Are you racist, sexist, sizeist? Take a test and find out

Sir Keir Starmer urged his party to undergo unconscious bias training but can it help us understand our own prejudices or is it just a corporate sticking plaster to cover up festering wounds? Steve Boggan reports

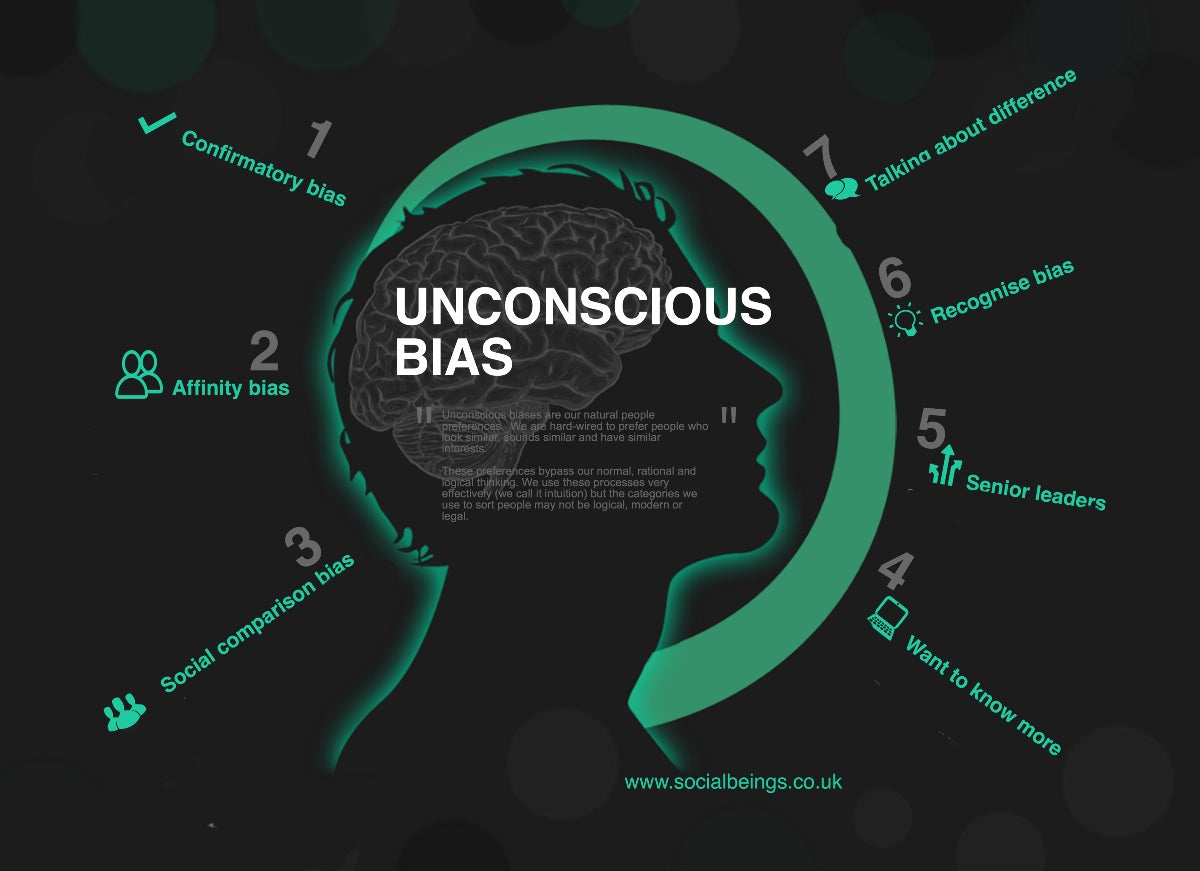

I have just taken a test designed to probe the unconscious prejudices I harbour in the dark recesses of my mind and I’m feeling ashamed as I look at the results. They say I’m a bit racist. And a bit sexist. And somewhat homophobic. And my attitude towards overweight people could be better. My only consolation in putting this out there is that I’m not the only one. You’re probably a bit racist too, and perhaps a little homophobic and generally not as embracing as you could be of people who are different from you. We all are. It’s a natural – but unwelcome – trait in us and it’s called “unconscious bias”.

The principle of unconscious bias was catapulted into the public consciousness this month when Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer said he wanted the Party’s MPs and peers to undergo training to counter it. And, “leading from the top”, he would take the training first. He made his promise during a phone-in to LBC when a caller challenged him on what she saw as less than fulsome support for the Black Lives Matter movement. He had said it represented a “moment”, which might have given the impression that he felt it would pass.

“What I was saying,” he countered, “is that Black Lives Matter needs to be a moment, and I meant a defining moment and a turning point. I didn’t mean a fleeting moment.”

When Sir Keir said he wanted to uncover his hidden prejudices and take them on, two things seemed obvious: first, this was because he couldn’t allow the party to become engulfed in a row about race with antisemitism still in his Inbox. Second, he surely wouldn’t spring something like this on the party without the training already being in place…would he?

After the announcement, I asked the Labour Party if I could go on one of its courses. The reply was perhaps telling: “Your request won’t be possible.” I asked why, but there was no answer. When it later emerged that Labour’s “training” actually involved MPs watching a 20-minute video, the email from party HQ did make sense after all; it probably didn’t have any courses for me to attend. Claudia Webbe, a black Labour MP for Leicester East, described the training as “pitiful”, adding: “Unconscious bias training is neo-liberalism writ large, exonerating whole institutions of [their] unconscious racism.”

So, is unconscious bias training a useful tool in helping us to understand our own prejudices – whether we realise we have them or not – or is it simply a sop, a corporate sticking plaster applied to cover up festering wounds?

The theory of unconscious (Americans often use the word ‘implicit’) bias was first posited by US psychologists Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald in 1995 in their book, Blind Spot: Hidden Biases of Good People. In this, the pair argued that we all carry hidden prejudices and biases as a result of being exposed throughout life to cultural attitudes about race, religion, sexuality, social class, disability, nationality, age and gender.

They used an assessment tool developed by Greenwald called the Implicit Association Test (IAT), in which the subject’s unconscious prejudices are supposedly unveiled when they are asked to react to a series of quick-fire words and images on a computer and then fill in a questionnaire. In an interview with National Public Radio in the US, Banaji described her first encounter with the test, and how it left her feeling.

“I did a very simple experiment with Tony Greenwald in which I was to quickly associate dark-skinned faces – faces of black Americans – with negative words,” she said. “I had to use a computer key whenever I saw a black face or a negative word, like devil or bomb, war, things like that.

“And likewise, there was another key on the keyboard that I had to strike whenever I saw a white face or a good word, a word like love, peace, joy. I was able to do this very easily. But when the test then switched the pairing and I had to use the same computer key to identify a black face with good things and white faces and bad things, my fingers appeared to be frozen on the keyboard.

“I literally could not find the right key. That experience is a humbling one. It is even a humiliating one because you come face to face with the fact that you are not the person you thought you were.”

I felt so embarrassed about that and I still do. My conditioning had told me not to expect a black person to have reached the status of a barrister – unconsciously, I had assumed she must have occupied a job of lower status

I was asked to try several of these tests before meeting Danny Lunan, 54, an associate trainer with Equality and Diversity UK, which conducts unconscious bias and other types of workplace training. “My IATs suggested I might be a bit racist,” I tell him. “And a bit sexist and a tad homophobic and I seem to favour slim people over fat ones.”

Danny, who is black, doesn’t flinch and doesn’t seem to judge me harshly. Then he tells me a story about meeting another black man socially who had told him that his wife worked at a particular law court. “'Really?’ I said to him,” said Danny. “'Is she a clerk?’ The guy just looked at me and then very slowly he said, ‘No. She’s a barrister’.

“I felt so embarrassed about that and I still do. My conditioning had told me not to expect a black person to have reached the status of a barrister – unconsciously, I had assumed she must have occupied a job of lower status. This is classic unconscious bias and it demonstrates how we make assumptions and judgements about people that can have a negative impact on the way we see them.”

At the start of my training, Danny asks me to write down the names of the five people I have worked with who were most important to me professionally. Then we put that to one side. He explains the importance of equality, diversity and inclusion in the workplace. We discuss prejudice and discrimination, its roots, causes and solutions – and how all of this can be undermined if bias exists without the perpetrators, particularly people in positions of power, realising it.

For example, he tells me that in 2012/13, the Higher Education Statistics Agency (Hesa) reported that of the 17,880 professors in British universities only 85 were black and 950 were Asian – the vast majority (15,200) were white. There were only 17 black female professors in the entire system.

“In 2015/16, there were no black academics in the elite staff category, ie managers, directors or senior officials,” he says. “The Hesa said that as a result, non-white academics were less likely to be short-listed, appointed or promoted in comparison with their white counterparts. The agency also found that Bame academics working at top universities were earning 26 per cent less than their white colleagues. There seems to be a failure to accept that this systematic racism even exists. This means that ethnically diverse teaching staff are often viewed by students as being inferior to their white tutors. Universities claim to be ‘colour blind’ when it comes to whom they recruit, but bias appears to have played a part in many of these stories.”

Among the many adherents to the concept of unconscious/implicit bias is Hillary Clinton. Discussing how it affected the behaviour of US police, during one of her presidential debates, she said: “I think implicit bias is a problem for everyone, not just the police. I think, unfortunately, too many of us…jump to conclusions about each other. And, therefore, I think we need all of us to be asking hard questions about why am I feeling this way?”

Neither the IATs nor unconscious bias training are without controversy. The tests have come in for criticism for not reaching acceptable levels of reliability, not least because people who re-take them often get different results. Having taken four, I came to the conclusion that something as simple as a person’s dexterity might affect the outcome. And the way questions were posed was not always without ambiguity.

For example, in a test to establish whether I aligned women with arts and men with sciences, I was asked whether I agreed or disagreed with the statement: “On average, men and women differ in their willingness to spend time away from their families.”

No explanation is given for the final determination that I demonstrated a ‘Moderate association of Male with Science and Female with Liberal Arts’, which I interpret as sexism

The test only allows a one-word reply and mine was “Yes”. Why? Because of my belief – or biased assumption? – that because of wage inequality and the fact that some men simply don’t pull their weight when it comes to family duties, women are often left to pick up the pieces. If responsibilities were split 50/50 in more households, then women could spend more time advancing their careers and not being held back by poor pay and lazy spouses.

Then it occurred to me that the programme’s metrics might have taken that answer to conclude that I would be less likely to employ a woman for that very reason – the demands of home. No explanation is given for the final determination that I demonstrated a “Moderate association of Male with Science and Female with Liberal Arts”, which I interpret as sexism. I will never know, but I suspect it contributed to the result. You can try taking IATs here: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/uk/

Jonny Gifford, senior research adviser at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), the professional body for human resource managers, says that while unconscious bias is a problem of which we should all be aware, the training to counter it isn’t always considered positive. “Even though unconscious bias is a massive problem, it doesn’t necessarily follow that explaining the psychology of this will reduce bias,” he says. “Indeed, unconscious bias training can backfire; that is, it can increase bias. This is because of what psychologists call ‘moral licensing’, [which means] we do something that makes us feel better about ourselves and stop making the effort which is what really makes the difference.

“So, people feel virtuous having done the training and stop making the effort that is needed to keep their prejudices in check. It’s the same reason that people can become less healthy after going on a course of vitamins; they feel virtuous and stop making an effort in things like exercising and eating healthily that are what really make the difference.”

My trainer Danny believes the training, if conducted well, can make a permanent difference in people’s willingness to accept that they have unconscious bias and so push back against it. Mine took three hours and I believe I benefitted from it. At the very least, it will keep my personal antennae twitching.

“Unconscious bias training is not designed to make you reveal your deepest secrets,” he says. “But it can help you understand what informs and drives you, and other people. The training must be delivered in a non-judgemental, non-threatening way. Course content and activities will help attendees explore parts of their personality that they may not have explored before. For this we need buy-in, and a willingness to be self-critical, from the outset. You don’t always get this but when you do, it works.”

Unconscious bias training is not designed to make you reveal your deepest secrets. But it can help you understand what informs and drives you, and other people

I don’t know why the IAT’s algorithm concluded I had a ‘Moderate automatic preference for White people compared to Black people’ – it gives no explanation. I might have been too slow to identify a white person with a bad word or a black person with a good one as the images whizzed before my eyes. So, while the test didn’t overtly describe me as “racist”, the result was enough to arouse in me curiosity and awareness.

I thought my anti-racism credentials had been established when, many years ago, I was part of a team from this newspaper shortlisted for a media award from the Commission for Racial Equality. We had conducted a campaign that resulted in a change in the law that makes it illegal for women from the Asian sub-continent to be forced into marriages against their will. But, of course, might this not be a good example of “moral licensing”? I did my bit and then moved on.

At the end of the training, I was reminded of the five names I had written down who had had a positive professional effect on me. Three were male, two were female. They were all white and all aged within about five years of me. How predictable: I had been shaped largely by people like me.

Jonny Gifford’s moral licensing warnings are crucial to this debate, but if individuals and institutions, companies and political parties make conscious decisions to try harder, and not to pretend a single 20-minute video constitutes a serious effort stamp out bias, then perhaps properly conducted unconscious bias training should be allowed to make its mark. We are all inherently flawed. The sooner we recognise those flaws – and do something about them – the sooner the world will be a better, more equal, place.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments