Shapurji Saklatvala, the Labour firebrand who fought for racial equality in the 1920s

MPs of colour have held seats in the Commons since 1767, writes Kim Sengupta. Those battling for equality today owe much to the pioneers who challenged the establishment – often at great cost to themselves

At the start of this century the House of Commons had 12 MPs from ethnic minority backgrounds. This had increased to 41 after the 2015 election, and currently stands at 65 across the main parties in Westminster. As the protests last summer, against prevailing racism in society as well as the legacy of slavery and imperialism, showed, injustice and discrimination, or the anger it sparks, is still very much with us. And as the campaign for equality looks to the future, there is increased interest in those who had fought for equality in the past through the democratic mandate – often at great cost to themselves.

MPs from non-white minority backgrounds were present in the Commons long before communities from the Empire moved here in numbers, some of them achieving positions denied to them in the countries of their birth by the colonial rulers.

Some were descendants of slaves. The first MP from a minority background, it is believed, was James Townshend, whose grandmother was of African and Dutch descent. He was elected member for West Looe, in Cornwall, in 1767. Richard Beckford, who won the seat of Bridport, Dorset, in 1780, was the son of a plantation owner and an enslaved Jamaican woman.

John Stewart, elected MP for Lymington in 1832, was the son of a plantation owner of mixed race. Henry Galgacus Yorke, who won York in 1841, was the son of a West Indian of African and British descent. David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre, elected MP for Sudbury in 1842, was of mixed European and British descent. Ernest Soares, whose father was Indian and mother English, became the Liberal MP for Barnstaple in 1900.

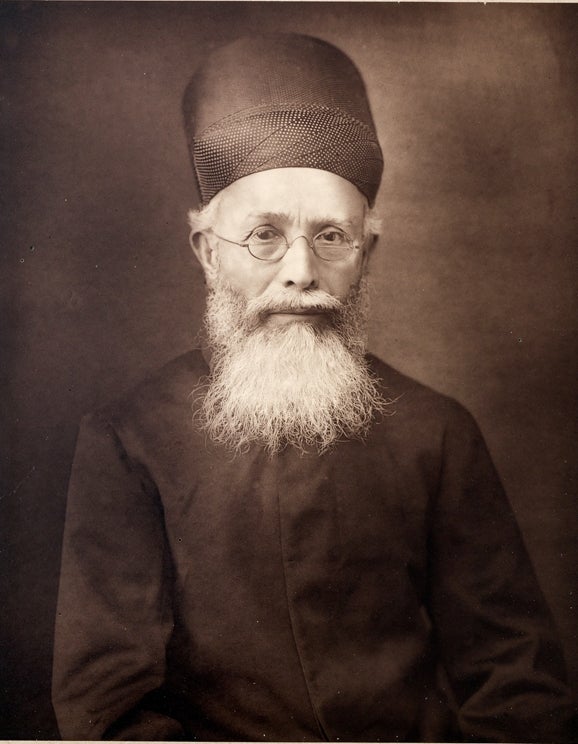

When Dadabhai Naoroji, a distinguished academic of Indian background, stood in the 1886 election, the Conservative prime minister Lord Salisbury declared: “However great the progress of mankind has been, and however far we have advanced in overcoming prejudice, I doubt if we have yet got to a point where a British constituency would elect a black man.”

Naoroji lost at Holborn, but he won Finsbury Central for the Liberals six years later; Mancherjee Bhonaggree was elected in Bethnal Green North-East for the Conservatives in 1895 and Shapurji Saklatvala, Battersea North for Labour in 1922. All three, representing London seats, were from India’s Parsee community.

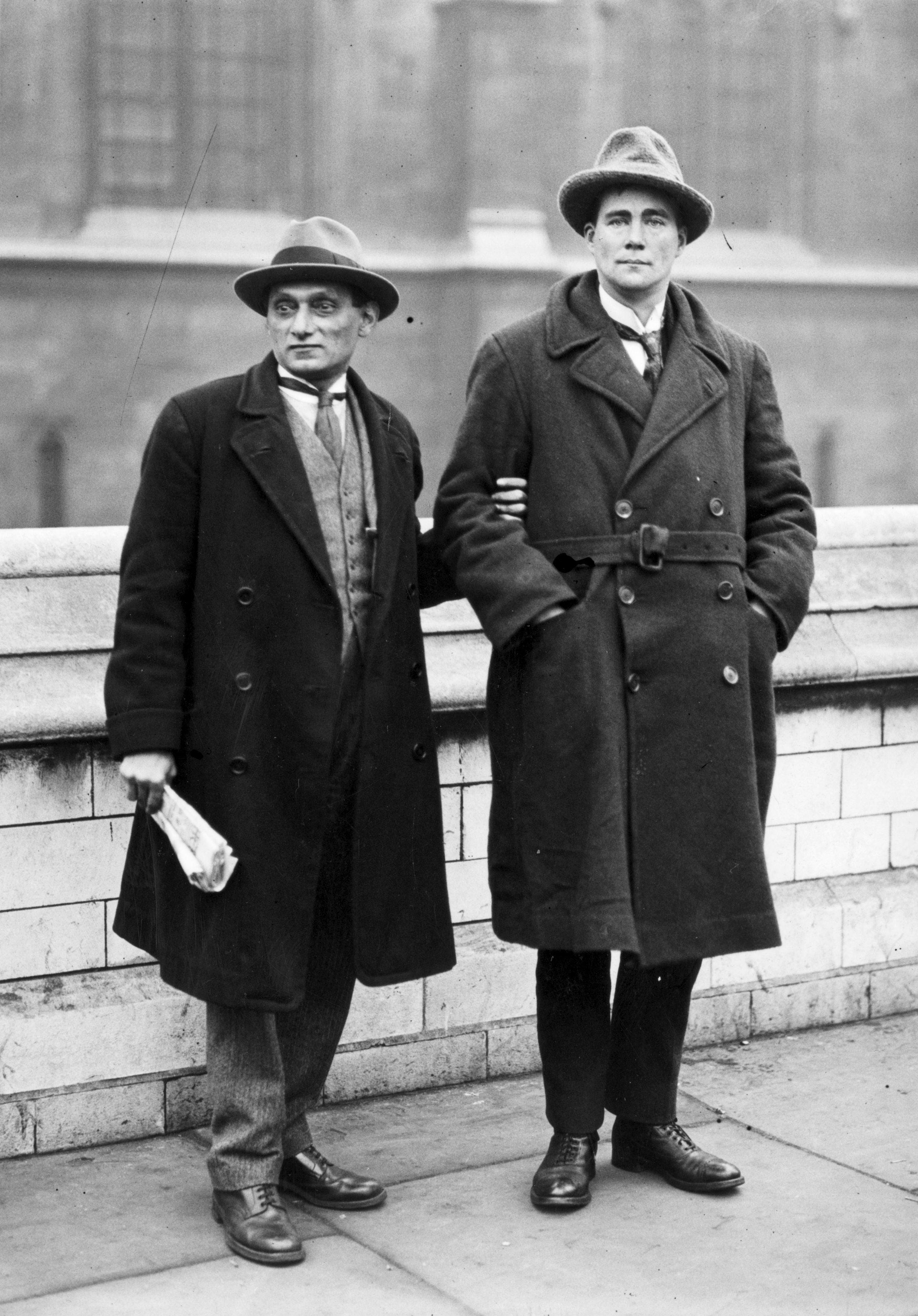

Saklatvala was the last MP from an ethnic minority background until the 1980s, and the highly interesting and turbulent life of Labour’s first non-white MP is the subject of an updated biography by journalist and political activist Marc Wadsworth, a founder member of the Anti-Racist Alliance and the Labour Party’s Black Section.

As well as charting Saklatvala’s life, Wadsworth seeks to draw a parallel between what happened then and the tensions and divisions in the Labour Party and left-wing politics today and the effect of propaganda.

Saklatvala had won Battersea North for Labour while facing an overtly racist campaign by his opponents. The book recounts Rajani Palme Dutt, a member of the Communist Party whose father was Indian, recalling the canvassing Tory candidate telling his Swedish mother Anne “of course, you’ll not want to vote for the black man”.

Anne Palme Dutt’s great-nephew, Olaf Palme, was to become prime minister of Sweden, a leading statesman of European social-democracy and a staunch opponent of South Africa’s apartheid. Palme’s assassination, in 1968, remains unsolved: there have been widespread claims that he was targeted by the South African regime.

Ramsay MacDonald’s government called a general election in 1924, but Britain’s first Labour government was heavily defeated with the red-scare of the forged Zinoviev Letter, printed in the Daily Mail four days before the election, playing a crucial part in driving away supporters.

The Letter purported to be instructions from Grigory Zinovivev, head of Communist International (Comintern) in Moscow, to the British Communist Party to engage in sedition, and it expressed satisfaction at the Labour government hastening radicalisation. The document was fake, manufactured, it is believed, by Tsarist Russian exiles, one of whom later went on to work for the Nazis, and an MI5 officer. Russia-linked interference in western elections and fake news did not start with Donald Trump.

Saklatvala’s radicalism led to police raids on his home and arrest and imprisonment during the General Strike for a speech appealing to soldiers not to open fire on workers

Saklatvala was a communist and the Labour Party had set on a policy of expelling communists before the election — a cleansing of supposed radical infiltration, which was to be replicated decades later with Militant and has echoes in the current friction between the party leadership and the Cobynistas and Momentum. Saklatvala stood again in his constituency as a communist and won, as Labour seats were falling elsewhere.

Saklatvala did not come from an impoverished background, something political opponents from right and left raised when criticising his radical pronouncements. He was born in Mumbai (then Bombay) in 1874. His father, Dorabji Saklatvala, was a wealthy merchant, and his mother, Jerbai, was a sister of Jamsetji Tata, who founded the Tata Group, now a global commercial and industrial conglomerate, already a powerful concern then.

Saklatvala, however, was not an heir to the Tata fortune. He worked as an iron and coal prospector for the company in India and moved to its offices in Manchester in 1905. He joined Lincoln’s Inn but left before qualifying as a barrister. He married Sarah Elizabeth Marsh, who he had met while she was working as a hotel waitress, in 1907. They had three sons, Dorab, Beram and Kaikhoshro, and two daughters: Dhunbar and Jevanbai.

Saklatvala was considered dangerous by the Conservative government, as declassified MI5 and police documents show. He intervened more than 500 times in his relatively short parliamentary career (calling the Speaker ‘comrade’ more than once) on the subject of India but also on a range of other issues, including social and industrial conditions in the UK, workers’ rights and Irish independence, often in terms cuttingly critical of the government.

Wadsworth holds that Saklatvala was primarily responsible for getting the left and liberals to focus on trying to end imperialism at a time when Labour luminaries such as Keir Hardie, Ramsay MacDonald and others returned from visits to India proposing reforms which sought to diffuse the “unrest” rather than lay a path to independence. The academic and writer Priyamvada Gopal views Saklatvala as a crucial figure in generating opposition to colonialism not just in India, but other parts of the world subjugated by the west in her incisive book, Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial Resistance and British Dissent.

Saklatvala’s radicalism led to police raids on his home and arrest and imprisonment during the General Strike for a speech appealing to soldiers not to open fire on workers. He was banned by the Conservative government from visiting India following a speaking tour of the country; the punitive measure was continued by Labour when it came to power. The US administration, with the urging of London, refused him entry.

Saklatvala lost his seat in 1929. He failed in two attempts to get back to the Commons but remained active in politics. He died in January 1936 at his home in Highgate, north London. His son Kaikhoshro served with the Air Transport Auxiliary in the Second World War, flying frontline aircraft including Spitfires and Lancasters.

Wadsworth, in Comrade SaK, has produced a thorough, well-researched and rich biography of a politician of colour who is little known, but played an important role in highlighting racism and imperialism at a time when such criticism was met with hostility and retribution by the establishment. Those continuing with the struggle for equality now owe a lot to the pioneering work of people like Shapurji Saklatvala.

Comrade Sak: Shapurji Saklatvala MP: A Political Biography, Peepal Tree Press, new edition 2020.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments