We need to talk about rail fares ... and this is a good time to bury bad news

They say you should never waste a crisis, so let’s not waste this one. As Simon Calder anticipates a hike in ticket prices, he says there has never been a better time to restructure the system and encourage more people onto trains

At 2.56pm on 11 September 2001, an aide in the Department for Transport (DfT) sent an email to the then transport secretary, Stephen Byers, saying: “It’s now a very good day to get out anything we want to bury.” Jo Moore wrote the message within an hour of the second aircraft hitting the World Trade Centre in New York.

The notorious “good day to bury bad news” memo led to a series of resignations in the DfT and – we can but hope – reminded ministerial aides of the need to show respect for the British public and the wider world. Nearly two decades on, we are engulfed in another crisis. Many thousands of lives have been lost. And the DfT has been presented with another opportunity to bury bad news: this time about how some rail fares must rise.

The pricing structure for Britain’s trains is an impossible mess of 55 million different fares. Supposed safeguards were “baked in” during privatisation in the 1990s. Despite the online revolution, a quarter-century of government inaction has left us with paper tickets in a smartphone age, loopholes as wide as Waterloo station available for those of us who care to use them, and a sense of injustice among those who are obliged to pay more than £1 per mile for peak-time journeys.

Many passengers pay much less, while tens of millions of taxpayers who never go near a train underwrite the whole expensive muddle. To “even up Britain”, radical change is desperately needed. It will certainly be detrimental to some. But the expression “never let a good crisis go to waste” has never been more appropriate.

As a result of the collapse of passenger numbers, ordered by the government, the privatised train operators have all been given public financial protection. The railways have been effectively re-nationalised. With many people’s working patterns likely to be transformed after the coronavirus crisis, the traditional season ticket looks increasingly obsolete. Commuters, and those of us who simply want to use a train to reach somewhere appealing, need a better deal.

The baked-in absurdity that an off-peak single from London to Carlisle costs £90, but the return journey adds only £1 to the cost, should be abolished – with rail fares for inter-city journeys sold in single legs, just like budget plane tickets. The government has a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reform rail fares, incentivising people to switch from car to train when social-distancing rules are relaxed – and using price to flatten the peaks, especially on morning services to the biggest British cities.

Rather than bring out changes under cover of Covid-19 while everyone’s attention is elsewhere, there should be forthright public, cross-party debate. Starting now.

We need to talk about rail fares. Anyone who needs a “walk-up” ticket from Edinburgh to Lancaster would be a fool to ask for one. Instead, they should request a ticket to Preston. Even though the latter is 25 miles further from the Scottish capital, the fare is lower. And the “Didcot Dodge” is famed throughout the land: the £112 one-way peak fare from Bristol to London shrinks by £44 if you have the good sense to buy two separate tickets and travel on a through-train that pauses at the Oxfordshire “Parkway” station.

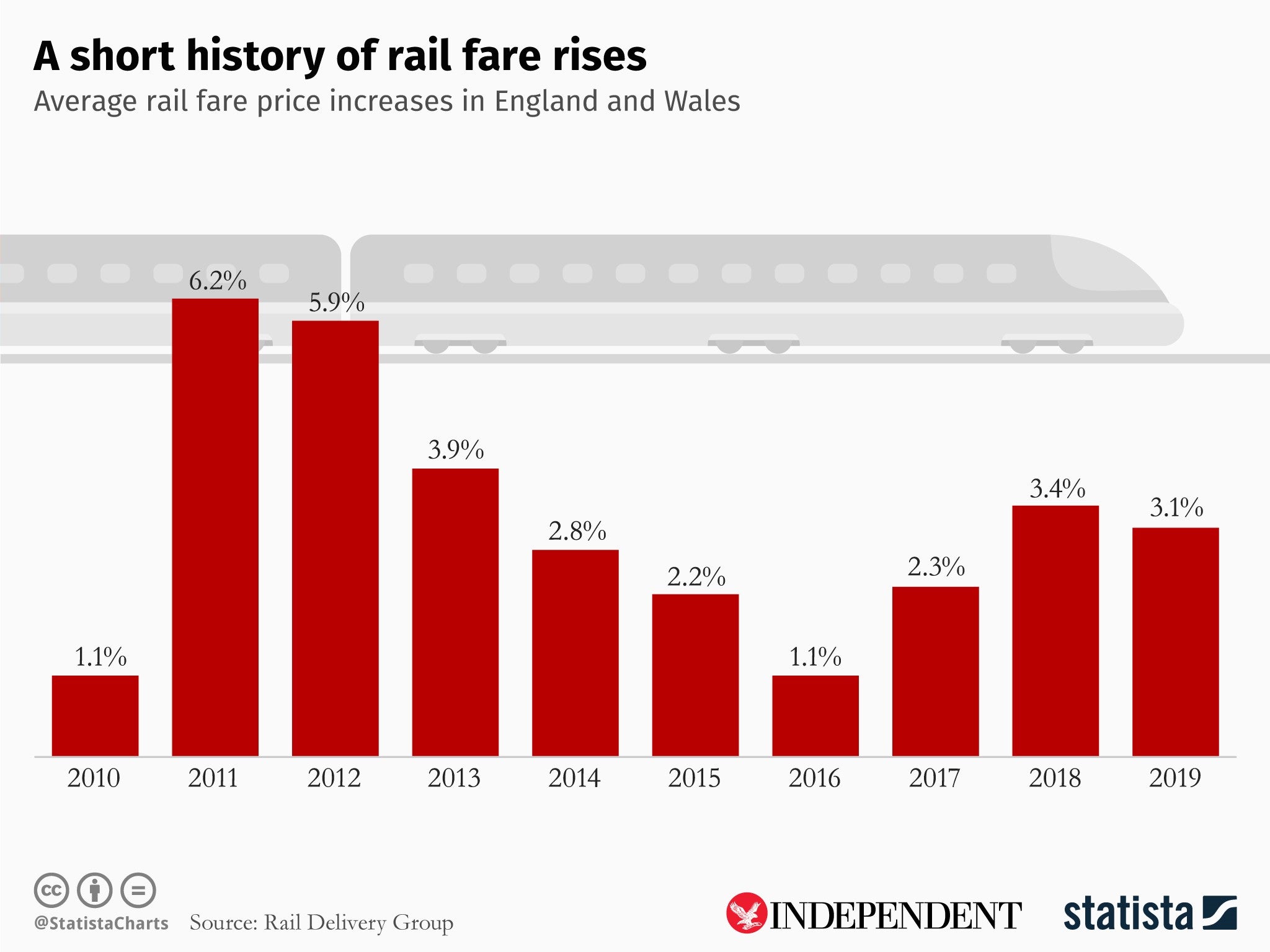

Everyone agrees the current system is nonsense. The price you pay for your ticket is decided by a Byzantine 20th-century array of fare regulations that are as absurd as they are arbitrary. The rules were frozen in time in the mid-1990s in a half-hearted attempt to protect the passenger from privatised train operators. But they were not frozen in price, which is why any UK transport journalist knows that the same basic story can be retold on three annual occasions: mid-August, late November and the first working day of the New Year.

The summer date is when the July retail price index (RPI) is published. This calibrates the amount by which regulated rail fares will rise the following January. It requires only a few taps on a calculator to reveal that the price of a Brighton to London season ticket is set to increase by x hundred pounds.

By November, the train operators have calculated the exact fare rises. When they reveal them, the media, the unions and the Labour Party get another good kicking.

Our proposals would not only open the door to tap-in-tap-out travel with price capping across the country, but could help reduce overcrowding on some of the country’s busiest services

The final appointment in the train-fare trilogy usually takes place on 2 January. The standard ceremony is at King’s Cross station in London when – until this year at least – Jeremy Corbyn and various rail union bosses helpfully turn up to provide re-nationalisation sound bites and demands for an unaffordable return to the days before driver-only operation.

Sir Keir Starmer, Corbyn’s successor, is coincidentally the MP for King’s Cross, St Pancras and all stations to Euston. I hope not to meet him at King’s Cross next year – because by then the whole system should have been overhauled. The DfT already knows that fare revenue in 2020 and for years to come will be well short of the previously reliable £10bn. And with the economy in turmoil, you need not be Mystic Meg to predict that July’s inflation could be anything from sharply up to deeply negative. Not to act ahead of the summer RPI revelation would be irresponsible.

Going back to 2001 at least, everyone has said: “We must sort out the fares system.” But exactly nothing has happened. Because if all else remains equal, some will be worse off. While many fares will fall or remain much the same, some will increase – probably quite sharply.

The same space-time peculiarity that generates the “Didcot dodge” means a passenger heading west from the Parkway station to Swindon pays £26 for a 15-minute hop, while much the same distance going east to Reading is just £10. When they are evened out, the passengers who face higher transport costs will, understandably, make much more noise than the quietly delighted Wiltshire commuters.

That is exactly what has scared transport secretaries from Stephen Byers onwards away from what they know to be the right policy. The strategy that dare not speak its name also involves surcharging “super-peak” passengers – reducing crowding on rush-hour trains by applying premiums for the right to arrive at Manchester Piccadilly, Edinburgh Waverley or London Waterloo between 8am and 9am.

The answer to the question ‘how many passengers can be crammed on to the 7.44am from Woking to Waterloo?’ should not be ‘two more’. It should be ‘as many as are comfortable’

The answer to the question “how many passengers can be crammed on to the 7.44am from Woking to Waterloo?” should not be “two more”. It should be “as many as are comfortable, with others incentivised by lower fares to travel earlier or later”. The standard sound-bite from long-suffering commuters is that the fares are too high and the trains are too crowded.

Perhaps while the trains are largely empty, I can venture that these unfairnesses are mutually exclusive. Were the fares really too high, there should be no trouble getting a seat. Since we rely on Victorian infrastructure that is already at full capacity, the only option is to regulate demand with some judicious, if infuriating, price hikes.

The good news is that it need not be a zero-sum game. Deregulating pricing will allow train operators, whether or not they are owned by the state, to adopt revenue-maximising techniques from the airlines. Filling the billions of empty seats that trundle around Britain each year would bring environmental benefits as well as boosting revenue overall.

“Buying inter-city tickets online needs to be made less like solving a quadratic equation,” insists Mark Smith, the former British Rail manager who founded the Seat61.com website for global train travellers.

He is on a mission to destroy the Didcot Dodge and the many other anomalies. “The current system makes it all too easy to create pricing anomalies where A to B + B to C costs less than A to C. At present the Competition Act legally prevents the manager pricing A to C from talking to the managers in other companies pricing A to B and B to C.”

Fortunately, the rail industry is listening. Robert Nisbet, director of Nations and Regions for the Rail Delivery Group – representing train operators and Network Rail – told me: “The current pandemic is likely to accelerate the changing travel patterns we have already seen over the past decade.

“Now that more people have discovered that they can work remotely and flexibly, our rail fares system needs to be overhauled to catalyse Britain’s economic recovery. Working with government, our proposals would not only open the door to tap-in-tap-out travel with price capping across the country, but could help reduce overcrowding on some of the country’s busiest services.”

The present wretched pause in normal life will be followed by economic hardship for all. To add to the misery by putting up some rail fares to the amount they should have been years ago sounds harsh. But the alternative is to muddle on for decades more. Mark Smith says these dismal circumstances are ideal for bold action: “With far fewer people travelling, if there’s an unexpected revenue hit following a significant change in fares structure it’ll be smaller – with time for the DfT to tweak things before the normal passenger volumes return.”

They say you should never waste a crisis. And in the worst of times, this is the best of times to bury bad fares.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments