The Queen would never abdicate, but what about a regency for Charles?

A grateful nation might forgive the Queen if she decided to put her feet up at long last, as her late husband did, but everyone knows it’s out of the question, explains Sean O'Grady

The extreme longevity of Elizabeth II presents the country with the delicate question of how a monarch who is inevitably growing more frail can best deal with the duties of office, even if they are confined to the “light” sort. This applies most obviously to some constitutionally irrelevant ones, such as visits, and to those with greater significance, if only ceremonial, such as attending the Remembrance Day service, but also to those with modest political ramifications, such as advising her prime minister.

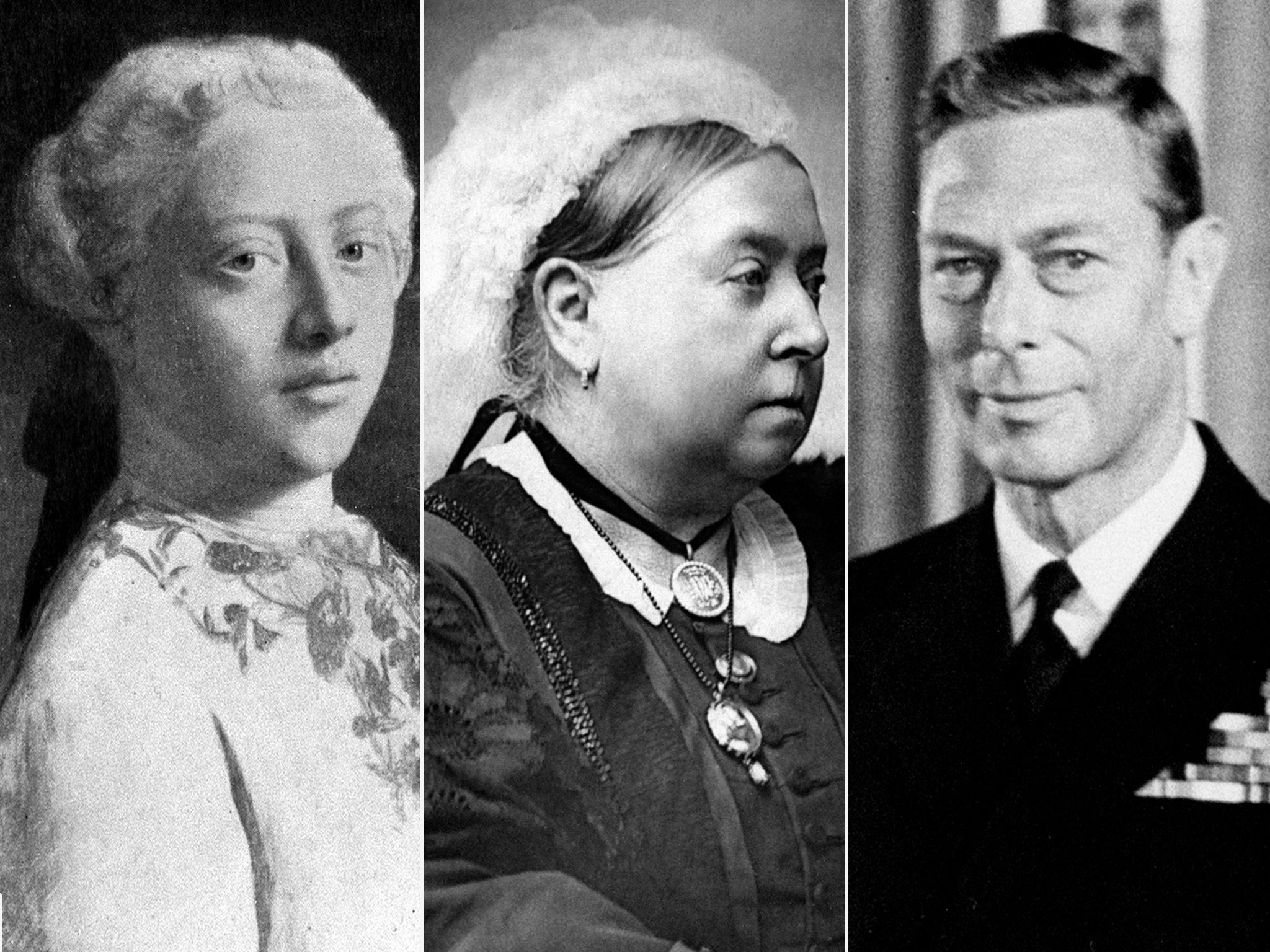

She is 95, and by far the longest-lived monarch in British history. Her father, a lifelong heavy smoker, died at the age of 56. Her great-grandfather and grandfather, also smokers, passed at 68 and 70 respectively, and Queen Victoria, who we think of as impossibly old, went to that great empire in the sky aged 81, just beating George III’s record. Victoria was old for her era, but would have been considered no great age these days.

In her way, Elizabeth II is a symbol of the greying of Britain. If she lives as long as her mother, in 2026 she will be one of the country’s 16,000 or so centenarians, who are mostly female and were part of a baby boom that came after the end of the First World War (though some of her contemporaries will have died before their time because of Covid). She’ll be able to send herself the famous telegram.

Such extreme old age, then, raises an especially delicate question, because the Queen is, so far as can be seen, as mentally sharp as ever, though physically not as active. She is not “incapacitated” and has even managed to get through Covid, albeit with missed engagements and little sign of her at the races or even at church.

However, there are mobility issues after her mysterious “bad back” incident last year, when the palace made the cardinal error of upsetting the press by covering up her spell in hospital (even flying the royal standard at Windsor to complete the unsuccessful subterfuge). Her most recent audience with Boris Johnson was over the phone, and ambassadors to the Court of St James’s present their credentials at a table next to a video link to the Queen.

It is some years, for example, since she went abroad, and most of her remaining “dominions beyond the seas” are now well out of reach. Such expeditions are now delegated to the heir to the throne, Charles, and his heir; William and Kate will be off for a tour of the Caribbean shortly. As the next Prince and Princess of Wales, they’ve just made their first St David’s Day visit to the country.

It must be in some doubt, for example, whether the Queen might be able to open a new session of parliament in the traditional manner. She has two major public appearances coming up, these being the Commonwealth Day service and the memorial service for Prince Philip, both at Westminster Abbey; and then a slimmed-down list of functions for her platinum jubilee, which would be tiring, to say the least, for anyone in their nineties.

A grateful nation might forgive the Queen if she decided to put her feet up at long last, as her late husband did, but everyone knows it’s out of the question. Or at least, abdication is, and you suspect that any courtier or member of the family who mentioned “the A-word” would be treated to a withering glare. She isn’t going to quit, because she’s made solemn declarations not to, and she famously takes her promises seriously, unlike some others in public life.

For the record, she said at her coming of age (21) on 21 April 1947: “I declare before you all that my whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong.”

As far as the Queen is concerned, abdication is not in the nature of the British monarchy, where it has been rare and, frankly, shameful

It’s dated, but it’s up there on the Buckingham Palace website, and it remains a personal pledge. Still more solemn were the coronation vows she took in 1953, at a serene religious service before God. Here is the official account of these sacred moments, in all their medieval, imperial and other-worldly glory, from the Order of Service:

The Archbishop standing before her shall administer the Coronation Oath, first asking the Queen,

Madam, is your Majesty willing to take the Oath?

And the Queen answering, I am willing.

The Archbishop shall minister these questions; and The Queen, having a book in her hands, shall answer each question as follows:

Archbishop. Will you solemnly promise and swear to govern the Peoples of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, Pakistan, and Ceylon, and of your Possessions and the other Territories to any of them belonging or pertaining, according to their respective laws and customs?

Queen. I solemnly promise so to do.

Archbishop. Will you to your power cause Law and Justice, in Mercy, to be executed in all your judgements?

Queen. I will.

Archbishop. Will you to the utmost of your power maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel? Will you to the utmost of your power maintain in the United Kingdom the Protestant Reformed Religion established by law? Will you maintain and preserve inviolably the settlement of the Church of England, and the doctrine, worship, discipline, and government thereof, as by law established in England? And will you preserve unto the Bishops and Clergy of England, and to the Churches there committed to their charge, all such rights and privileges, as by law do or shall appertain to them or any of them?

Queen. All this I promise to do.

Then the Queen arising out of her Chair, supported as before, the Sword of State being carried before her, shall go to the Altar, and make her solemn Oath in the sight of all the people to observe the premisses: laying her right hand upon the Holy Gospel in the great Bible (which was before carried in the procession and is now brought from the Altar by the Arch-bishop, and tendered to her as she kneels upon the steps), and saying these words:

The things which I have here before promised, I will perform and keep. So help me God.

Then the Queen shall kiss the Book and sign the Oath.

So, not something to be dropped lightly. As far as the Queen is concerned, abdication is not the nature of the British monarchy, where it has been rare and, frankly, shameful, though her uncle Edward VIII’s renunciation of the throne is how she became Queen.

Difficult as it may be to credit now, in the 1980s, in the heyday of the popularity of Charles and Diana, there was serious talk about pensioning off the Queen and letting the glamorous Prince and Princess of Wales take over. The Queen, perhaps knowing more about their private lives than the public did, remained unpersuaded and on the throne. Just as well.

Of course, the Queen doesn’t need to abdicate to allow other members of the family to take on patronages and military honorifics, and the Prince of Wales and others can bestow honours and accompany her at engagements, as has been the case since the Duke of Edinburgh retired from public life in 2017 (aged 96, as it happens).

But Prince Charles cannot legally, say, sign acts of parliament, appoint prime ministers or dissolve parliament, merely formal as these functions are. For that we would need the constitutional fix known as a regency – where all the powers and prerogatives of the monarch can be transferred to someone else.

So the Queen would still be Queen, as per the coronation oath, but Prince Charles would perform all her constitutional functions as Prince Regent.

Fortunately, most of the arrangements for a regency were prepared as far back as 1953, building on a template set in 1937, when the Queen’s father had become George VI and his heir presumptive, the then Princess Elizabeth, was 11.

Another option might be a ‘soft regency’, where the Prince of Wales takes on more of the Queen’s familiar duties, plus some, but not all, of the most important ones

A regency is thus ready to be implemented at any time, though it would be in rather different circumstances from those pertaining to the early part of the Queen’s reign. In the event of her passing, or other incapacitation, the crown couldn’t have passed to her children, because Prince Charles was five years old, and Princess Anne was three.

Even in a traditional country such as Britain, it would be difficult to justify having a toddler refuse to give the royal assent to bills passed by parliament, or to sack the prime minister – at the time Winston Churchill – because they were afraid of him. The age of infant monarchs, with or without “protectors”, had long since passed.

The surprising thing about the Regency Act 1953 is that it wasn’t the next in line to the throne – the queen’s younger sister, Princess Margaret – who would become regent, but Prince Philip: a rule that would apply until the children came of age (18). Perhaps it was plain sexism, or that the courtiers perceived some flaw in the fun-loving princess’s personality, but she was locked out of the role.

There were precedents. George V’s nominated regent was his wife, Queen Mary; and George II vetoed his son and heir from becoming regent because he didn’t like him.

In the decades since, the procedure has been refined and adjusted, and it now stipulates that certain named individuals, presumably on medical advice, must be “satisfied by evidence, which shall include the evidence of physicians, that the sovereign is by reason of infirmity of mind or body incapable for the time being of performing the royal functions, or that they are satisfied by evidence that the sovereign is for some definite cause not available for the performance of those functions, then ... as the case may be, those functions shall be performed in the name and on behalf of the sovereign by a regent”.

The individuals charged with this momentous decision are at least three of the following: the lord chancellor (effectively now the minister of justice, Dominic Raab); the speaker of the House of Commons (Sir Lindsay Hoyle); the lord chief justice of England and Wales (Lord Burnett of Maldon); and the master of the rolls (Sir Geoffrey Vos). Prince Charles would then become Prince Regent.

It would be a curious business: if it were being proposed because of the weight of public opinion – a feeling that the Queen was pushing herself too hard – and the Queen resisted, then it would be a rare example of the Queen defying public opinion.

The Prince Regent gave his name to an era, and left behind a fine architectural legacy, plus a personal reputation for defying his parents, meddling in politics, being unkind to his wife, and marrying his mistress

On the other hand, by its nature, the Regency Act doesn’t need the sovereign’s consent because that cannot be properly given. The last time a regency was set up was during the periodic madness of George III. In that case, the then Prince of Wales was made Prince Regent without the King’s assent to the relevant act of parliament, which had to be passed hurriedly and with little legal preparation. If nothing else, it was evident that even in those days of some monarchical power, the constitution was flexible enough and democratically driven enough to have the politicians making the key decisions.

The Prince Regent gave his name to an era, and left behind a fine architectural legacy, plus a personal reputation for defying his parents, meddling in politics, being unkind to his wife, and marrying his mistress. So nothing like the present Prince of Wales, and prospective next Prince Regent.

Another option might be a “soft regency”, where the Prince of Wales takes on more of the Queen’s familiar duties, plus some, but not all, of the most important (and less tiring) constitutional functions, until such time as she is no longer able to fulfil the rest. It would be a practical, pragmatic and respectful answer to a conundrum that can only become more pressing as time passes. The 1937 and 1953 acts could even be amended to “lose the bar” concerning “infirmity of mind or body incapable ... ”; the Queen could then formally grant her assent to the change.

One thing that would need to change, though, in order to gain political and popular consent for a regency of any shape, is the convention that the Commons never discusses the monarch, or at least avoids doing so.

You may recall a few weeks ago that Sir Keir Starmer mentioned the commonly made contrast between the conduct of the Queen at her husband’s funeral and the riotous parties in Downing Street the evening before. The speaker quickly shut the leader of the opposition up, in line with the usual practice of not discussing the Queen’s behaviour. But if the nation is to be ruled by Prince Charles as Prince Regent, it would seem only right to have such a proposal granted fresh democratic legitimacy.

The Abdication Act of 1936 was given a full Commons debate, complete with a full account by the prime minister of his dealings with the (soon-to-be-ex-) King. So the prohibition is not absolute, and it cannot be, where the constitution is affected. It ought to all go very smoothly. Provided she went along with it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments