There’s a lot more to having a quarter-life crisis than you might think

Ever had the urge to up sticks and move to a remote island off the coast of Nevercominghome? Sam Hancock finds out some bleak truths about quarter-life crises, from the people who know

A convertible car, a house in the south of France, a new haircut, a pair of designer trainers, or – heaven forbid – an affair: all common signs of a mid-life crisis. The idea tends to make us laugh, because stereotypically it means that someone isn’t coping too well with turning the big 5-0. But a relatively unexplored phenomenon is slowly entering public consciousness, encouraged by our increasing understanding of early adult brain development: the quarter-life crisis. Here, telltale signs are closer to uprooting your life to become a yoga instructor in Thailand, changing careers, trying drugs for the first time, or even joining a band.

Like a mid-life crisis, the quarter-life crisis signifies a pivotal moment in someone’s life when the idea of change becomes so overwhelming that emotions heighten and, in some cases, the person’s sense of rationale deteriorates – perhaps convincing them that a one-way ticket to India’s best-rated ashram is a completely sound purchase. The difference between the two is the age at which the crisis hits. Quarter-life crises affect those in their mid-twenties to early thirties, when, according to research, your brain is still desperately trying to figure out who it is that you are as a person – and ultimately what your place in the world is.

The term quarter-life crisis was coined in 2001 when authors Alexandra Robbins and Abby Wilner wrote a book of the same name. It wasn’t until 2010 though, says Oliver Robinson, an adult development psychologist and psychology lecturer at Greenwich University, that academics began associating the popular term with scientific research.

“I did my PhD in early adulthood crisis,” he recalls, “and then realised that it was already being talked about in the general public as a quarter-life crisis, so I bridged the two.” That led to a lot of media attention because there wasn’t much discussion about it then, says Robinson, especially among academics. “It wasn’t yet a well-known topic,” he says, “and to be honest, it still isn’t.”

A study by LinkedIn that surveyed more than 6,000 people found that 72 per cent of young Brits experienced a quarter-life crisis last year, while 40 per cent would say they are currently having one. It’s the “archetypal quarter-life crisis”, as Robinson calls it, that focuses on job dissatisfaction.

Over half of those surveyed listed not knowing what to do next in their careers as the reason for their crisis. Maria Arias was 24 years old when she quit her last job and made some big decisions that would come to define her professional and personal lives. A qualified lawyer and a key player in some of the world’s leading fashion brands, Arias says she never felt fulfilled in anything she did.

“I had these amazing jobs and felt completely empty. I never had the feeling I was doing anything personally profitable,” she says. “So, on the side of my job at Adidas, where I worked with Real Madrid FC, I began researching about the world, particularly the environment. I felt like if I couldn't be fulfilled professionally, I could at least try and live my life better.”

A year later Arias set up Madrid’s first ever zero-waste boutique, unPacked. The store sells environmentally friendly products and foods, and stocks no single-use plastics – including carrier bags. For Arias, it is also the place that changed her entire outlook on what it means to work. “For the first time, I can see my life going somewhere. In my last job, I couldn’t set myself any goals or objectives,” she says. “And they help you grow, both as a professional and as a person. They’re a motivator and I think that’s what I was lacking before. And what you do lack when you feel trapped in a job that you hate: motivation.”

Arias, now 26, is part of a millennial cohort often referred to as Generation Snowflake. The name, which was popularised in 2015 after a faculty-student showdown at Yale University in which students were accused of being overly emotional, is used to imply that twenty-somethings have become too delicate. Chloe Garland, founder of the life coaching service Quarter-Life, says the “common perception that a quarter-life crisis is simply entitled people whining” is completely untrue. “This issue has been around for decades, it’s just finally being given a name and starting to be dealt with,” she says. “I’d go as far as saying that a quarter-life crisis isn’t as new as it seems, it’s just that young people are now starting to want a sense of purpose much earlier than previous generations.”

This was certainly the case with Arias, who says she has “no doubt” that she made the choices she did because of how old she was. “Yes, it’s a young age to feel the way I felt, but also it’s an age when you’re trying to make something of yourself and you want to feel proud of that – not miserable,” she says. Fundamentally, she felt she had “no purpose” and it was this feeling that drove her to live “an unhappy life”.

Interestingly, purpose is one of the three “buzz words” that Garland says she hears most when meeting clients – the others are fulfilment and meaning, or lack thereof. “People tend to go through something like this when their sense of purpose doesn’t match up to the life they’re living, and the reason it’s so unique is because a mid-life crisis comes, supposedly, after a career when you’ve lived and understand your life better,” she says. “Whereas with a quarter-life crisis, you really are being thrown into a situation, probably for the first time, which is very hard to understand and can be quite scary.”

What is very possible is that people who are going through a quarter-life crisis will go and see their GP, or a counsellor, and be diagnosed with a mental health issue, if that individual meets the checklist criteria

Because the term quarter-life crisis was born and shared without any significant research to substantiate it, there remains work to be done to ensure that the seriousness of one is recognised. Robinson, who calls himself Captain Crisis due to his PhD studies, says that in the same way mental illnesses like depression are often referred to in frivolous ways, quarter-life crises can be blamed on, or mistaken for, an irritated mood or a bad day at work. “The only way to ensure it doesn’t become such a flippant term,” he says, “is for people like me to keep doing research.”

Robinson’s examination of quarter-life crises is particularly interesting due to his personal experience with them. When he was 26, working as a market research executive and in a “dead-end relationship”, Robinson says his life “fell apart” in the space of a year. “I was spending nearly all of my time trying to lead a very conventional life. I was aiming at conformist success and happiness,” he says. When the company that he had been working for closed down and he left his partner, Robinson says he was able to begin “exploring different sides” to himself. “I became more alternative,” he reflects, “it was like I’d been suppressing this part of myself for a while, it was very emotional and very difficult.”

After travelling to India to spend some time at a retreat, Robinson returned home and started a band, moved house, began writing a book and decided he would go back to university to study for his PhD. “It was a big turning point for me, I mean literally my life went in a completely new direction, through a very difficult period,” he says. “In retrospect, that was now what I would call a ‘locked-in crisis’, and it took the phase pattern that I now describe quarter-life crises as having.”

His affiliation with this field means Robinson is able to draw from his own crisis to inform his ongoing research – but is that a good thing, or is research more concrete when done objectively? “Sometimes you want to stand back and be objective, to get a distance from it,” he says. “But actually when you’re trying to understand something that hasn’t really been understood before, I think having that personal connection to it can be quite helpful.”

Crucially, work is not the only trigger for a quarter-life crisis. It’s essentially any transitional episode that a young adult experiences that typically lasts a year or so, during which time they are emotionally unstable. Anything from changing social groups to breaking up with a partner comes with an overriding sense of grief, Robinson says, which has to be dealt with in order for that person to move on.

Elyse Clark, a jewellery-maker from New York, was just 28 when she got divorced from her first husband; though it wasn’t the separation that sparked her downfall, it was her ailing marriage. “It was obviously a long time ago (Clark got married when she was 25, and is now 61), but even today, when you get divorced, you feel like you’ve failed. It was extremely upsetting,” she says. “And sadly, it’s not something you can go through without anybody knowing – when you’re married, everybody knows. So on top of your own issues, you have to deal with the embarrassment and what other people might think of you.”

I think when you’re unhappy, part of your unhappiness is coloured by an inability to look down the road and say, ‘The way I feel now is not how I’m always going to feel’. You think this feeling is going to last forever, but it doesn’t

Times have changed since Clark was in her twenties – they’ve improved, she says, because people are no longer pressured into getting married so young. Clark was married in 1983, and divorced three years later: “Back then, I definitely felt pressure from my parents – I think everyone did,” she says. “By the time I got married, people I knew were already having kids, which seems crazy now because we were all kids ourselves. I was only 25, but I remember feeling so grown up – now I don’t know if you ever properly grow up.” Clark’s sentiment seems to echo that of Mick Jagger’s, who famously once asked, “Don’t you think it’s sometimes wise not to grow up?”

What hasn’t changed, though, is the feeling of entrapment in a quarter-life crisis, which Clark says came to define her first marriage. “Before I moved out of the house me and my then-husband shared, every day I would think, ‘This is it, this is my life and I’m never going to be happy again’,” she recalls. “Now, that obviously seems so dramatic, but at the time it was perfectly reasonable – I was distraught and convinced that I couldn’t do anything about it.”

Clark says the weeks that followed walking out on her marriage – taking only her jewellery-making kit and pet cat – were some of the best of her life. “I think when you’re unhappy, part of your unhappiness is coloured by an inability to look down the road and say, ‘The way I feel now is not how I’m always going to feel’,” she says. “And that’s part of why you feel unhappy, because you think this feeling is going to last forever, and it doesn’t. It certainly didn’t for me.”

A structured crisis

To think that your quarter-life crisis won’t end, says Robinson, is a characteristic of their structure. “They have a narrative: a beginning, middle and an end. And it is the end that is particularly important to remember,” he says. People experiencing a quarter-life crisis suffer in part because they fail to recognise that their intensified emotions have a sell by date. “It transpires that it’s hard to know that you’re definitely having one at the time, but it’s very clear afterwards,” he says. “You may feel that you’re distressed, or think maybe this is some kind of mental illness. But actually, once you’re out the other side of it you think, ‘Oh, that was a process: I was relatively stable, then I fell apart for a short period of time and now it’s over.’”

Navigation is what ties Arias, Robinson and Clark’s experiences together – even though they endured very different quarter-life crises. Realising there would be an end was the hardest part for each of them, as well as figuring out what would happen next. “This is where more funding and research is pertinent,” says Robinson. “If people like me can work out why early adult crisis affects such a huge number of people, and what can be done to help someone more effectively – then we have a better chance of equipping people to deal with them.”

Worryingly, Robinson says, the lack of research and knowledge on the subject means people are at risk of mistaking this “developmental transition” with a mental illness. “What is very possible is that people who will be going through it will go and see their GP, or a counsellor, and be diagnosed with a mental health issue, if that individual meets the checklist criteria.” Doctors and therapists, he says, should be “empowered to understand” that in some situations the experiences of a young adult are not “indicative of an enduring mental illness, or some neurotransmitter imbalance”. Instead, he says, “sometimes people have to break down to break through; sometimes you need to disintegrate to reintegrate.”

Nobody can say what might have happened to a lot of incredibly famous people had the term quarter-life crisis been better known. But what can be agreed is that for too long early adulthood crisis has been underestimated and under-researched

Adult life inevitably brings with it a whole host of reasons to feel anxious, or lost, but what’s important is that young adults fight the tendency to become “creatures of habit”, Robinson says, to get overly complacent in any aspect of their life and to suppress their emotions to a dangerous degree. With this comes the need for the government and medical community to shine a light on quarter-life crises and make information about them more accessible.

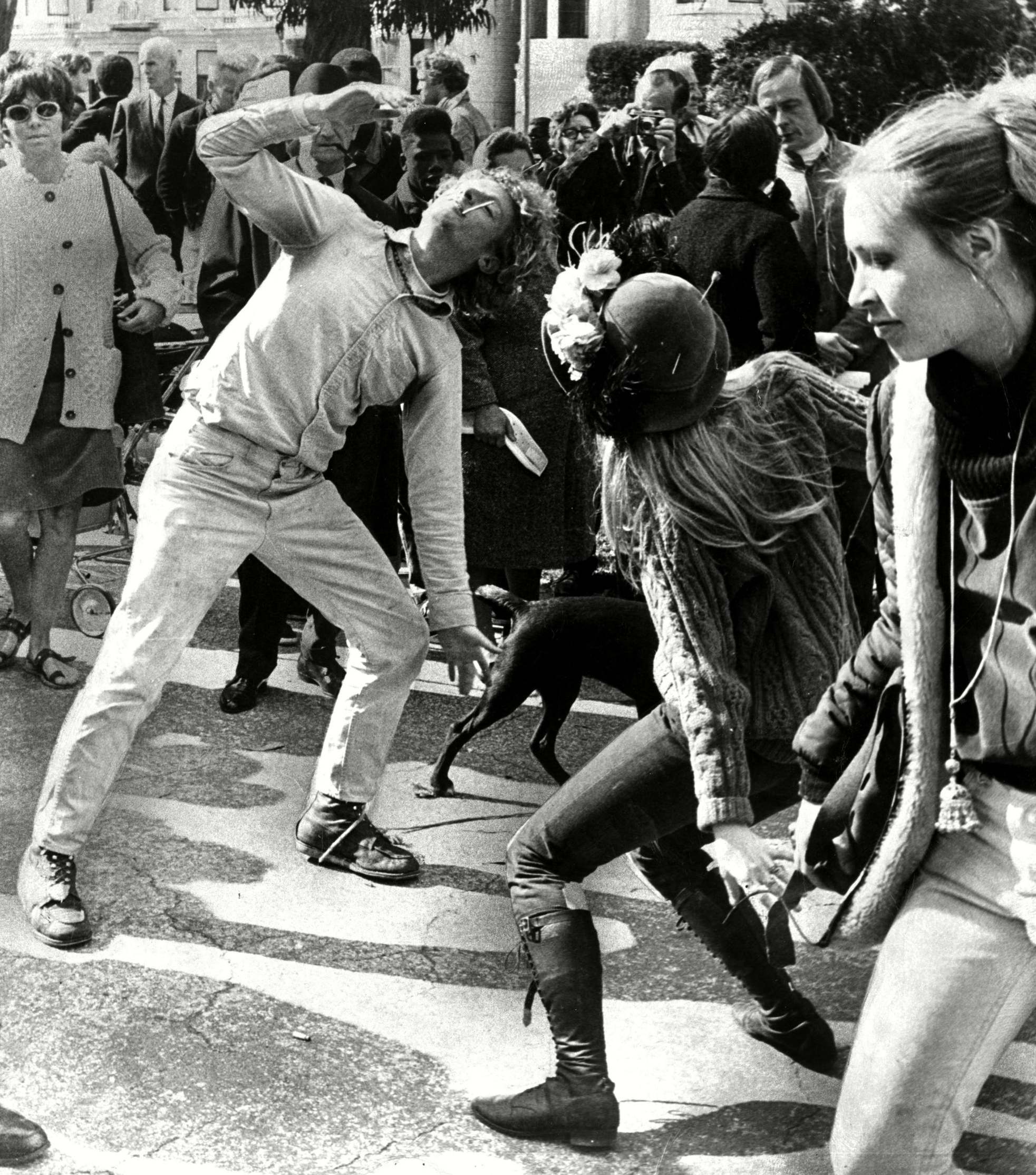

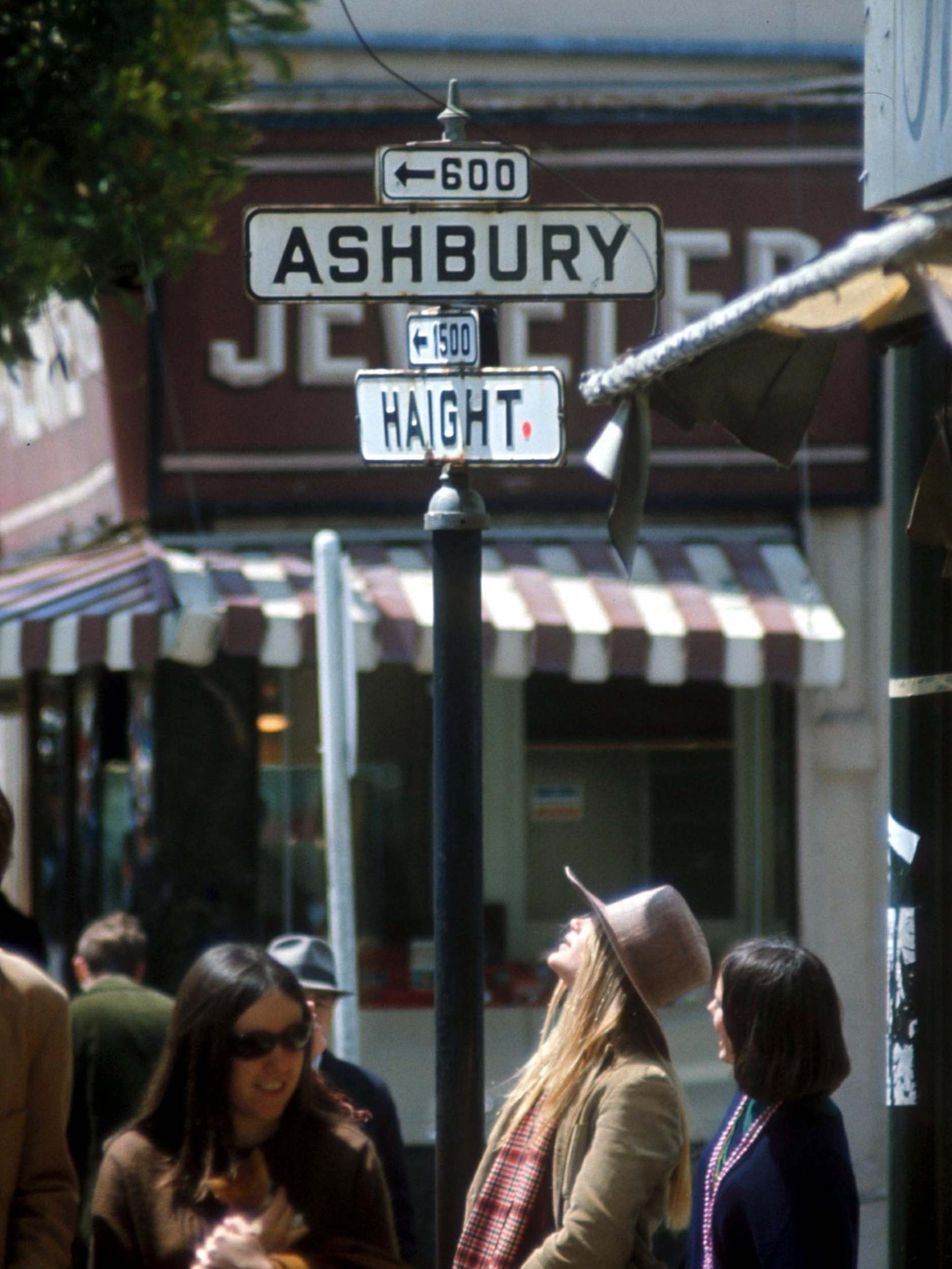

There are well known examples of what can happen when developmental issues are ignored: take the infamous 27 club, to which popstars Amy Winehouse, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin and Kurt Cobain are just a few of the celebrated members. Not to mention child actor Jonathan Brandis and famed graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. Even the infamous 1967 Summer of Love movement, which took place largely in San Francisco and saw young, impressionable “hippies” turn their backs on what they took to be an ailing society and instead chose to find solace in peace, love, flower headbands, meditation, music and drugs. Could they have been experiencing a kind of mass quarter-life crisis?

Nobody can say what might have happened to these people had the term quarter-life crisis been better known. But what can be agreed is that for too long early adulthood crisis has been underestimated and under-researched.

It comes down to what Robinson calls the basics: a person who is experiencing this should be able to access the necessary information to make an informed decision about what action they need to take. Should I go and see my GP? Do I need to call a helpline? Who is the best person for me to contact?

“These are all questions that don’t yet have an answer, and really should,” he says. “We need to help people make sense of this difficult episode they’re going through.” Whether that means an NHS “conditions” page, or greater media exposure on services such as Garland’s life coaching business Quarter-Life, he isn’t sure. “But what I do know,” he says, “is that something needs to give. Otherwise no one will ever be sure when they need to get help.”

Quarter-life crisis

The symptoms

A lack of purpose, meaning and fulfilment

Struggling with pressure from parents

A desire for autonomy – to not be a small cog in a large machine

Overwhelmed by every day life

Option paralysis – where there are too many options available, so you shut down

Striving, and normally failing, to achieve the holy grail of work-life balance

Social media provides a feeling of panic

Discontentment in any, or all, parts of life

Change isn’t always a bad thing

While the lack of funding and research into quarter-life crises is bleak, the experience of having one doesn’t necessarily have to be. What’s important, advises Robinson, “is openness. Don’t be afraid of change. In my experience, this is an opportunity to change, and I’d say embrace that opportunity.”

This advice resonates with me, because like Robinson, I have my own relationship with this issue. When my sister, Emma, began coming home from work in fits of tears and rage last year, I didn’t think too much of it. I assumed she was stressed and that, eventually, she’d get over it – that her bad days would become good ones again. We’d chat and I’d give her as useful advice as I could and for all our housemate and I knew, she was fine. She was just another person we knew who didn’t love their job.

When those bad days turned into weeks, then months and finally a year, though, it became clear that it wasn’t just her job that was getting her down, and that she was deeply unhappy in many aspects of her life. “I felt like I was drowning,” is how she sums it up now. “I was convinced that I was deeply depressed and my life was going to be that unhappy forever. Now I know that isn’t true, but I didn’t then.”

After turning 26, Emma decided enough was enough: she quit her job with no idea what she was doing next, was selected to run the London Marathon for a charity of her choice (and did so in a time of 4 hours 40 minutes), and began working for a company she believed in – and more importantly that believed in her.

So, I can safely say that Robinson’s not wrong: change isn’t always a bad thing. But ultimately, for people to know that – they also need to know what a quarter-life crisis is, and be confident in the knowledge that this issue is being treated as seriously as the latter part of its name suggests it should be.

If you think you’re experiencing a quarter-life crisis, you can get further information on Oliver Robinson’s website here. You can also contact Chloe Garland to arrange a free Quarter-Life consultation here, or arrange a cognitive behavioural therapy session via CBT Clinic London here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments