are now illegal such as smoking inside. When we look at the damage eating meat is doing to the planet it is not preposterous to think that one day it will become illegal

“In 2020, we’re poised to see more voter intimidation,” wrote Carol Anderson, author of One Person: No Vote: How Voter Suppression is Destroying Our Democracy. She warned of industrial scale “criminalising of voter registration drives, disguised poll taxes, attempts to maintain extreme partisan gerrymandered districts, draconian and flawed voter roll purges, squashing access to voting on college campuses widespread purchase of hackable voting machine”.

Fears it is becoming harder, not easier, to vote have also been voiced in the UK. In his October Queen’s Speech Johnson outlined new laws requiring voters to produce photographic ID at the ballot box for parliamentary elections and English local elections. This prompted the Electoral Reform Society to caution that “these plans will leave tens of thousands of legitimate voters voiceless”.

Technology in the 1920s was turning society upside down. Henry Ford had invented the modern production line at his Michigan Model T factory in 1913. By 1920 mass production was becoming standard across industry, rendering much manual labour redundant.

The result was industrial unrest across the world, and terrorist attacks by anarchists in the United States. That many of the saboteurs were Italian deepened American suspicion of foreigners. So did the Russian Revolution and the rise of the Soviet Union. The fear in the 1920s was of Russian communists spreading sedition abroad. We still worry about Russian interference today, though in the guise of fake social media accounts and internet bots rather than as reds under the bed.

The future of the workplace also seems in jeopardy today, as it was in the 1920s. As artificial intelligence becomes an everyday reality, how soon before many “irreplaceable” positions are consigned to the annals? By 2030 perhaps a computer will be writing an article such as this and journalists will have joined the ranks of the horse-and-cart driver and the ice delivery man. Workers may become as rare a sight in the offices of tomorrow as on Ford’s stripped-down production lines.

But if there was uncertainty 100 years ago there was also joy. Cinema and the mass media had introduced the public to a new kind of celebrity. Early movie stars such as Lillian Gish and Mary Pickford were the Zoellas of their day. They traded on attainability and relatability. And they understood that to retain their status as “influencers” they had to keep their public onside. Pickford, already married, was for instance reluctant to go public with her relationship with Douglas Fairbanks for fear of alienating the masses.

And of course it was the age of Prohibition, which lasted in the United States from 1920 until 1933. One hundred years on, it is unthinkable that alcohol would be banned in the west. If anything, the trend, in terms of mood-altering substances, is in the opposite direction as more and more countries and American states legalise marijuana.

Yet we are still cracking down on popular, everyday pursuits. Smoking has become ever more prohibitive due to punitive taxes and now governments are moving against carbonated drinks and junk food (see the “sugar tax” introduced in the UK in 2018). Vaping is the public health concern of the day, amid fears it will corrupt our youth and lead them down a bad path. And at the Labour conference last September, respected QC Michael Mansfield suggested meat could be outlawed because of its contribution to climate change. This would be a historical turning point on a par with prohibition – the first time a “natural” human activity (we did, after all, evolve to consume our fellow animals) was legislated against.

“There are plenty of things that were once commonplace that are now illegal such as smoking inside,” Mansfield said. “When we look at the damage eating meat is doing to the planet it is not preposterous to think that one day it will become illegal.”

Where does it all end? The 1920s boomed as the global economy recovered from the First World War. In the United States today, 10 years of sustained growth since the 2009 recession has set a new record.

Yet even as the world economy ticks over, intolerance rises. Paranoia about communists and anarchists has been replaced by Islamophobia and the alt-right’s crackpot “replacement theory”. Amid the giddiness and the glamour, a darkness was rushing headlong towards those living the best days of their lives in the 1920s, culminating in the Great Crash of September and October 1929. Whatever the decade ahead portends, we can only pray it does not lead somewhere similar.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments